How Trump Is Making Black America Great Again: The Untold Story of Black Advancement in the Era of Trump & Coming Home: How Black Americans Will Re-Elect Trump

Joseph … not only uses his inner resources and the means at hand to take advantage of the most unlikely opportunities to succeed in the circumstances in which he finds himself; he also makes himself indispensable to the welfare of the nation as a whole. Those who follow Moses are forever talking about going back home; but to Joseph, to whom being at home was as much a matter of the spirit as of real estate, anywhere he is can become the Land of Great Promise.

—Albert Murray, The Hero and the Blues ¹

1. Ideas Have Consequences

In the fall of 2016, I taught a class entitled “A Cultural History of American Conservatism, from Hoover to George Will.” As I went over the syllabus on the first day of class, I informed the students that two weeks of the semester would be devoted to examining the works of some of the leading Black conservatives such as Clarence Thomas, Shelby Steele, and Thomas Sowell. One student looked stunned: “I didn’t know there was any such thing as a Black conservative,” he said incredulously.

Certainly, Robert C. Smith, author of Conservatism and Racism, and Why in America They Are the Same (SUNY Press, 2010), would agree that there can be no such thing as a Black conservative. He writes that “most persons usually thought of as black conservatives—Booker T. Washington or George Schuyler—were really accommodationists, cowards, or opportunists.” Blacks cannot be conservative because, according to Smith’s reasoning, 1) they have nothing to conserve and 2) (which follows from the first point) they have always opposed the status quo in the country; indeed, they were never a part of the status quo, the White status quo or the White norm, in the country at any time in its history. They were always the exceptions to or aberrations from it. Whites have considered Blacks to be, well, for lack of a better term, a mistake of one sort or another, and a problem. The idea of the American status quo was always commensurate with the idea that Blacks must occupy a social and political space that acknowledges and reinforces the idea that they are a mistake and a problem, arising from the fact, unfortunately, that they are not White. This interpretation of why there are no Black conservatives may be true. The argument is compelling. But self-identified Black conservatives do not consider themselves “accommodationists, cowards, or opportunists,” certainly not opportunists in any pejorative or mercenary sense or in any way that would distinguish their actions from the opportunism of Blacks who are leftists or liberal. In politics, we all are hitching an ideological ride that is providing gratification of some sort, material, or emotional. The overall judgment here about Black conservatives, hardly charitable, is made by someone who is not one of them and does not like them.

If Moses for Blacks is the wrathful myth of the Implacable Rebel as Redeemer who leads his people from bondage to freedom, then Joseph is the burrowing-from-within myth of the Provider, the Schemer, the Conservator who enables his people to survive in the land of bondage.

George Schuyler, the Harlem Renaissance journalist and satirist (his 1931 novel, Black No More, about Black people finding a formula that makes them White, is hilarious with some bitter truths about self-hatred among Blacks), became, by the 1960s, a writer for the right-wing John Birch Society, opposed the 1964 Civil Rights Act, condemned Martin Luther King Jr. as a communist-inspired agitator, and voted for 1964 Republican presidential nominee Barry Goldwater, which very few Blacks did as they considered Goldwater a racist right-winger. In this regard he was little different from the White conservatives of the day like William F. Buckley, Brent Bozell, William Rusher, or Russell Kirk: Schuyler hated the welfare state, communism, collectivism, and liberal social reformism, which, according to the conservative is imposed on the defenseless public by the White privileged intelligentsia. (See William Graham Sumner’s influential 1883 essay, “The Forgotten Man,” which denounced the imposition of social reform, in part, as an abuse of bourgeois privilege.) Schuyler loved capitalism, individual freedom, the ideas of personal responsibility and self-reliance. So did the man called by his admirers “The Wizard,” the legendary Booker T. Washington, the father of Black conservatism, if there is such a thing. (On this last point of self-reliance, Schuyler stated “After all, the welfare of Negroes is primarily the responsibility of Negroes.”²) But there is more to consider about the conservative Black. In his 1966 autobiography, Black and Conservative, Schuyler writes:

“The American Negro is a prime example of the survival of the fittest, and it is enlightening to contrast his position today with that of the Amerindian. He has been the outstanding example of American conservatism: adjustable, resourceful, adaptable, patient, restrained, and not given to gambling what advantages he has in quixotic adventures. … Had he taken the advice of the minority of firebrands in his midst, he would have risked extermination.

“I learned very early in life that I was colored but from the beginning this fact of life did not distress, restrain, or overburden me. One takes things as they are, lives with them, and tries to turn them to one’s advantage or seeks another locale where the opportunities are more favorable. This was the conservative viewpoint of my parents and family. It has been mine through life, not consistently, but most of the time.” ³

Schuyler suggests, first, that Black conservatism is, in part, the stoicism of the blues; that is, accepting misfortune without rancor or bitterness as with the matter-of-factness of the blues singer. Second, it is, in part, the fatalism of a moral providence, or that nothing that happens in life is meaningless. Third, Black conservatism is the cunning of the underground or the law that only the strong survive, especially among the powerless. In other words, instead of the rebellion of Moses, Schuyler offers the sly adaptations of Joseph. If Moses for Blacks is the wrathful myth of the Implacable Rebel as Redeemer who leads his people from bondage to freedom, then Joseph is the burrowing-from-within myth of the Provider, the Schemer, the Conservator who enables his people to survive in the land of bondage. Instead of calling Booker T. Washington an Uncle Tom, it is more fitting to see him as the Provider, the Custodial Conservative, the Institution Builder, or, as Ralph Ellison called him in Invisible Man, the Founder. Black writer Albert Murray called Joseph “the epic hero of the blues tradition … [who] goes beyond his failures in the very blues singing process of acknowledging them and admitting to himself how bad conditions are. Thus his heroic optimism is based on aspiration informed by the facts of life.”⁴ I suppose we can think of Black conservatives as quislings but what if they are offering the prototype of Joseph. Of course, we all know that human life has always been an unending map of misreading.

2. I Saw the Light

Jesus, wash away my troubles

While I’m traveling here below

For I’ve got enemies

Lord, you know

—Sam Cooke and the Soul Stirrers, “Jesus, Wash Away My Troubles”

Well, I tell you what. If you have a problem figuring out whether you’re for me or Trump, then you ain’t Black.

—Democratic Presidential Nominee Joe Biden, May 2020

What we now call Black conservatism, which revolves around Black people’s re-identification or re-engagement with the Republican Party, arose as a particular and pronounced presence during the Reagan years, which is when such key figures associated with this movement as economists Thomas Sowell and Walter E. Williams, jurist Clarence Thomas, and conservative academic Shelby Steele emerged. Black conservatism was largely meant to counter the liberalism of the Civil Rights Movement, the prevailing liberal interpretation of Black history, and to challenge the liberal assumptions of social policy directly affecting Blacks. The Black conservatives’ major argument was that these liberal social policies, born during the age of affluence and optimism of the Johnson administration, had failed. What galled this faction was not simply the failure of the policies but that liberals would not acknowledge their failure, that liberals would not acknowledge their mistakes, and made criticizing them a matter of race loyalty and race authenticity. What further galled the Black conservatives was that they thought the case made by the Black liberals was, in large measure, just angry special pleading; Black people needed compensatory consideration, the benefit of the doubt, special boosts. The conservatives found this infantilizing (with Whites as permissive, overly concerned parents), dishonest, and degrading. Persecuted people can express their egos, their need for self-respect, in many ways.

What we now call Black conservatism, which revolves around Black people’s re-identification or re-engagement with the Republican Party, arose as a particular and pronounced presence during the Reagan years which is when such key figures associated with this movement as Thomas Sowell, Clarence Thomas, and Shelby Steele began to appear.

This form of Black conservatism, as contrasted to, say, the Nation of Islam or the Garvey UNIA movement or Afrocentrism, which were more militantly expressed forms of a more strident kind of Black conservatism, was never very popular, but its presence was felt. Most Black people, however they felt, knew it existed. Lines were formed and people had enemies: the liberals and leftists called the conservatives “Uncle Toms,” “Sellouts,” “Race Traitors,” and “Collaborators.” The conservatives called the liberals and the leftists “Race Hustlers,” “Race Whores,” and “Race Charlatans.” It is hardly surprising that the issue of who is being true to the race, who is speaking in the best interest of the race, should become such an intense issue among a group of people who have such an epic history of enduring horrendous persecution. Among such people, everything, including every insult, matters.

Black conservatives believe that Blacks:

1) must take personal responsibility for their situation and stop blaming others for it;

2) must stop voting in such overwhelming numbers for the Democratic Party, as the social democratic liberalism that that party espouses has not only not helped Blacks but has been absolutely detrimental to their situation, wrecking the Black family, laying waste to the Black community, and destroying Black education;

3) must stop permitting White leftist radicals from using them as a cudgel, a tool, to beat non-leftist Whites;

4) must stop supporting Affirmative Action which has only stigmatized and segregated Blacks in the competitive labor market and admission to prestigious schools by overvaluing their skin color, inflating their achievements, and undermining their faith in their skills;

5) must stop having babies out of wedlock and restore the presence of the Black father to the family;

6) must stop having abortions and permitting the slow genocide or enfeeblement of the race;

7) must oppose illegal immigration as it works against low-wage Blacks’ economic interest;

8) must stop the identification with, and the romanticizing and rationalizing of, Black criminality.

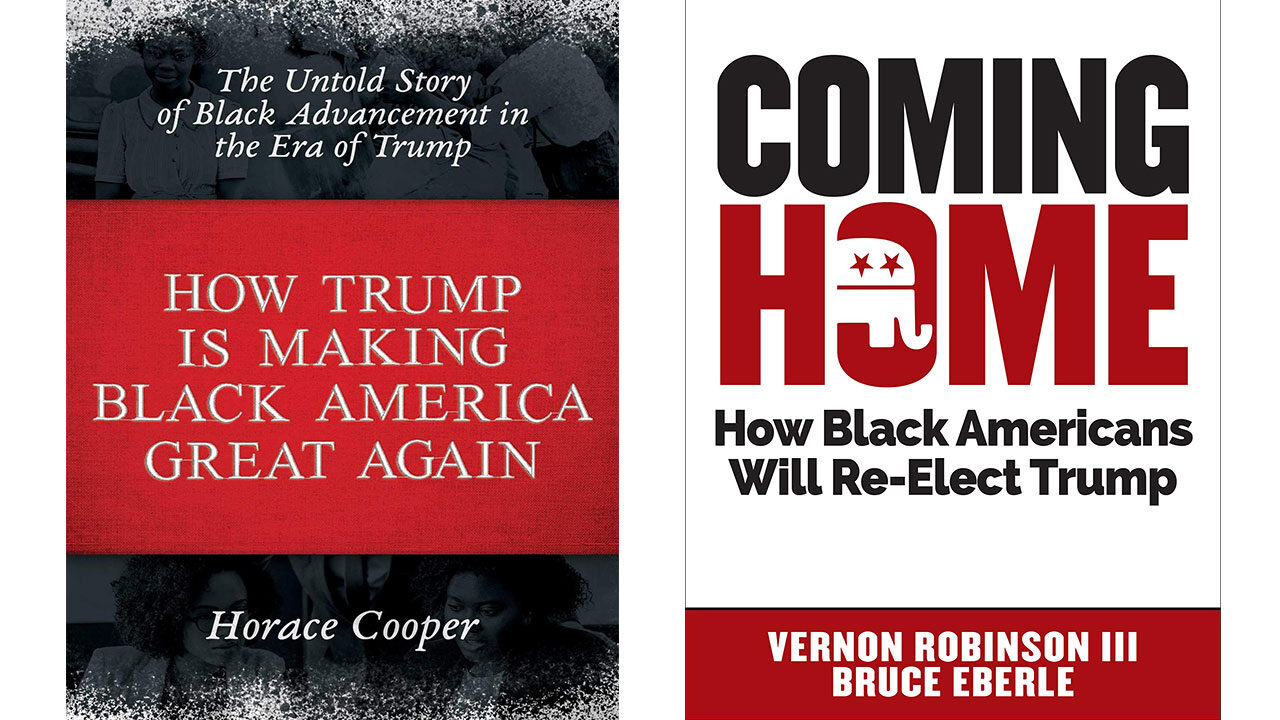

Both Coming Home: How Black Americans Will Re-Elect Trump and How Trump is Making Black America Great Again: The Untold Story of Black Advancement in the Era of Trump rehearse the points listed above. (Robinson, the co-author of Coming Home, and Cooper are prominent Black conservatives.) Coming Home is the weaker of the two books. It threads three basic themes:

First, Donald Trump was the first Republican presidential candidate in many years to make a pitch for the Black vote. He was rewarded with 20 percent of the Black vote in Pennsylvania and this made the difference in his winning that state and the election. Is it possible that Trump could win 20 percent of the Black vote nationally? If so, it would be impossible for the Democrats to win. It is not so counterintuitive that Trump might do that well against the Democrats this time because his policies have actually helped Blacks, Blacks are becoming increasingly disaffected with the Democratic Party, and Trump is more liked by Blacks than many people realize because he is an outsider and because Blacks made up a considerable segment of his audience when he starred in The Apprentice.

Second, Republicans received the overwhelming majority of the Black vote from the end of the Civil War to 1936 when Roosevelt ran for re-election. But even when Blacks switched parties during the era of the New Deal, Republican presidential candidates still received anywhere from 23 (Truman 1948) to 39 percent (Eisenhower 1956) of the Black vote. Nixon received 32 percent of the Black vote when he ran in 1960 despite not intervening to help Martin Luther King, Jr. avoid being sent to a chain gang for his non-violent protest in Georgia as John and Robert Kennedy did. It was only when Goldwater ran in 1964 and was labeled a racist for not supporting the 1964 Civil Rights Act that Black support dropped precipitously to 6 percent and has never risen higher than 15 percent since. Eberle (the White co-author) offers a mea culpa on behalf of all White conservatives (chapter 3) that Blacks rightly abandoned the GOP and saw conservatism as racism because conservatives did not join the Civil Rights movement and indeed, at times, actively opposed it. But Blacks can be recruited again to the Republican Party because they have supported the party in the past and because many are beginning to realize how detrimental Democratic liberal policies have been for them.

It is hardly surprising that the issue of who is being true to the race, who is speaking in the best interest of the race, should become such an intense issue among a group of people who have such an epic history of enduring horrendous persecution. Among such people, everything, including every insult, matters.

Third, the book gives a Manichean history of big party politics in America. The Republicans and the conservatives have been the true supporters of civil rights (the light) and the Democrats have been the racists, the party of slavery, segregation, the Ku Klux Klan, and now, identity politics and racial quotas (the darkness). (In fact, racial quotas happened under Nixon with the Philadelphia Plan, responding to pressure from Black leaders that voluntary Affirmative Action was not producing any change but let us not have such inconvenient facts ruin a good story!) We are told how crude and racist Lyndon Johnson was and how racially enlightened and supportive Goldwater was and yet a cruel reversal engineered by the Democratic Party and the mainstream press switched the identities of the two men. We are told seemingly every time Johnson used the word “nigger” in off-the-record remarks. (49, 52, 53) Including calling his Solicitor General and Supreme Court Justice appointee Thurgood Marshall “my nigger.” But the authors never refer to this quote about Johnson:

“In December [1966], Johnson had met at the White House with Democratic governors from the southern and border states during which they harangued the president for civil rights policy they believed was causing irreparable damage to the party, just as they resisted the desegregation that had been put into law. ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger,’ Johnson fumed to Joe Califano the following day, recalling the meeting. ‘That’s all they said to me all day. Hell, there’s one thing they better know. If I don’t achieve anything else while I’m president, I intend to wipe that word out of the English language and make it impossible for people to come here and shout ‘nigger, nigger, nigger’ to me and the American people.” ⁵

Nor is it ever mentioned when, for instance, in response to Johnson’s interest in racial quotas, Goldwater said, “All men are created equal at the instant of birth, Americans, Mexicans, Cubans, and Africans. But from then on, that’s the end of equality.” Or how Goldwater could use the words “free,” “freedom,” and “liberty” forty times in his 1964 acceptance speech and not once mention the Civil Rights Movement or Blacks.⁶ And Ronald Reagan is discussed in the book in such a way that the reader would never dream how he disparaged Africans when the United Nations voted to recognize communist China: “To see those, those monkeys from those African countries—damn them, they’re still uncomfortable wearing shoes.” Nixon, to whom Reagan made these remarks, thought they were funny. ⁷

Finally, there is the section by co-author Robinson telling how he became a conservative and a Trump supporter. He had started out politically as a liberal, but one day read Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose on the recommendation of a teacher and suddenly saw the light. (104) Most Black conservatives have these sorts of conversion-on-the-road-to-Damascus stories. Black conservatives also like to emphasize how heroically non-conformist they are because their views are so marginalized in the Black community. As Corey D. Fields notes in his sociological study of Black Republicans, “Put bluntly, black people are not providing a forum for African American Republicans.”⁸ But this isolation underscores their commitment: they have been brave enough to leave the Democrat “plantation,” a word Black conservatives love to use and both books under review here use often, and endure the shunning that goes with it. I suppose everyone thinks himself a hero of his own political life.

America’s two major parties have had a complex and difficult relationship with Blacks and for me to recount all the omissions and simplifications in this book is almost beside the point. Let it be said that the book abounds with them. Its purpose is as Republican propaganda for Black readers in hopes of getting them to vote for Trump. It makes some legitimate points but it will probably not be very effective in persuading Black readers, not because a plausible Black case for voting for Trump cannot be made. It is just that this book tries to convince readers by highlighting the least persuasive aspect of their argument: the racist history of the Democratic Party. In a class I taught in fall 2019 on the history of Black conservatism, not a single Black student cared much about the past history of either party, only what the parties were like now.

In a class I taught in fall 2019 on the history of Black conservatism, not a single Black student cared much about the past history of either party, only what the parties were like now.

Horace Cooper’s How Trump is Making Black America Great Again is a more strenuously argued book, with copious statistics demonstrating how Trump has improved life for African Americans across an array of categories. Here especially the tension in the argument is how much race consciousness the author displays versus how emphatic he is that Trump’s policy success with Blacks is because his policies are color-blind. This is not a contradiction, but it is what makes the Black conservative suspect in the eyes of other Blacks: How can remedies for Blacks, because of their unique subjugation, be colorblind and still work? Will they not be simply co-opted by the White majority? To this, the Black conservative responds that Blacks let their race over-determine their views and their fate while intensifying their sense of alienation, failing to understand that they are Americans too and benefit from policies that are good for Americans on the whole. As Cooper writes, “ … [this book] is an appeal to blacks, whites, and browns to understand the problems that gave rise to Donald Trump, why President Trump is addressing the ills that America is facing, and how Trump’s solutions benefit black Americans as well as the rest of America. Nor is this book an attempt to advocate that Trump, the individual, is ‘pro-black.’ Rather, it attempts to demonstrate how identity politics can be counterproductive to enacting broad-based economic, social, and foreign policies that benefit all Americans.” (12) The basis of the argument is more sensibly stated than in Coming Home.

Cooper asserts that “By almost every measure that counts, Black America lost ground under President Obama.” (11) This critique of Obama stresses the fallacy of identity politics: Blacks voted for a Black liberal candidate almost solely because of race. They did not vote for Trump, a White conservative, also largely because of race, and he has done so much for them. Discounting Obama is only a small part of the job here.

Cooper goes through the entire list of Black conservative debate points in his book.

• Trump’s anti-abortion stance and protection of religious objections to abortion have helped reduce the number of Black abortions—Black women get more abortions than any other female demographic—and help to revitalize the race both physically and morally. He points out that most Planned Parenthood clinics are located in or near poor neighborhoods and the eugenics, racist origins of the birth control and legalized abortion movements have all targeted Blacks as an unwanted population.

• Trump’s anti-illegal immigration stance/policy protects low wage Black workers in the labor market who are being undercut by the lower wages paid to the undocumented. Blacks are being squeezed from jobs they traditionally dominated such as child care, farm work, the hospitality industry, house cleaning, grounds keeping, and construction labor. Cooper argues that before the New Deal, Blacks actually had a higher employment rate than whites, in part, because they were able to sell their labor cheaper. The rise of government support of racially discriminatory labor unions drove Black labor from the market and spiked Black unemployment. It is not in the economic interest of Blacks to support illegal immigration, nor is it in their interest to support minimum wage laws which also drives low wage Black workers out of the market.

• Trump’s support of the Second Amendment helps Blacks who are more likely to be victims of crime because their neighborhoods are more crime-ridden and are under-policed. Considering the history of violence against Blacks in this country, and the difficulty Blacks had in the past with arming themselves, no sensible Black person should oppose the Second Amendment but should rather find the right to own a gun empowering. (Incidentally, this argument is identical to Huey Newton’s defense of Blacks being armed. Newton and the Black Panthers are not mentioned in Cooper’s book, doubtless, because they were Marxists.)

• Trump’s increased funding of the military helps Blacks who are over-represented in the armed forces, especially Black women who are more likely to find supervisory positions there than in any other profession. Even during the age of segregation, Blacks were more likely to re-enlist in the military than Whites, and would have made up a far larger share of the American army had not a 10 percent quota been enforced.

• Trump’s support of law enforcement helps Black neighborhoods that are chronically under-policed. Liberal policies have made law-abiding poor Black people the ones who pay for the crimes committed in their communities as the Black criminal had now become the new victim. As Cooper writes: “To the extent that there is a disconnect between law enforcement and the black community, it has traditionally been for two reasons. First, black leaders in our communities have often sided with the criminal element against the police, acting as if the police were out to target all black Americans rather than black criminals. … Liberal politicians such as Hillary Clinton and former President Barack Obama cynically exploited the fraught relationship between black America and police in a way that further alienated black Americans from law enforcement while doing little to reduce crime rates.” (21) Blacks are now visibly, and in some cases significantly, represented on many big-city police forces and are symbols of authority and order. Having Blacks overly identified with criminals, as White and Black liberals and leftists often do as a sign of resistance and liberation and as some counterpoint to their own boring bourgeois backgrounds, hurts Blacks tremendously, further entrapping them in dysfunctional stigma. (I had a social psychologist friend who told me some years ago that if American prisons were good at producing revolutionaries they would have been closed years ago.)

And so Cooper proceeds systemically with his arguments. Certainly the arguments can be challenged and in some cases probably refuted but overall the book has some heft and is useful if only in confronting a set of orthodoxies and dogmas about Blacks and how they ought to think about themselves politically. You ain’t Black, if you ain’t liberal. You are even more Black if you are a lefty protester, “sacrificing” on behalf of your people. For many Blacks, even those who are not leftist, the left is heroic because it offered an oppositional theory that explained their oppression without blaming them for it and because the left supported Blacks’ challenge for freedom while the right did not. When Jackie Robinson, Black hero that he was at the time, testified against avowed leftist Paul Robeson before the House Committe on Un-American Activities in 1949, even though his objections to Robeson were mild, many Blacks were annoyed, even angered, including Robinson’s teammate Don Newcombe. Robeson was a hero too who spoke truth to power, as many Blacks thought, otherwise why were Whites so interested in discrediting him. This feeling is understandable, even if it can be suffocating and intolerant. But persecuted people love group unity no matter the price you pay for it. They feel they cannot survive without it. But there is tense comfort and even inspiration in the idea that you are Black if you wear the skin and wearing the skin has its demands that you can either submit to or quarrel with but that you cannot escape.

I would not recommend or advocate that anyone vote for Donald Trump (although I have nothing against people who have and am very fond of a few Black Trump supporters I know). A good argument can be made that the Trump presidency has been a failure and we need to turn the page on it. But I believe there is much all of us—pro- and anti-Trump—can learn from hearing from some of the Black people who have voted for Trump or who will; listening to the contrary is what makes the world genuine. There is something else as well, two basic truths: to a considerable extent within the realm of their own beliefs and worldview, people have the right to be wrong, and no one is infallible, which means that everyone is at least partly wrong (though not equally wrong). Over the years, I have appreciated what Black conservatives have taught me, right and wrong, and also what I learned since boyhood from Joseph the Conservator and his brothers.