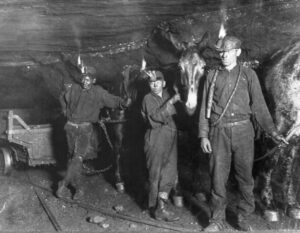

Lewis Hine, child coal miners, West Virginia, 1908. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, Records of the National Child Labor Committee

One of my grandfather’s first jobs was child coal miner, family lore says. My other grandfather, also born in the 1880s, would have labored on the family farm or, more likely, on land they worked as sharecroppers. My grandmothers as children and teens would have worked the crops and labored in the home, helped raise siblings, made meals, and worked the sad iron.

My father, who was born in 1918, had a nearly identical early life. He worked the sharecropper plot, including through the Depression and its droughts, went into the CCC as a teen, then joined the wartime army. (My mother’s family was well-to-do for their region, and I do not remember her mentioning having a job until after she graduated college; obviously class, race, and location matter in the topic of first jobs.)

I grew up in a little subdivision house in a former coal town. Some things were still recognizable from earlier generations: We did not have a TV or air conditioning (or sometimes heat, full plumbing, or appliances), and my childhood usually moved at the pace of walking or the bicycle. My sister, ten years older than me, volunteered as a Candy Striper then put the curl on cones at the Dairy Queen.

My first paid job, at eight or nine, was mowing lawns, usually for friends of my mother. Some of those yards were big enough that any sane person today would use a riding mower to cut them. The ladies seemed to cultivate thistle, wild blackberry brambles, sinkholes, vicious weeds, and hidden rocks big enough to break the shear pin on the mower.

Because my mother was on her own, she took pity on the ladies, who were also older and alone, and gave them a deal on my labor. I seem to remember $2, $5, and $7 paydays for double-lot work. Even at the time it seemed stingy, since I had to buy gas and oil, shear pins, and blade-sharpening. But then if I had decided to run away from home for being treated so miserably, $5 would have put 12 gallons of gas in the car, with change left over for a pack of Pall Malls.

As a teen I worked at a state park, feeding the cottonmouths, copperheads, Mississauga rattlers, pythons and boas in the interpretive center. I picked some fruit and sold it to the supermarket and a restaurant. I washed dishes and bussed tables at the same restaurant, played sax for pay at weddings and fashion shows, moved up to fast food—the majors for teens in our town—and was bailed out by that great federal socialist program The US Army.

Interestingly, a graph at the US Bureau of Labor Statistics site shows the approximate year of my entry into the lawn business (1971) as the start of a slow and then precipitous decline in “teen labor force participation,” expected to continue to 2024. (Federal data notoriously lags; the BLS study is five- to seven-years old.)

“A number of factors are contributing to this trend: an increased emphasis toward school and attending college among teens, reflected in higher enrollment; more summer school attendance; and more strenuous coursework. […] Teen earnings are low and pay little toward the costs of college. […] Teens who do in fact want jobs face competition from older workers, young college graduates, and foreign-born workers.”

The US was also moving away from industry and small-scale agriculture in the last half century and toward the service industry and (eventually) the wired economy.

Despite some anxiety that there were no jobs for teens in the two towns we have lived in, my sons got first jobs relatively easily and, even better, had some choice in what kind of work it would be. My elder was a lifeguard at a country club and taught swim lessons as his first job; my younger did color corrections on picture files for an online art business during the COVID lockdown.

My elder son hustled and has paid for many of his university expenses so far by working as a resident advisor in the dorms. My younger son was hired recently by a large restaurant chain but heard by Yelp and word of mouth their management was poor. As he waited to be told to report, he hustled and found a job bussing at an upscale restaurant instead. The chain, one of those you hear saying they cannot find people to work, never did call to ask him to start.

He came home his first week flush with shared tips and an appreciation for his coworkers, who he said were like friendly older brothers and sisters. (Due to the pandemic and a broken leg before that, he has been trapped at home a lot in recent years.) He stood in the living room in his sharp work outfit, the man in black, and spread a short stack of twenties up his forearm before he tucked into the dinner I had kept warm for him and went to his room to play video games with his best friend, who lives in Guam. I would say he could make it a lot farther if he decided to run away from home, but there is no reason to want to.