Matisse changed his mind, repeatedly. Infrared reflectography on exhibit at the Saint Louis Art Museum tells us so.

“With color,” Matisse once wrote, “one obtains an energy that seems to stem from witchcraft.” He knew how to cast the spells: when I close my eyes and see the Matisses I love best, it is those splashy but deliberate colors that bloom against my eyelids, lifting a humdrum mood into joy. There is not much joy elsewhere in these fractious days, so I beg Dr. John Klein, professor of art history and archaeology here at Wash.U. and the author of Matisse Portraits and Matisse and Decoration, to guide me through Matisse and the Sea, an exhibit up until May 12 at the Saint Louis Art Museum.

In the first gallery, I stand wordless, no clever questions, just soaking in the color. “See that arbitrary red beach?” Klein says, pointing. “He is more than representing something. He is expressing his response to the place.” Not inanely, I feel a red beach, or simplistically, I am happy today, let’s do red, but with a complexity and delight no emoji could carry. He was capturing what the French call sensation, the mingled response of the senses, the mood, and the heart.

Matisse sometimes squirted his paint straight from the tube, craving a clear, clean brightness and opacity. He never bothered developing a theory of color, though you could learn the color wheel from his triadic harmonies or his masterful balancing of salmon pink and ultramarine blue, pale yellow, and violet.

One of the throughlines in his work—which SLAM curator Simon Kelly captured comprehensively for perhaps the first time—was his love of water: swimming in it, rowing across it, and above all, painting it. Matisse described the water in Nice as “the color of sapphires, of the peacock’s wing, of an Alpine glacier, and the kingfisher, melted together, and yet it is like none of these.” Using strokes of ultramarine, turquoise, light blue, and sea green to show its endless variations, he painted rugged beaches on the Brittany coast; sun-sparkled waves in Corsica; the port in Collioure, a fishing village near the Spanish border; nude bathers in the French Riviera; stylized coral from Tahiti’s reefs. He even painted contained, domesticated water, sloshing in goldfish bowls and bathtubs.

His early work dabbed short Pointillist brush strokes to capture the waves’ movement, but by 1905, he was using broad swaths of color. Matisse was one of the Fauves, a surprising label that means “wild beasts.” Klein murmurs the backstory: at one of the Salon exhibits in Paris, an art critic saw a Renaissance-style bust of a child surrounded by bold new paintings, their colors freed from literalism and running wild—and wrote that it was like witnessing “Donatello chez les fauves.”

Klein, too, was gobsmacked by Matisse’s paintings in an exhibit, this one almost half a century ago in New York. “They knocked my socks off,” he recalls. “He is one of a handful of artists I would say are inexhaustible. There is no ultimate interpretation, no final word. His work is constantly renewing for each generation, like Shakespeare or Michelangelo.”

And just how do they manage that trick?

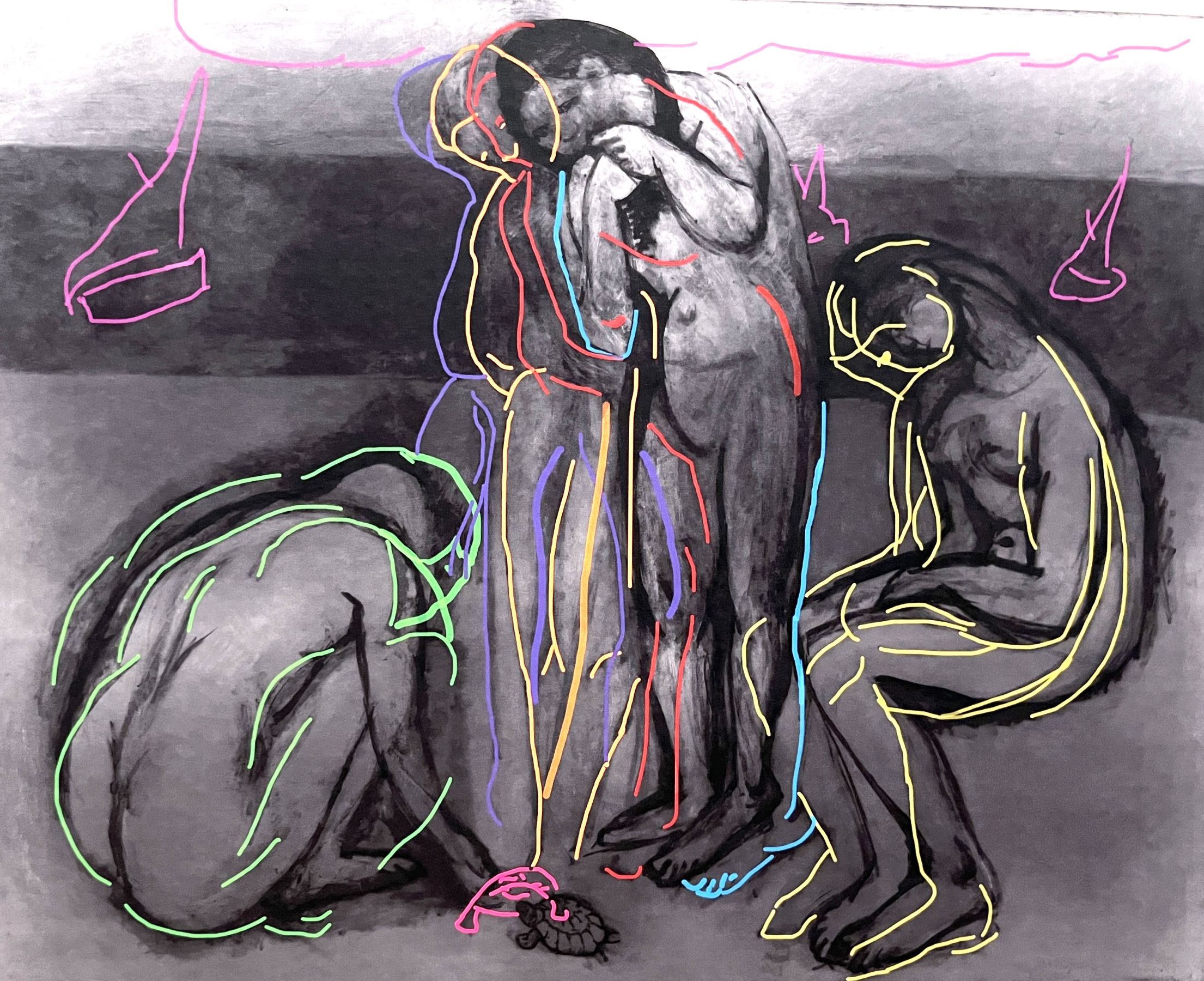

“It has to do with a tolerance for ambiguity,” Klein says. These are artists wily enough, surefooted enough, to leave their work open-ended rather than tying it up neatly. Matisse even lets us peek at the process, leaving signs of his revisions. In his masterpiece Bathers With a Turtle, infrared reflectography reveals a series of revisions, including the removal of sailboats, clouds, and hills to leave the painting placeless, available for anyone’s free association. When I puzzle over the gray shadow on the central figure’s face, Klein explains that it is “pentimenti, revisions that are visible on the surface. He was perfectly capable of covering them, but he preserved the evidence of his struggle. He’s not striving for finish. He’s expressing his path.”

As for the turtle, Klein thinks it is there to tease us. It serves as such a strong focal point that countless art historians have suggested fancy hidden messages, but Matisse was never one to bother much with symbolism. Except, to play with it. Klein is sure that “any educated viewer in 1908 would have understood that the painting refers obliquely to the Three Graces. Except these figures are not beautiful; they are ugly. It’s a refutation of the classical tradition.”

Matisse’s Bathers With a Turtle, at the Saint Louis Art Museum

Bathers With a Turtle was in a German museum collection when the Nazis seized it in 1938. Goebbels was savvy enough to know that this painting would bring hard currency on the marketplace. It was bought by Joseph Pulitzer, with Matisse’s son Pierre, a New York dealer, as his agent.

By then, Pierre was secretly busy helping Jewish artists escape from France. His father had refused to leave France, saying it would feel like deserting. So his wife volunteered her typing skills for the underground and paid with six months in prison. Pierre’s brother Jean was engaged in sabotage operations. Their sister joined the Resistance and was captured by the Gestapo; an Allied bombing made her escape possible.

Bathers With a Turtle, an acquisition that Pulitzer, a Jew, defended and later bequeathed to St. Louis, is the current exhibit’s showstopper. But I am drawn to the smaller, “lesser” works, the ones that make you happy you got up that morning. Matisse wanted his art to be “a soothing, calming influence on the mind,” and it remains so. He pursued “an art of balance, of purity and serenity devoid of troubling or depressing subject matter.” He paid attention to nature; he understood sensuous pleasure. He knew which colors we would thirst for, what decorative patterns would delight us. He played merrily with our perception, slanting floors and inserting aerial views. “One must always search for the desire of the line,” he told students; “where it wishes to enter, where to die away.”

Art critic Peter Schjeldahl once wrote that anyone who does not love Matisse’s work “must have a low opinion of joy.” They glow, sunlit and vibrant, which always made me think he was that rare creature, a cheerful and unflappable artist. But he tended toward depression, Klein tells me, and anxious self-doubt, and insomnia. Luckily, he had support: Gertrude Stein and her brothers; Russian and German collectors; two sisters from Baltimore who amassed a preeminent collection of Matisses. And his wife of forty-one years, to whom he was happily married “until he wasn’t,” Klein adds wryly.

Sadness, angst, and accusations of infidelity did not stop Matisse from working. Some of his early paintings were dark, sharp-edged, unappealing, but a lifelong goal soon emerged: to convey the beauty of the world to others who were suffering. The risks he took to do so sometimes backfired. Critics slammed him as shallow and decorative when his work was too pretty; students from the Art Institute of Chicago burned his Blue Nude in effigy, “charging” Matisse with “artistic murder, pictorial arson, artistic rapine, total degeneracy of color, criminal misuse of line, general aesthetic aberration, and contumacious abuse of title.”

To which the defendant replied, “Oh do tell the American people that I am a normal man; that I am a devoted husband and father, that I have three fine children, that I go to the theater!” Matisse offered no further defense; he once advised students, “If you want to be a painter, cut out your tongue.”

Though criticism stung him, he stayed open to the world. The exhibit includes sculptures from Guinea and other African countries that Matisse eagerly purchased, letting their stylized abstraction and altered planes and proportions influence his own work. A short stay in French Polynesia lingered in his imagination for decades: a string of Tahitian pearls adorns his Venus as she rises from the sea, and the seaweed fronds and coral branches patterning his famous papercuts. Both his giant Oceania works are in the exhibit (one owned by SLAM, the other on loan from Basel), and there are bird shapes in The Sea and fish shapes in The Sky, showing that in the liminal space of the lagoon, air and water meld.

“It has bothered me all my life that I do not paint like everybody else,” Matisse once said. Faux modesty? Or maybe he was bothered, on those nights he tossed sleepless, riddled with doubt. But in the morning, he always mustered fresh courage. Setting his worries aside, he tried once more to capture, for the rest of us, life’s joy.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.