Grumpy Old…Men?

July 3, 2025

Friends have typical bucket lists—climbing Everest, running the Boston Marathon, seeing Venice before it sinks—but my future recently cleared, distilling itself into a single aim. I want to become a curmudgeon. A blazing act of defiance, this. Cleveland Amory once noted that “being a curmudgeon was the last thing in the world that a man can be that a woman cannot be.” It is time to seize the role.

Some years have passed, after all, since Amory made his pronouncement—though not nearly as many as have passed since the word was first coined, in 1577. Century after century, the role of curmudgeon has been cast for a male past sixty, a grumbly old guy, once formidable, who now stands on the sidelines muttering.

Often he is funny. Ambrose Bierce listed four kinds of homicide: “felonious, excusable, justifiable, and praiseworthy.” Quentin Crisp said crisply, “To know all is not to forgive all. It is to despise everybody.” Oscar Wilde defended “what people call insincerity” as “simply a method by which we can multiply our personalities.” Adlai Stevenson said “a lie is an abomination unto the Lord and a very present help in trouble.”

Dorothy Parker is just as wry, just as transgressive. But no matter how cynical a woman becomes, she cannot make it all the way to grumpy. We come right to the edge and get branded bitter, shrewish, cranky, bitchy, or mean, instead. Bossypants, never grumpypants. Which I suspect is because we are always being measured against the cuddly nurturing assigned to our sex.

But curmudgeons grow people up, too.

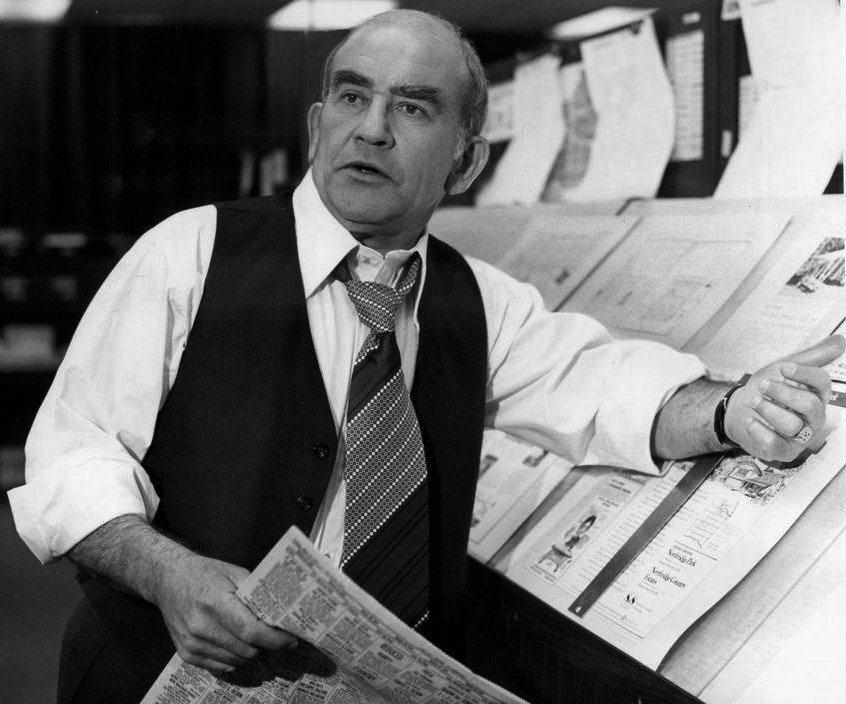

Lou Grant, shirtsleeves rolled up, scowling across his desk at Mary Tyler Moore. Abe Vigoda as Fish on Barney Miller; Redd Foxx as Fred Sanford, Hugh Laurie as Dr. Gregory House. Samuel Johnson, John Adams, even the man called Ove. I loved those guys. Too much sweetness, too much palaver and perky optimism and influencer smarm, and you need an antidote. Grumpiness is honest, and there is often wisdom beneath its crust. I regularly pull out Montaigne as a yardstick: “Nothing is so firmly believed as that which we least know.” Samuel Johnson stopped me cold by observing, “He who makes a beast of himself gets rid of the pain of being a man.” Thomas Szasz stopped me, too, when he defined happiness as “an imaginary condition, formerly attributed by the living to the dead, now usually attributed by adults to children, and by children to adults.” H.L. Mencken presaged Trump’s sales of golden sneakers with the weary aphorism: “Nobody ever went broke underestimating the taste of the American public.” And Voltaire left us an even sharper lesson: “To succeed in claiming the multitude you must seem to wear the same fetters.”

Politics is a curmudgeon’s favorite playground. In his Devil’s Dictionary, Bierce defined political life as “a strife of interests masquerading as a contest of principles. The conduct of public affairs for private advantage.” He defined “alliance,” in international politics, as “the union of two thieves who have their hands so deeply inserted into each other’s pocket that they cannot safely plunder a third.” He defined history as “an account, mostly false, of events, mostly unimportant, which are brought about by rulers, mostly knaves, and soldiers, mostly fools.”

Curmudgeons, you see, have standards. Sherlock Holmes could not abide being fooled, and Statler and Waldorf suffered no foolish puppets. Mark Twain rolled his eyes at idiocy of all sorts, and Lewis Black skewers it. “Curmudgeon” once implied that you were a “surly, ill-mannered, bad-tempered fellow,” which certainly explains why women could not qualify, as none of those adjectives are sanctioned for us. But environmentalist Edward Abbey noted in self-defense that the label’s meaning had evolved “to refer to anyone who hates hypocrisy, cant, sham, dogmatic ideologies, the pretenses and evasions of euphemism, and has the nerve to point out unpleasant facts and takes the trouble to impale these sins on the skewer of humor and roast them over the fires of empiric fact, common sense, and native intelligence. In this nation of bleating sheep and braying jackasses, it then becomes an honor to be labeled curmudgeon.”

Who would not want to seize that role? In preparation, I have charted many possible paths, a taxonomy of curmudgeonry. My husband, who finds cheeriness nearly intolerable, chose the Eeyore route. He joins poor Max Perkins, the legendary literary editor who once sighed, “Every good thing that comes is accompanied by trouble.” But Andrew prefers to cite the Ferengi Rule of Acquisition No. 285: “No good deed ever goes unpunished.”

Beneath his resigned pessimism, though, Andrew is also another sort of curmudgeon: the cynic who is secretly disappointed that the world is not all it could be. Failed idealism never ceases to grieve and exasperate. “You shall know the truth,” Aldous Huxley wrote, “and the truth shall make you mad.”

Then there are the perfectionists, more exacting than idealistic, and annoyed that so few of us meet their criteria. They forget their own lack, which is the tolerance for frustration necessary in any civilized society. Bierce was confessing his own temperament when he defined patience as “a minor form of despair, disguised as a virtue.” No, not “confessing”—there is an unmistakable note of pride. Yet for others, the real exasperation is often with the self, as when Samuel Johnson admitted, “I hate mankind, for I think myself one of the best of them, and I know how bad I am.”

Some old guys, though, are grumpy in a teddy-bear way. Once fierce, they are now Rudolph’s Bumble, toothless and softened by age, finally able to let their heart speak but still mortified at the thought of anyone else overhearing. And if we switch the analogy, Grumpy is the most adorable of the seven dwarves—except of course for Bashful, and I suspect they are kindred souls, both cut off from conviviality.

There are grumps who are secretly grieving, like the old gentleman in Little Women who had lost his daughter years earlier. When gentle Beth summoned her courage and accepted an invitation to play the lost child’s piano, he melted. Other grumps, though, grieve only the loss of pride. Unwilling to ever be rejected again, they have built a wall of blustery, feigned indifference. Thus they continue to miss what their fellow curmudgeon Samuel Beckett described as “that desert of loneliness and recrimination that men call love.”

The garden-variety grumps are simply dissatisfied. Too much has changed; they cannot find comfort or pleasure; they have lost control. These are not true curmudgeons. They simply need a little spoiling, a little help to adjust.

Real curmudgeons, the finest sort, see the world with clear eyes. Once you read Mencken’s definition of Puritanism as “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy,” it is hard to see it any other way. And I wince with recognition when he calls conscience “the inner voice that warns us somebody may be looking.”

Finally, there is also the nasty, mean sort of grump, but we will not bother with them. Which might be what soured them in the first place: nobody bothering with them….

Medical science offers its own theories about male curmudgeonliness, citing a testosterone decline that can throw emotions off balance and leave men irritable and depressed—then more irritable to mask the shameful depression. Aging also drops dopamine levels, further increasing irritability and moodiness, and it brings aches, pains, and sleep disturbances that can exacerbate. Psychologists toss in their own theory: that when men retire, they lose “professional identity.” In other words, ego gratification. Plus, they have not been socialized to make and keep friends, so they become more isolated.

All valid points, all possible explanations. But why pathologize? Even if an aging body has brought someone to this state of mind, he now has an invaluable new skill set. Paul Fussell—the social historian who diagrammed the extensive class system in the “classless” U.S.—once observed that “anybody who notices unpleasant facts in the have-a-nice-day world we live in is going to be designated a curmudgeon.”

Well, plenty of unpleasant facts need pointing out. And if we want to survive them, says British journalist Aubron Waugh, “all that is left for the civilized man”—or woman—“is to laugh at the absurdity of the human condition.”

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.