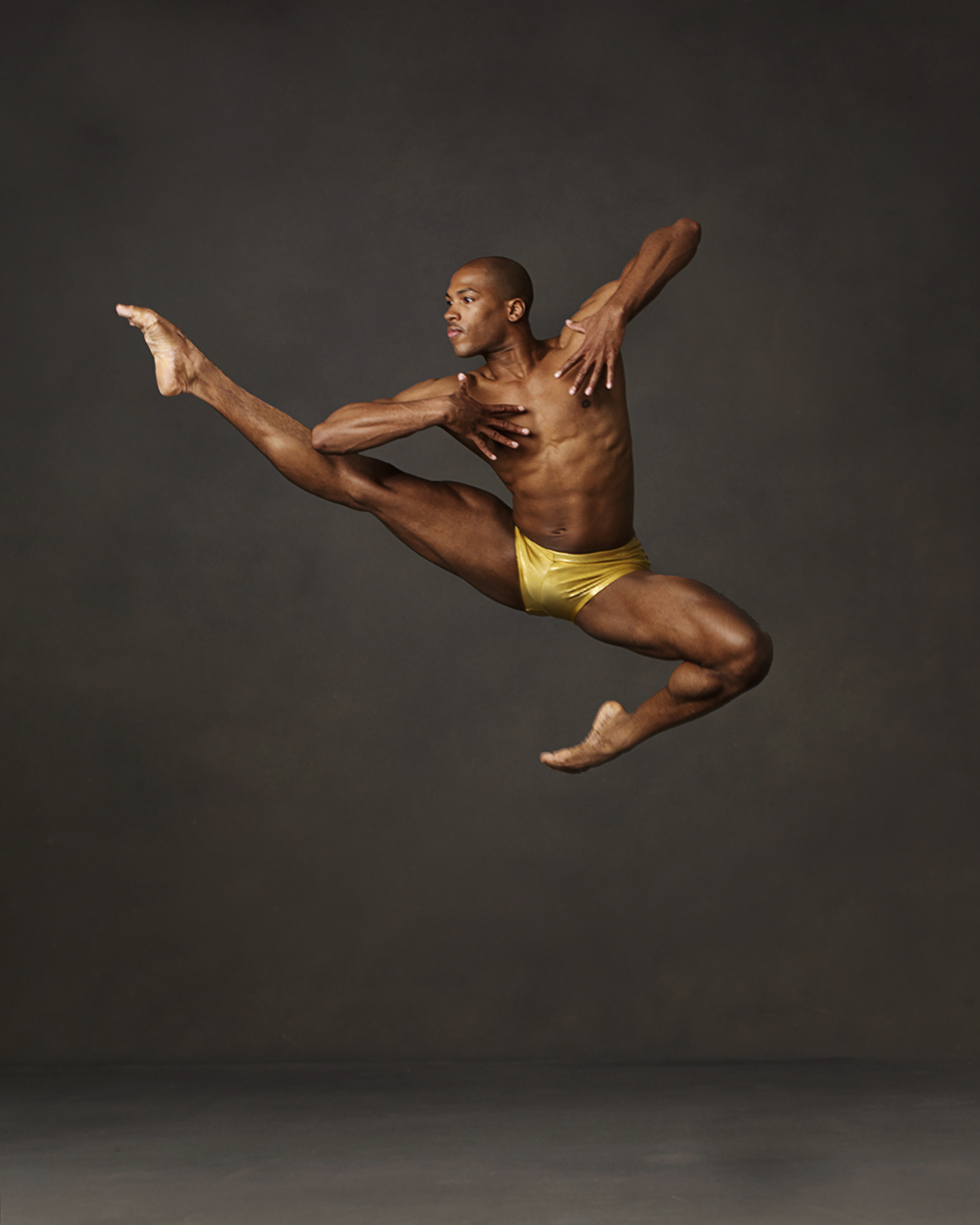

(Photo by Andrew Eccles)

Choreograph? Antonio Douthit-Boyd is a dancer. Trained at some of the finest ballet schools, including the Joffrey. A soloist in Arthur Mitchell’s Dance Theatre of Harlem. A principal artist for twelve years with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater. Praised in The New York Times as having “a special magnificence.” Eager, always, to put someone else’s vision into motion.

But now he is artistic director of dance at the Center for Creative Arts and professor of practice and ballet master here at Washington University, and he is beginning to have his own vision. It is tinged with self-doubt, though, so when David Marchant, a faculty colleague coordinating the student concert, asks if Antonio wants to choreograph for the next show, he says, “Nah, I’m a teacher.”

His husband, Kirven Douthit-Boyd—also a dancer, and a fantastic choreographer—waves aside Antonio’s fears. “Just put the steps together the way you put your class together,” he says.

O-kay then. First, he will have to find the right music, something he can fall in love with. Driving, he hears Al Jarreau’s scat-sung version of “Take Five.” The unusual 5/4 beat gives it a sexy urgency that Jarreau managed to capture without losing his cool, amused ease. “Oh, it’s short, sweet,” Antonio thinks. “I’ll get this over with in four minutes.” Could the students pull it off, switching to 5/4 and dancing by feel rather than counting eight beats on an internal metronome? “Take Five” is a small masterpiece: it will force them to break free, listen hard to the music, join the music. He begins to see the movements in his head, feeling how he would want to dance it….

The students come in hungry, impatient to know what he wants and already dedicated to giving it back. They stop him from second-guessing himself. What he has done with “Take Five” is good, he realizes, but it is too short. He needs something more. So he adds a Jarreau cover he has loved since he was five years old, “Ain’t No Sunshine.” The ideas are coming faster, spontaneous and free. You know, he explains, like the moves you make when you are dancing around your living room….

What I do dancing in my living room belongs on no stage. Antonio, though, has the entire vocabulary of ballet inside him. At Dance Theater of Harlem, Arthur Mitchell used to talk about how George Balanchine loved jazz, the speed and freedom of it, and how most of his movement vocabulary came from visits to the Cotton Club and other jazz haunts. Judith Jamison, another hero, “could come onstage and do the bare minimum and just control the stage.” Antonio wants his students to learn how to own themselves, own the stage.

Does that come from confidence or technique? Both, he says: “The confidence comes from being technically sound. A lot of people think you have to show the hard work. Technique is actually the opposite of that: maximum effect with minimum effort. You don’t want to beat the choreography up. You want the audience to think it’s beautiful and easy. Technical skill can give you command; you don’t have to prove yourself to anyone anymore. You are enough.” Some people work their way toward that confidence; others are born with it. “Beyoncé, no one had to teach her. She had that. Michael Jackson had that.”

He watches the students learn the piece, then urges them to “get a little more funky, that laidback jazz feel.” Perfect pirouettes, spine straight as a Greek column, must curve into something more sensuous and serpentine, the spine bending as they spin. When their legs come up and extend, he wants the gesture less controlled, more organic than geometric.

Kirven comes to one of the early rehearsals and whispers, “It’s great!”

Antonio is learning to think in patterns. He hunts for graceful ways to move dancers onstage and off, transition to a different group, or piece together a duet from two soloists who are dancing in extraordinary ways that just might fuse. Next time, he is already thinking, he will take more risks, do more with set design and props, use more of the dancers’ bodies, have them speak more.

So much would have come easier, he sees now, if he had known as a dancer what teaching and choreography have since taught him. “You break things down for young people to get them to understand where the movement is coming from,” he explains. “When I was dancing, there was no time to think about that process.”

Nor was there time to sympathize with the men and women who stood alone in the front of the room, “pouring out their soul to you, giving you the choreography that is in their head,” he adds. “It can be very lonely in the front of that room. You feel responsible not just for the piece being done but whether the dancers like it, and that can be daunting.”

He got lucky this time, he figures. They loved it.

So did the audience.

• • •

“I’m not interested in how people move but what moves them,” remarked the choreographer Pina Bausch. What first moved Douthit-Boyd was a drumbeat strong enough to rattle the air. It was coming from a studio on Washington Avenue. He and his friends, all early teens, crashed the dance class for the hell of it. The teacher, at first angry, registered their secret eagerness. Maybe she saw how Antonio’s body lit up with the music and longed to move. In any case, she said if they truly wanted to dance, they could come back the next day. Antonio, who was living in and out of shelters while his mom struggled with addiction, went back—again and again.

“It opened up possibilities,” he says now. “Before that, I was a good kid, an okay student, but I always felt alone. I felt like I didn’t fit into any one crowd. When I found dance, I found a tribe—people who were likeminded, who wanted to make art.”

Dance was the only thing in his short life that had ever made him feel special.

Now, he wonders why people grow up and stop dancing, frozen by embarrassment. One of his students, after catching sight of him off campus, said, “Mr. Antonio, I saw you skipping down the street!” Not unusual. “It just naturally happens,” he says. “A lot of people, if they would give in to that feeling and not think, ‘Oh, this is foolish’—” Little kids dance for the sheer fun of it, the freedom, he points out. “But when we are young, people put those pressures on us: what is good, what is bad, what is a boy, what is a girl.” Adults need to tap into the joy they felt before all that indoctrination, that fear of looking girlie or clumsy. As a choreographer, he wants to bring people back into that space, reconnect them with the ways their body wants to move.

“We all dance,” he says. “Your heartbeat is the rhythm. Just walking and being, everyone is dancing.”

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.