I spend Sunday morning reading about extremists and QAnon and toxic masculinity and people who still refuse to wear a mask, and just as I am about to give up on the human race, I open this message from Susan Kerth:

I spend Sunday morning reading about extremists and QAnon and toxic masculinity and people who still refuse to wear a mask, and just as I am about to give up on the human race, I open this message from Susan Kerth:

I texted a good friend here at my condo building that I had the ingredients for one of my favorite dishes that they serve at Katie’s Pizza: honeydew melon wrapped in prosciutto, topped with chopped basil and pistachios, and stracciatella cheese smeared on the plate, and drizzled all over with balsamic glaze. It’s so good! Anyway, I asked her if she and her husband would like some if I made it wearing gloves and a mask. She said her husband said, ‘Hell, yes!’ And that he is planning which wine to drink with this treat and pulling out the good china. Isn’t it funny/sad that in these weird times, even the smallest gestures can make us so happy?

Funny/sad? I know exactly what she minds, but I find it hopeful. And a sweet relief. Pre-pandemic, I was convinced that we were losing our ability to interact in any way warmer than a thumbs-up emoji. When even good friends kept their phone on the restaurant table, glancing down from time to time during our deep and heartfelt conversation, I decided we were done for as a people.

I tried hard to remember the insistence of my favorite Jesuit, Fr. Walter Ong: “Technology is morally neutral”—and you do not blame the medium for the way people use it. When critics shrilled that television was hurting young minds, Father Ong had smiled and pointed out that Plato issued the same warnings about the written word, predicting it would destroy our memories and its ambiguity would twist our relationships. Thamos, King of Egypt, added that writing would make people lazy—which the Cassandras shouted all over again when TV turned us into couch potatoes.

We survived writing, and we survived television, but surely the internet was exponentially different? I felt sure that if Father Ong were still alive, he would give that small, amused smile and concede that this new screen addiction was indeed endangering our humanity. Everyone around me seemed hyperstimulated and easily distracted, their nerves jangly, their flesh-and-blood relationships neglected. Screens were stealing our souls.

I was so wrong.

The screens were not the problem. Our mental state was the problem. Nearly all of us were overworked, overcommitted, and overwhelmed, and the technology was merely an enabler; take it away, and we might have shuffled notepaper with the same frantic energy.

I am in front of one screen or another much of every day now, but it no longer feels dehumanizing or disconnected. It feels life-affirming, a safe chance to converse, learn, laugh, and work without risking contagion. And the screen time is balanced by a ton of time outside, walking or gardening or playing with the dog. Before, walking felt like an obligatory exercise, gardening was often neglected, and I never felt like I had time to play. Subtract a long commute and a slew of urgent errands and meetings that it turns out were not urgent or even necessary, and there is time. I no longer feel harried. I am not pushing my computer to do five things at once because it can. Friendship no longer feels like an interruption; it feels vital.

Cynics will explain the recent exchange of kindness in Darwinian fashion, as either an attempt to keep the species alive or a “reciprocal altruism” that does a kindness hoping to count on one in return. But in my experience, whenever people are forced to deal with something that dwarfs their trivial problems and lets all the tiny busyness drop away, they often react with kindness. I have seen this happen in hospital waiting rooms, in natural disasters, after car crashes ….

And now.

Another friend, after reading my worries about the champagne industry, bought me a bottle, saying I had seemed a little glum lately and maybe this would cheer me up. How funny/sad/hopeful, to think a simple gift could alter a mood brought low by large-scale crisis and pain—but it did.

Earlier, I had dropped off some mask elastic, having finally found some that was thin enough not to hurt, for this friend’s sister, and she had sent back a gorgeous multicolored mask for me. People have been sharing homemade sanitizer and disinfecting spray and garden produce; one woman drove round to friends’ porches and dropped off books during lockdown; there are new social rituals with their neighbors, “apps and wine in the cul de sac at 6.” Retired teachers are volunteering to help parents homeschool. The list goes on.

In short, we are still human. More human than ever, now that we have daily reminders of our mortality. All the deaths, nervousness, worries about the future, and carefulness have created an unexpected combination: a constant sense of doom and a gentler, quieter, lower-key life. We laugh more, because it relieves the tension. We stay in touch better, because it matters.

I write this and my finger taps the backspace key, wanting to erase it. The words sound unbearably sappy, uttered in a time and place where people cannot agree on the most fundamental precepts, facts, or necessary actions. Have I just whipped up a rosy dream-world in which to shelter?

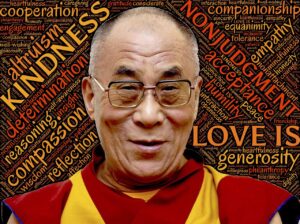

“Negative things are sometimes helpful,” the Dalai Lama told a BBC interviewer, explaining that at times like this, people react in one of two ways. “One way: frustration, anger.” This crisis has sharpened tempers, made people squirrelly, fed conspiracy thinking, heightened anxiety, and depression. But the other way? “You develop a sense of concern, a more compassionate feeling.”

Extremists get the mic. But for the vast middle, those of us deemed naïve by the extremists because we are just trying to figure things out a day at a time, stay safe, and look out for others as best we can, it is these small acts of kindness that keep us going. And they have increased.

There is time. We are not so preoccupied with our private agendas. And our hearts are broken open.