Sheriff David Clarke Jr. may put some people in mind of African American high school principal Joe Clark (“Crazy” Joe Clark to his legion of detractors): an authoritative, outspoken black man with some measure of bureaucratic power who winds up being championed by white conservatives. Joe Clark won fame back in the 1980s when he became the principal of the dysfunctional, indeed dangerous, Eastside High School in Paterson, New Jersey. He got this job because of the miracle he performed in transforming School No. 6, a terrible elementary school in a terrible Paterson neighborhood. Frank Napier, school superintendent, convinced a reluctant Clark to go to Eastside. In his lonely fight against violent drug-peddling thugs, apathetic, hostile students, uninspired and incompetent teachers, and indifferent, unsupportive parents, Clark, armed with a baseball bat and a bullhorn, marched the halls of the school, berating teachers—yelling at parents, and organizing “works” projects for the students—wrenching order and discipline and ultimately some level of success out of chaos and horror. He instilled pride in the students and a sense of hope and mission in the teachers. Something like that happened.

Morgan Freeman starred in the 1989 film—Lean on Me—about Clark’s battle against the incompetent liberal power structure that indulged or ignored black children, displaying no real concern for their education. (That liberties were taken in the filming nearly goes without saying.) The conservative publisher Regnery issued Clark’s 1989 book about his time running Eastside High, Laying Down the Law: Joe Clark’s Strategy for Saving Our Schools. (It is hard to imagine in our intensely polarized political climate today that Freeman would ever play someone like Clark, a Republican, and even harder that Hollywood would make a film about him.) Clark did bring order to Eastside, but the school showed no improvement academically. His critics complained that he expelled a few hundred of the worst or the most hopeless students which made his job easier. The title of his book says it all: a new sheriff had come to town and black people, a disorderly, undisciplined, and semi-pathological bunch, needed to have someone come in and “lay down the law.” For those who liked Clark, it all feels a bit like the morality of a western. For many of Clark’s detractors, it seemed awfully much like the belief of plantation owners and overseers: Negroes needs a stern, even harsh, regimen in order to be useful to themselves and others. David Clarke is of course literally a sheriff, a law and order guy of the first magnitude. His book does indeed “lay down the law.” He, like principal Clark, is also that somewhat rare bird: a black Republican. That is a bit like being a blonde in a brunette town, to use an old expression. What is even rarer is that he is a black Republican who, because of circumstances, has been forced to run for sheriff as a Democrat. That is a bit like being a blonde with an ill-fitting, ratty-looking brunette wig in a brunette town. Clarke, being outspoken as a conservative is his stock-in-trade, does not even pretend to wear the bad-looking wig, but rather enjoys stomping all over it. If Hollywood ever makes a movie about David Clarke, I would be surprised.

Sheriff David Clarke Jr. of the Milwaukee County Police Department (elected four consecutive terms since 2002) also reminds us of other self-promoting cops of the past like former Philadelphia mayor Frank Rizzo, former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, former Prohibition agent and Cleveland director of public safety Eliot Ness, and former Arizona sheriff and immigration hardliner Joe Arpaio. The main difference is that Clarke is African American. In this age of mass incarceration and black over-representation in prison, the fact that a black man can become so renowned for tough-sounding law and order rhetoric is something of a minor feat, an ironical bit of PR, even though Clarke is hardly unique as a big city, big-time black cop. Perhaps he aspires to higher political office. At 60, he ought not to wait much longer to hunt bigger game.

Sheriff David Clarke Jr. of the Milwaukee County Police Department, like Paterson, New Jersey’s Eastside High School principal Joe Clark, is that somewhat rare bird: a black Republican. That is a bit like being a blonde in a brunette town, to use an old expression. What is even rarer is that Clarke is a black Republican who, because of circumstances, has been forced to run for sheriff as a Democrat. That is a bit like being a blonde with an ill-fitting, ratty-looking brunette wig in a brunette town. Being outspoken as a conservative is his stock-in-trade, Clarke does not even pretend to wear the bad-looking wig, but rather enjoys stomping all over it.

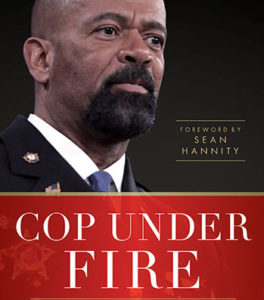

Cop Under Fire is a rambling monologue, aggressively expressed if not always cogently persuasive as a set of arguments. It would serve Clarke adequately as a campaign book as it expounds his policy views in a number of areas, some only tangentially related, at best, to law enforcement. The book is not without a kind of design or, should I say, strategy. The book begins autobiographically with Clarke recounting a boyhood incident when he at the age of 13 raises a clenched fist to police officers who drive by his house back in 1969. His father, a Korean War combat veteran, for whom Clarke is named, takes matters in hand, telling his son to “never mess with the police.” The opening of the book gives the reader a picture of a boy who was reared in a loving and traditional family—a strong, masculine father who strictly but caringly disciplined his children, an at-home mother, a Catholic school education that instilled respect for authority, a set of accomplished uncles. Clarke’s family lived in a housing project for a time but got out, the message public housing was supposed to convey but that many blacks did not heed or understand who wound up trapped there. The book’s beginning belies the myth of the dysfunctional black family while, at the same time, underscoring it: after all, what Clarke describes happened in the past, his family is something of a relic. The present, distorted by failed anti-poverty programs and a guilt-ridden white liberalism and leftist radicalism that did not liberate the black community as much as unravel the stressed strings that held it together, is another matter altogether. What makes Clarke a conservative is his desire (some would say his fantasy) of returning to a time of black self-discipline and traditional social structures. The irony of the conservative view is that the black community and the black family were somehow stronger and more self-reliant when it was afflicted by more severe and savage racism (many blacks believe this too) than it is now, although by virtually every metric blacks are enjoying more success today—such as it is—in this country than they ever have in their history. The other irony of the conservative view is that blacks, especially middle-class blacks, have been coddled and indulged with affirmative action, multiculturalism, and schemes of diversity, and have more opportunities and fewer excuses for failure than ever, yet this very liberalism that has availed them these opportunities and advantages has perversely wrecked them as a family and a community. I suppose it is one of the grand complexities of the human condition that this extraordinary contradiction could be true, but it is unlikely. What is more clear is that conservatives themselves are afflicted with the contradiction that they cannot abide blacks being failures but they also cannot abide blacks being successful in ways that demand reparations from whites. This position puts a black conservative in an interesting bind of demanding a purity of motive and a purity of effort, unsullied by resentment or ferocious opportunism, on the part of blacks that would seem to say that their uplift, their redemption, their salvation, must be exceptional but also common. This is the politics of racial virtue whose appeal for the conservative is that it is so old fashioned, so Booker T. Washington-esque, so undemanding of patronage, so merit-centric, so, shall we say, mythically American. It is asking a lot! And it keeps blacks imprisoned in a particular view of the civil rights movement as a quest for becoming American, so blacks always remain civic apprentices-in-training. (The left has its own form of the politics of racial virtue that keeps blacks imprisoned in a particular view of the civil rights movement as a quest for transforming America, so blacks always remain avenging angels. That is a story for another day.)

Cop Under Fire has a chapter on black conservatives where Clarke argues, with partial insight, about the difference between white and black conservatives:

“Most people assume being a black American conservative is like being any other conservative. After all, we believe in limited government and low taxes through a restrained federal bureaucracy; we believe the Constitution protects individuals, not groups; we believe a strong national defense and safe streets are critical to liberty, freedom, and an orderly society; we believe in states’ rights; and we frequently believe in a Higher Power.

That, however, is where the similarities end.

To be a black conservative in America is to be orphaned personally and politically by the Left. That’s because the Left wants us to be set apart … We are—they would have you believe—abnormal. …

Being black and conservative is such an odd combination that we need a new classification. Don’t believe me? Take a look around the world of politics. Sarah Palin is not a “female conservative.” She just “conservative.” Rush Limbaugh is not a “white male conservative.” He’s just “conservative.” But Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas, Dr. Ben Carson, economist Thomas Sowell, four-star general Colin Powell, and former US Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice belong to a rare class. They belong to a special category of people so unique that their oddity can’t be contained in one word. These people are never described simply as “conservatives.” They are “black conservatives”—no matter what else they accomplish with their lives. By adding the descriptor “black,” the Left wants you to begin to think of the phrase of “black conservatives” as an oxymoron … words that are apparently contradictory appearing together: “jumbo shrimp,” “pretty ugly,” “living dead.”

This begs the question: why should Clarke or any other self-identified black conservative care what the Left thinks or how the Left wishes to define them? In good measure, the answer to this is Clarke’s statement a bit later in his chapter on black conservatives, “… ‘blackness’ is a status the Left awards and revokes.” [Clarke’s emphasis] That the Left defines blackness is undeniably true and gives the white Left particularly a kind of hegemony or at least a certain amount of say-so about black identity that the black conservative would argue that it does not deserve but it very much desires as whites, no matter their political stripe, have always desired. But in another bizarre way, black conservatives seek a kind of approval for the legitimacy or authenticity of their blackness from the very people they despise and criticize as being an illegitimate, even iniquitous, political force, namely, the Left.

What makes Clarke a conservative is his desire (some would say his fantasy) of returning to a time of black self-discipline and traditional social structures. The irony of the conservative view is that the black community and the black family were somehow stronger and more self-reliant when it was afflicted by more severe and savage racism (many blacks believe this too) than it is now, although by virtually every metric blacks are enjoying more success today in this country than they ever have in their history.

Clarke, not surprisingly as he is a hardcore cop, blasts Black Lives Matter, giving his own take on the Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin, and Tamir Rice cases, which, it nearly goes without saying, is far more sympathetic to the police versions of events. (He calls the organization/movement Black Lies Matter. To be sure, these views have led to more than a few run-ins with liberal blacks and mainstream black opinion.) He is skeptical about both the claim of mass incarceration and its effects. He in fact supports mass incarceration: “Communities in which most crimes occur don’t have support structures in place for social alternatives to incarceration. Consequently, it’s not wise to put [perps] back into the community to claim more black victims.” It is the contention of the black conservative that he or she is protecting the black community by identifying the true victims, those who have been harmed or affected by criminals, not through some strange, largely bourgeois-obsessed inversion making the criminals the victims and the victims altogether invisible or irrelevant. (A conservative acquaintance calls this the “McHeath syndrome,” after the attractive criminal character in John Gay’s 1728 play, The Beggar’s Opera.) As Clarke writes, “If you go to a neighborhood riddled with crime, the people who live there don’t want drug dealers and users to be put back on their streets. Who would? Residents of these neighborhoods want tougher sentencing, not more lenient sentencing. Only in the twisted logic of liberal class and race guilt would putting druggies back on the street seem like a good idea.” This is tantamount to arguing that what those who are victims of crime desire is the best solution to their problem. One can argue that this is equivalent to the grunt’s view of the war. It is clear that this is not always the case that the grunt’s view is accurate, although there is something compelling to be said about the implication in Clarke’s observation that only the privileged want criminals on the street because they are least affected by the result of their altruism.

Clarke insists that prison should be a tough punishment, not a pleasant experience. His example of taking over the Milwaukee House of Corrections and making the prisoners follow a schedule and giving troublesome prisoners a foul-tasting but nutritional sound concoction called Nutraloaf does not seem especially extreme; certainly, it was not, by his account, anywhere close to a return to the brutalities of some place like Angola prison and its system of convict labor. Yet by his account he was politically attacked for this, for creating a “boot camp” experience. (I once had a conversation with the Muslim chaplain for Petosi Correctional Center, an African American, who felt the same way: sentences should be shorter, he explained, but prison should be a very harsh experience so that no one would wish to return. Whether this makes the recidivist reform or simply makes him more ruthlessly determined than ever not to be caught is an open question.)

Clarke’s argument against the TSA and the mass searching and screening of airline passengers will find many sympathetic readers; his argument in support of religious beliefs that confound or oppose civil law will find far fewer nods at least from the liberal set. But of course he is not writing for the liberal set. It is hard to imagine Regnery books being read by many liberals or left-leaning people.

Clarke gave the closing address at the recently ended Conservative Political Action Conference where he said, in supporting President Trump’s immigration policy, “In President Trump we have chosen a leader—a leader who I expect many of you in this room well know I both campaigned and vigorously supported for the highest office in this land.” In the fog of this particular current war sweeping our land, it is hard to know whether these were “brave words for a startling occasion” or startling words for an unreal occasion. Such is the mystery of the black conservative.