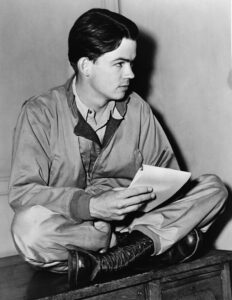

Cartoonist and writer Bill Mauldin. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-127496

The Oath Keepers, a militia group, is (still) in the news, as the Department of Justice and the House Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack on the United States Capitol continue their work on the scope and causes of that day’s events.

“Members of the group brought rifles to the Washington area ahead of January 6, when Congress met to formalize President Joe Biden’s election victory. Sixteen members and associates of the group face felony conspiracy charges linked to attempts to halt that day’s proceedings,” explains Mother Jones.

The Southern Poverty Law Center calls Oath Keepers “one of the largest radical antigovernment groups in the U.S. today. While it claims only to be defending the Constitution, the entire organization is based on a set of baseless conspiracy theories about the federal government working to destroy the liberties of Americans.”

The Oath Keepers (“Your Oath NEVER expires! It’s time to keep it!”) call themselves “a non-partisan association of current and formerly serving military, police, and first responders, who pledge to fulfill the oath all military and police take to ‘defend the Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic.’” No one asks them to take on this role.

One of the more interesting (and chilling) turns of this story was a recent leak of an Oath Keepers’ member spreadsheet, which gave self-submitted reasons for why 18,000 people had joined. Many never served in the military or were discharged involuntarily, were police officers (who are not meant to be soldiers), or had been radicalized by right-wing propaganda, and simply liked the idea of the paramilitary lifestyle.

“I think there’s a lot of people out there like that, who won’t qualify [for the military], but who really want to do it,” a former Oath Keeper told Mother Jones. “They’re going to go do it on their own.” He says the group “offers a way to serve…in the absence of other ‘boots on the ground fraternal organizations’ that might provide outlets to carry out a drive to be ‘guardians and warriors.’”

The magazine also quotes the author of a 2020 book on the group: “Some see it as a way to serve their country, which is part of what Oath Keepers recruit on…. For some, it’s a way to see friends. It can be like [my emphasis] a VFW Hall.”

To be clear, this idea to be “guardians and warriors,” while hanging out with friends, reserves for itself not just the right to assemble, to have an organized voice, or to protest lawfully, but also the right to use violence. Paramilitary groups may be “like” the military but lack the mandate, structure, discipline, training, and oversight of the actual military, and have no such right.

I was startled, recently, reading Bill Mauldin’s Back Home (1947), to see how many immediately post-WWII issues sounded as fresh as today’s news.

Mauldin famously cartooned the experience of WWII American grunts with his characters Willie and Joe; it was an experience he understood firsthand as a soldier in the 45th Infantry, during the invasion of Sicily and the fight up the peninsula, and later working for Stars and Stripes on the front in France, Germany, and elsewhere. After the war he became an editorial and political cartoonist—he earned two Pulitzers for his work—but he was always on the side of those without power.

Back Home is hugely sympathetic to the problems of returning veterans, such as racism, unemployment, a lack of housing, and predatory business practices. But Mauldin was also aware of anti-democratic forces within the notion of Americanism.

He says that most WWII vets had served in “a citizens’ army and its members wanted only to become citizens again,” but there were others “who make careers of convincing servicemen that one day or more spent in uniform entitles a man to devote the rest of his life to bragging about it and expecting special privileges because of it.”

A group called American Veterans Committee used the motto “Citizens first, veterans second” after the war, and while it had “no uniforms, no brass bands, and no baby grand pianos to throw out of windows,” Mauldin says, the AVC “jumped up to its neck in politics, on the theory that as a citizen the veteran should become active in affairs that affect the citizenry as a whole.” (There is an unrelated organization now with the same name.) The more liberal AVC was in competition with other fraternal groups that were conservative (and more successful), such as the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion.

The 1947 Legion National Commander admitted to Mauldin that the organization had been “conservative since the beginning…and that the Legion has maintained a constant hostility toward the left wing.”

Mauldin paints a picture of the Legion as reactionary, operating beyond the votes of its members, and “a maze of contradictions.” When Senator Robert Taft wrote a housing bill to help with veterans’ (and their families’) homelessness, the Legion “condemned [him] as a radical.”

“[I]n the case of housing, the organization placed its avowedly stanch belief in unlimited free enterprise above the thing so many veterans crave,” Mauldin says.

Yet the Legion, he adds, “knew that when a man is thoroughly bewildered and angry, it’s not hard to talk him into placing some of his troubles in the hands of those who promise to solve them for him.”

The Legion had a lobbyist, for example, who said, “Find out for me the attitude of your new congressman…. If you’re not sure about him, tell me and I’ll have a talk with him. If you hear from me after I see him, I expect you to put the fear of God in him.”

Mauldin admits that “in view of the fact that some unwholesome characters on the real lunatic fringe of American politics are making a great play to capture the valuable commodity known as the veteran’s mind, and turn it to their own ends, the young ex-warrior could be in worse hands [with the American Legion]…. But he could be in far better ones—his own.”

General Omar Bradley, who took over the dysfunctional Veterans Administration after the war, said, according to Mauldin, “Anyone, whether he be the spokesman of veterans or any other group of American citizens, is morally guilty of betrayal when he puts special interests before the welfare of this nation.”

Bradley spoke at the Legion’s National Convention in 1946 and said, “More dangerous than the German Army is the demagoguery that deceives the veterans today by promising him something for nothing.”

Mauldin admits, “Those who would make us a generation of professional veterans are not altogether villainous characters,” since many conservative policies are meant to better the nation’s financial health. But, “Demagogues have winning ways, especially with the man who has no one else to whom he can turn in his troubles.”

This idea can now be extended to those who call themselves “patriots” and does not even have to mean someone who served a single day in the service. One problem in our time is the addiction to the idea of military service, and a very narrow one at that. Google “Navy SEAL” and you will get 89 million hits, despite the fact that SEALs are less than one percent of US Navy personnel. Nobody wants to have been an Army diesel mechanic anymore.

The idea of what it means to serve now has been conflated with fantasies of violent paramilitarism, and the “troubles” that would-be patriots in camo hats and Oakley shades turn to demagogues for have been extended to all manner of reactionary gripes, but the dangers are the same ones Mauldin was writing about 75 years ago.