Ask a Baby Boomer to name the Trial of the Century, and the immediate—and confident—answer will be the criminal trial of former football star O.J. Simpson on two counts of murder for the gruesome stabbings of his ex-wife Nicole and her friend Ron Goldman, whose corpses were found on the front steps of her condo. Beamed into millions of homes on television, the O.J. Simpson case generated virtually nonstop media coverage from opening statements in January 1995 through the controversial Not Guilty verdicts ten months later. For my generation, the term Dream Team evokes not the U.S. Olympic basketball team but O.J.’s team of defense lawyers, and the name Kardashian evokes not the sisters of reality TV infamy but their late father Robert, a member of that Dream Team. Ask one of us to complete the phrase, “If it does not fit,” and we will answer, “You must acquit.” And while we may have trouble naming the poet who wrote “Sailing to Byzantium,” we all know that it was Johnnie Cochran who recited that rhyming couplet in his closing argument. We may fumble over the name of the Supreme Court Justice who wrote the landmark opinion in Brown v Board of Education, but we Baby Boomers know that the presiding judge at the O.J. Simpson trial was Lance Ito.

And thus it may surprise my fellow Boomers to learn that our Trial of the Century is, at best, the trial of the decade—and one whose juicy details will be as little known to our grandchildren as the far juicier details of the Harry Thaw murder case of 1907 are known to us. Indeed, if gauged by the quantum of scandal, sex, fame, wealth, and flagrancy, the O.J. Simpson trial pales next to that prior Crime of the Century, in which the scion of a wealthy and prominent family drew his pistol in the crowded rooftop theater of Madison Square Garden, and, in a jealous rage, fatally shot the celebrated architect Stanford White over White’s alleged corruption of Thaw’s wife Evelyn, nicknamed by the press as “The Girl in the Red Velvet Swing,” which later became the name of the 1955 motion picture of those events, with Joan Collins in the title role.

And that first Trial of the Century was soon to be eclipsed by the Sacco and Vanzetti and the Leopold and Loeb trials of the 1920s, whose facts today are little known outside of university history departments. Indeed, perhaps the most sensational trial of that decade—whose newspaper coverage exceeded even that of the Titanic disaster and whose courtroom spectators including a daily carousel of national and international celebrities—was known to an enthralled nation as simply the Sash Weight Murder Trial and today is known mainly to readers of Bill Bryson’s One Summer: America, 1927 (Doubleday 2013). Other defendants in their era’s Trial of the Century have included Roscoe “Fatty” Arbunckle, Leo Frank, Bruno Hauptmann, the Scottsboro Boys, Dr. Sam Sheppard, Julius and Ethyl Rosenberg, and Charles Manson. The Scopes Monkey Trial, which featured a courtroom battle over Darwinian evolution between two legal heavyweights of their era—Clarence Darrow and William Jennings Bryan—has generated a library shelf worth of books, along with a play (1955) and a film (1960) entitled Inherit the Wind.

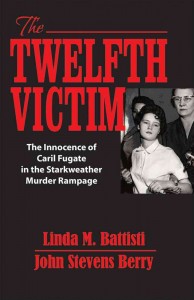

The Twelfth Victim arises out of a 1950s Crime of the Century known as the Starkweather Rampage. Its namesake, Charles Starkweather, was hardly a poster boy for, well, a Most Wanted poster. He was a short, red-headed, bow-legged, 19-year-old from Lincoln, Nebraska. Nevertheless, during the space of two months he murdered eleven people in Nebraska and Wyoming, terrified the citizens of those states, and horrified the nation. The murder spree ended with his arrest after a high-speed car chase in January of 1958.

we close the book frustrated by a sense of incompleteness, by a story that feels cut off in the middle. We want to know more about Caril Fugate’s life after that Trial of the Century, what it was like to come of age in prison, to re-enter society as an ex-con convicted of being an active accomplice to one of the most notorious murderers of the century.

His was the first trial following the Starkweather Rampage. He was convicted of all murder charges and sentenced to die in the electric chair—a sentence carried out a year later. The Twelfth Victim, however, focuses on the second Trial of the Century, where the defendant was Caril Ann Fugate, Starkweather’s 14-year-old girlfriend who was with him through most of the murder spree.

Was Caril really his accomplice in those eleven murders, whose victims included her mother, her stepfather, and her baby sister? She claimed she was Starkweather’s captive, too terrified to escape. She claimed that he told her that her family was alive and held hostage by a gang and that if she disobeyed him or tried to run away he would make one phone call to the gang leader that would result in the deaths of her family. She claimed that she didn’t discover her family was already dead until after the police arrested her.

Starkweather, however, who gave nine inconsistent and significantly conflicting versions of the key facts between the time of his arrest and his trial, took the stand in Caril’s trial and testified that she was his willing partner in the crimes. The jury found Caril guilty, and she was sentenced to life in prison. She is, in the authors’ telling of this disturbing tale, the twelfth victim of the Starkweather Rampage—a victim of prosecutorial misconduct from the moment of her arrest.

While many today have only the vaguest recall of the facts of the Starkweather Murder Rampage and the subsequent two Trials of the Century, over the past six decades the tale of Charles Starkweather and Caril Fugate has entered American culture in a variety of significant ways. In addition to numerous nonfiction books, including biographies of the main actors, the Starkweather Rampage has inspired several acclaimed motion pictures, including Badlands (1973), Kalifornia (1993), Natural Born Killers (1994), and Starkweather (2004), the made-for-TV movie Murder in the Heartland (1993), the Bruce Springsteen ballad “Nebraska,” and a work of visual art, Redheaded Peckerwood (2011), by photographer Christian Patterson, which features a collection of photos taken along the 500-mile route of the murder spree.

Thus one must commend the two authors of The Twelfth Victim for their willingness to wade into this crowded alcove of American pop culture.[1] That the authors, Linda M. Battisti and John S. Berry, Sr., are both attorneys—the former a prosecutor, the latter a criminal defense attorney—is good news and bad news for the reader.

The good news is that The Twelfth Victim is a work of diligent investigation. If you are curious about the facts of the murder spree and the subsequent two trials, this book will satisfy that curiosity. The authors have poured over the investigative reports, the pre-trial documents, and the trial transcripts and exhibits—and they present those materials in a coherent and compelling fashion.

As the authors demonstrate, Caril Fugate was a victim of the miscarriage of justice at the center of this book. She was the youngest person ever to be put on trial for first-degree murder. Only 14 years old and in 8th grade when she was taken captive by Starkweather, she was, as the authors emphasize, “emotionally and psychologically immature. She had no prior arrests. And at Starkeweather’s hands she witnessed a series of hideous murders that, naturally, traumatized her.”

From her grueling 12-hour back-to-back interrogations to her pre-trial isolated incarceration in a mental asylum to the failure to advise her of her right to an attorney to the prosecution’s brazen coaching and subtle enticing of Charlie Starkweather to provide incriminating testimony against Caril that was inconsistent with his prior versions of those facts, the authors provide the reader with some of the most powerful and heart-breaking justifications for the United States Supreme Court’s subsequent decision in Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U.S. 436 (1966), which held that statements by a suspect in police custody made in response to an interrogation are inadmissible at trial unless the prosecution can show that the defendant (a) was informed of the right to consult with an attorney both before and during questioning, (b) was also informed of the right against self-incrimination prior to questioning by police, and (c) not only understood those rights, but voluntarily waived them.

But the good news about this book is also the bad news: the authors are trial lawyers, and thus their focus is on the conduct in and around the courtroom back in 1958. The guilty verdict in Caril Fugate’s trial and her sentence to life in prison arrive at page 208 of the 215-page narrative. The story of Caril Fugate’s life from the moment she stepped into prison in 1958 until she walked out 18 years later receives just three paragraphs, and her life after prison takes up less than a page, ending with an automobile accident in which her husband was killed and she was critically injured. The final sentence of the book: “She spent months recovering.”

More than a half century has passed since that eighth-grade girl entered prison, and nearly four decades have passed since that 32-year-old woman walked out of prison. All the authors tell us she was a model prisoner who taught Bible classes and worked as a geriatric aide, and that when she was granted parole she worked as a hospital orderly and a nanny and eventually married.

As readers, we close the book frustrated by a sense of incompleteness, by a story that feels cut off in the middle. We want to know more about Caril Fugate’s life after that Trial of the Century, what it was like to come of age in prison, to re-enter society as an ex-con convicted of being an active accomplice to one of the most notorious murderers of the century.

Perhaps our frustration is the result of a culture that has embraced the redemption story dating as far back as Moses wandering in the wilderness and as recent as, to name just two of dozens of examples, Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory and the motion picture aptly named The Shawshank Redemption. We yearn for the rest of the story, for the part that comes after the fall from grace. Perhaps the answer is that the Whiskey Priest in The Power and the Glory and the Tim Robbins and Morgan Freeman characters in The Shawshank Redemption are fictional, while Caril Fugate is real. And maybe that’s the best, and perhaps that’s the only, answer. Nevertheless, the post-conviction story of Caril Fugate over the past 50-plus years deserves, if not its own book, more than just a few pages of this one.