Stacey Dash, a minor African American actress, came to the attention of the general public in 2012 in a far more theatrical way than her professional acting ever offered when she tweeted her support for Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney:

Vote for Romney. The only choice for your future. @mittromney @teamromney #mittromney #VOTE #voteromney

Dash’s claim to fame before this tweet was that she had a supporting role in the highly successful 1995 movie comedy, Clueless, a role she continued to play in the television series the movie spawned. She also appeared in an episode of The Cosby Show and had supporting roles in Moving (1988 with Richard Pryor) and Mo’ Money (1992 with Damon Wayans). This is a career that is the equivalent of a back-bencher’s in politics.

There are two reasons why her tweet supporting Romney was such a splash, so much so that it struck some as being self-serving: first, African Americans make up a tiny portion of the Republican Party’s base of support; second, Obama was running for re-election. She had voted for Obama in 2008. She had been, as she put it, “blacked” into it. By this I suppose she meant that she voted for Obama out of sense of racial pride and a kind of race “group pressure.” Had not Obama, but rather a white Democratic candidate, been running in 2012, she might have been dismissed by other blacks as a bush-league apostate but Obama upped the ante of race traitor-dom exponentially. There was simply too much at stake for most African Americans not to vote for Obama’s re-election, in some ways more at stake than when he initially ran. In many quarters, especially among African Americans, it nearly goes without saying, Dash was excoriated for the tweet. She seemed to have anticipated this as she went to church to ask God whether she should send it. Indeed, she may have wanted this response as an aging actress with few career options could get more publicity supporting Romney than she could tweeting that she supported Obama. And in her profession, as the old saying goes, there is no such thing as bad publicity. Some will say that she outed herself as a conservative for this very reason. Perhaps. But it seems too conveniently cynical to dismiss black conservatives by discrediting their sincerity. Is not everyone a political animal, if one chooses to be political, in order to get something out of it: money, influence, policy advantages which might be better than money, the psychological pleasure of vanquishing one’s political foes (or the pure satisfaction of being able to hate in a socially-sanctioned way), the approval of one’s friends and acquaintances or of the people in power in one’s profession.

She writes that she had “grown so tired of President Obama’s shtick.” She continued: “He couldn’t even make good on his promise to cause America to ‘come together.’ We were more divided, angrier, and more partisan than I’ve seen in my lifetime. In fact, since Obama had taken office, suddenly everything was about race.” In some respects this is true and, because Obama is a liberal, it was inevitable, although no one could see this in 2008. Many who opposed Obama resented his race because they felt he won the office simply because he was black (and handsome and articulate). His victory, which they felt to be a form of reverse discrimination, simply sharpened their dislike of him because of his race. (It might be accurately said that many whites who voted for Obama did so out of impulse of romantic racialism [1], a not uncommon affliction in this country.) So, many of Obama’s enemies were moved to despise him because of his race. For his part, Obama, as a capable politician, and his minions would move, directly and subtly, to discredit all criticism of him was being driven by racism. This combination spiked the volatile witches’ brew of race relations in this country in ways that deepened racial resentments rather than mollified them. Obama was thus a fitting president for his generation. He became ironic.

‘The school of hard knocks tends to teach you lessons in conservatism,’ Dash writes, although it might be just as likely that such a school would radicalize or criminalize you in lessons of resistance and rebellion. I suppose it is a matter of what you will hate more: the system that put you in this situation or the people with whom you find yourself. One will make you a radical; the other a conservative. Either may make you a success, albeit in very different ways.

Dash gives us a generous sample of the insulting responses her tweet generated. She was taken to task by hip-hop mogul Russell Simmons, but defended by Whoopi Goldberg. Vice presidential candidate Paul Ryan called her to express his appreciation for her support, calling her “brave.” She does admit to the truth of some of the tweets that said she was “‘washed up’ and irrelevant.” “They weren’t far from the truth.” She goes on to say she made “a few bad decisions. Actually a lot of bad decisions, almost all because of men.” The book provides us with more information about her love life and failed marriages than a book published by Regnery, one of the leading conservative publishing houses in the country, would normally have. But I suppose one must make a few compromises when dealing with Hollywood types.

Dash grew up in the South Bronx, the offspring of two drug-addicted parents, saw her first dead body when she was 3 years old, walking by herself to preschool. “The school of hard knocks tends to teach you lessons in conservatism,” she writes, although it might be just as likely that such a school would radicalize or criminalize you in lessons of resistance and rebellion. I suppose it is a matter of what you will hate more: the system that put you in this situation or the people with whom you find yourself. One will make you a radical; the other a conservative. Either may make you a success, albeit in very different ways.

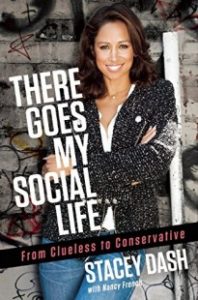

The title of Dash’s book is a slight paraphrase of a funny, if highly salacious, response she gives a character in Clueless who, refusing to participate in a physical education class, says, “My plastic surgeon says to avoid activities where balls fly at your face.” Dash’s character retorts, “There goes your social life.” The title of her book implies the cost of coming out as a Republican in Hollywood: “Dare you speak out about a hotly contested presidential election? When you’re black? When you’re an actress? When you’re a woman? There goes your social life.” (italics Dash)

Dash argues: “We have all the opportunities we could ever need. All we have to do is walk in them. Black, White, Hispanic, Asian—whatever your color and whatever your ethnic background—no one is keeping you down in America but you. Well, you and the Democratic Party that wants to manipulate your vote.” This is a highly debatable point, to say the least. But if the Democratic Party is manipulating blacks by exacerbating their unhappiness, why can it not be said that the conservatives of the Republican Party are manipulating you by telling you that you really have nothing to be unhappy about because the world has now become your oyster.

Dash’s book alternates between personal narrative—an account of her growing up rebellious in a tough environment with wayward parents who changed her schools frequently, stumbling into show business (although never, by this book’s exposition, formally studying acting or mastering her craft), and falling in and out of a series of abusive relationships with men—and little conservative op-eds (probably the main contribution of her co-writer) that provide a political interpretation of these life passages. When she is pregnant with her first child and threatens an abortion, indeed, gets to the point of going to the abortion clinic to have the procedure before melodramatically pulling her IV line from her wrist when the light dawns, the reader is then given the anti-abortion op-ed. There is nothing wrong with these interludes about school choice, gun rights, sex outside marriage, and the virtues of free market capitalism. They are standard conservative fare and highly debatable, but they do competently summarize the conservative position and Dash and her co-writer adroitly use Dash’s life to illustrate or underscore these points.

But on the whole Dash’s book feels superficial and unreflective, despite all details about her sex life. There is a lack of introspection here, even a lack of certain kind of self-awareness. Dash thinks that she can see outside herself because she has placed herself outside of the mainstream of her racial group by being a conservative Republican. But this move has given her distance, not perspective. The book feels defensive. There are moments in the book, for instance, when she talks about black women’s hair, or the struggles of rearing her children, or actually working an acting job, that the reader wishes she would explore more deeply and with greater nuance. Dash is clearly an intelligent woman, even, in some respects, an admirable one. Her transition to conservatism may be hustle to survive or it may be a way for her to assert control over her life, to try to define her life on her terms, her way of saying being black is how I wish to see it, not how others wish for me to see it or are trying to see it for me. This could have been a much more powerful examination of the meaning of pushing oneself against the group, but it seems to have chosen the easiest and most obvious way to exploit its subject.