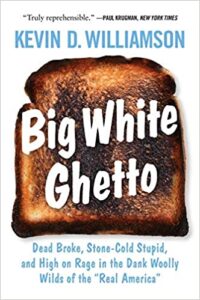

Big White Ghetto: Dead Broke, Stone-Cold Stupid, and High on Rage in the dank Woolly Wilds of the “Real America”

“Capitalism, in the long run, will win in the United States, if only for the reason that every American hopes to be a capitalist before he dies.”

—H.L. Mencken, “On Being an American” ¹

1. Wrap Your Troubles in Dreams

This book is a collection of pieces Kevin D. Williamson wrote for National Review as that magazine’s roving reporter. Each dispatch, as they might accurately be called, tells a vignette about a different place, typically dysfunctional, in the United States. Taken together, they might be read thematically as a view of the underbelly of White America, an underbelly that sometimes seems like a shark’s, sometimes a whale’s, but most often a sort of preternaturally alabaster slug, bloated on the garbage and bilge water of American life. The essays, lively and quirky, give credence to the old R&B group War’s anthem of the early 1970s: “Don’t you know/that’s it’s true/that for me/and for you/the world is a ghetto.”

National Review, to refresh our readers’ memory, was the cornerstone journal of the American Conservative Movement, founded by William F. Buckley in 1955, a few years after having made a name for himself with his treatise against the unacknowledged and hypocritical liberal bias of his undergraduate alma mater, Yale University, entitled God and Man at Yale (1951), the book that told us that prestige college education was a bunch of leftist, collectivist claptrap and flapdoodle long before Judith Butler and Critical Race Theory enflamed the rage of the right.

It is far from certain whether National Review, the Gray Lady of conservative commentary and reportage, remains the cornerstone of something called the American Conservative Movement. It has so many online competitors these days like Breitbart, Hot Air, The Bongino Report, Liberty Daily, The Federalist, Townhall, American Thinker, Red State, Rantingly, PJ Media, Whatfinger, and the list goes on. Obviously, there is an audience out there for anyone who is rightwing these days and wants the world to know it; so, with any luck, you too can become Sean Hannity or Ann Coulter or Laura Ingraham in the ever-expanding universe of conservative commentary media. Another problem for National Review is the stick of dynamite that Donald J. Trump has thrown into the edifice of American conservatism. It can be argued that Trump has fractured it, undone it, revealed it, exposed it, enlivened it, popularized it, bent it like Beckham, but the White populism that now drives it as a kind of insurgency has clearly made National Review less influential than it was, say, back in the Reagan era. National Review intellectuals helped to elect Reagan; they desperately wanted to defeat Trump. A lot happened in forty years to the conservative movement and the Republican Party but we need not rehearse that here.

Each dispatch, as they might accurately be called, tells a vignette about a different place, typically dysfunctional, in the United States. Taken together, they might be read thematically as a view of the underbelly of White America, an underbelly that sometimes seems like a shark’s, sometimes a whale’s, but most often a sort of preternaturally alabaster slug, bloated on the garbage and bilge water of American life.

Buckley of course defined the twin principles of conservatism: hatred and destruction of communism and the elimination of the welfare state. Love capitalism, love tradition, and love individual freedom, was the motto. (For Buckley, it was also Love Catholicism, although Brent Bozell Jr., one of the initial contributors to National Review and Buckley’s running buddy, did not think NR nearly Catholic enough and left the fold to start his own journal.) Post-WWII conservatism was, you might say, the fight to retain the original Constitution and to oppose fiercely the new one being born in the era of the civil rights movement and the selective court challenges of the NAACP. Part of Buckley’s fight was to make conservatism respectable and not some sort of crank ideology of political quackery and reaction, your crazy-uncle-at-the-Thanksgiving-dinner-table’s philosophy: musty, anti-intellectual, and not worthy of being taken seriously. (So now we know that it was not simply Black people with their racial uplift philosophy who were concerned with the politics of respectability, who wanted to, as they say, swim in the mainstream.) In this regard, Buckley read out of the conservative movement the John Birchers and their conspiracy theories, the anti-Semites and neo-Nazis, objectivist Ayn Rand (who incisively critiqued the movement after she was banished), the George Wallace-types (although Buckley supported racial segregation longer than he should have as constitutionally protected freedom of association). If one could imagine Albert Jay Nock and G. K. Chesterton giving birth to an American publication, the result would have been something like National Review, where a bunch of ex-commies like Whittaker Chambers and James Burnham swore that they had now seen the light; where conservatism endorsed American exceptionalism, the triumphant version of American history, the noble experiment of American republicanism, America as the social and political magnet, the beacon, of the European immigrant; in short, something called in high school civics and English classes, the American Dream.

“[The American] is led no longer by Davy Crocketts; he is led by cheer leaders, press agents, word-mongers, uplifters.”

—H. L. Mencken, “On Being an American”²

2. And Dream Your Troubles Away

This “respectable” conservatism eventually ran into the buzzsaw of Trump who steamrolled it as a lot of establishment, rich White boy nonsense, prissy, rhetorical, removed, elitist, and too interested in not being rude and, in fact, overly concerned with being acceptable to the very people it was supposed to overthrow or opposed. National Review, to a person, denounced Trump and became one of the leading lights of the anti-Trump campaign, fighting him for the soul of American conservatism or for their previous level of influence, which for NR might amount to the same thing. Conservatism, in the NR corner of the world, still wants to be respectable and Trump is not that but Trump not being respectable is among the least of his problems. In many ways, it is not a problem for Trump at all but rather an aspect of his charisma, such as it is.

Williamson bashes Trump in these pages with a considerable verve but the strongest essay here, “The White Minstrel Show” connects the dots between the appeal of Trump and poor Whites “acting white,” as Williamson puts it. “White people acting white have embraced the ethic of the white underclass, which is distinct from the white working class, which has the distinguishing feature of regular gainful employment. The manners of the white underclass are Trump’s—vulgar, aggressive, boastful, selfish, promiscuous, consumerist.” (198, emphasis Williamson) He begins the essay writing about Black actors and entertainers who have made their names and fortunes “acting Black.” (Robert Townsend made an amusing movie about this in 1987 called Hollywood Shuffle.) Whether this has been a good or bad occurrence for Blacks, he leaves an open question. (It is certainly not new.)

But Whites “acting white,” is not new either. Whites have always acted White, embodied Whiteness in a variety of ways including an attitude and set of assumptions about one’s place in the world that most non-White people found, at one time or another, irritating or oppressive. But Williamson sees the rise of Trump as a form of utter White declension, the abdication of taste, standards, achievement, manners, the city as a place of culture and institutions, coupled with an unfounded claim that somehow the forgotten Whites represent the real America. As Williamson writes, “No, the ‘real America,’ in this telling, is little more than a series of dead factory towns, dying farms, pill mills—and, above all, victims.” (201, emphasis Williamson)

Williamson bashes Trump in these pages with a considerable verve but the strongest essay here, “The White Minstrel Show” connects the dots between the appeal of Trump and poor Whites “acting white,” as Williamson puts it.

Here is a “real” America that is empty and fake that finds a hero who is also fake. Trump is no White guy straight outta Appalachia: “He has had a middling career in real estate and a poor one as a hotelier and casino operator but convinced people he is a titan of industry. He never managed a large, complex corporate enterprise, but he did play an executive on a reality show.” (141) He got his start from his rich father. He went to prestigious schools. He is everything “real” America is supposed to despise. Yet he is their hero. There is nothing new in the analysis of Trump here, although these observations were fresher when they originally appeared at the time Trump was running for president or had just been elected. In one respect it is right to call Trump a racist (and not because of his remarks about the Charlottesville incident which were edited) but because his appeal to his White base is the same as the appeal of George Wallace, Ross Barnett, James Eastland, Strom Thurmond, and the other segregationist politicians of the Cold War era: they represented the idea that Whites were losing something that they were not supposed to lose, that Whites had a complaint about being neglected or treated unfairly because they were White, that Whites were owed something. It is amazing that dysfunctional, incompetent, mediocre Whites had the audacity to come up with their own form of special pleading based, in part, on complaining that that was all Black people did and it was the reason they got all the concessions that they did not deserve.

It was this that Williamson was getting in “The White Minstrel Show.” Williamson, who grew up among White underclass and working-class types in an East Texas dysfunctional family, makes the argument in his book that poverty is caused by bad decisions, not “scheming elites, immigrants, black welfare malingerers, superabundantly fecund Mexicans, capitalism with Chinese characteristics, Walmart, Wall Street, their neighbors . . .” (206) His proof of this is that poor Whites supported Trump! I found that alone clinched his point and was funny to boot.

(I thought bad decisions were why a lot of Black people were living lives that were harder than they needed to be. I grew up poor and had a friend who when he became a teenager decided to become a gangbanger. I thought he was nuts. I even told him at one point, “How can you give up school for the streets?! School is easy. The streets are hard.” The kid was a lot smarter than I was. He could have faked an interest in academics and the White elite would have given him every kind of scholarship they could think of. He did not listen to me and was dead before he was twenty-five years old. Bad decision! People always think that in comparing the two of us, I was the hard worker because I stayed in school, completed my education, had a career, and so forth. I am certain he worked far harder in his short life than I ever did. As the old saying goes, in school, first you get the lesson and then you get the test. On the streets, first you get the test, and then you get the lesson. That is making learning much harder than it needs to be.)

Williamson’s book is a journey through “real” America, small towns with no futures, big cities gone to seed:

• Corrupt city governments burdened with huge public employee pension obligations like San Bernardino (defund the police is a movement that is about 30 years too late and too unserious; where was it when police and firefighter pensions were going through the roof).

• The gambling joints of poor America (I took the bus ride from Philadelphia to Atlantic City that Williamson describes many times with my mother as, in her old age, she became hooked on gambling and I remember the unpleasantness of those trips vividly), where the suckers are the bottom feeders on slot machines keeping cheap, garish casinos flush in the last refuge where the persecuted working-class smoker can still smoke indoors, indeed, can chase the virtuous bourgeoise nonsmoker from the place by simply exhaling.

• States permitting the sale of legalized marijuana in the hope that the revenue will help the general fund without the least clue of how all of this contributes to the massive problem of White drug addiction in the United States; as Williamson notes, when White shoot up heroin in today, it is medicalized but when Blacks did it in the 1940s and 1950s, it was criminalized.

• The depressing streets of Portland where ignorant, bratty, privileged White kids try to find meaning in their lives by playing revolutionary. (I want my Selma! I want my Birmingham! I want my Watts! I want my Finland Station!); the thought of these people running something is even more chilling than the failures we are already stuck with.

• The porn festivals with men who can only deal with sex as a fantasy with women with augmented breasts that look like bowling balls (“o, my aching back,” they must say every night), a dreary hustle where everyone is somebody’s mark.

• The small towns in Appalachia and Texas where Whites are waiting for their welfare checks, “the draw,” as they call it, whose first excuse for anything is “My check didn’t come.”

What Williamson describes is Loser America. H. L. Mencken, with more satirical zeal, blasts the notion of American exceptionalism in his famous essay, “On Being an American”: “Third-rate men, of course, exist in all countries, but it is only here that they are in full control of the state, and with it of all the national standards. The land was peopled, not by hardy adventurers of legend, but simply by incompetents who could not get on at home, and the lavishness of nature that they found here, the vast ease with which they could get livings, confirmed and augmented their native incompetence.” Thomas Sowell, in his book Black Rednecks and White Liberals (2005), argues that Black Americans were adversely affected by slavery not simply by the barbarous nature inherent in the institution but by the barbarous nature of the particular Whites who enslaved them: “The cultural values and social patterns prevalent among Southern whites included an aversion to work, proneness to violence, neglect of education, sexual promiscuity, improvidence, drunkenness, lack of entrepreneurship, reckless searches for excitement, lively music and dance, and a style of religious oratory marked by strident rhetoric, unbridled emotions, and flamboyant imagery.”³ Sound familiar? Are not those all the characteristics that are generally associated with Blacks? Sowell continues, “Much of the cultural pattern of Southern rednecks became the cultural heritage of Southern blacks, more so than survivals of African cultures with which they had not been in contact for centuries.”⁴ Now, there is a critical race theory for you! Bad enough to have been enslaved. Worse to have been enslaved by the most useless and “third-rate” type of Whites who pulverized you with their own degradation. Loser America, where is thy Dream?

I am not so sure if Williamson is a conservative as much as he is a contrarian, at times a kind of White Stanley Crouch, though less verbose. At times, a kind of Hunter Thompson but less gonzo. I did not always agree with his interpretation of the world as he saw it, but I always found what he saw stimulating and more than occasionally trenchant.

What Williamson describes is Loser America. H. L. Mencken, with more satirical zeal, blasts the notion of American exceptionalism in his famous essay, “On Being an American.”

In 2018, Williamson briefly worked for The Atlantic. He was fired after other writers at The Atlantic complained about comments he made a few years earlier about capital punishment as perhaps suitable for the “crime”⁵ of abortion. The question posed was, if abortion is murder, who do you punish someone for it? (He is, like the entire NR crowd, against legalized abortion.) Perhaps he should not have been fired for that. After all, he was hired to provide some diversity of opinion for The Atlantic. And he is a far more interesting writer than many conservatives (and liberals) who work at the writer’s trade are. But then again what are the chances that National Review would hire a quirky, unpredictable liberal writer who serves on the board of Planned Parenthood? There are limits to diversity, equity, and inclusion, don’t cha know! Those that like diversity like the sort of diversity they like.