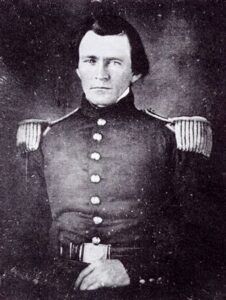

US Grant in 1844, courtesy National Park Service.

When Ulysses S. Grant arrived in St. Louis in September 1843, he was twenty-one years old, weighed 117 pounds, and had a bad cough. Back home in Bethel, Ohio, a barefoot stableman had dressed up like Grant and paraded down the street, apparently drunk, to mock his new second lieutenant’s uniform.

On the plus side, Grant was a graduate of West Point, America’s premiere engineering school in the first half of the nineteenth century, and was being stationed at the largest military post in the country, Jefferson Barracks, which would play an important national role for decades.

Grant excelled at math and riding, “was devoted to novels, but not those of a trashy sort,” and promptly fell in love with his classmate’s sister, who lived five miles west of the Barracks. He and Julia Dent agreed to marry in 1844, but before they could get it done he was deployed to the Louisiana frontier and then to the war in Mexico, and the couple saw each other only once in four years and three months. They finally married in 1848. There were more army separations until 1854, when Grant resigned his commission and returned to St. Louis.

But St. Louis was not always easy for the Grants. He barely held on for four years as a farmer—note the name of his one property, “Hardscrabble,” out where Grant’s Farm is now—and the statue of Grant at Market and Tucker in the city is said to mark a place he used to sell cordwood, which he had felled and split himself, at no great profit. He tried real estate collections and could not make a go; he was passed over for the job of County Engineer. In 1860 he and his family moved to Galena, Illinois, so he could take a job as a clerk in his father’s leather-goods store.

Grant’s prospects did not seem particularly promising, but as he writes in his memoirs, “One of my superstitions had always been when I started to go somewhere, or to do anything, not to turn back, or stop until the thing intended was accomplished.”

Lucky for us. This part of the Midwest produced Grant, Lincoln, John Hay, John Nicolay, and fourteen Union generals, including John Logan, and John Schofield. William T. Sherman lived and worked in St. Louis at times.

The Midwest also provided grain, livestock, dairy, ore, wood, salt, and leather for the Union. Its factories made war materiel, and shipyards in St. Louis and Cairo built Union ironclads. Three-quarters of a million men from the Midwest served—one in eight residents, from a variety of backgrounds.

Mark Twain was a Confederate soldier for two weeks, but his unit of Missouri irregulars disbanded in part because they heard a Union colonel was sweeping through northern Missouri with a regiment to destroy them all. The colonel was US Grant, and of course he and Twain became friends and publishing partners later in life. Huck Finn, published half a year before Grant died in 1885, ties the St. Louis region and the lower River by its action, and lets even a rough child see that slavery is wrong.

Grant’s legacy has been re-evaluated for the better in the last decade, and in the age of neo-Confederatism and Lost Cause devotees, his memoirs still sting:

“For the present, and so long as there are living witnesses of the great war of sections, there will be people who will not be consoled for the loss of a cause which they believed to be holy. As time passes, people, even of the South, will begin to wonder how it was possible that their ancestors ever fought for or justified institutions which acknowledged the right of property in man.”