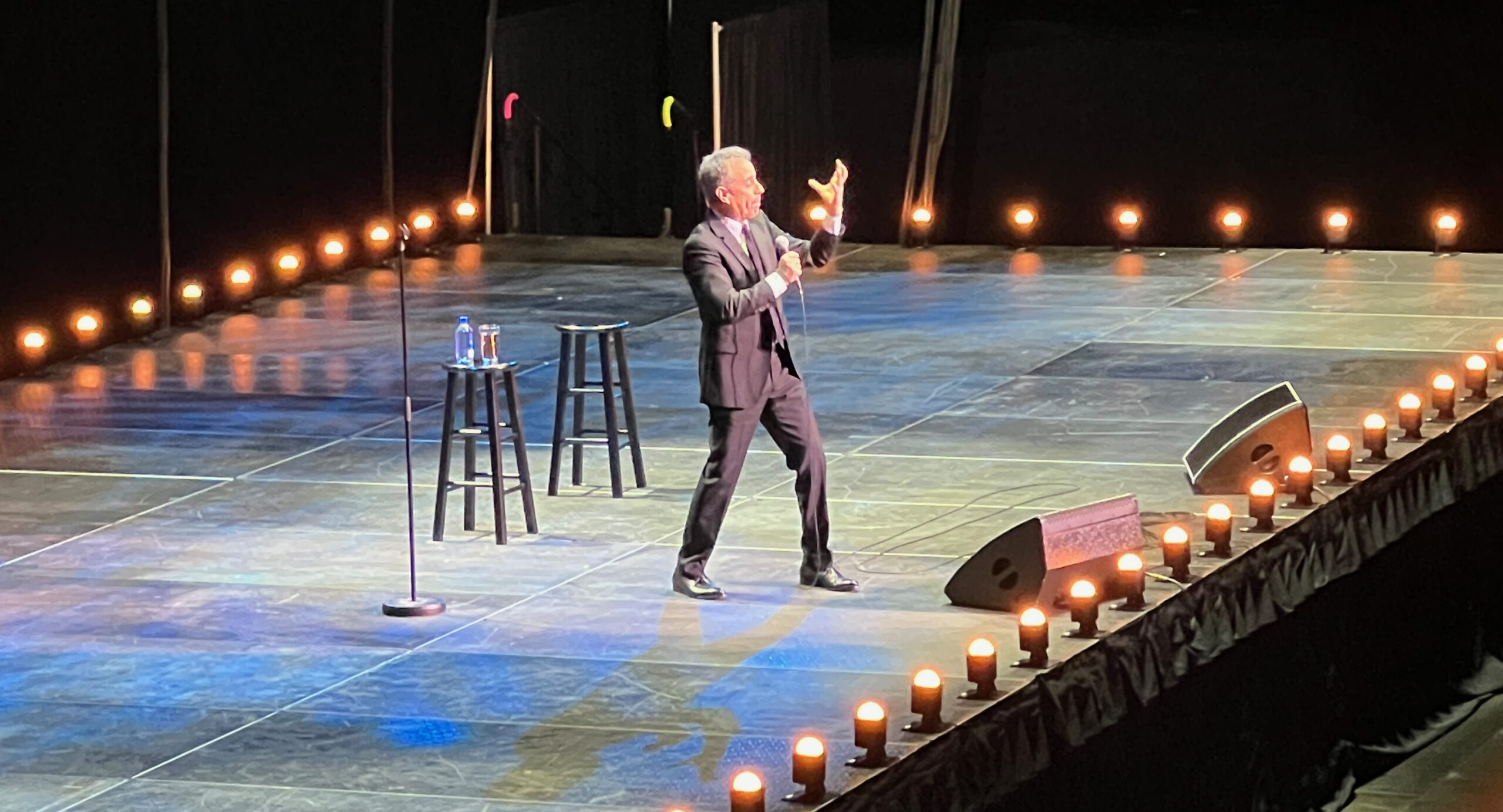

Jerry Seinfeld on stage, November 12, at the St. Louis Enterprise Center

According to Jerry Seinfeld, St. Louis is (sort of) his alpha and omega. He was in town for a standup concert last night at the Enterprise Center, an 18,000-seat venue where the St. Louis Blues play.

Seinfeld said when his sitcom “bombed” originally, appearing in a bad slot midweek after Unsolved Mysteries, St. Louis was the one market that kept it alive long enough to become a huge success. (Later in the act he said this was the sort of thing you tell an audience to make them feel good.)

St. Louis was also the final stop on his current standup tour, with Jim Gaffigan, after arena shows in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Chicago.

Mario Joyner opened for Gaffigan, who was followed by Seinfeld. If you, like me, feel you have not seen much of Joyner lately, it is because other than doing three episodes of Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee, he was last on a TV show in 2012, as a security guard on Big Time Rush, and had a role in a movie in 2011, Bucky Larson: Born to Be a Star. He is 62 years old, and a big part of his act is about aging.

The same went for the acts of Seinfeld (69) and Gaffigan (57). Gaffigan made the joke, “Does anyone else have email?” and another about how he thought an article about artificial intelligence was about a guy named Al. Seinfeld played the clueless husband in his own home, and told how he and his family went to the beach to swim but left because they got wet in the rain.

Perhaps by coincidence John Cleese (84) is in town next week for his show, “An Evening with the Late John Cleese.” (“In lieu of flowers, the comedian wishes for you to please buy the premium Meet & Greet tickets,” the venue’s site says.) Even Jerry Mathers (75) of “the Beaver” fame and Butch Patrick (Eddie Munster—70) did a charity event here last Friday. I would never purposely pay to see nostalgia acts or to hear comedians lament changing times, new technologies that are hard to figure, and aging bodies. That all ends in Andy Rooney (d. 2011) territory, and merely crotchety has never been interesting to me.

But avuncular Gaffigan, who I watched mostly for comfort in the pandemic because his persona is gentle and that of a dad to five kids, was edgier this time—“I’m dead inside,” he said and made a joke about murdering someone—a little political, and even mildly blue. “It’s like he’s become a real comedian,” a show-biz friend told me.

A big part of Seinfeld’s post-sitcom persona has been crotchety aging rich guy. In Comedians in Cars, he says he has no interest in talking to anyone but other comics and deems most pursuits “stupid.” Guest Alec Baldwin sets him up to make the joke that Seinfeld spends the day sitting on his back deck, answering the phone to say only, “No,” then hanging up.

I am interested in the existential component of these sorts of bits, how seeming loneliness in fame, wealth, power, and age, belie what the rest of us think we want.

In the first minutes of his most recent Netflix special, 23 Hours to Kill, in a bit about how we always want to be doing something else, Seinfeld says, “Nobody wants to be anywhere. Nobody likes anything. We’re cranky. We’re irritable. […] And so we come up with things like this [standup show], what we’re doing right now. This is a made-up, bogus, hyped-up, not-necessary special event.”

He does suggest in 23 Hours that he and we have known each other many years, electronically, “going through this life together, a beautiful thing,” then he purposely ruins it: “…I could be anywhere in the world right now. Now you be honest: If you were me, would you be up here hacking out another one of these?”

Well, there he was Saturday night in St. Louis, hacking out another one of those and killing it, as far as the crowd was concerned. When he first came out for his set, his voice was overwrought and angry-sounding, especially when he claimed to “hate everything.” But as in 23 Hours, the crotchety bit dropped away, and he spoke of his love of work and process. He did many of the observational comedy bits that are so “Jerry” (as fans call him) that they offer themselves imminently to parody: what is the deal with seedless watermelons, almond milk, five-hour energy drinks? And in terms of the observations of an older man, he built on previous bits about parenting differences among generations and made them more emotionally pointed. (“You know what my bedtime story was?” he said. “Darkness.”)

As for why he, Gaffigan, and Joyner were there, it turned out Seinfeld co-wrote, starred in, and directed a movie that will drop next year, and he really wanted us to know about it. The cast includes Gaffigan. That intelligence, coming late in Seinfeld’s set, felt like something cynical an older rich guy with endless opportunities in the entertainment biz might do as an accommodation to Netflix. That made me feel a little crotchety, but it was my first time seeing any of these comics live, and I had enjoyed the show.

The oddest moment in it, and the most impressive to me, was when I shifted my gaze from one of the Jumbotron screens where Seinfeld looked like a movie star—good lighting and excellent cameras projecting him as an enormous figure in control of the arena—to the stage itself, where an average-looking little man in a well-fitted but simple black suit and tie, as if in mourning, faced a strong light and spoke his mind, alone among thousands.