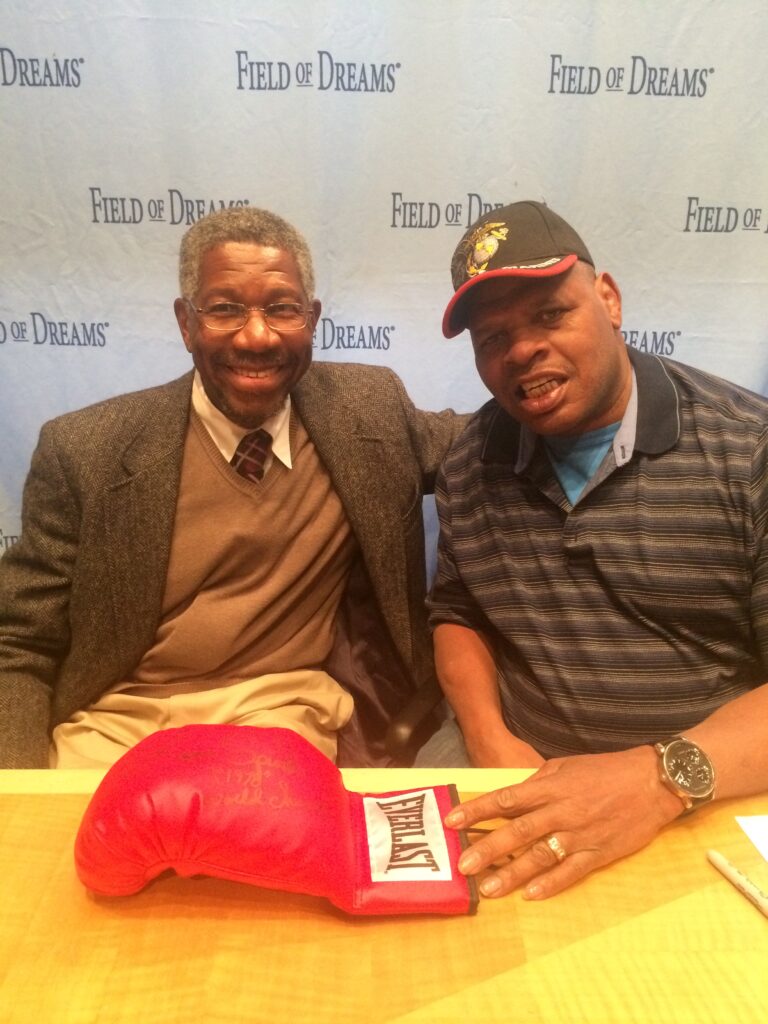

Professor Gerald Early with Leon Spinks at Field of Dreams, a sports and celebrity gift shop at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, January 2014.

On September 15, 1978, forty-three years ago on this day, Muhammad Ali, at the age of thirty-six, became the first heavyweight champion to win the title three times. This is a mixed distinction, as, while it may indicate tenacity and longevity to win a title three times, it also means Ali had the misfortune of losing the title three times. He beat a young ex-Marine named Leon Spinks, who had shocked the sports world by beating Ali in February of the same year by split decision. At the time Spinks won the title, he had had only seven professional fights. It is unusual for someone that raw, that much of a novice, to fight for a professional title, not simply because his handlers think him too inexperienced to fight a seasoned pro—which nearly all champion boxers are—but also because it is rare for a boxer in such an early stage of his career to have much of a name to make a title match financially worthwhile.

But Spinks was a name, hailing from St. Louis, growing up in Pruitt-Igoe; he and his brother, Michael, a better boxer who would become a more renowned champion, won gold medals in the 1976 Olympics, the same Olympics that produced the extraordinary Sugar Ray Leonard. Everyone remembered Spinks for his missing front teeth, his wild, undisciplined boxing style, his wide grin, his partying, his dim-witted charm. He was a bit like a Black urban version of The Beverly Hillbillies’ Jethro, a ghetto yokel. Sportswriters loved him for copy. This kind of back-handed acclaim, and his disinclination to have the rigors of becoming an elite boxer get in the way of having a good time, made it nearly impossible for him to have any hope of developing properly as a fighter. The publicity simply fed his indiscipline.

For Ali, who was completely bored with boxing and physically exhausted, the fact that Spinks was a name meant that a match between them would be financially viable, generating a nice, fat purse for Ali, who was fighting now strictly to support his huge entourage, pay alimony and child support, and to maintain his considerable fame and public adulation. A Spinks fight would not demand that the champ expend much effort. What chance would an undisciplined, technically deficient, inexperienced fighter have against the greatest boxer in the world, even if Ali was over-the-hill at this point. For Ali, this was a kind of Rocky moment. Giving some “famous-for-being-famous,” longshot loser and working-class hick, a crack at his title was, well, a magnanimous gesture. The whole thing was safe for Ali’s nervous system.

For Spinks, getting to fight Ali was as if he had just won the world’s biggest lottery. It was a Rocky moment for him as well, except he decided to skip the first movie and go straight to the sequel, where the longshot wins. Through sheer persistence, awkwardness, and aided by Ali’s undertraining and overconfidence, Spinks won the first fight. The second fight was different: Ali trained (a bit) and simply used his smarts, punching in flurries, holding and smoldering Spinks to prevent his attacks, much as he did Joe Frazier in their second fight. It was easier with Spinks because he was nowhere near as good as Frazier. Spinks had no answers for what the wily fox was doing to him. Spinks was easily captured by the tar baby, and lost the second fight decisively. It was not the end of Spinks’s career, although it might have been best if it had been. He even fought for titles again, losing every time. But for the six months that Spinks was heavyweight champion, he had a good time. He had once blown up the world. His nervous system could take it.

I met Spinks on January 10, 2014, at Field of Dreams, a sports and celebrity gift shop, in a mall in Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas. I cannot remember why I was in Las Vegas, only that I was there with my wife, my brother-in-law (who was in poor health), my sister-in-law, and my mother-in-law. I suppose it was a vacation of some sort. I have little memory of what I did most of the time I was there. I know that my wife’s family liked Las Vegas very much and that my brother-in-law had relatives there. Perhaps we were there to visit his family.

I went into Field of Dreams on a lark. There was nothing I wanted. To be honest, I only went in because the sign outside the store said that Leon Spinks would be arriving at 1 pm to sign autographs and talk with the customers. I had no idea before we happened upon the store that Spinks was going to be there. My wife realized my interest, even though I tried to act as though I was indifferent about Spinks’s appearance. My family indulged me as we had to wait nearly an hour for the event to start. They had no interest at all in Spinks. And there was no one else in line. I wanted to be first.

Spinks arrived on time, paunchier than I thought he would be, his face scarred and his eyes sleepy looking. He was loud and at times a little rude but on the whole pleasant enough. He shouted at my brother-in-law to join us as I sat at a table with him. My brother-in-law refused. I do not think he liked Spinks much. Spinks gave the overall impression to my in-laws of being a punch-drunk yokel. It was clear that his health had deteriorated since his days as an athlete. Over the last years of his life, he suffered a number of ailments, almost as if his body collapsed.

Spinks was pleased to know I was from St. Louis, his hometown. He asked me how things were there and in what part of the city I lived. We chatted for several minutes about nothing in particular, a little about his son’s boxing career. He signed stuff for me, and his agent took a bunch of pictures of us together. I had kept my wife and in-laws waiting long enough, so I took my leave after fifteen minutes. I could have stayed longer. In fact, as it turned out, I could have stayed the entire hour Spinks was there. I was the only person who showed up for the event. The world gets blown up so often these days that everyone has gotten used to it. Spinks’s nervous system was not what it used to be, and neither was anyone else’s.