“In the summer of 1968, I mastered my craft.”

—Bob Gibson, Stranger to the Game: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson[i]

Why pitching is such a great athletic feat

There are two entities that are awarded victory when a professional baseball game is won: the winning team and a particular pitcher on the winning team. How the team is credited with a win is simple enough: it must score more runs than the other team either during what is recognized as the regulation time for a game (nine innings normally; five innings for a game stopped by inclement weather) or during extra innings if the game is tied after nine innings.

For a pitcher to get a win is a bit more complicated:

- The starting pitcher can get credit for a victory if he pitches at least the first five innings and, if he is taken out at any time after the fifth inning, his team is ahead and does not ever relinquish the lead.

- If the starting pitcher is unable to go five innings due to injury or ineffectiveness but leaves the game with a lead that is never relinquished, then either the relief pitcher that pitches the longest or is judged by the official scorers of the game to be the most effective will get credit for the victory.

- If the lead changes during a game, the pitcher who is pitching in the inning that the winning team goes ahead and keeps the lead, whether it is the starting pitcher or a relief pitcher, is credited with the win. It does not matter if the relief pitcher pitched to only one batter; if he is officially the winning team’s pitcher when that team takes the lead, he is credited with the win. He is what is called the “pitcher of record.”

Relief pitchers earn their keep by doing other things than getting credit for victories, and so are not very concerned about won/lost records as long as they pitch well and their team wins. Starting pitchers, on the other hand, are measured mostly by the number of games they win. And how they win them. “These days,” Gibson writes in Pitch by Pitch, reveling in his old school prejudices, “sabermetricians tell us that wins are a poor way to judge a starting pitcher. To me, they were everything.” Starting pitchers are the same today as they were in Gibson’s time: they measure their success on the field and the money they can command in their contracts by their wins. Winning is the still the measure by which all things are made intelligible in sports. Why teams get victories is obvious: that is the point of the game. Why pitchers get wins is because they are central, crucial to the team’s success. A team’s fate is in the hands of its pitchers, whom one pitching coach described as “the fulcrum” of all the action on the field, not the trigger but the gun itself.

Relief pitchers earn their keep by doing other things than getting credit for victories, and so are not very concerned about won/lost records as long as they pitch well and their team wins. Starting pitchers, on the other hand, are measured mostly by the number of games they win. And how they win them.

Why Bob Gibson was great

“I was proud of my slider. . . . With the slider, in fact, I had become the mentor.”

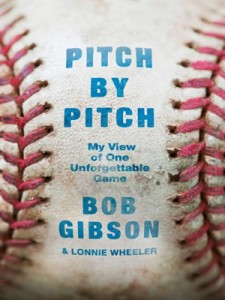

—Bob Gibson, Pitch by Pitch: My View of One Unforgettable Game, (emphasis Gibson)[ii]

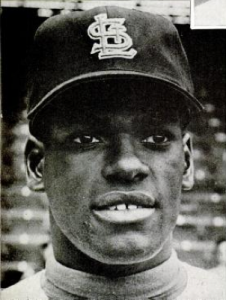

St. Louis Cardinal great right-hander Bob Gibson won 251 games over the course of a 17-year major league career and is in the Hall of Fame, deservedly so. (To put this in perspective, if a pitcher can last long enough to win 100 games as a major league player, he has achieved something significant in his profession, even though he would not be within smelling distance of the Hall of Fame.) Lefthander Tommy John won 288 games in a 26-year career (astonishing longevity for a ball player). He has a surgical procedure named after him that involves replacing damaged ligaments in a pitching elbow that prolonged not only his career (he was the first), but that of countless other pitchers, but he is not in the Hall of Fame. It is not simply how many games a pitcher wins or how long a pitcher hangs around, but how and where a pitcher wins his games. Lefthander Sandy Koufax never came close to winning even 200 games in a 12-year career (300 wins is a sure ticket to the Hall), had only four extraordinary years as a pitcher (but so extraordinary that they were unimaginable and largely unattainable for mere mortal players), retired at the age of 30, and is in the Hall. To get into the Hall, a pitcher must be more than durable and solid, competitive and competent. He must have pitched games where he prevailed in ways that were simply spectacular. John, who never won a Cy Young Award (given annually to the two best pitchers in the majors, the best in the National League and in the American League) or a Most Valuable Player Award, was never a dominant pitcher in the way Koufax and Gibson were in their primes. Koufax won Cy Young Awards and the Most Valuable Player Award, as did Gibson. And in one year in particular—1968—Gibson, with a 1.12 earned run average, the best ever recorded by a pitcher in the modern baseball era (since 1920), and 13 shutouts, two more than Koufax ever had in any single year, might have been the best pitcher there ever was. (Earned run average, or ERA, is the number of runs a pitcher allows every nine innings. Earned runs are runs that result from hits or walks and count against a pitcher’s earned run average. Unearned runs result from fielding errors and do count against a pitcher’s ERA. To have an ERA of slightly better than one run per nine innings after having thrown more than 300 innings in a season is so fantastically good as to be outlandish, utterly absurd, almost impossible.)

“ … I truly believed that nobody pitched better than I did in 1968, and the passage of time has thrown a favorable light upon the numbers. In recent years, I’ve read articles in which the case has been made that my season was the best a pitcher ever had. I’m not the proper authority to make that call and I don’t know what other pitchers from other years bring to the table, but I will say this much: I had my shit together in 1968.”

—Bob Gibson, Stranger to the Game: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson[iii] (emphasis Gibson)

Pitch by Pitch is Gibson’s account of the first game of the 1968 World Series that pitted the Cardinals, the National League champions, against the Detroit Tigers, the American League champions. (Nineteen sixty-eight was the last year that the major leagues were not divided into divisions that necessitated a playoff system. In 1968, as in all previous years, the two teams with the best records in their respective leagues after the end of the regular season played each other in the World Series.) Nineteen sixty-eight was also the year of the pitcher, when pitchers so overpowered hitters that baseball owners reduce the height of the pitching mound and changed the strike zone before the start of the next season. Denny McLain, the ace pitcher for the Tigers, won 31 games in 1968, a feat no pitcher is likely ever to do again as starting rotations are five deep instead as they were in the late 1960s and starting pitchers routinely pitched more innings 50 years ago as they threw more complete games; that is, pitching the entire nine innings, a rarity in today’s baseball. (Ironically, the last pitcher before McLain to win 30 games in a season was the Cardinals’ Dizzy Dean in 1934.) The first game of the Series featured a dream pitching match-up of Gibson, the best pitcher in the National League, versus McLain, the best pitcher in the American League. Both would win the Cy Young and Most Valuable Player Awards that year. Gibson lived up to his part of the bargain, throwing one of the best games ever in a World Series, striking out 17 Tigers, which is still the record for the most strikeouts in a World Series game by a starting pitcher. McLain, an amateur organist, airplane pilot, and hardcore self-promoter, who could consume nearly a case of Pepsi in a day, was mediocre, giving up three runs in five innings. McLain got the last laugh, as the Tigers won the Series in seven games.

Pitch by Pitch is exactly what its title states: Gibson describes the first game of the World Series by recounting every pitch he threw in the game and why he threw it. (He also analyzes every pitch McLain and the opposition threw as well.) It is as detailed an account as a reader can ever get of how strenuous pitching is: (“I’d drag my right foot so violently after my delivery that the joint in my big toe would swell up, skin would scrap off, and my sock would soak up blood.” “I never refrained from grunting like a female tennis player when I pushed off the rubber. Many times, after a game, my throat would be sore from grunting so much and so hard.”) But the reader is also reminded of how much thinking goes into pitching, despite its highly mechanical nature, how much the pitcher and the hitter are engaged in a game of wits. The pitcher is trying to control or, better put, exploit, three distinct dimensions: height, by varying low pitches with high pitches; width, by varying inside pitches that go toward the batter’s body with outside pitches that move away from the batter; and speed, by throwing some pitches harder than others. If the pitcher does this correctly, exploits these dimensions well, he keeps the batter off-balance, making it nearly impossible to hit the ball well. Batting is all about timing. Pitching is all about disrupting timing. The Tigers thought that Gibson threw the ball so well at Busch Stadium on October 2, 1968, that they conceded they never had a chance to win the game.

Why Bob Gibson was always angry

“ … I pitched better angry.”

—Bob Gibson, Stranger to the Game: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson[iv]

But there is more to the book than just the technical and graphic account of pitching: Gibson also talks his relationship with his teammates, how he felt about the opposing players, the particular day itself, and his own obsession with winning no matter the cost. A good deal of what is told here—his friendship with Cardinal catcher Tim McCarver, the unique camaraderie of the 1968 Cardinals, how manager Johnny Keane got his career on track—can be found in Gibson’s Stranger to the Game, his first-rate autobiography that served as sequel to his first book, From Ghetto to Glory: The Story of Bob Gibson, published in 1968. But there is some fresh stuff: his account of driving to Cooperstown with the Tigers’ Al Kaline after both men retired, his respect for Tigers’ outfielder Willie Horton, his account of pitcher Tracy Stallard’s dustup with Cardinals’ announcer Harry Caray.

“The day of the first game [of the 1968 World Series] there was a civil rights rally of some sort under the arch, which was a fairly common thing in those times and no particular concern of mine until I arrived at the stadium and a television reporter inquired if he could ask me a couple of questions. I said, ‘Sure,’ presuming he was going to talk about Horton or [Tiger first baseman Norm] Cash or McLain. Instead, he said, ‘What do you think of the black people demonstrating under the arch?’ I stared at him for a second and said, ‘I don’t give a fuck. I’ve got a ballgame to pitch.’ I don’t believe the interview made the air.”

—Bob Gibson, Stranger to the Game: The Autobiography of Bob Gibson[v]

Gibson was a snarly, driven, uncompromising performer on the mound. His catchers were afraid to come out to talk to him during the course of a game. His opponents, who were also afraid to approach him, swore he wanted to hit them with pitches, or that he did not, in the least, mind if he did so. Gibson always thought that if a batter was struck by a pitch it was the batter’s fault, and it was not Gibson’s job to feel sorry for them. He was an intimidator. In his prime, his attitude was something like that of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s killer cyborg in the first Terminator film. He was right: his pitching was fueled by anger. He was one of the most famous angry black men of his day but as he made clear, “I regarded myself as a ballplayer with a personal point of view, not an activist with a fastball. My idea of clubhouse ideology was the button I stuck over my locker before the series. It said, I’M NOT PREJUDICED. I HATE EVERYBODY.”[vi]

Bob Gibson’s opponents, who were also afraid to approach him, swore he wanted to hit them with pitches, or at least that he did not, in the least, mind if he did so. He was an intimidator. In his prime, his attitude was something like that of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s killer cyborg in the first Terminator film.

His anger, his curmudgeonly, surly nature was meant to fight his fear as it inspired fear in others. No high-performance athlete who desires success in competition can afford to feel fear. Fear eats confidence and without confidence a high-performance athlete will never succeed. Anger blocks fear very well. Yet, in 1968, Gibson’s angry was not just his extreme competitive passion but also a reflection of the time, of the turbulence of the urban riots and the civil rights movement and of the white backlash that ensued. As he writes in Pitch by Pitch, “RFK’s murder [New York Senator Robert Kennedy, brother of John Kennedy, was assassinated on June 5, 1968 in California], coming two months after Dr. King’s, hardened me. The slaying of Dr. King had touched me—and [Curt] Flood and [Lou] Brock and [Roberto] Clemente [black players who refused to play on the day of King’s funeral, April 9] and millions of others across the country—on so many levels that anger competed against a squall of other emotions. This was different. … [The] anger rose to the top. At least for me.” Gibson’s anger was complex, stemming from the inescapable strife of surviving as a professional athlete and the contradiction of being a successful black man who, nonetheless, needed the protection of the FBI when he received death threats after the death of King. Gibson also felt pressure as many black athletes became increasingly radicalized in the 1960s, led by heavyweight boxing champion Muhammad Ali and his opposition to being drafted by the army. The question that the television reporter asked Gibson annoyed him particularly because for Gibson it made him aware of the additional burden of being a black athlete at that time. Being asked such a question (his white teammates would never have been asked a comparable question about, say, anti-Vietnam War protest at the arch), implicated him as a spokesperson for his people, so to speak. He was also angry that the protest was even necessary, because blacks still had to protest in order to get ahead in the society. His was the unique anger of the privileged black man, the celebrated black star, who was permitted inside but remained an outsider.

If one wants to understand Bob Gibson the pitcher and technical craftsman, Pitch by Pitch is a good book to read. But Pitch by Pitch is fundamentally an inside baseball book, an ardent fan’s book. If one wants to understand Bob Gibson the man, Stranger to the Game is the better option.