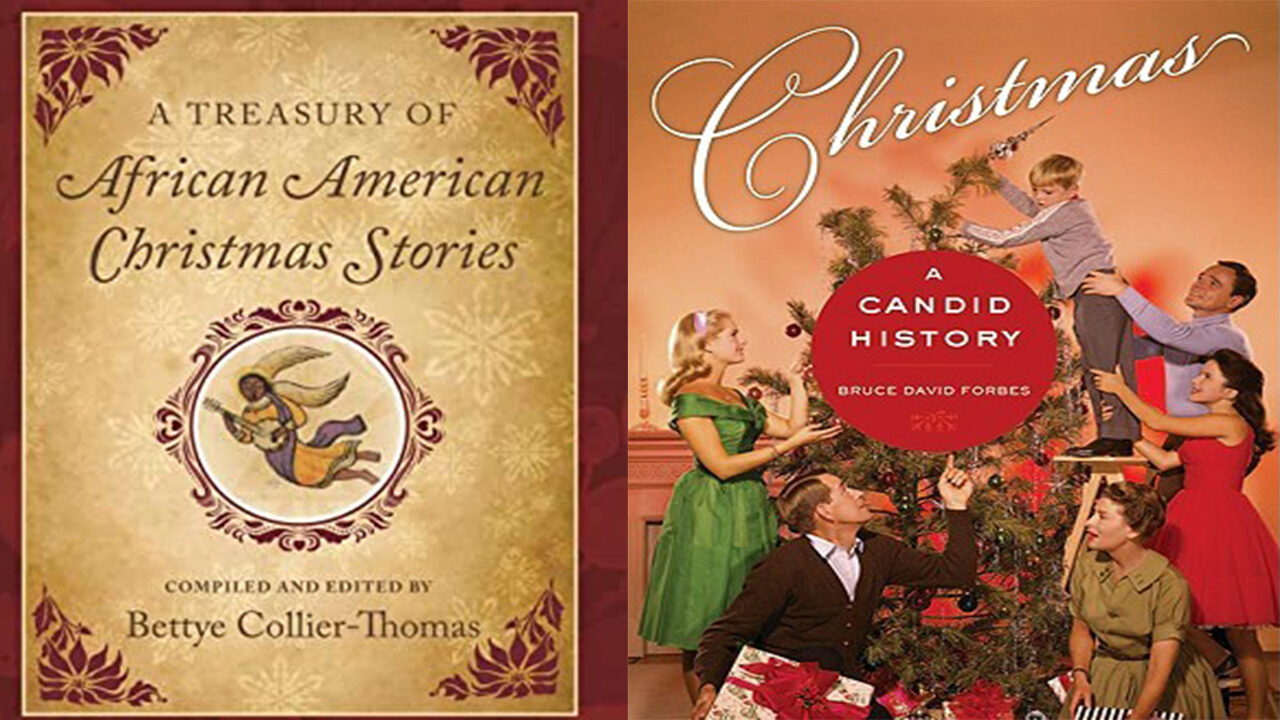

A Treasury of African American Christmas Stories

Compiled and edited by Bettye Collier-Thomas

(2018, Beacon Press) 228 pages with a list of sources

Christmas: A Candid History

By Bruce David Forbes

(2007, University of California Press) 179 pages with index, bibliography, and notes

1. Christmas of Color

“I’m dreaming of a white Christmas”

—Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas”

A Treasury of African American Christmas Stories is the third iteration of Bettye Collier-Thomas’s anthology of Christmas stories by Black American writers. It might be called a “best of,” as Collier-Thomas writes in her introduction: “This book, as a compilation of the best stories in the first two volumes, plus five additional stories and narrative poems, includes writings from the earliest period [1880-1920] to 1953.” (xiv) Christmas has always had considerable significance for Black Americans since the days of their enslavement. Whatever the holiday may have meant as a religious celebration of the birth of the Christ child, it had practical relevance for the enslaved: it meant no work for several days. Most plantations relaxed the regimen of slavery between Christmas and New Year. Slaves were given free time to be with family and friends, were given extra rations of food, and were permitted to eke out their diets with hunting and fishing. They were usually given gifts from their owners. Sometimes, the rowdiest time on plantations was Christmas, as slaves were often given liquor then too.

There was in the old European tradition of winter festivals role reversal where men became women and women men for a night and where the landowners and master-class permitted the underlings and servants to be sort of pseudo masters for a day and the powerful became the servants in a sort of Jean Genet-esque fantasy of exchange and equality. Bruce David Forbes describes this briefly in Christmas: A Candid History. (8-10) There is much greater detail about it in Stephen Nissenbaum’s The Battle for Christmas (Knopf, 1996). This practice did not carry over to the American slave south for obvious reasons during the Christmas season. The planters felt there was no need to encourage dangerous ideas through cosplay. But this practice does reveal how significant identity was in these festival celebrations.

In his 1845 Narrative, Frederick Douglass gives one of the most famous, detailed, if disapproving, descriptions of the Christmas holiday in the 1830s for plantation slaves:

“The days between Christmas and New Year’s day are allowed as holidays; and, accordingly, we were not required to perform any labor, more than to feed and take care of the stock. This time we regarded as our own, by the grace of our masters; and we therefore used or abused it nearly as we pleased. Those of us who had families at a distance, were generally allowed to spend the whole six days in their society. This time, however, was spent in various ways. The staid, sober, thinking and industrious ones of our number would employ themselves in making corn-brooms, mats, horse-collars, and baskets; and another class of us would spend the time in hunting opossums, hares, and coons. But by far the larger part engaged in such sports and merriments as playing ball, wrestling, running foot-races, fiddling, dancing, and drinking whisky; and this latter mode of spending the time was by far the most agreeable to the feelings of our masters. . . .

From what I know of the effect of these holidays upon the slave, I believe them to be among the most effective means in the hands of the slaveholder in keeping down the spirit of insurrection. Were the slaveholders at once to abandon this practice, I have not the slightest doubt it would lead to an immediate insurrection among the slaves. These holidays serve as conductors, or safety-valves, to carry off the rebellious spirit of enslaved humanity. . . .

The holidays are part and parcel of the gross fraud, wrong, and inhumanity of slavery. They are professedly a custom established by the benevolence of the slaveholders; but I undertake to say, it is the result of selfishness, and one of the grossest frauds committed upon the down-trodden slave.”

What Douglass asserts is that the planters used Christmas as a form of social and psychological control; it was a kind of self-serving benevolence. Note that nowhere in Douglass’s description does he mention the birth of Christ or the planters emphasizing or even mentioning the religious importance of Christmas.

There are three observations to make about Douglass’s description: first, because southern planters were not from a Puritan or Dissenting tradition, which were strongly anti-Christmas, they tended the follow the custom of Christmas in Europe that included bountiful food and drink, masters and lords providing gifts for their workers and serfs, and a general time of frolic and release. As Forbes points out in Christmas: A Candid History, Christmas grew from the pagan European traditions of Saturnalia (Ancient Rome) and Yule (northern Europe), winter festivals where excessive partying, eating, sensuality, having a good time were meant to cast off the gloom of winter. (7-13) In some ways, the slave’s Christmas was meant to encourage behavior that momentarily cast off the gloom of slavery, that existential winter of imprisonment. Occurring during the plantation’s winter season, the holiday was an attempt to make winter and slavery more bearable. But there is no reason to think that the planters’ celebration of Christmas differed greatly from the enslaved’s as a form of revelry and indulgence. There was more food on a plantation at Christmas, as a result of harvests, than any other time of year and it was a time of the least work, as the cycle of agrarian tasks was at its lowest ebb for the winter. It was a time when the planters could momentarily feel less pressure too about running the plantation for profit.

Second, Christmas was always meant to be, in some ways, a form of social control. As Forbes writes, “Some way or another, Christmas was started [under Constantine] to compete with rival Roman religions, or to co-opt the winter celebrations [such as Saturnalia and Yule] as a way to spread Christianity, or to baptize the winter festivals with Christian meaning in an effort to limit their excesses. Most likely, it was all three.” (30) In short, the Christmas movement, as it were, in the early Christian church was meant to influence people’s behavior and to shape their thinking; it was a form of cultural and social engineering to re-orient people about the meaning and symbols of their play, and the meaning of nature. Southern planters were working within a tradition in how they used Christmas to shape the behavior and thinking of their slaves.

In some ways, the slave’s Christmas was meant to encourage behavior that momentarily cast off the gloom of slavery, that existential winter of imprisonment. Occurring during the plantation’s winter season, the holiday was an attempt to make winter and slavery more bearable.

But what is most important about Douglass’s description is that he experienced Christmas on the plantation in the 1830s at a time when the invention and revival of Christmas was beginning in earnest in the United States. Forbes recounts the 1823 publication of Clement Moore’s (or Henry Livington’s) “The Night Before Christmas,” the most famous poem ever written by an American, which established the gift-giving Santa Claus, riding on a sleigh driven by reindeer, coming down chimneys on Christmas Eve night. (84-90) Queen Victoria took the English throne in 1837 and became one of the promoters of Christmas, importing the Christmas tree from Germany, and emphasizing it as a time for family. Later, Sarah J. Hale, editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, the most important woman’s magazine in the United States, not only pushed for a national Thanksgiving holiday but encouraged Christmas as well through the publication of illustrations of Christmas trees. (63-66) Christmas was starting its crest as a national holiday with considerable semi-secular references such as Santa Claus and Christmas trees. Southern planters were not immune to the emotional and psychological impact of this rapidly emerging holiday themselves, so it is hardly surprising that they wanted to shape this cultural phenomenon for their own political use. For Douglass, Christmas for the enslaved had not thrown off its moral and psychological corruption that the church had tried to cleanse when it attempted to absorb European winter festivals. It was a terrible holiday. As historian Stephen Nissenbaum so aptly put it, “. . . Christmas has always been an extremely difficult holiday to Christianize.” (Quoted in Forbes, 32)

Nonetheless, despite Douglass’s view, most enslaved Black Americans had good memories of Christmas and very much looked forward to it every year. A survey of the collections of oral slave narratives is proof of this. It was, in the quotidian realm, a break from work and stress, but the religious meaning of the holiday was appealing too, even if Douglass neglects to consider it at all in his description of the plantation Christmas. The enslaved identified with the lowly birth of the savior, the tradition that one of the wise men (or kings) was Black, the fact that Mary and Joseph had to flee to Egypt to escape Herod’s hunt for the child. The perils and circumstances of Jesus’ birth, as the myth developed, made him seem, well, for lack of a better description, a bit like a Black child and his parents, running from persecution.

But it is clear that Black Americans have had to wrestle with Christmas. The creation in 1966 of Kwanzaa, the Black holiday that starts the day after Christmas, an Identity holiday that is meant to celebrate family, children, generosity, and a romanticized, uncomplicated African past, indeed, all the things that Christmas celebrates, is part of that wrestling. For Kwanzaa was created because Christmas lacked something for at least some Black Americans, that it was not truly their own holiday. Kwanzaa has been a way to counter whatever political significance that Whites have placed on the holiday with their own political significance and their own vision of nature.

The enslaved identified with the lowly birth of the savior, the tradition that one of the wise men (or kings) was Black, the fact that Mary and Joseph had to flee to Egypt to escape Herod’s hunt for the child. The perils and circumstances of Jesus’ birth, as the myth developed, made him seem, well, for lack of a better description, a bit like a Black child and his parents, running from persecution.

For Black Americans, the questions might be asked, what does Christmas mean to us? And how can we make Christmas something usable for us? If, as Douglass argues, Christmas was tainted by the power politics of slavery, as the stories in Collier-Thomas’s collection make clear, it was equally tainted by Jim Crow and segregation. Christmas in America, in short, was tainted by racism. So, why then did Black writers try to create a practice, a lineage of writing about Christmas? To rescue it for themselves? Or through saving it for themselves to save for the nation?

2. “I often wonder what the Wine-Merchants buy/One-half so precious as the goods they sell

. . . just like the ones I used to know.”

—Irving Berlin’s “White Christmas”

From a purely literary perspective, there is only one good story in Collier-Thomas’s collection, Langston Hughes’s “One Christmas Eve,” about a Black boy who is out late with his overworked, harried, poorly paid mother in a Jim Crow American city and who wanders off by himself, goes into a White theater and meets Santa Claus there, someone he has been pestering his mother about. The White Santa, who is giving candy and cookies to the White children, scares him by shaking a rattling toy in his face, making him run out of the theater. After he explains what happens, his mother says, “‘That wasn’t no Santa Claus. If it was, he wouldn’t a-treated you like that. That’s a theatre for white folks—I told you once—and he’s just a (sic) old white man.’” (200) It is a touching and despairing story. Hughes is, without question, the best writer in the collection.

John Henrik Clarke’s famous “Santa Claus is a White Man” takes up the theme of a Black boy encountering a White Santa while out Christmas shopping with his mother. This time the Santa leads a mob of Whites who rob the boy and threaten to lynch him, a far more luridly violent story than Hughes’s, something like the sort of story Richard Wright wrote for his collection, Uncle Tom’s Children (1938). This too is a despairing story, but it lacks Hughes’s grace notes of humanity and love trying to raise over cynicism that Hughes offers in the depiction of the relation of the boy and his mother. Another, more hopeful story about a Black boy and Santa Claus is Valena Minor Williams’s “White Christmas.” Here, a Black boy, who is sick of seeing White Santas on street corners during Christmas, reluctantly joins his Uncle Charlie, a maître d’hôtel, who is working the Christmas festivities at the hotel. The White man who normally plays Santa is sick, and Charlie’s boss asks Charlie to play the part, wearing a White mask, which actually the White man who plays Santa wears. Charlie’s nephew, disappointed, thinks Charlie is “going to pass for a white Santa.” (223) But Charlie refuses to don the mask to play Santa and the nephew is proud that Charlie refused to succumb, working the festivities as a Black Santa. Clearly, one of the preoccupations of many of these stories is the contradictory idea of a White Santa who would give gifts to and care about Black children.

Nearly all the stories and poems in Collier-Thomas’s collection were written by Black journalists who wrote for Black publications. This means, of course, that the audience for these works were Black and the writers were quite conscious of writing for Blacks. It is unclear whether many of the stories were written for children, but it is almost a certainty that some were. This complicates the question of audience even more, if one considers that some of the stories were meant to be read by or to children. Many of the stories feature children, as one might expect in writing about Christmas. There is a great concern with downtrodden children (Alice Moore Dunbar’s “The Children’s Christmas” and Pauline Elizabeth Hopkins’s “General Washington: A Christmas Story”); racism and specifically lynching are condemned in Andrew Dobson’s phantasmagoric poem “The Devil Spends Christmas Eve in Dixie;” and the relationship between Black men and Black women and Christmas as a kind of epithalamic affirmation of Black coupling is explored in Bruce L. Reynolds’s “It Came to Pass: A Christmas Story” and Margaret Black’s humorous “A Christmas Party That Prevented a Split in the Church.” W. E. B. Du Bois offers a “the Baby Christ is Black” story, an idea that was and continues to be popular with many Black Americans. The theme of condemning the hypocrisy of America is common throughout the collection. With the exception of Du Bois, Alice Moore Dunbar (wife of poet/novelist Paul Laurence Dunbar), Hughes, Hopkins, and Clarke, the writers would be completely unknown to anyone except a literary historian specializing in Black American literature. Most of the stories would not be considered great literature but the stories are endlessly interesting and engaging, amazing cultural curios. This anthology is important because it permits readers to learn a bit about how Black people have thought about Christmas, their alienation from it, their attempts to embrace it, and their wish and hope to cleanse it of racism, to make it truly a holiday for all, to endow it with a cultural cosmopolitanism.

. . . how many of the emperors, popes, writers, political leaders, merchants, and cultural influencers who have given us Christmas as we know it today are especially admirable people? Some are, to be sure. But many are not. And if Kwanzaa seems lightweight culturally in comparison to the music, art, legends, practices, and theological density that now comprise Christmas, remember that Kwanzaa has existed for 60 years, and Christmas has developed over 1,500 years.

Forbes’s Christmas makes a nice complement to Collier-Thomas’s collection as it provides a short, highly accessible account of the history of the holiday. Kwanzaa has often been criticized as “a made-up holiday.” This is so. Kwanzaa is made-up, derivative, and superficial. Its founder is not an especially admirable person, a hustler, it might be said. But Forbes reminds us that in many respects, Christmas is a made-up holiday too: there is no biblical sanction for it. Its creation was a way for Christianity to spread the faith and stamp out paganism; when it was promoted and reinvented in the nineteenth century with Washington Irving, Charles Dickens, Clement Moore (or Henry Livingston), Thomas Nast, and Queen Victoria. Forbes makes the excellent point that none of this accrual of fabrications was led by the Church, nor was it connected to Jesus Christ, although these fabrications aided the Church and helped put fannies in the pews. Finally, how many of the emperors, popes, writers, political leaders, merchants, and cultural influencers who have given us Christmas as we know it today are especially admirable people? Some are, to be sure. But many are not. And if Kwanzaa seems lightweight culturally in comparison to the music, art, legends, practices, and theological density that now comprise Christmas, remember that Kwanzaa has existed for 60 years, and Christmas has developed over 1,500 years.

Christmas dramatizes cultural conflict: consumerism, acquisitiveness (particularly encouraged in children), fixation on the material, and overabundance versus generosity to strangers, charity to the needy, the gathering of family and friends, gift-giving, the glory of the birth of a child, the belief that in the birth of a child lies the redemption of the world. It can be argued that Christmas really would be more coherent as a holiday, that Americans would feel less conflicted about its opposing values if it dropped its rather precarious religious claims. It must be remembered that the Church had little to do with the promotion and creation of the holiday as we celebrate it now. (66) On the other hand, the tension between the Christian and the secular that so warps Christmas and threatens to wreck it is perhaps the very thing that gives it meaning and depth, that makes it matter. Christmas is such a perfect reflection of what we are, our deep flaws, and our ennobling aspirations. Forbes’s book helps us to understand how knowing Christmas provides a wider context to appreciate how Black Americans experience Christmas, which is so deeply connected to how they experience America.