“Filmmaking is cheating . . .”

—Film Editor and Director Peter Hunt¹

“With Goldfinger, the Bond writers created a new agent, an indestructible man who would survive any situation. It was no longer a question of whether Bond would survive, it merely became a case of which button he would push, or what he would say.”

—Steven Jay Rubin²

Goldfinger, the third in Eon Productions’ James Bond series, was released in the United States on December 22, 1964. In fact, according to Bosley Crowther’s review which appeared in The New York Times on December 22, the film “opened last night” or on December 21, at least in New York. Paul Duncan in his book, The James Bond Archives, states that the film opened in the United States on December 25 (103) and perhaps that might have been an opening date for a broader release, but the film was playing as early as December 21 and in nearly every reference about the film, the U.S. release date is given as the 22nd.

Goldfinger might have had the tagline, “The Biggest Bond of All,” but that was to be used for the next film, Thunderball, which truly was the biggest Bond of all, as it is, adjusted for inflation, the highest-grossing of all Bond films. But Goldfinger had a budget that was bigger than the combined total of its predecessors—Dr. No and From Russia With Love. And it made money faster than its predecessors—both of which were highly successful films—recouping its costs in two weeks after opening in the United States. (And remember Goldfinger was what was then called a “first run” film which means that it played at far fewer theaters than a mass-market film does when it opens in the United States today.)

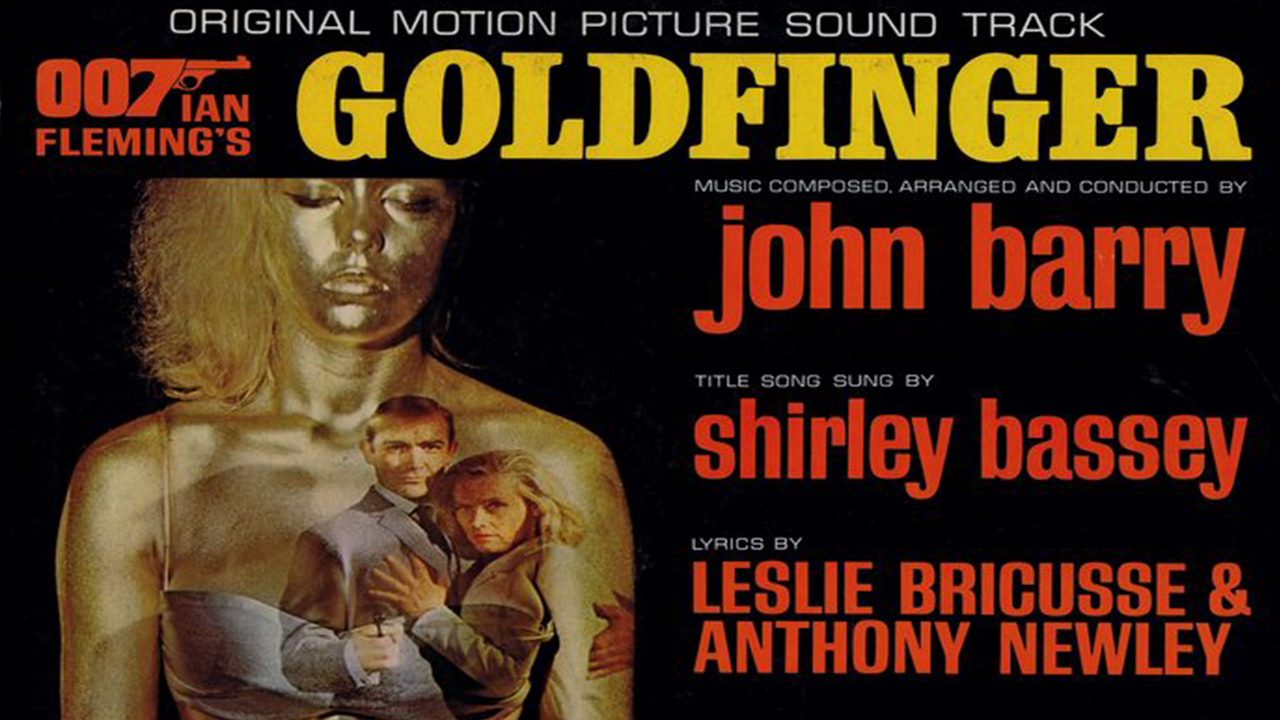

As all the commentators have noted, Goldfinger provided the template for future Bond movies. First, a title song played over the opening credits. There was a title song for From Russia With Love, sung by singer Matt Monro, the British version of Frank Sinatra, but it was played at the end of the film. The Goldfinger theme, sung by bi-racial British chanteuse Shirley Bassey, was a huge pop hit. Every Bond movie since, except On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, has had a theme song, some of which, such as Paul McCartney’s for Live and Let Die and Adele’s for Skyfall, becoming massive commercial successes. (Ironically, in Goldfinger, Bond makes a disparaging comment about the music of the Beatles. The filmmakers, the scriptwriters especially, could hardly be expected to foretell the future!)

Bassey felt she was right for the theme song, “A man should not be singing about James Bond,” (The James Bond Archives, 102) she said. Well, Eon Productions did not take that advice: Welsh pop singer Tom Jones sang the theme for the next film, Thunderball, and he had to hold the final note forever just as Bassey did with the Goldfinger theme. He too, like Bassey, passed out or nearly passed out, as the story goes. Of course, it could be said that Bassey never sang about James Bond; she sang about Goldfinger the character, which, as it happens, turned out to be one of the major problems with the film itself. More on that in a moment.

Second, Goldfinger featured the pre-credits action sequence which has become the sine qua non of the Bond movie. This was the idea of co-producer Harry Saltzman who first used it to great effect in From Russia With Love, when Bond is seemingly murdered by assassin Donald Grant in what turns out to be a practice run of SPECTRE’s plan for the real Bond. But that pre-credits opening is tied to the plot of the movie. Goldfinger introduced the pre-credits opening that has nothing to do with the rest of the film but is meant to be just an adrenalin rush. In Goldfinger, Bond, emerges from the water somewhere in either Mexico or South America, takes off his scuba gear, overcomes a guard, scales a wall, sets timed explosives inside some sort of illegal drug factory, leaves, unzips his wet suit to reveal a dinner jacket, goes to a local tavern where he informs a fellow agent of what he has done. We hear the explosion and Bond is warned to leave as soon as possible. Instead, Bond visits the tavern’s dancer (played by the same actress who was Kerim Bey’s girlfriend in From Russia With Love) in her dressing room where she is setting him up to be murdered but he sees his assassin approaching in the reflection of the girl’s eyes. After a fight ensues between Bond and his would-be assailant, the assailant, falling into a bathtub filled with water, reaches for Bond’s gun, which Bond had hung up in its holster near the tub when he first entered the dancer’s room. Bond, always alert, flings a plugged-in electric fan into the tub, electrocuting his assailant; this also foreshadows the end of the movie when he electrocutes the far more formidable assassin, Oddjob, Goldfinger’s problem eliminator. Bond leaves the room muttering, “Shocking. Positively shocking.” Boom. Opening credits with Bassey singing the Goldfinger theme. Every Bond film after this would use a bigger, more spectacular version of this type of opening, which would usually be unrelated to the movie that followed.

Third, Goldfinger made technological and mechanical gadgets a permanent aspect of the Bond film effect. The Aston Martin DB5 with machine guns, oil slick, smoke screen, hubcap tire slasher, bulletproof windows, ejector seat, and electronic tracking, was almost as much the star of the movie as Sean Connery was. In the first film, Dr. No, Bond was simply given a better gun, his Walther PPK. In From Russia With Love, the gadget as gimmick truly begins with Bond’s attaché case which has a hidden cache of bullets, a sniper’s rifle, a dagger, fifty gold sovereigns tucked away, and a canister of tear gas that explodes in the face of someone who incorrectly opens the case. All of these come into play in the film to save Bond’s life. The car in Goldfinger is a glamorous idea for a weapon but it does not save Bond’s life, in the end. It fails to help him escape the clutches of Goldfinger. It is no wonder that Goldfinger does not think the car is very “practical.”

Goldfinger gives the audience the full Bond treatment: a megalomaniac villain with a ridiculous name (Goldfinger), a heroine with a ridiculous name (Pussy Galore, who, in the Ian Fleming novel is a lesbian that Bond, through coitus, “converts” to heterosexuality which Honor Blackman, the actress who played the character, found hysterically funny, (The James Bond Archives, 91)), and a ridiculous plot (robbing Fort Knox or, more precisely, irradiating the gold there). All of this is tongue-in-cheek, of course.

I saw Goldfinger when I was about 12 or 13 years old, some weeks after its initial opening in the United States. I was a big Bond fan. I loved From Russia With Love. Yet Goldfinger disappointed me and I did not see another Bond in a movie theater until 1971 when Connery returned to play Bond in Diamonds Are Forever (Bassey sang the theme song for this one too). I went only because my mother wanted to see it. What I loved about From Russia With Love were the villains Bond faced—Donald Grant, Rosa Kleb, Kronsteen. They were fascinating to me as a boy and I wanted them actually to have an even bigger role in the movie than they did. I also loved the character of Kerim Bey, Bond’s Turkish ally. At the time, I did not realize that part of my thralldom was because the actors who played these roles were so good: Lotte Lenya, Robert Shaw, Pedro Armendáriz, who was dying from cancer during filming and, like his friend Hemingway, committed suicide days after his part was completed, and Vladek Sheybal. The plot had real suspense because I was not sure that Bond would survive. As I look back, the film would have had even more suspense if the character of the defecting Russian file clerk, Tatiana Romanova, had been more clever and scheming, and made the audience more unsure if she was simply using Bond. It is said that when casting that part the producers were looking for “Greta Garbo with tits.” (The James Bond Archives, 59-60) It is too bad that they could not have gotten Garbo herself, who would have made the character more complex.

But for me Goldfinger was simply outlandish, a dumb spectacle. And once Bond was captured by Goldfinger, the film became a dull captivity narrative. (It was completely implausible to me, even as a boy, that Goldfinger would have kept Bond alive. There was no logic to it. The laser beam Goldfinger threatened Bond with should have finished its job and cut Bond in half. There is no way Bond could talk his way out of it.) Bond seemed terrible at his job, adolescent. I was thinking as I watched the film that Dr. No was right: Bond was nothing more than a stupid policeman. Connery was right in his misgivings about the film: that Bond was nothing more than a kind of supporting player in the film. Goldfinger’s part was better. Connery was also mystified that the film was such a monster hit.

But for me Goldfinger was simply outlandish, a dumb spectacle. And once Bond was captured by Goldfinger, the film became a dull captivity narrative. (It was completely implausible to me, even as a boy, that Goldfinger would have kept Bond alive. There was no logic to it. The laser beam Goldfinger threatened Bond with should have finished its job and cut Bond in half. There is no way Bond could talk his way out of it.) Bond seemed terrible at his job, adolescent. I was thinking as I watched the film that Dr. No was right: Bond was nothing more than a stupid policeman. Connery was right in his misgivings about the film: that Bond was nothing more than a kind of supporting player in the film. Goldfinger’s part was better. Connery was also mystified that the film was such a monster hit.

What disappointed me most was that the filmmakers took all the aspects of Bond that I found as a boy the least compelling—the gadgets, the bad jokes, the smutty sexuality, the implausibility—and blew them up and made them the Bond experience. I felt cheated. The filmmakers missed the whole point of Bond. I could not watch a Bond film again for years with any sense of enjoyment until I discovered a different prism through which to understand them. The first thing I learned as an adult was that movies are supposed to be a cheat.

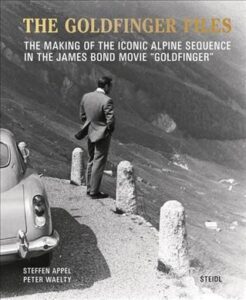

I recently read The Goldfinger Files: The Masking of the Iconic Alpine Sequence in the James Bond Movie “Goldfinger” by Steffen Appel and Peter Walty, a coffee table book with plenty of wonderful candid pictures of the actors, the production team, and the locations in Switzerland where part of Goldfinger was shot. The team found it hard to get a hotel because no one especially wanted to accommodate a film crew. Connery apparently diddled a hotel worker and two men on the crew who were lovers had such noisy sex (the walls were thin) that their secret was hardly a secret. The Alpine sequence, with Bond and the character Tilly Masterson, played by Tania Mallet, following Goldfinger in a leisurely sort of cross country chase, as Goldfinger drives to his gold smuggling plant, is among the most scenic in a Bond movie. The photo of Connery as Bond leaning against the Aston Martin on a Swiss road is rightly famous. I have never seen Connery as Bond look better. I very much enjoyed the book and highly recommend it to anyone interested in how filmmakers go about their business. I learned from this that I would much rather read about how Goldfinger was made than watch it.

• • •

¹Paul Duncan (ed), The James Bond Archives, (Cologne: Taschen, 2015), 76.

²Mark A. Altman and Edward Gross (eds.), Nobody Does It Better: The Complete Uncensored, Unauthorized Oral History of James Bond, (New York: Forge Books, 2020), 143.