Hire Vitrivius to Do Your Interior Design

August 28, 2025

Imagine yourself in ancient Rome, visiting a pal’s marble-slicked townhouse. You will either step directly into the airy, skylit atrium or walk down a narrow hallway to reach it. You will then wait in the atrium for the paterfamilias, because there are rules of decorum as well as decor. In How to Make a Home: An Ancient Guide to Style and Comfort, Vitruvius et alia hold forth on domestic architecture with the savoir-faire of a modern shelter magazine—echoing many of today’s precepts and provoking doubt about the rest.

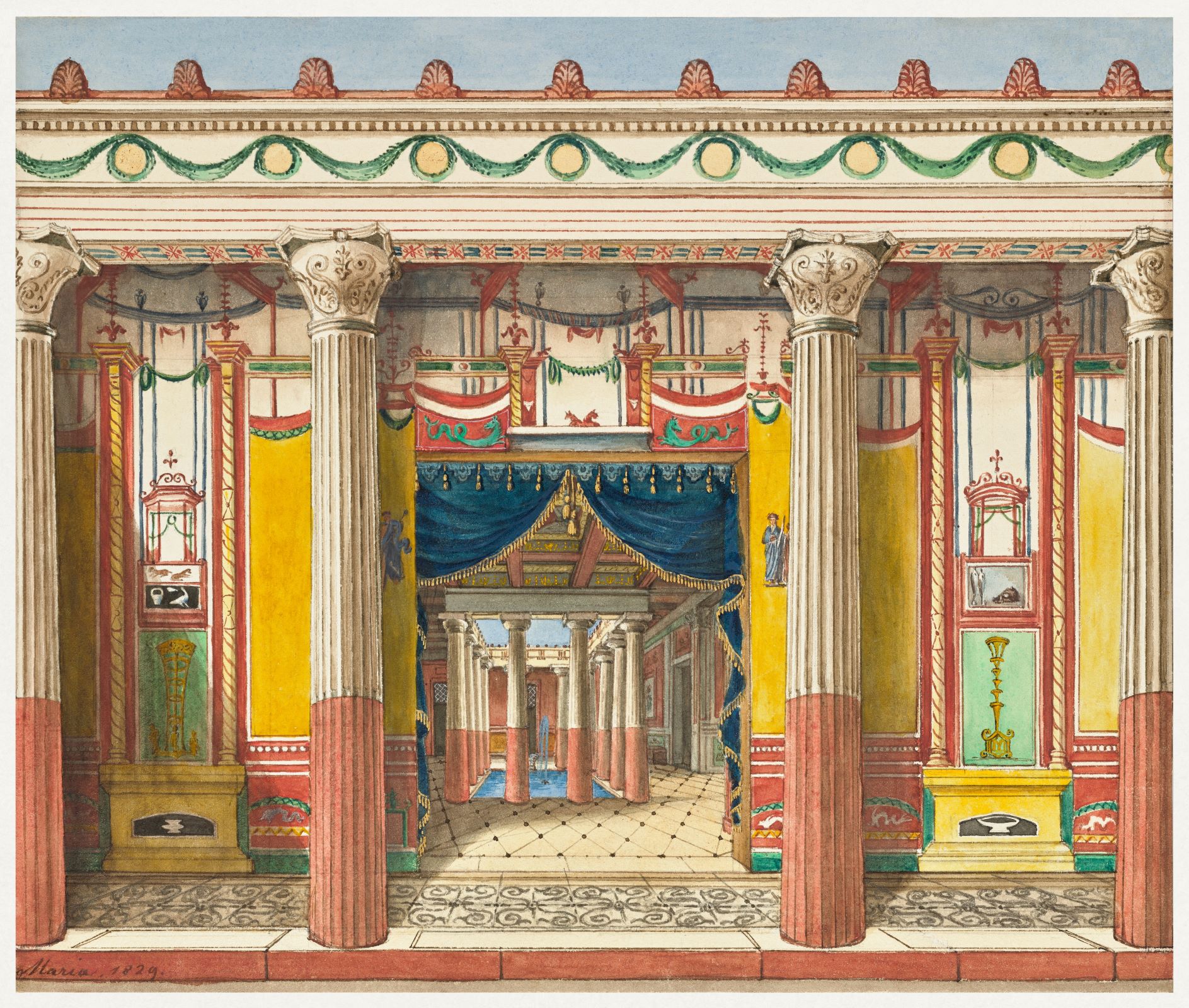

In the townhouses they consider, the rooms are often laid out back to back, centered on an axis in order to allow a sightline deep into the house. Privacy is often a matter of indifference: those with means want their home to be not only seen but accessible to all sorts of visitors, proof of its owner’s openness. This is as political as it is hospitable, suggesting what today we call “transparency.” When the tribune Marcus Livius Drusus was having a house built on the Palatine, his architect guaranteed that he would design it so that it would be “free from scrutiny, protected from all onlookers.” Drusus must have raised an eyebrow. “Really now,” he said, “if you have the talent, build my house so that whatever I do can be scrutinized by everyone.”

Perhaps your friend has left the townhouse, though, for her family’s country villa. There, nature plays a larger role, with open courtyards and long, shaded colonnades. Those who can afford to experiment use these villas as a canvas: Emperor Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli laces sculptures of Egyptian crocodiles alongside a water feature pretending to be a canal off the Nile, a less than subtle reminder of the vastness of the Empire. Other villas play with topiary, gazebos, shrines, and trompe ’l’oeuil murals that bring the garden indoors. The shelter magazines thought they had invented that idea?

After we learn about atria, Vitrivius goes to the other extreme, praising the cozy interior hearth. Humans were first terrified of forest fires, he writes, then startled to realize “that the heat of the fire was a great comfort to their bodies.” He credits this discovery for bringing people together, encouraging their capacity for deliberation, and gathering them into denser living arrangements. Some “began to make dwellings from foliage, others to dig caverns under the hills, and still others, imitating the nests of swallows and their construction methods, made shelters from mud and sticks.” Homes became steadily more sophisticated, better at solving the problems of existing comfortably in a nature that insisted on raining, freezing, blasting heat, and blowing on them.

The Greek author Strabo applauds the Romans for their civil engineering (plumbing, sewage, roadworks) but bemoans their unsustainable home construction, flammable and easily toppled, as they built higher and higher “in defiance of structural capacity and good sense.” Strabo is especially aggrieved by teardowns and real estate flippers: “The re-sales, undertaken by people tearing down and building up one house after another, to suit their whim, are akin to voluntary collapses,” he writes. Such silliness is possible only because of nature’s ample supply of building materials, but even in the first century of the Common Era, Strabo sounds worried.

Cicero chimes in (that man has a way of winding up everywhere). Here, he sets standards for the sort of house “a respected and distinguished person should have.” A pragmatic house, he insists, useful above all else, though “careful attention must be paid to its proportion and stateliness.” No gaudy McMansions would pass his test, but “at a prominent person’s house, where many guests must be received and crowds of all kinds of other people admitted, there should be a great concern for spaciousness.” Absent regular entertaining, though, you have what is most common in our own mansions: dead space. We think vast estates glamorous, but in Cicero’s opinion, “an enormous house is often a discredit to the owner, if there is an emptiness about the place.”

I think of all the contemporary homes I have visited in order to write about their breathtaking architecture and sumptuous interior design. Nearly always, they have been sterile, seamless, and empty, with fancy kitchens that look like no one ever boils spaghetti in them. In a home that is too grand, too big, too concerned with providing luxurious amenities no one will ever fully use, the inhabitants rattle about. The homes are so lifeless and lonely, you end up feeling almost sorry for them.

Juvenal pokes fun at another practice of the wealthy: “What good does it do, Ponticus, to be admired for a distant bloodline, to put on display painted portraits of your ancestors…if one lives badly.” Juvenal also disses urban life, preferring the countryside and small towns on the coast. “After all,” he writes, “what place have you ever seen that is so depressing and desolate that you wouldn’t consider it worse to live in fear of fires, and the continual collapsing of buildings, and the thousand other dangers of the cruel city of Rome… The place to live is somewhere without fires, or anxieties for one’s safety at night. “

How many news reports I have seen of house fires in North City, families barely rescued or children burned to death. How little changes, in cruel cities.

Having made his point, Juvenal lightens into crankiness, railing against loosened roof tiles that smash down upon the pavement: “You can be considered irresponsible and oblivious to the possibility of accidents if you go out to dinner without having made your will.”

And with that, we return to Cicero, who is not a tease so much as a provocateur. “Let’s say a respected man is selling a house because of certain flaws, which he himself knows, but which other people know nothing about. Let’s say it harbors disease, but is considered hygienic, and that the evidence of maggots in all the bedrooms is not well known….” Such dilemmas, with mold substituted for maggots and hauntings or murders for disease, still trouble those of us with scruples. Cicero asks his colleagues if refraining from disclosure is unfair, and the first says yes, absolutely. Diogenes, true to form, disagrees. “Someone who didn’t even encourage you hardly forced you to buy it, did he? He posted an advertisement for something he did not like; you bought something you did.… Whenever there’s a buyer’s discretion, how can there be seller’s fraud?” In other words, keep your mouth shut, and caveat emptor. Because “in all honesty, what’s stupider than a seller describing the flaws of the very thing that he sells? And furthermore, what would be as preposterous as an auctioneer announcing, at an owner’s bidding: ‘I am promoting the sale of a disease-ridden house’?”

The next time we buy a house, I hope the sellers have not read Diogenes. And that they have read Vitruvius. You know how contemporary interior designers advise “bold use of color”? He criticizes earlier generations for using vermilion “sparingly, as if they were taking medicine.” Vermilion, malachite green, purple, and Armenian ultramarine—these colors, even if they are not applied skillfully, “render a gleaming appearance.” A far happier prospect than a pale, neglected house, which Plautus compares to a neglected soul. Tiles break, rain streams through the gaps, beams rot, and “the integrity of the house becomes compromised.” This, he says, “is not the builder’s fault. Instead, the majority of people have adopted this habit: if anything costs money to be repaired, they wait around and don’t do it.” We call this deferred maintenance, and who among us has not deferred some pesky and pricey repair?

On a field trip to the villa of the famous general and war hero Scipio Africanus, Seneca turns nostalgic, realizing how simply Scipio lived and how plainly, in a dark cramped room, he bathed: “He stood beneath this roof, which is so humble; this floor, which is so ordinary, bore his weight. But who is there now who could bear to bathe that way? A person considers himself poor and lowly unless his walls shine brightly with large and expensive discs of precious stone.” Or, today, unless his shower room is so vast that he will have duckybumps unless he carefully regulates his thermostatic shower system’s rainwater showerhead body jets.

The best décor porn comes from Pliny the Younger, who writes of his own country villa’s dining room, projecting toward the seashore and “lightly lapped by the spray from the bursting white caps. All around, it has either folding doors or windows the size of doors, so that from the sides and front it affords views that create the impression of three seas.” Set back from this room is a smaller room “that lets in the rising sun through one window and holds onto the setting sun through the other.” Adjacent is “a secluded nook, which retains and intensifies the direct sunlight, and then “a private room curved into an arc, which follows the course of the sun through each window. A bookcase is built into the wall.” In the adjoining bedroom, a raised floor and piped walls distribute captured air of the perfect temperature. Then there are the plunge baths, the massage room, the sauna, the heated swimming pool, the turrets, the wine cellar, the private terraces.

No one has ever found this house; it could well have been a fantasy. We all dream of the perfect place to live, then sigh over the shoddy or gauche options we face instead. Reading this book, one wonders why, in twenty-one centuries, we have not learned more.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.