Washington University drama prof Elizabeth Hunter uses high tech to teach Greek tragedy.

How would your understanding of the religion’s immensity change if you could sit, tiny and quiet, in front of the crossed legs of a 233-foot Buddha sculpted fifteen hundred years ago? Would planetary science carry a little more intrigue if you could see, close up, what Mars looks like? Would Shakespeare’s role in the history of theatre pop a little brighter if you could feel yourself inside the Globe—in 1612, before the cannons in Henry VIII set fire to the thatched roof?

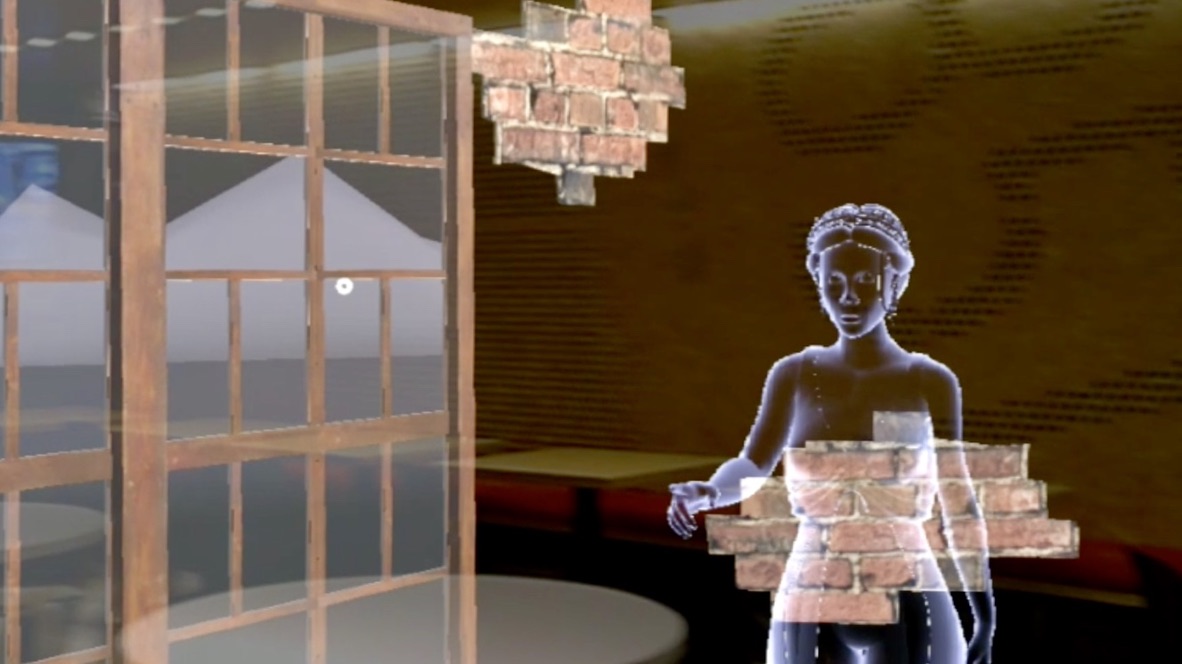

For centuries, the humanities have been taught with texts and lectures; art history with slideshows and lectures; the sciences with experiments and lectures. Then came VR and AR. And now, professors who have never felt the slightest desire to play a video game are downloading AR software, begging for I.T. help, and teaching their students—and themselves—how to construct worlds within worlds.

“There is this loose web of scholars at Wash.U. from different departments—art and architecture, romance languages, performing arts, earth and planetary sciences—and we are trying to figure out how to use VR for pedagogy and for research purposes,” Uluğ Kuzuoğlu, professor of history at Washington University, tells me over coffee. There is a delicious subversiveness to this, though it breaks no rule but tradition. They call their project IDEAS (Immersive Digital Experiences in Arts and Sciences). Their most sought-after member is Philip Skemer, director of the Fossett Laboratory for Virtual Planetary Exploration, which has the skills and software to explore three-dimensional data whether it comes from an atom or a planet. Because Skemer wants to see these resources used for the humanities as well as the sciences, the lab lends a hand. Art history students can peer inside a 3-D simulation of a 3,000-year-old vessel, pick it up, see what is inscribed on the bottom, sense more than they could if they flew to a museum on another continent.

For his class “Technology, Empire, and Science in China,” Kuzuoğlu brushed up on free VR software and then taught his students how to construct virtual museum exhibits. They found new ways to think about the spatial organization of knowledge, new questions to research, new ways to make the topics alive.

“I call myself an enthusiastic skeptic,” he tells me, admitting that he still has a historian’s reservations. You cannot get excited about this kind of tech without thinking about how it can invade privacy, manipulate desire, or deep-fake reality. On the other hand, this is the future; why not embrace its possibilities? There are, of course, the usual time-and-money limits: each project calls for different coding skills and software, and the tech instruction cannot eat into course time. By learning to integrate technological design with the critical thinking and cultural insights, though, students will be doubly literate—and thoroughly employable.

What if students come to take simulated, partial, inevitably flawed realities as gospel? Kuzuoğlu nods and rephrases: “How do you stop the tech from seeming to give people more knowledge than they really have? Part of it is to say what this is not; to open up a classroom discussion about what is missing. Right now I’m working on a reconstruction of Canton, now Guangzhou. Between 1757 and 1842, Canton was the only place where Western merchants could trade with Chinese merchants. And that was the only interface the Westerners had with the entire Chinese empire.” The emperor designated a strip of land along the coast for thirteen merchant houses. “We know what the front of the buildings looked like, but not the interior. So I’d be asking my students to research an interior for, say, a tea shop, and that would invite questions about what the research was and whether this is a legitimate way to think about a Chinese tea shop.”

He can send students into the simulated Canton to hunt for a particular place; they can ask larger questions about how the place was run, how it can be animated, how it was lit, what the roads were like. There could be a photo exhibit in one of the buildings, historic texts, footnotes, a virtual Wikipedia. “And then next year a student will do something completely different, maybe research an exhibit on opium smoking.

“It’s easy to fall into the trap of taking it literally,” he concedes. “‘Oh, this is Canton.’ No, it’s not. But you put so much effort into creating it that it becomes hard to say it’s not real. That’s what we should be avoiding. This is meant to enhance critical thinking. We’re not trying to create a game we’re gonna sell for forty bucks on PlayStation 4.”

What is this new technology adding, Kuzuoğlu keeps asking himself. “What are the intellectual questions we can grapple with in this medium?” Either it will just turn out to be a fun new teaching tool, or it will open up a whole new world of inquiry, and the suspense is killing him.

I surprise my romantic, nineteenth-century, Luddite self by hotly defending this foray. Meta’s aspirational metaverse feel icky, crass, and psychologically dangerous, but this? This is what happens when the same technology is used to understand the world, not manipulate its denizens into forking over their cash and their identity. If you ever envied Dr. Who his ability to shoot through space and time and blink awake in a new lifeworld, you cannot help but be intrigued.

For years I have fretted that all this simulated reality will deaden our powers of imagination. Why, for example, would I want to step into a simulation of somebody else’s idea of 124, the house in Beloved, when, thanks to Toni Morrison’s gift, I already know exactly what I think it looks like? When literature lets you form a mental picture that vivid, other people’s visuals are nearly always a disappointment. We do not need tech to replace our imagination, just set fire to it. And there are VR and AR projects that will let us sense, question, wonder, and analyze in entirely new ways.

Why the difference? Because there is nothing passive about these simulations. Students collaborate to create these experiences, or they explore them with purpose—and in so doing, they find out how many tiny nitty-gritty facts they have to hunt down and how startlingly relevant the smallest detail is. Suddenly it is urgent to know what building materials were used—and oh, there was a shortage? For economic and political reasons? Questions keep unfurling.

Next, Kuzuoğlu might shift from VR to AR. He teaches a class, for example, on “Asia in St. Louis.” Rather than a simulation, why not augment the existing reality? “How cool would it be to have a little QR code outside Brookings Hall, so you could scan it with your phone and see the Chinese Pavilion that once stood in its place? And maybe a 3-D reconstruction of the pavilion itself. . . . ” He can also imagine AR changing perceptions of North St. Louis.

How ironic, and folk-tale perfect, that a technology that frees us from space and time would have the richest and most interesting applications locally.

He nods. “As information technologies make us more disembodied, we are searching for more embodied experiences. We don’t want to lose our bodies! We don’t want to have classes in Metaverse!

“Metaverse still seems gamey,” he adds. “This is an alternative way to think about these technologies. If we had the power Facebook has, what kind of alternative world would we create, as scholars?”

One aimed at insight, not gimmickry, and created carefully, to deepen knowledge, not recklessly, for profit.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.