Campaigns, especially presidential ones, are filled with fear, terror, giant egos, and small men.

—Craig Shirley, Reagan Rising: The Decisive Years, 1976-1980¹

1. The Interview with No Answers

On November 4, 1979, CBS aired a one-hour special entitled Teddy, a profile of the Massachusetts senator and the last surviving brother of the Kennedy clan. It is commonly thought that this program finished off Kennedy’s 1980 presidential run before it even officially began. Kennedy was surprisingly defensive, occasionally unengaged, and frequently inarticulate when Roger Mudd questioned him. The answer that everyone thought really did Kennedy in was when Mudd asked, “Why do you want to be president?”

“Well, I’m … uhh … were I to make the announcement … to run … the reasons that I would run is because I have a great belief in this country that is, it has more natural resources than any nation of the world, has the greatest educated population in the world the greatest technology of any country in the world, the greatest capacity for innovation in the world, and the greatest political system in the world.”

He stumbled on from that opening, although as he got going he stammered less and developed a bit of a cadence. The stammering would return as he continued his answer. He probably should have quit with the opening. As answers go, it was not good but hardly fatal. Kennedy would not be the first candidate, nor the last, to spew Casey Stengelese as a form of a non-answer. (Eisenhower was known to do this on occasion.)

If the night of July 18, 1969, had not happened, most Americans would have been willing to give Ted Kennedy the presidency almost by acclamation whether or not he wanted it, if only to alleviate our collective guilt over the deaths of his brothers.

Kennedy would argue in his autobiography that Mudd’s interview was a set-up, an ambush, that he was under the impression that the interview was going to be entirely different. Kennedy had not announced that he was running for president and would not do so until November 7, so the question was unexpected and unfair. Mudd, of course, begged to differ about how the interview was pitched to Kennedy. It scarcely matters. What is surprising is why Kennedy attempted to answer the question at all. He could have simply said: “I will explain why I want to be president when and if I announce that I am running.” Sometimes, I suppose, even the most practiced public figures, and Kennedy was surely one of them, can be utterly flummoxed by a simple question, so flummoxed that they forget the cardinal privilege of the public figure: being under no obligation to answer a question that you do not want to answer.

I do not think most people, whether they liked or hated him, cared whether he had a good reason or no reason at all for running. Kennedy had a special connection to the presidency, was entitled to aspire for it, to want it, as most of the public thought, because one of his brothers was murdered while having the job and another was murdered while campaigning to get the job. If the night of July 18, 1969, had not happened, most Americans would have been willing to give Ted Kennedy the presidency almost by acclamation whether or not he wanted it, if only to alleviate our collective guilt over the deaths of his brothers.

But it was what happened on that night in July, about which Mudd sharply questioned Kennedy and where Kennedy’s answers about “the conduct” remained as doubtful as ever, that ruined his chances for the presidency. As Jon Ward writes in Camelot’s End, “What has gone unremembered is that by the time Kennedy fumbled Mudd’s most famous question, the damage had already been done.” (158) On that night, Kennedy drove his black Oldsmobile off the Dike Bridge into Poucha Pond on the tiny island of Chappaquiddick. Kennedy managed to save himself but his passenger, 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne, a Democratic political operative, one of the “Boiler Room Girls,” as they were called, drowned. Kennedy did not report the accident until ten hours after it happened. As the years went by, more people became skeptical of Kennedy’s account of the accident. People who hated him, and there were legions who despised the Kennedys, crucified him with it or tried to. (It should be remembered that Kennedy himself was nearly killed in a small plane crash in 1964, spending months recovering from his injuries. Who knows what effect that had on him?)

In effect, Kennedy, when he chose to run for his party’s presidential nomination in 1980, was really a dead man walking. What is interesting is that the man Kennedy challenged, incumbent Jimmy Carter, was also a dead man walking.

Chappaquiddick’s negative impact on Kennedy’s presidential prospects was instantaneous, so much so that his sister, Eunice, had to talk him out of vowing never to run for the presidency when he gave his televised speech apologizing for the incident. “His dead father and his martyred brothers,” Ward writes, “would hover over him until he fulfilled his destiny.” (70)

In effect, Kennedy, when he chose to run for his party’s presidential nomination in 1980, was really a dead man walking. What is interesting is that the man Kennedy challenged, incumbent Jimmy Carter, was also a dead man walking. Why did Kennedy choose this moment to run, to challenge his party’s incumbent, something almost unheard of in modern presidential politics? Why did he not run in 1972 or 1976 when the Democrats had no incumbent? (Some can recall former president Teddy Roosevelt challenging incumbent William Howard Taft in 1912 and how that turned out for the Republicans.) The challenge so damaged the Democrats that it took them twelve years to recover from it. Republican nominee Ronald Reagan beat Carter by a landslide, winning 489 of 538 electoral votes and capturing 50.7 percent of the vote to Carter’s 41 percent. Carter may have lost without Kennedy’s challenge but the challenge nearly assured it.

2. The Race with No Winner

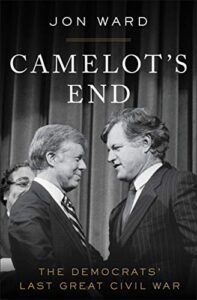

Camelot’s End, the title referring to John F. Kennedy’s presidency being characterized as Camelot, a storied time in American politics and largely a myth that John’s wife, Jacqueline, especially promoted after Kennedy’s assassination in 1963, tells the story of the 1980 Democratic presidential primaries, where Ted Kennedy challenged sitting president Jimmy Carter. It makes for a good story, the two men offering such rich contrasts.

Carter was the son of a hard-working Georgia peanut farmer who wound up a graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy and ultimately a submarine officer before returning to Georgia as a civilian after his father’s death, taking charge of the family peanut farm and eventually entering politics and becoming a born again Christian. Kennedy was the privileged youngest son of a rich Irish Catholic Massachusetts businessman and ambassador, Joseph Kennedy, who had great ambitions for his children. His eldest son, Joseph Jr., was killed in combat during World War II. John, senator and president, and Robert, U.S. attorney general and senator, were both the victims of violent political murder in the 1960s. Unlike Carter, who seemed sure about what he wanted to do and driven to get there, Kennedy was less certain, obscured by his more famous and more talented brothers, kicked out of Harvard for cheating (he was later readmitted), tormented by whether he could live a serious life. There was always the sense that Ted was a disappointment, not only to his father, but in some measure, to himself. Dumb, chunky Ted, the poor little rich kid! Becoming president had to be a burden to him, at least most commentators thought so. They also thought his answer to Mudd’s question about running was so inadequate because he did not want the job and subconsciously did not really want to win. That may or may not be true. What seems clearly true from Camelot’s End is that he certainly wanted Carter to lose.

Kennedy felt Carter was not liberal enough and particularly felt that his signature issue of national health care was being ignored. So, the faux redeemer versus the scarred reprobate was engaged. It was a contest to see how small each man could make the other appear to be.

Carter met Kennedy while Carter was governor of Georgia (1971-1975) and the two men instantly disliked each other. Kennedy, the star of the Democratic Party, treated Carter as if he were Mr. Nobody from Nowhere. Carter, for his part, chose to steal Kennedy’s thunder in the speech he gave for the occasion of Kennedy’s visit, wanting Kennedy to understand that he was not about to be pushed around by the famous northern politician from the rich, storied family. Carter had been seriously thinking about a presidential run since 1972 and felt Kennedy to be his most serious rival. Carter, on some excuse, would not let Kennedy spend the night at the governor’s mansion. Kennedy would return the humiliation in spades on the night that Carter accepted the nomination at the Democratic convention by arriving for the raised unity handshake late and then forgoing the gesture entirely, treating Carter’s coronation as if he were attending the wedding of his chauffeur. (272) He also refused to campaign for Carter unless Carter paid Kennedy’s campaign debts.

Kennedy did not run in 1976 because of his son’s bout with cancer. In 1980, Kennedy, disappointed and exasperated by Carter’s failed leadership and seemingly fumbling presidency, challenged him, although he knew the odds were long that he could beat a sitting president, even a bad one. Kennedy felt Carter was not liberal enough and particularly felt that his signature issue of national health care was being ignored. So, the faux redeemer versus the scarred reprobate was engaged. It was a contest to see how small each man could make the other appear to be.

Carter gave the impression of being pious, open, innovative, caring, and even gentle in some respects. But he was a tough, even ruthless, determined, hard-working politician who understood the trappings of power and how to use power and organization to crush his opponents. He won the presidency by being a new type of southerner, progressive on race, a technocrat, thoroughly modern, not someone harkening back to some romanticized order of privilege. (Bill Clinton would use a modified version of the Carter-esque southerner when he ran in 1992.) Carter’s appointment of Andrew Young as his ambassador to the U.N. was controversial and, at the time, path-breaking, though in the end not especially successful. More than anything, Carter’s “myopic, obsessive managerial style” would contribute greatly to his undoing. (112)

Carter gave the impression of being pious, open, innovative, caring, and even gentle in some respects. But he was a tough, even ruthless, determined, hard-working politician who understood the trappings of power and how to use power and organization to crush his opponents.

The three biggest challenges for Carter were high inflation (double-digit), a hostage crisis in which Islamic militants in Iran held fifty-two American diplomats (which dragged on for months and even featured a failed rescue attempt), and the gasoline shortage (which produced lines at gas stations and even violence). The issues seemed larger than Carter’s capabilities. Carter’s approval rating at one point fell to 19 percent, the lowest of any president in the modern era. (He did manage to recover.) This, Kennedy tried to exploit but did not figure on the powerful Carter machine, the fact that, for a time, Carter’s Rose Garden approach to governing worked, and the still lingering public concerns of Chappaquiddick; in addition, Kennedy’s old-fashioned progressivism was simply out of step with the mood of the country. Reagan, despite his own bumbling and superficial rhetoric, was able to exploit public despair over the country’s problems much better. Reagan, the conservative, measured and responded to the country’s mood much better than any liberal of the time.

Camelot’s End is not a scholarly book. But it is a solid, journalistic account of an important moment in the history of the Democratic Party and the United States.