It is an era of strange alliances that began for me in the year of the Presidential election, at a protest camp just north of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation, in North Dakota, where an intertribal alliance was trying to stop construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. This was an environmental issue at heart—where DAPL would cross the Missouri River would determine whose water would be polluted if it sprung a leak—but it brought together thousands of disparate people on a snowy pasture in North Dakota.

The camp comprised Native Americans with many views from pacifist to militant, anti-war and pro-thrill veterans, libertarians who pledged allegiance to hating the government, Starbucks liberals, anarchists, crunchy neo-hippies and New Agers, trust-fund kids, alternative-energy proponents, narcs, snitches, agents provocateurs, and those looking for the next new Burning Man. I saw Cornell West, resplendent, and Tavis Smiley, less so. Even the US Army Corps of Engineers, the single organization with the authority to stop DAPL, was split between its operational leadership and political-appointee head.

People saw in Standing Rock’s environmental struggle what they wanted, including the chance to claim Native American sovereignty, to battle racial injustice, or to get their ya-yas playing SEAL Team 6. Participants’ ideologies were often mutually incoherent, but they joined hands from all quadrants of the political compass, willing to put themselves—and perhaps others—in harm’s way for the cause. Many of the thousands came and went without understanding, I suspect, that the cause was a synthesis with complicated histories, which made for odd bedfellows.

• • •

It seems simple. We hurtle through the vacuum of space in a miraculous terrarium that supports life. It is the only one we know of. Caring for its water, soil, air, flora, and fauna seems like a good idea. But priorities get complicated, and you might be surprised at what people think of yours.

Have you been delighted recently by claims that wild animals are “returning” and mountain ranges coming back into view during the pandemic?

Do you think uncontrolled development threatens the natural world? That the doubling of world population within a lifetime strains the ecosystem? That polluting emissions create problems that will disrupt life as we know it?

Even sticking with the made environment, do you pine for a simpler time with “human-scaled, traditional architecture; tree-lined streets; shady country lanes [and] rootedness” instead of congested, ugly cities?

Do we know our ideological neighbors, or where these lines of thought originate and potentially lead?

Or would you prefer back-to-nature homesteading in an almost mythical landscape?

Aspects of all these things have been accused of “ecofascism,” or claimed by actual fascists. Are you—are any of us—innocent of the charge? Do we know our ideological neighbors, or where these lines of thought originate and potentially lead?

• • •

In philosophical terms, not everything said about the relationship of nature and humans is ecofascism.

“Fascism is a handy term to tar people with,” Dr. Michael Zimmerman tells me. “‘Commie’ doesn’t have the same effect these days.”

Dr. Zimmerman was a professor of philosophy, at Tulane and University of Colorado Boulder, for 35 years. He has written extensively on environmental philosophy, integral theory, Heidegger, Nietzsche, and Buddhism. His books include Integral Ecology: Uniting Multiple Perspectives on the Natural World (with Sean Esbjörn Hargens), and the co-edited anthology Environmental Philosophy: From Animal Rights to Radical Ecology.

In his article “The Threat of Ecofascism,” Zimmerman says political opponents sometimes describe environmental activists as “romantic, irrational, nature-worshipping ‘ecofascists,’ who want the government to seize private property in order to protect plants and animals, thereby preventing honest human beings from making a living. Even some environmental philosophers have accused their more radical colleagues of promoting ecofascism, by elevating the needs/interests of the organic ‘whole’ (the ‘land’) above the needs/interests of individual organisms, including animals and humans.”

Michael Moore, whose new environmental documentary, Planet of the Humans, was released on YouTube on April 21, stands accused. Critics say he smears renewable-energy efforts with poor comparisons and outdated data in order to nod at population control. They say this has overtones of eugenics, due to an assumption of high-density populations in the global south.

The idea that (some) humans must be sacrificed for the well-being of the whole does underlie ecofascism. Think of Thanos, the supervillain in the Marvel movies who snaps his fingers in his magic glove and wipes out half of all life in the universe.

(Matthew J. Connelly, Professor of History at Columbia University, and Director of the Hertog Global Strategy Initiative: “When people ask ‘is the world overpopulated,’ I always want to ask them: who did you have in mind? Is there anyone in particular you think maybe shouldn’t have been born? Are there perhaps large groups of people, like millions of people, who you think shouldn’t be here?”)

The idea that (some) humans must be sacrificed for the well-being of the whole does underlie ecofascism. Think of Thanos, the supervillain in the Marvel movies who snaps his fingers in his magic glove and wipes out half of all life in the universe. His intention is good, he insists; by an act of neo-Malthusian charity he will end poverty and misery due to overpopulation. But who wants to be sacrificed for some autocratic, utopian dream?

But Dr. Zimmerman tells me the term ecofascism is not that useful in the United States. It is much more so in Europe, where the ties between white racism and nature-protection are “right up front.” It is so well-known in Germany that there was no Green movement there until the late 1960s, because it was “taboo.” When it did start, Zimmerman says, it had a “significant antimodernist strain, and one of its key leaders had roots in German far-right conservatism.”

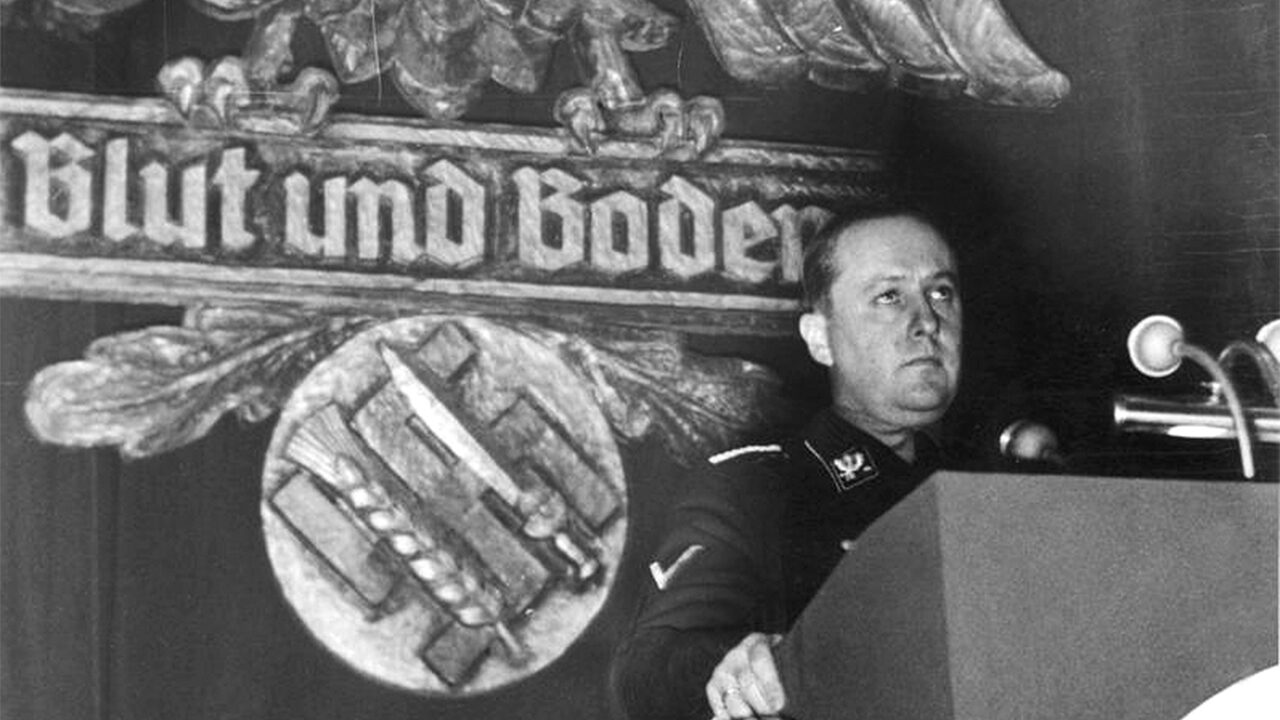

What is remembered, of course, includes the Nazi’s Blut und Boden, or “blood and soil,” the idea of a racially “pure” people in a national homeland with a mythologized past. National Socialists were very interested in wilderness and conservation for this reason, Zimmerman says. They had appropriated the idea of “deep ecology”—”the belief that humans must radically change their relationship to nature from one that values nature solely for its usefulness to human beings to one that recognizes that nature has an inherent value [sometimes with] religious and mystical undertones.” When the Nazis began to arm and industrialize, this was partially abandoned but led to Lebensraum, expanding across borders to seize more “living space” for the chosen.

Dr. Zimmerman tells me the term ecofascism is not that useful in the United States. It is much more so in Europe, where the ties between white racism and nature-protection are “right up front.” It is so well-known in Germany that there was no Green movement there until the late 1960s, because it was “taboo.”

Zimmerman says he thinks Nazis are fascinating to so many people because, unlike communists and capitalists, both modern, Nazis had a reactionary form of modernity. The websites of neo-Nazis blame modern society for everything from low sperm counts to the “decadence” of TV-binging and drinking during the pandemic lockdown. Many long for twee villages from olden days, before things got complicated.

The National Socialists “liked the idea of revolution, just not the ones that led to modern things,” Zimmerman says. “They resurrected [or invented] mythic, racist Aryan beliefs tailored to their situation, and somehow married them to big armies and Messerschmitts. That is ecofascism. What we have is much more complicated,” he says.

“Real fascism requires two things: First, militarism and violence, as you see with Hitler and Mussolini. You have to have thugs, actively repressing. It is only proto-fascistic here.

“The other crucial thing for National Socialism is its anti-Semitic core. The Nazis saw Jews as responsible for both communism—Marx and the Russian Revolution—and capitalism, stock markets. The cosmopolitan and the global were manipulating them, they thought, and they were being torn apart by an international view that made traditional views seem superstitious,” Zimmerman says.

“The horror of impurity and pollution was crucial to the German version of National Socialism. It is this refusal of modernity that marks Nazi ecofascism.”

Zimmerman writes in “Threat,” “In addition to portraying ecological despoliation as a threat to the racial integrity of the people, an ecofascist movement would have to urge that society be reorganized in terms of an authoritarian, collectivist leadership principle based on masculinist-martial values.”

“The horror of impurity and pollution was crucial to the German version of National Socialism. It is this refusal of modernity that marks Nazi ecofascism.”

This is the missing part, so far, in American environmentalism. Zimmerman says American libertarians, for example, are sometimes called fascistic for their dislike of elements of modernity. They do not like FDR or the New Deal state, corporate welfare, income taxes, or international trade. They would of course be at Standing Rock, he says, because they do not like government intervention but believe in property rights, which creates “really strange alliances.”

He gives the personal example of a family friend who owned land near an Exxon facility. The company’s dam failed, and toxic material flowed onto the friend’s private property.

“If they were a typical Republican or Democrat, they would want the company to pay them the price of their property, which was destroyed. The company would have to buy it. But in free-market environmentalism, which is promoted by Libertarians, there is property respect. A libertarian would believe the company was obligated to restore the land, back the way it’s supposed to be. Imagine the difference in cost,” Zimmerman says.

Zimmerman says American libertarians, for example, are sometimes called fascistic for their dislike of elements of modernity. They do not like FDR or the New Deal state, corporate welfare, income taxes, or international trade. They would of course be at Standing Rock, he says, because they do not like government intervention but believe in property rights, which creates “really strange alliances.”

“You could argue that libertarians are modern and could be environmentalists in their way because they respect property rights. Libertarians as fascists is complete bullshit. Collective movements want to sacrifice the individual to the state.”

Still, the American environmental movement must understand its past, Zimmerman says. The US has been far from innocent in its treatment of people in the name of the greater good.

• • •

“In the US, In the Sixties, attacking modernity seemed like a great idea,” Zimmerman tells me. “We didn’t know about the conjoined history of environmentalism and genocide, except for the people who studied it. It was a total disconnect. That’s something we really have to ponder.”

He describes his own “visceral dislike of the industrial,” growing up in northeast Ohio. When bulldozers destroyed forests for development, he knew something had changed forever, including the onset of “environmental amnesia,” “the idea that each generation perceives the environment into which it’s born, no matter how developed, urbanized or polluted, as the norm. And so what each generation comes to think of as ‘nature’ is relative, based on what it’s exposed to.”

“A lot of environmentalism is about how the natural world, as innocent as it is, can be so devastated by modern industry and voracious consumerism,” he says. “I still have feelings like that, but I also recognize human suffering. We can’t be hunter-gatherers anymore. We are way out on the end of a limb.”

The United States was formed in large part by religious and mystical ideas of “special virtues” inherent in white settlers, which came from texts such as the Doctrine of Discovery, and cultural beliefs such as Manifest Destiny. The taking of Native American lands, slavery, and racialized murder came with them, as surely as genocide came from the Others deemed “impure” in the Nazi’s romanticized, reactionary homeland. This white supremacy persisted, even in the desire to care for nature.

“The early conservation movement, the ‘first wave’ of environmentalism, was somewhat elitist,” writes Philip Shabecoff in the New York Times. “Its cadre and adherents tended to be affluent white Protestant males eager to protect wildlife for hunting and fishing and to preserve open space for aesthetics and recreation.”

This refers to men such as John Muir, who had left behind his father’s Calvinism, with its insistence of human domination over the natural world. Muir had ambivalent feelings about Native Americans, who he saw were being pushed off their land (including to make new National Parks), starved, and killed by roving militias. As Muir got to know them, he was better able to articulate his respect, but by that time, as he says in 1901, “As to Indians, most of them are dead or civilized into useless innocence.” Ironically, his eco-centric view intended egalitarianism—to give rights to all living things in nature—but the end result was the creation of a white nationalist homeland.

This was the same era in which Teddy Roosevelt was promoting the ideal of manly toughness, as opposed to being soft or weak. For Roosevelt, wild nature (and war) was the place where both man and country could be forged.

Ironically, his [John Muir’s] eco-centric view intended egalitarianism—to give rights to all living things in nature—but the end result was the creation of a white nationalist homeland.

Gary Gerstle, a professor of American history at the University of Cambridge, uses the usual epithet that Roosevelt was very much “a man of his time,” with “very well-developed and racist views towards both Indians and blacks. He regarded Indians as savages. He respected them because they were ardent warriors. But he expected that they would be eliminated, exterminated from America in contest with the white men who were settling the continent, to the people who he hailed as backwoodsmen. And he required the Indians to be there to be the strenuous opponent through which Americans could prove their valor. But he was very clear that in a modern America that he was building, he expected they would be exterminated either through battle or through simply the inability to adjust to modern life. He would have had no patience with the indigenous and original inhabitants of a sacred American space interfering with his conception of the American sublime.”

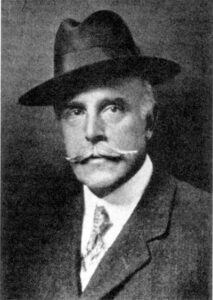

Madison Grant in the early 1920s: friend of President Teddy Roosevelt, author of The Passing of the Great Race, and one of the chief environmentalists of his age. (Image: Wikipedia)

Roosevelt’s friend Madison Grant was one of the chief environmentalists of the age. He is credited with inventing modern wildlife management, saving several species from extinction, and helping create Denali and Glacier National Parks. He also wrote the 1916 “scientific racism” handbook, The Passing of the Great Race, or The Racial Basis of European History, which Roosevelt loved and Adolf Hitler called “my bible.” Grant has been called “the founding father of ecofascism.”

Jeffrey A. Tucker, Editorial Director for the American Institute for Economic Research, writes, “[Madison Grant] was director of the American Eugenics Society and advocated from his post the culling of the unfit from the human population. He mapped a 100-year plan to perfect the human race, killing off group after group until racial purity had been obtained. He favored a state program to ‘get rid of the undesirables’ in jails and hospitals. He warned against ‘misguided sentimentalism’ that would put a break on his murderous plans to wipe out ‘social discards’ and ‘worthless race types.’”

Roosevelt’s friend Madison Grant was one of the chief environmentalists of the age. … He also wrote the 1916 “scientific racism” handbook, The Passing of the Great Race, or The Racial Basis of European History, which Roosevelt loved and Adolf Hitler called “my bible.” Grant has been called “the founding father of ecofascism.”

As Michael Zimmerman says in The Ecological Community, “Concern about racial degeneration was so strong in the United States during the first part of this century that American scientists became the world leaders in eugenics research. Nazi officials relied heavily on that research in devising their own eugenics methods (including euthanasia, sterilization, and murder) designed to ‘purify’ and ‘regenerate’ the German population.”

In addition to studying Manifest Destiny and American eugenics, the Nazis learned much from Jim Crow and American race law, our immigrant quotas and bans, our use of Zyklon-B as a fumigating agent on immigrants, and the mechanics of American gas chambers used to execute criminals.

The taint of savagery working for the glorious whole still underlies the American environmental movement.

Philosopher and ecologist Aldo Leopold famously explained his “land ethic” in A Sand County Almanac (1949), seeming to take pains to evade “blood and soil” ideology:

“The land ethic simply enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land. This sounds simple: do we not already sing our love for and obligation to the land of the free and the home of the brave? … A land ethic of course cannot prevent the alteration, management, and use of…’resources,’ but it does affirm their right to continued existence, and, at least in spots, their continued existence in a natural state. In short, a land ethic changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land community to plain member and citizen of it. It implies respect for his fellow-members, and also respect for the community as such.”

Yet as Michael Zimmerman has written, Leopold’s land ethic was called “misanthropic” by a radical environmental philosopher (he later retracted the charge), and its sentiment was decried by Rush Limbaugh and other demagogues as ecofascist. There were attempts to link the land ethic to the writing of Dr. Walter Schoenichen who, Zimmerman says, “explicitly portrayed his ecosophy as consistent with the…racist ideology of National Socialism.” (Zimmerman adds that Schoenichen made an attempt to leave Nazism out of his philosophy later.)

In the last generation, there was American writer Ed Abbey, whose most famous book is the Walden-like Desert Solitaire. When I read Abbey as a teen, I thought of him as a “liberal,” given his environmental activism and first use of the term “monkey wrench”—“nonviolent disobedience and sabotage carried out by environmental activists against those whom they perceive to be ecological exploiters.” What Abbey actually was, of course, was a city-hating, government-despising, nature-loving libertarian fond of guns, rugged individualism, solitude, chauvinism, and keeping things where they belonged.

In an essay called “Immigration and Liberal Taboos,” written for the New York Times, he says, “Even the terminology is dangerous: the old word wetback is now considered a racist insult by all good liberals; and the perfectly correct terms illegal alien and illegal immigrant can set off charges of xenophobia, elitism, fascism, and the ever-popular genocide against anyone careless enough to use them.”

The taint of savagery working for the glorious whole still underlies the American environmental movement.

He says there are economists “who actually continue to believe that our basic resource is not land, air, water, but human bodies, more and more of them, the more the better in hive upon hive, world without end—ignoring the clear fact that those nations which most avidly practice this belief, such as Haiti, Puerto Rico, Mexico, to name only three, don’t seem to be doing well. They look more like explosive slow-motion disasters, in fact, volcanic anthills, than functioning human societies.”

He lists the societal ills of the US, including “rotting cities and a poisoned environment,” and says, “This being so, it occurs to some of us that perhaps evercontinuing [sic] industrial and population growth is not the true road to human happiness, that simple gross quantitative increase of this kind creates only more pain, dislocation, confusion, and misery. In which case it might be wise for us as American citizens to consider calling a halt to the mass influx of even more millions of hungry, ignorant, unskilled, and culturally-morally-genetically impoverished people. […] Especially when these uninvited millions bring with them an alien mode of life which—let us be honest about this—is not appealing to the majority of Americans.”

• • •

We live in an age of anti-modernity, Michael Zimmerman tells me, in which many are anti-intellectual and anti-science, make appeals to a great homeland, and offer dire warnings “we” are under assault by outside influences—globalism, unfair trade and agreements, the “Chinese virus,” and immigration. They also see enemies within.

“Twenty years ago, far right-wing groups in Germany were already linking their anti-immigrationist platform to the mainstream concern about the environmental impacts of human population growth and population density,” Zimmerman writes. “These days, even mainstream German politicians link immigration to environmental concerns, only now in the context of the renewal of anti-Semitism. Far right-wing groups in the United States have begun to tie public concern about urban sprawl and environmental pollution to immigrants from countries that allegedly fail to respect the natural environment. In the current global situation, environmentalists should continue to promote their agenda, but should also be prepared to dissociate themselves from those who might exploit aspects of it for their own ends.”

He and I discuss how the Norwegian terrorist who killed 69 mentioned Madison Grant in his manifesto. The Christchurch, New Zealand, shooter, who killed 51, called himself an ecofascist and mentioned the Norwegian. The El Paso shooter killed 23, a few months later, and mentioned Christchurch and added his own white-nationalist and “Great Replacement” rants. “If we can get rid of enough people, then our way of life can become more sustainable,” he wrote.

• • •

Michael Zimmerman says Romanticism is easily mixed with racism. “The more you know about it, the better environmentalist you can be.”

He says for a long time the American environmental movements, such as the National Resources Defense Council and Sierra Club, were all middle-class white people. Combine this with how deep ecologists were often not as concerned with inner cities and their people, and something had to change.

“In the last 20 years [those organizations] were forced to reckon with that. Black and brown and poor white people had to be let in. The environmental justice movement held their feet to the fire, and they have come around, to some extent.”

“People didn’t become ‘environmentalists,’ as we know them, until well into modernity, when decreasing numbers of people had to hack out a living by growing things and herding animals in the open.”

He tells me there was a point early on where he realized “the Sierra Club has power interests, and they are not right all the time, and the same goes for all those who have an environmental agenda. All groups play power games in DC. Exxon has an interest in what they do, and we rely on their oil. We are all dependent on modernity. No one is innocent; all are involved in it. It was a real awakening, this point of view.”

Zimmerman tells me, “There’s a reason that humans fear comets. If people had known that ‘nature’ caused all those awful plagues over the centuries, that would have been another reason to fear nature. In fact, one reason for the rise of modernity (via industry and science) was that it promised to improve the human estate, which until then had largely been subject to chance, including droughts, floods, blizzards, heatwaves, locusts, rabid wolves, diseases, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tornadoes, hurricanes, etc. People didn’t become ‘environmentalists,’ as we know them, until well into modernity, when decreasing numbers of people had to hack out a living by growing things and herding animals in the open.”

• • •

Alliances get confusing. Even white nationalists understand that. Counter-Currents Publishing, which considers itself the academic heart of white nationalism (“We live in a Dark Age, in which decadence reigns and all natural and healthy values are inverted”), ran a piece in their online magazine that said:

“[W]hat I have called Ur-Ecofascism is so vaguely defined that its principles can actually be held by individuals of vastly different political orientations: reactionary traditionalists like Thomas Malthus; turn-of-the-century Progressives like Madison Grant and Theodore Roosevelt; National Socialists like Savitri Devi and Heidegger; latter-day authoritarians like Pentti Linkola; conservatives like Garrett Hardin; anarcho-tribalists like the early Earth First! crew; and leftist vegan anarchists like the Animal Liberation Front saboteurs. [But] ‘ecofascism’ has such a pejorative ring that its use outside of hostile polemic is unadvisable.”

The publication itself seems to have no such qualms.

• • •

With a plague of environmental origin upon the land, I think of members of the Patriot movement, long-gun people, anti-vaxxers, COVID-deniers, what is left of the original Tea Party, and those who want Baskin Robbins real bad, seen stalking the halls of government together. It is a strange alliance, but they are almost exclusively white. Victims of the disease are disproportionately black and brown.

I think of Mike, who lives an hour south of Moscow. He was very kind to my friend and me, and we bonded over world literature. As he drove us around town, he pointed to people on the street and said they were Central Asians who had swarmed in after the collapse of the Soviet Union and still did not speak Russian, had different ways, and depleted local resources. He angrily pointed at EU bonding warehouses built on what had been beautiful fields of grain. He spoke of retaking Novorossiya—Ukraine. When he learned we lived in Virginia and Louisiana, he repeatedly called us, and himself, “Confederates,” and made the point several times that Poroshenko was like General Sherman: “Understand?” Outside town on a lovely country lane he pointed to mechanical harvesters destroying a forest of Russian birches, because foreign boring beetles had snuck in and ruined everything.

I think of a matriarch at Standing Rock, who believes the white world order is disintegrating, and only the indigenous know the way forward, due to their relationship with nature. She and her peers had been in conflict with the radical young men in their communities, who wanted violence in the #NoDAPL fight. Tribe members appreciated that President Obama visited their reservation in 2014, and that he directed his Corps of Engineers to pull the DAPL permit in 2016, before blood could be spilled. Yet they bristled on social media when he said, in his national commencement address last week, “What we’re fighting against is these long-term trends in which being selfish, being tribal [my emphasis], being divided, and seeing others as an enemy—that has become a stronger impulse in American life.”

With a plague of environmental origin upon the land, I think of members of the Patriot movement, long-gun people, anti-vaxxers, COVID-deniers, what is left of the original Tea Party, and those who want Baskin Robbins real bad, seen stalking the halls of government together.

I also think of their disbelief, both angry and amused, that white dudes came out for Stand with Standing Rock and immediately began hammering-together permanent, wood-frame buildings, in a protest camp of tipis and yurts, and trying to co-opt organization of the movement to protect the water. One matriarch spoke then of the “settler mind” of those coming to the camp—those who, as if it was “in their DNA,” began building houses and “scrapping for space.”

I think of my white veteran friend who said we had all gone there “without understanding the actual dynamic at the camp or the purpose of everything to do with the camp or the way in which the protest is performed—but yeah, that was my engagement with my own colonial impulse, my own genocidal fucking thing that I guess is buried in us all.”