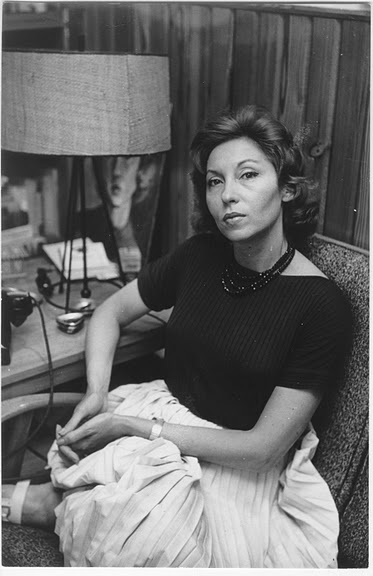

Clarice Lispector (Photo by Paulo Gurgel Valente)

I am trying to understand Clarice Lispector, which is a doomed project, as I am not sure she even understood herself. She could be as coldly lucid as T.S. Eliot, as moody and self-indulgent as Anaïs Nin with PMS. Born in 1920 to a Jewish family that fled Ukraine two years later, she made Brazil her home country—yet kept an accent. Brazilians embraced her as their finest modern author, yet many said her work did not feel Brazilian. Her writing process was intuitive, soaked in emotion, and “entirely unconscious”; you would never guess she had studied law. She presented herself as wild, passionate, shy, and reclusive; a commonplace loving mother and an artist set apart; hungry for God and utterly irreverent.

But then, it is almost impossible for a writer to be honest.

I read Lispector’s admissions of insecurity, indecisiveness, and angst, and I wonder if she is exaggerating, dramatizing her flaws for effect. And then I read her tender words about love and wonder if she has ever felt it. Often I find myself put off, even slightly angry with her, and then she startles me with a line of utter luminosity, clarifying some subtlety that I have sensed but found too ephemeral to articulate. Could I ever write as naturally as she, I wonder, and still go as deep? Ever see the world with as much sensitivity and brave the pain of it? Ever be as bitchy?

Lispector is not especially nice. She knows this. And when she insists again that there is love in her, I am not persuaded. There is need and longing and anger and sensitivity and pain. (Some say writing has to be painful. A man I knew was once rejected by a literary clique clad in black turtlenecks: “You,” they said scathingly, “have probably never even thought about committing suicide.”)

I start with the new collection of her columns, Too Much of Life: The Complete Crônicas, because I am comfortable there. While far more lyrical then any newspaper column you have ever read, they are accessible. Newspapers reached more people than literary fiction, and she clearly enjoyed the casualness and frequency. Her fiction, on the other hand, is startlingly original and mysterious. It has a dreamscape quality; it feels like a locked diary I have ripped open only to find it written in code.

I stop there and sift through a few more novels. When I return to the previous paragraph, I realize I have gotten it wrong. Her fiction is not mysterious or opaque. It is pure emotion, shellacked bright by her intellect, and that is all she intends it to be. She has no need to give us plot.

Instead, like Anaïs Nin, she dramatizes her life for us. These romantics are dangerous, always damaged. I speak their language—just a smattering—and regret it. Because it is a gift to see the world as special, but once you do, it is hard to be content with the world as real.

• • •

Before Clarice was born, her mother was ill, and superstition held that a baby would cure her. “And so I was deliberately engendered: with love and hope,” she writes. “Except that I did not cure my mother.” Is her insecurity a child’s irrational guilt? Is her sense of aloneness a mother hunger? “One of my sons bought a little yellow chick,” she writes elsewhere. “So sad. You can feel in it the lack of a mother.” That lack was in her, too, and it made her a difficult friend, an impossible wife. In one of her novels, An Apprenticeship or the Book of Pleasures, she writes, “‘I love you’ was a splinter you couldn’t remove with tweezers. A splinter buried in the toughest part of the sole of your foot.” A year earlier, she had practiced that image in one of her columns: “I do have love inside me. It’s just that I don’t know how to use love; sometimes it’s more like splinters.” Marriage, to her, was the opposite of splinters (and therefore the opposite of love?). She writes with a sigh about “the cozy nest of resignation.” And here is the biography she gives herself in A Breath of Life: “Quickly, because facts and particulars annoy me. So let’s see: born in Rio de Janeiro, 34 years old, five foot six and of good family though the daughter of poor parents. Married a businessman, etc.” Etc. She had warned her husband from the start that she was not made for marriage. “Inside my body and spirit there vibrated a deeper and more intense life.” Like Nin, she was one of the cursed—brilliant women born ahead of freedom, consumed by romanticism, in need of stability but bored to tears by its mundane predictability. Both women write often about epiphanies shaking up a humdrum life. Yet both are worshipped by husbands too boring to fathom their wives’ boredom, too passive to animate them. Late in life, Lispector tells an interviewer “Too much praise is like too much water for a flower. It rots it.” “It gets frightened?” he asks. “It dies.”

• • •

In his biography of Lispector, Benjamin Moser writes that “she emerged from the world of the Eastern European Jews, a world of holy men and miracles that had already experienced its first intimations of doom. She brought that dying society’s burning religious vocation into a new world, a world in which God was dead.” She goes looking anyway. Not pretending that God is alive, yet searching for God nonetheless. “Let the God come: please,” she writes, describing herself as “an unbeliever who profoundly wants to hand myself over.” She craves a sense of belonging, thinks she must have been born craving it. Yet she refuses to enter any compartments. “One authority will testify that she was right-wing and another will hint that she was a Communist,” Moser notes. “One will insist that she was a pious Catholic, though she was actually a Jew.”

In his biography of Lispector, Benjamin Moser writes that “she emerged from the world of the Eastern European Jews, a world of holy men and miracles that had already experienced its first intimations of doom. She brought that dying society’s burning religious vocation into a new world, a world in which God was dead.” She goes looking anyway. Not pretending that God is alive, yet searching for God nonetheless. “Let the God come: please,” she writes, describing herself as “an unbeliever who profoundly wants to hand myself over.” She craves a sense of belonging, thinks she must have been born craving it. Yet she refuses to enter any compartments. “One authority will testify that she was right-wing and another will hint that she was a Communist,” Moser notes. “One will insist that she was a pious Catholic, though she was actually a Jew.”

Ideology is irrelevant to Lispector; she wants a direct, mystical experience. She wants what she has her main character want in Apprenticeship when she “pretends that she loves and is loved, pretends that she doesn’t need to die of longing, pretends that she’s lying in the transparent palm of the hand of God.”

• • •

“Existing so often gives me palpitations,” Lispector writes. “I am so afraid to be myself. I am so dangerous.” Is she dangerous? Or does she just like thinking of herself that way? “All her life she’d been careful not to be big inside herself so as not to be in pain,” she confides in the voice of a character. In a column, she complains that she is “tired of so many people thinking I’m nice. I like the ones who don’t like me at all, because I feel an affinity with them: I really don’t like myself either.” Life is a struggle for Lispector, and she lets us know that, constantly negotiating with “a world I do not find easy.” “Could it be,” she asks rhetorically, “that the person who sees most, and who is, therefore, stronger, is also the one who feels and suffers most?” I am not sure seeing more does make people stronger, though. Not always. My question is a different one, and will sound mean, but it is something I wonder about. Does intense sensitivity sometimes destroy perspective, leading to anxious self-absorption? She knows she should curb her wild impulses, yet is “afraid, too, of becoming overly grown up.” Anxious about parties—who would say the wrong thing, do the wrong thing, ruin the meal?—she relieved her tension by leaving a few minutes after she arrives. Brilliant in law and philosophy, she reads, for years, only detective fiction. “Living is not an art,” she snaps. “The people who say it is are lying.” But how is she to live, if not as art? She writes of wanting to “give up: lead a humbler life of the mind, except that then I don’t know quite what to give up, I don’t know where to find the task, the sweetness, the thing. I am addicted to living in this state of extreme intensity.” Unable to resign herself to tedium, she devours rebellion “with ravenous pleasure.” And though she sounds like a wayward teen, I love this fierceness in her, because it makes her honest. She is determined to confess in public—not to a priest—“what everyone knows and yet treats as if it were a great secret.”

• • •

“Giving up our animal nature is a sacrifice,” Lispector writes. Animals pad through her writing, and she finds them “very close to God,” living in enviable immediacy, following their instincts with abandon. She pictures “a creature still warm from being born, and yet one that immediately scrambles to its feet, fully alive, and living every minute once and for all, never little by little, never holding back, never wasting away.” In Apprenticeship, a character decides “that animals entered the grace of existing more often than humans. Except they didn’t know, and humans realized it. Humans had obstacles that didn’t get in the way of animals’ lives, like reason, logic, understanding. While animals had the splendor of something that is direct and moves directly.” She admires the way “an animal never substitutes one thing for another, never sublimates as we are forced to do.” Yet in one of her columns, Lispector claims “a certain fear and horror of those living beings that, though not human, share our instincts, although theirs are freer and less biddable.” Is this “fear and horror” an interesting ambivalence or just a literary device? Later she claims that “anyone who recoils at the sight of an animal clearly feels afraid of themselves.” She scorns the sentimentalists: “I don’t humanize animals,” she says. “Instead I animalize myself…. I have to return to wildness every once in a while. I seek out the animal state. And every time I fall into it I am being me.” Not only does she identify with animals, she prefers them to the rest of us. “I woke up in a rage,” she writes. “No, I don’t like the world at all. The majority of people are dead and don’t know it, or else are alive but live like charlatans.” Determined to avoid such sham, she publishes thoughts most of us would stifle. But she is still frustrated—at least says she is—because writing is such a little thing; she would rather have been brave and fought for social justice.

• • •

Clarice Lispector was brave. And the wisdom she left is as alive today as when the ink was wet. In 1967, for example, she wrote, “We have accumulated things and certainties because we have neither the one nor the other. We have failed to experience any previously unrecorded joy. We have built cathedrals, but remained outside, fearing that any cathedrals we ourselves build might turn out to be traps. We have not given ourselves to ourselves because that would be the beginning of a long life possibly devoid of consolations.” Lispector gave herself to herself, and then she poured out most of that self for the rest of us. At the end of The Complete Crônicas, her son Paulo Valente wrote, “Enjoy the columns, I know of nothing quite like them.” In the end, her talent was a mystery—though not the sort she had cultivated on purpose. After traveling to Egypt and seeing the Sphinx, she famously declared, “I did not decipher her. But neither did she decipher me.” She hungered to be enigmatic—but also to be known. She was desperate to escape categories—but also to belong. She managed all of that.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.