My brain fuzzed into a golden haze by some seriously good wine, I lean against my husband and squint at the tiny print of the Riverside Shakespeare in his lap. We lug this heavy tome to our monthly Shakespeare dinner, reluctant to trade it, as our friends have, for a sleek Kindle. This month, we are on Act II of Much Ado About Nothing, and because I prefer the tragedies, my thoughts have already turned to the dinner that will follow.

My brain fuzzed into a golden haze by some seriously good wine, I lean against my husband and squint at the tiny print of the Riverside Shakespeare in his lap. We lug this heavy tome to our monthly Shakespeare dinner, reluctant to trade it, as our friends have, for a sleek Kindle. This month, we are on Act II of Much Ado About Nothing, and because I prefer the tragedies, my thoughts have already turned to the dinner that will follow.

I brighten awake when our resident theater critic, Gerry Kowarsky, assigns me the role of Margaret, a lower-born but fashion-conscious young woman with a wit as bawdy as the bard’s. I speak her lines with relish.

A long silence follows.

We look around the circle, grinning like schoolkids when somebody has dozed off. “Mark?”

“Not my turn,” he says. “It’s Balthasar.”

“Nope, Borachio.”

“My text says Balthasar.”

“Mine, too.”

“Not mine. Borachio.”

Our various devices, paperbacks, and clunking hardbound editions are split fifty-fifty on who should utter the next line: Balthasar, a flirty musician, or Borachio, already Margaret’s lover, whose name means “drunkard” in Italian.

We flounder a while longer, then take matters into our own hands. Mark reads the line. All ends well. But on the drive home, I remember that moment of confusion. Who spoke the line was utterly irrelevant to the action of the play, but it was a tiny, niggling inconsistency that felt like a clue to…something.

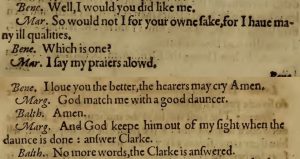

Kowarsky is still thinking about it, too. The next morning, he emails us all an image of the passage in question, taken from the first quarto edition. Margaret is talking with Benedick, then switches to…wait for it…Balthasar. The Folger Library edition even adds a stage direction—“They separate; Benedick moves aside; Balthasar moves forward,” a sort of minuet to clarify the change. Later editions prefer Borachio, with Balthasar playing the background music.

I email back, curious which speaker Kowarsky prefers.

“In production, I like the idea of introducing a relationship between Margaret and Borachio before Borachio mentions it in the next scene,” he replies. “In a staging I saw a number of years ago, the two were communicating silently in the opening scene. The fact that I still remember that detail tells you how much it impressed me. That doesn’t mean, however, that I think a printed text should alter the speech prefixes to Borachio. Editorial decisions should not be made in isolation.” He adds a long caveat about the need to study textual and dramatic context—entire careers are devoted to these pesky textual questions. “Read the Text essay in the Arden edition,” he urges.

And so I do.

There is only one authoritative early text of Much Ado, I learn: the Quarto of 1600. It was registered, and a fee paid, as “a booke The com[m]edie of muche A doo about nothinge/a booke to be staied.”

No one is sure what “to be staied” even meant. Probably an effort at some sort of copyright. The quarto was then printed, titling itself “Much adoe about Nothing./ As it hath been sundrie times publikely/ acted by the right honourable, the Lord/ Chamberlaine his seruants.”

Except it had not been “sundrie times publikely acted,” the Arden edition notes. It could have been staged a few times, but the quarto was “printed from Shakespeare’s ‘foul papers’”—early rough manuscripts which had not as yet “undergone such polishing as might have been necessary before it could be held to represent a satisfactory performance.”

And we know that how? From the light punctuation, sketchy stage directions, and inconsistencies of dialogue and speech prefixes in the quarto. (A speech prefix is the way the character is identified, either by name or by function, as we might choose between “Jeeves” and “the butler.”) Foul papers tend to abbreviate, so the name could have been Bal. or Bor, easy to misread. Characters enter scenes but never speak once, or play any discernible role; some may be artifacts of a plan gone awry. Foul papers are unpolished, merely a snapshot of Shakespeare’s mind at a given point.

However rough its source, the quarto was printed. It had been typeset (by hand of course) by a single guy, later dubbed Compositor A. We think this because Compositor A had a stubborn habit of refusing to punctuate unabbreviated speech prefixes. Also, Much Ado uses a ton of capital B’s (Beatrice, Benedick, Borachio, Balthasar), and the pattern of roman and italic convinced the scholar John Hazel Smith that the typesetter plucked the italic Bs from the form the instant a sheet was printed and dropped them into the composition of the next page.

I read on, skimming for the Borachio/Balthasar dilemma. The quarto has Margaret sparring with Benedick, then switching to flirt with Balthasar. A later edition gives her a stage direction: “turning off in Quest of another] to clinch the switch. But still later editions keep Margaret with Balthasar for the entire exchange, reluctant to have Benedick divide his attentions between Beatrice and another woman. The exception is J. Dover Wilson’s Cambridge edition, which argues that the quarto’s stage direction was a misreading and B should be Borachio.

I sigh. Much ado about everything. Foul papers were supposed to be followed by fair copies, smoothing these details. With a diffident explanation about our little monthly group of amateur Shakespeare lovers, I beg Joe Loewenstein, professor of English at Washington University and a specialist in Renaissance literature and the history of printing, for his take.

“There are layers of answers to a question like this,” he replies. “Not only were there many different kinds of manuscripts and variations of spelling, but different attitudes toward Shakespeare at different times also affected the ways in which he was edited. Namings were often inconsistent, and sometimes that was caught when the manuscript was copied or printed, and sometimes it was not. “Minor characters’ names often seem to get changed on the fly. If Shakespeare hasn’t used their names in verse lines, he’s often apt to shift names when the names are simply placeholders in his mind.” A character might be only “Gentleman 1,” or, if Shakespeare already has an actor in mind, he might use the name of the actor in the script instead of the name of the character. (He did this in Much Ado, substituting Iacke Wilson, a singer of the day, for Balthasar.) “But if Gent 1 comes into focus for him as a person, he may start using a name.”

I imagine Shakespeare rolling his eyes at this entire debate, eager to see his work performed and not quibbled over. “We have very few of his plays that seem to carry evidence of having been prepared for print publication,” Loewenstein says. “His contemporary, Ben Jonson, seems often to have fussed over preparing his plays for publication, providing stage directions and, in some cases, marginal notes. But by and large, Shakespeare is writing for performance.” The play’s the thing, in other words, and you can be sure that directors and actors will be forever toying with it.

Balthasar and Borachio are hardly the only confusion in Shakespeare—though they are a fun example, inserted in a play that is all about confused identities. “A quarto might use one name for a character, and the folio may use a different name,” Loewenstein says. “Shakespeare sometimes lost track of things, sometimes sharpened his attention, and sometimes carefully revised. Sometimes he cut hastily. Sometimes other people messed with his plays.”

I am beginning to think it a miracle that so much exquisite language survived the game. The Arden edition admits that “what is presented here is not the text of the original performance. It is not the text of any performance, and indeed it is intended to be open-ended rather than restrictive (not to be confused with indecisive) in suggesting possibilities for stage action.”

So it really is up to us? “Within limits,” Loewenstein says firmly, “controlled by what we know about habits of writing, habits of copying, performing, and printing that make some things probable and others not.”

Dizzied by four centuries of detective work, I am sure of only one thing: I will never read Shakespeare’s lines with the same flat certainty again. So much of what we think we know in life turns out to be a foul draft, not yet settled into timelessness.