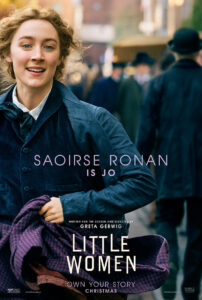

(Courtesy Sony Pictures)

When my bank asked for my favorite childhood book, I had to lie. Little Women seemed too obvious.

I read it in the tub, under the bedcovers, on my lap at dinner. I read it aloud to the dog. I snuck it outside when my grandmother told me to stop reading and get some fresh air. My mom was struggling alone, like Marmee, and I was an only child who craved the affectionate banter of sisters—not to mention the excitement of a boy next door. I reveled in all the creativity—the plays they put on, Jo’s writing, Amy’s sketches. And I loved the way everyone seemed fully themselves, known and (usually) loved for it.

The standard line is that Amy is selfish, Meg boringly maternal, Jo a tomboy, Beth a limp saint. But what I loved was that Amy could be frivolous and spoiled and her sisters would roll their eyes and rescue her from her latest disaster; that Beth could hide from the world and they would protect her; that Jo could storm about and defy convention and they would be proud of her regardless; that Meg could create a smug domestic world and they would alternately cherish its comfort and drag her out of it. How of ten d you meet siblings that functional?

In my twenties, I met a guy I knew would be a lifelong friend, and I told him that if he wanted to understand me, he had to at least skim Little Women. He reported back a few days later, made enough allusions to prove he had kept his word, then added dryly, “Well, you know it was written in 1947.”

My world froze. “Oh, no, it wasn’t. It was written in 1868.”

He shook his head. “Look at the endpapers. See how modern the graphics are?”

He was, of course, teasing. New edition, old book. But for just a minute, I was horrified. The book seemed so real to me, so authentic—a word we now desperately need because so much is not.

Reading more about Alcott’s life reassures me. “Never liked girls or knew many, except my sisters,” she wrote in her journal after her publisher asked her to write a girls’ book. She called the genre “moral pap for the young” and refused to write the expected stodgy prose. Instead, she used her life: Her sister Anna became Meg, Lizzie became Beth (and did die), and May became Amy. Marmee did not need to change—Alcott’s mother was already keenly aware of social inequality and injustice, and ready to give away even the little the family had to someone who needed it more. She was also a fierce if quiet feminist, and it is no wonder she asked that her journals be burned when she died.

The Alcotts’ years at Hillside, which were Louisa’s happiest, became the basis for much of the book. Where did she adjust and fictionalize? The sisters’ real lives held a far harsher poverty and the austerity of their father’s religious radicalism. So Louisa sends him away to war. The Alcotts moved often, which explains Louisa’s vivid conjuring of a cozy, stable home as refuge against life’s dangers. She captured her father’s dreamy idealism in Beth, and she used her own nursing experience in the war to anchor her fictional father’s heroic service. The March girls’ worry over their father’s safety in war becomes an analog for worry over a father whose enemy was inside his mind, and whose war was fought much closer to home.

I was crushed to learn that the real-life Meg lost her gentle husband soon after their children were born. I was delighted to find she had ambitions to be an actress and did not become engaged at twenty, but instead waited until she was twenty-nine. A bigger surprise: The real-life Amy did not marry until age thirty-seven, then died suddenly after the birth of her daughter the following year.

Camille Paglia called Little Women a horror story, and many a critic has lambasted the book (written a century before anyone thought this way) because the sisters end up either married or dead. But there, too, Alcott was ahead of her time. “Jo should have remained a literary spinster,” she wrote to a friend, and in another letter, “Publishers are very perverse & wont let authors have their way so my little women must grow up and be married off in a very stupid style.” Jo’s betrothal to the much-older Professor Bhaer was a mandatory concession. In the end, the joke was on Alcott’s publisher: The most universal criticism of Little Women by those who love the book is that Jo becomes so much less interesting once she marries. One’s friends often do.

Despite the coercion, Alcott made sure that the sisters do not yearn to marry or do so because they feel they must. Meg is eminently suited for the sort of domestic life we have all been resisting for decades now (and sometimes secretly desiring; just check Pinterest). Jo has to be dragged into vulnerability, and she winds up with a man who is more father than lover. Amy is startled to find that her childhood crush might actually be renewed and reciprocated. And only Beth dies, just as the real-life Lizzie did, both of them invalids without a clear diagnosis.

I am not alone in loving this book. In Jo, Beth, Amy: The Story of Little Women and Why it Still Matters, Anne Boyd Rioux includes a long list of women writers. “I was able to tell myself that I too was like her, and therefore it did not matter if society was cruel,” said Simone de Beauvoir. Gloria Steinem’s family moved so often that she longed for a home like the Marches’. J.K. Rowling finds it “hard to overstate what she meant to a small, plain girl called Jo, who had a hot temper and a burning ambition to be a writer.”

Nearly all of those women worshipped Jo, who, as the author’s alter ego, is given the best lines and the most obvious inner life. But I wanted a bit of each sister: Jo’s spirit and talent, Meg’s cozy nurturing, Amy’s sass and elegance, Beth’s spirituality. Each, like Hindu gods, carried some attribute I craved. And it is a cultural prejudice, I think, to write off Beth as insipid because she is shy and stays at home. Writing for National Public Radio in 2018, Linda Holmes says Beth “exists in the story largely to suffer and die, to represent the agonizing fragility of beauty and sweetness.” Yet she also represents the clear-sightedness of someone without ego; the ability of kindness to transcend fear; the close observation of the entire family that was possible because she lacked a private agenda to distract her. Beth’s world was small. Unless they leave behind a few canticles, like Hildegarde of Bingen, or tell the truth slant, as Emily Dickinson did, we dismiss such lives too easily.

G.K. Chesterton said that Little Women “anticipated realism by twenty or thirty years.” But this is an everyday, intimate realism that revolves around young women’s lives, so historically, many critics (first, male writers, then feminist scholars) have dismissed it as excessively emotional. I prefer the take of Greta Gerwig, who directed the just-released film adaptation (with Emma Watson, Saoirse Ronan, Eliza Scanlen and Florence Pugh playing the sisters. Gerwig describes the March sisters as “four really talented weirdo girls who were ambitious and funny and competitive and kind of crazy.”

Meg’s suitor, the gentle, doggedly unpretentious John Brooke, prepared me for my husband—who was just as clear when he warned me that all he was good at was history, and he would never make us tons of money. Meg herself readied me for domestic trials, Beth spurred me to overcome shyness, and Amy was the perfect caution against shallow aesthetic comparisons. Jo prepared me to work hard then have manuscripts rejected. Bhaer’s proposal, to a rain-soaked Jo who “looked far from lovely,” was as healthy a corrective to conventional romance as Shakespeare’s Sonnet 130 (“My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips’ red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun…”)

Little Women has never gone out of print. I wonder, though, what age the moviegoers will be for the new adaptation. Today, Jo’s remarks about wanting to be a boy and not wanting to grow up would raise questions of gender dysphoria. Meg would be dismissed as a soccer mom in the suburbs. Amy would be envisioned as Instagramming her life; Beth will be seen (perhaps rightly) as a candidate for psychiatric meds.

Rioux talked to quite a few girls who had started, but not finished, the book. “Nothing much seems to happen,” one said, and another complained that there was “no story. It just seems like real life.” These girls read dystopian, paranormal, and fantasy books in which heroines possess supernatural powers. Is that empowering? Is it feminist, to imply that normal abilities are insufficient and everyday life is unexciting? Instead of “I want to be a writer like Jo,” we have, “I want to be a warrior princess.”

Good luck with that.