“At exactly fifteen minutes past eight in the morning, on August 6, 1945, Japanese time, at the moment when the atomic bomb flashed above Hiroshima, Miss Toshiko Sasaki, a clerk in the personnel department of the East Asia Tin Works, had just sat down at her place in the plant office and was turning her head to speak to the girl at the next desk.”

So begins John Hersey’s Hiroshima, a book particularly powerful in its time for its unusual form, which combined the calm voice of an omniscient narrator in fiction with the researched experiences of people who had witnessed unspeakable violence. The book is every bit as powerful still, on the 75th anniversary of the world’s first atomic bombing of a city, for its straight gaze at horror. Some 220,000 people died at Hiroshima and at Nagasaki, which was bombed three days later.

The world is dangerously unstable, again. In January, The Science and Security Board of the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists moved their Doomsday Clock to 100 seconds to midnight, its most “dire” warning of impending annihilation and extinction—even more perceived threat than at the height of the Cold War. This is, in part, due to world leaders who “denigrate and discard the most effective methods for addressing complex threats—international agreements with strong verification regimes—in favor of their own narrow interests and domestic political gain.” President Trump has disavowed or pulled out of the Iran nuclear agreement, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, and the Open Skies Treaty, all of which help keep nuclear warfare from developing.

Two days ago, when the port at Beirut exploded, I thought it must have been a tactical nuclear weapon. The veterans on the combat engineer pages I frequent were warning each other not to try to be experts, because none had seen a blast like it. It turned out to be ammonium nitrate, a common fertilizer and conventional explosive used as a low-brisance “heaving” charge by construction firms and terrorists alike. But the 1995 Oklahoma City blast was two tons; Beirut was 270,000 tons.

And that is part of the impact of Hersey’s book. We think we know; we turn our heads to say something; the impossible happens outside the window. As I wrote here last year, during a visit to Hiroshima, the city is now bustling and modern. It is little different from any other, if you were looking for some difference due to its history, but that is perhaps its true warning to the world as a “City of Peace.” The bombing was only 75 years ago, no time at all, and our common humanity is still always one bright flash from extinction.

Below are several photos from Hiroshima at the 74th anniversary. My thanks to WUSTL’s Newman Exploration Center and Travel Fund for their generosity.

Hiroshima, July 2019, from the Hotel Intergate.

Trolley driver’s point of view.

A friend and I under the hypocenter, where temperatures reached 11,000 degrees.

The ‘Genbaku’ or A-Bomb Dome, also under the hypocenter, and one of the few buildings to survive.

Shukkeien Park, which features prominently in Hersey’s book as a refuge for the wounded and dying. He knew it as Asano Park.

In the Peace Memorial Museum. The trike belonged to the little boy, Shinichi Tetsutani, who died from the blast, as did his sister.

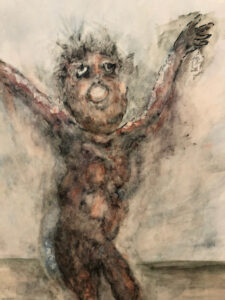

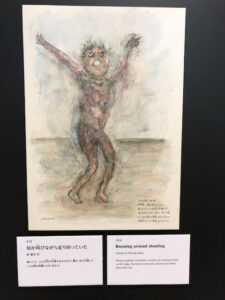

Artwork, titled “Running around shouting,” by survivor Hiroshi Hara.