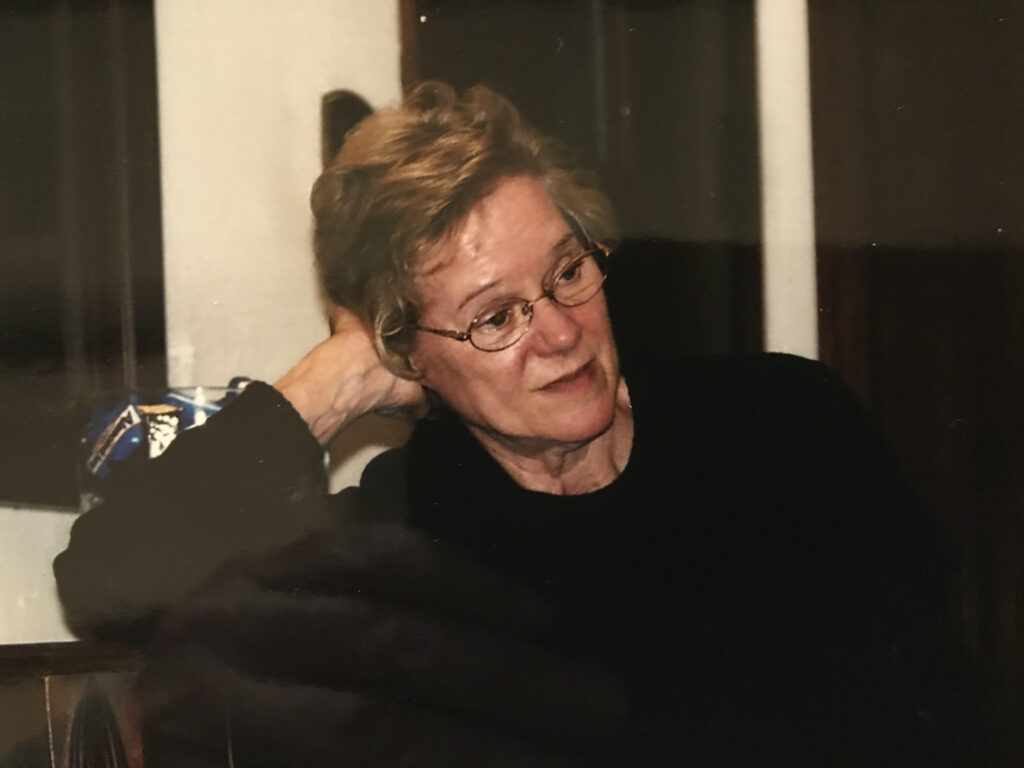

JoAnn Cooperman

The body changes over time, grows creakier, squeakier, crinklier, wheezier. Once those you love hit a certain age, the changes are seldom hopeful. And if you try to get a prognosis from a medical professional, you get as many answers as a Catholic who goes priest shopping.

The problem is the same in both situations: No one really knows. The obliging sort will tilt their guess in the direction they know you prefer. Others tilt in the direction they prefer—or they weight the prognosis with what they would find unbearable. When a nurse saw how a stroke had weakened my mother-in-law, he shuddered and warned us that she was not likely to make it through rehab. In whispers, he urged hospice; her neurologist, a more cheerful chap, urged lots of therapy. Jo’s blood thinner could not have been expected to prevent all strokes, he added, “because with our medications, we are only playing with God,” asking for reprieves and extensions to what is already reality.

I liked his honesty. Drugs and machines and experts spin a sense of certainty, a collaborative fantasy we all prefer. Yet a 2000 study in the British Medical Journal found doctors’ predictions accurate only twenty percent of the time—and that was for patients already diagnosed with terminal cancer. Denied that “crystal ball” they keep reminding us they do not possess, all we can do is take life as it is presented to us.

While spiritual, the strategy does not lend itself to decision-making. Do we disassemble Jo’s current home? When do you try to freeze somebody’s life, put everything in storage as an act of hope? The doctors are not betting on the odds that Jo will be able to return to her pretty assisted-living suite with the garden terrace, but she is. As I spoon pudding into her mouth, she writes that she wants to go home. I ask this gloriously stubborn woman if she feels ready (given that this is the first day in ten that she has even been able to move of her own volition), and she writes, “Yes.”

We do not age with uniformity. Asked to put socks on, Jo raises one slender leg high in the air and effortlessly slides on the sock, graceful as a ballet dancer. The doctors say she has congestive heart failure. They also say her heart is doing great at the moment. Both are true, because not only do various parts of our body age differently, but we also slip in and out of time, one minute succumbing to life’s wear and tear, the next minute vigorous again.

Tired out by pudding, she lies on her side for a nap, her back a seashell’s curve, her expression distant, as though life is only washing over her. Her sleep feels more like a withdrawal than a rest. Is she dying? We cannot tell. Her “vitals” are strong but untested, supported by oxygen, slid along on soft surfaces. There is no way to know what to think or feel or expect. This is true in the rest of life, too, but we are better able to fake certainty.

• • •

Several more days of sleep, and Jo is definitely better. Also furious at her captivity. They move her to rehab, and on video chat, I ask if she likes the nurses, thinking she is alone in the room, and she pushes the air away in disgust. Then a fresh-faced young nurse in candy-stripe antlers sticks her head in front of the screen and promises, “She likes me!”

Grinning, I say goodbye and return to our dining room, now crammed floor to ceiling with all of Jo’s possessions. She likes to wear tops and long-sleeved blouses over them, so I dig through hundreds of thrift-shop finds and pair sets of tops on single hangers. This gives my matchy-matchy soul deep satisfaction. She will look so pretty, I think, pleased with myself. But what right have I to pair up her stuff? Knowing Jo, she will unhook the hangers and make her own choices anyway, as well she should. I am just imposing a little temporary order, because stuff becomes chaos the minute its owner is gone.

Jo graduates from rehab and moves to a nursing home. It will be months, we explain, before they know if this is permanent or not. The place is clean and friendly and warmhearted, and every morning she hugs the sweet kid who comes to help her bathe. We buy her a new recliner, bring books and a few more matchy sets of clothing every week. She is herself again, and the nurses laugh in fond exasperation every time they bump into that strong will. “I hate purée,” she writes in note after note. When Andrew takes her to the dentist, she scrawls, “I want to stop at McDonalds for a Big Mac.”

“Mom, they’d have to puree it anyway,” he says, helpless, and she glares at him.

One night she sees her roommate eating fresh pineapple and somehow gets into the kitchen and nabs a cup. She sneaks back to her room and holds up the cup like a trophy. Her roommate gasps: “JoAnn! You’re not supposed to have that!” Jo grins, tilts back the cup, and drinks some of the juice. A few bits of pineapple come with it, and then she is choking, gasping, and her roommate presses the button, and they do the Heimlich right away, and pineapple comes flying, and the paramedics rush in and try everything they can, and yet she is already gone. That fast.

Andrew does not know whether to laugh or cry. She choked to death on stolen pineapple? It is so Jo.

We say goodbye and go home, numb. A few weeks later, the coroner calls to tell us that Jo’s airway was unobstructed by the time she died; the actual cause of death was a heart attack. Her heart was indeed worn out—yet still capable of one last grab at pleasure, mischief, being.

That much, we could have predicted.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.