“And what else?” asked the voice, its owner a dark profile pressed against the grated window.

“Um … I don’t know,” I squeaked. It was only my third confession ever, and I had already admitted scribbling genitalia on my doll with colored pens.

“Have you lied?” the voice asked, giving the verb an extra deep intonation.

“No!” I said, stung at the thought.

“Are you lying now?” the voice thundered.

Well, it sounded like thunder. It may have only been stern. But I count those five minutes in the confessional as my first loss of innocence, because it was the first time anyone ever doubted my word—or thought me capable of something I had never dreamed of doing.

Sin has fascinated me ever since.

We act as though it is immutable, and our definition is God’s own. The Ten Commandments were, after all, carved in stone. The Seven Deadly Sins hang over the heads of the faithful. Original sin was said to stain even the soul of a newborn babe, and if that infant died before baptism, for centuries it was believed to wind up in limbo, suspended in time, unfit to be in God’s presence.

I count those five minutes in the confessional as my first loss of innocence, because it was the first time anyone ever doubted my word—or thought me capable of something I had never dreamed of doing. Sin has fascinated me ever since.

In 2007, the Vatican abolished the notion of limbo.

How we think about sin changes over time—and how it changes reveals quite a lot about us. This is true across many religious traditions, but since Roman Catholicism is a vast repository of thought about sin and its sacramental erasure, I start there, like a drunk looking for keys under a streetlamp, to see how sin has evolved.

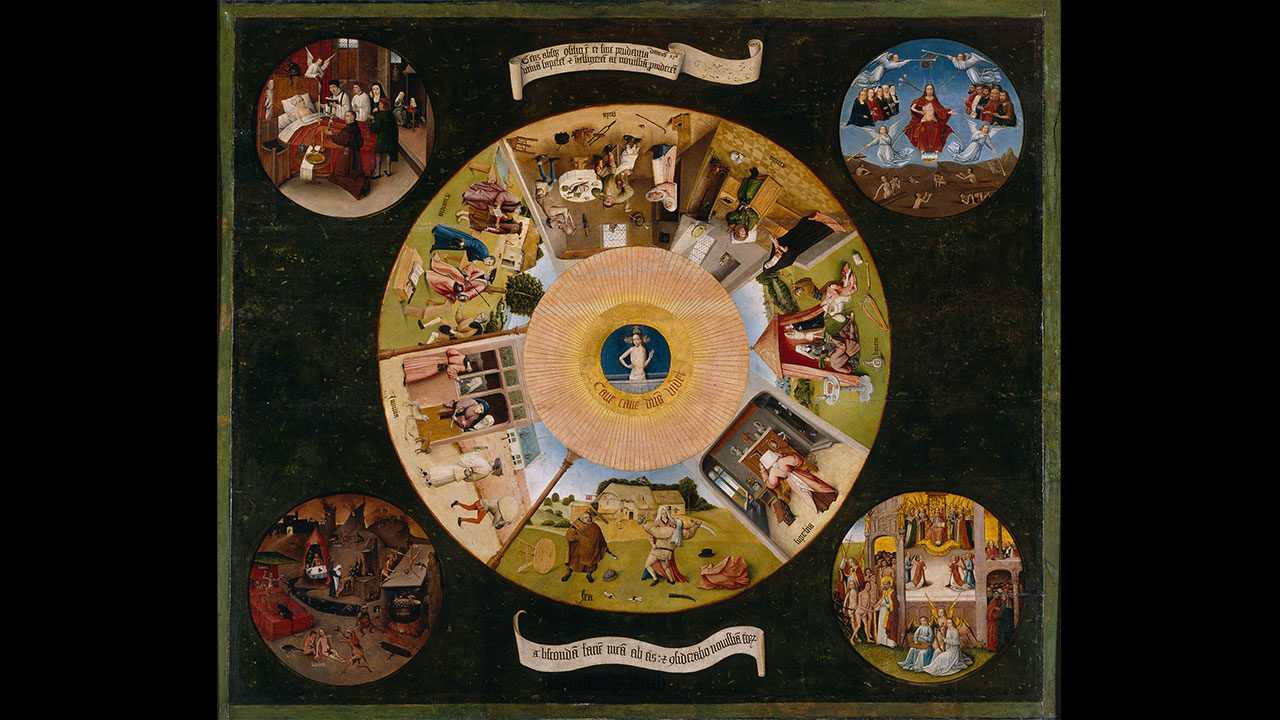

Hieronymus Bosch’s Mirror Image

A man rippling with flesh gorges himself on roasted meat and ale while a gaunt boy begs for food. A woman admires herself in a mirror held by a demon. Two peasants rage at each other, one with a stool already smashed over his bleeding head. Panel after panel, sins circle Hieronymus Bosch’s painted wooden tabletop, the crimsons and ochres glowing. At its center is the eye of God, and reflected in its pupil is Christ, emerging from his sarcophagus to remind us, “Beware, beware, the Lord sees.”

Hell hath its own vignette in the painting’s lower-left corner, and here, all the sinners are naked. Demons poke swords at the wrathful man’s genitalia; a fat toad perches on the proud woman’s nether regions; the glutton dines on slithering snakes; a blacksmith whacks the spine of the slothful dude who preferred his cozy fire to prayer….

Bosch (or one of his apprentices) painted The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things around 1500, capturing the fears and cravings of human nature at the time. Almost 500 years later, in 1993, Susan Dorothea White turned that table, painting the opposites of these sins as equally dangerous. In her Seven Deadly Sins of Modern Times, cool indifference replaces anger, the guy’s designer sunglasses obscuring the plight of the people at his feet. Celibacy replaces lust, workaholism replaces sloth, dieting replaces gluttony; squandering replaces greed … any of this sounding familiar?

Not even original sin holds still, and the Seven Deadly Sins that thread their way through centuries of Western faith, literature, art, and conversation have changed shape, number, order, connotation, and remedy.

White was expanding, and in some ways calming, the notion of sin. When I ask for backstory, she tells me that she does not see the seven deadlies in a religious context, but as “daily habits of extreme behavior that are only detrimental to oneself.” In the Christian tradition, though, anyone’s sin was everyone’s worry. Theologians used elaborate schema to determine which sins were mortal, guaranteeing hellfire to those who did not confess and receive forgiveness.

Those theologians would gape at what passes for “sin” today—or, rather, what passes unnoticed. “Sin is a beast remarkably more supple and complicated than we sometimes suppose,” notes John Portmann in A History of Sin. Not even original sin holds still, and the Seven Deadly Sins that thread their way through centuries of Western faith, literature, art, and conversation have changed shape, number, order, connotation, and remedy.

How political, then, is the definition of sin? Who changes it, and why? And how do those changes shape the way we see ourselves?

Eight—No, Seven—Deadly Sins

Who decides what is sinful? Moses, yes, those tablets. But the seven deadlies? For them, we can thank Evagrius, one of the Desert Fathers and Mothers who lived ascetic, solitary lives in Egypt’s white heat. They were, to steal a phrase from theologian James Alison, “the first psychologists of the spiritual life,” and the first monastic communities soon formed around them.

Evagrius was no stranger to the struggles of will and appetite. Chastened by an affair with a married woman, he fled to the desert in the late 300s. There, he had time to think. As carefully as Charles Darwin would later pin various beetles to cork, Evagrius identified eight categories of evil thought. The sort of thought, in other words, that disturbs a monk in the desert, tempting him away from God. The resulting checklist—gluttony, prostitution or fornication, avarice, pride, sadness, wrath, boasting, and acedia—took hold as a confessional aid. (“The priest’s interrogation was a sort of Kama Sutra,” Alison says dryly. “‘Have you done this? And this? Hmmm, sounds interesting.’”)

Greed introduces itself as retail therapy, a soothing overconsumption that millennials are the first generation in a long while to shove away in disgust.

In the sixth century, Pope Gregory I tweaked the checklist. Reasoning that vainglory (unjustified, blustery boasting) was just another form of pride, he combined the two. He also lumped acedia with sadness, creating a jumbled state of hopeless, purposeless ennui that was later tagged “sloth.” Oh, and he added envy, which perhaps had not plagued monks in the desert as much as it plagued the papal entourage. New total: seven deadly sins.

They were not, by the way, deadly. They could lead to mortal sins, such as adultery, but they could also prompt lesser sins, little bursts of selfishness or self-indulgence. The seven were, in Chaucer’s words, the “chief and spryng of alle othere synnes”—theologically, “cardinal” sins. Today, we define a cardinal sin backwards as one of the seven deadlies, but that is sloppy: “Cardinal” describes a sin that opens a path to other sins, tugging someone farther and farther from God.

So where have these cardinal sins taken us?

In Dante’s purgatory, envy was punished by sewing the sinner’s eyes shut with iron wire. Today, envy propels us up the corporate ladder and keeps us enthralled with celebrities and billionaires. Bred by competition, it creates enemies, and the constant comparing leaves us shallow, insecure, and self-centered. Envy broods and festers into schadenfreude, making voodoo dolls in a dark corner.

Greed introduces itself as retail therapy, a soothing overconsumption that millennials are the first generation in a long while to shove away in disgust. Greed hoards, building a fortress of unneeded stuff or an equally obsessive investment portfolio, none of the trade fair. Refusing to share, greed cancels the pleasure of whatever it fights to acquire. It is as anxious as gluttony—never enough, never enough.

Wrath, I find terrifying, whether it is the Old Testament God who is thundering from on high or a crazy talk show host. This is neurotic: Someone yelling at me cannot, at this late age, undo me. Yet my muscles tighten every time, because someone is sure to get hurt. Wrath offers an illusion of power and a rush of conviction, clearing away all qualms. Congress and the courts have become our coliseums, political protests and city streets our killing fields.

A homicide detective once told me where they look for motive: revenge, passion, or monetary gain. In other words, wrath, lust, or greed. And the arrogance that lets someone premeditate a murder? That would be pride.

We redeem pride’s sinfulness when we are scared, because its lion’s roar of self-aggrandizement looks like strength. But the definition muddies when we turn to our own lives.

Pride topped all the medieval charts, ranked the sin of sins because it was the devil’s own, a diabolical lack of humility that refused to bow to God. It leads to anger, sadness, and “derangement of mind,” warned Evagrius; Spinoza, too, called it “a species of madness.” A more precise name is hubris, and it is the Achilles heel of political power. A 2009 article titled “Hubris syndrome: An acquired personality disorder?” analyzed political leaders over the previous century. “Symptoms” included excessive self-confidence; disproportionate concern with image and presentation; a narcissistic propensity to see the world primarily as an arena in which to exercise power or seek glory; an unshakable belief that they will be vindicated; contempt for the advice or criticism of others; a loss of contact with reality, usually associated with progressive isolation; a tendency to speak in the third person or use the royal “we.”

We redeem pride’s sinfulness when we are scared, because its lion’s roar of self-aggrandizement looks like strength. But the definition muddies when we turn to our own lives. Aquinas said pride could be taken as an inordinate desire to excel—something contemporary society rather encourages. Years ago, I walked by a grade school and saw the first-graders in a circle, taking turns yelling, “I’m great!” at their teacher’s behest. They are in college by now, and being told to market their personal brand, push themselves forward, never take “no” for an answer.

The Absence of Lust

If pride was ranked the worst of sins, lust was initially ranked the mildest. In Bosch’s painting, it is certainly the most appealing. Two couples picnic on soft grass, sheltered by a pink tent, while foolish jesters tease them, lust being folly. For the clergy, though, lust soon became a convenient sin, easy (until recently) to condemn from a high pulpit.

In Lust, philosopher Simon Blackburn is determined to rescue this furtive, headlong sin “from the denunciations of old men of the deserts [and] drag it from the category of sin to that of virtue.” Which would be quite a feat, given the church’s long tradition of treating any sexual sin as grave. Even an impure thought, if you think it deliberately and know it is forbidden, is a mortal sin. The Rev. Kevin J. O’Neil, a Redemptorist priest and moral theologian, wonders if perhaps “so many clergy were struggling with sexuality in their own lives that it took on a significance that was disproportionate.” In the Old Testament, he points out, virginity was not a value; the goal was to be as fruitful as possible. In the New Testament, that began to shift, making celibate religious life the “higher” vocation—which, he says briskly, “is nonsense.”

By surrounding ourselves with explicit images and making all things seem possible at all times, we have exploited our own desires—and it has made both sex and celibacy far less interesting.

We take such ideas less seriously now, unless the lust shows up in Jimmy Carter’s heart or on Monica Lewinsky’s blue dress. Millennials are less interested in sex overall, and their elders are more interested in drumming up a little lust with some internet porn or a purple pill. Evagrius warned his fellow monks about indulging “thoughts of fornication, imagining the pleasures vividly,” but we have built an entire industry on such imaginings. And so much has been made explicit that the thrill of the forbidden has vanished.

I used to drive to a Trappist monastery to soak up the silence, and the very air carried an erotic charge. Energy was being wrenched away from the physical and turned, by a sheer act of will, toward the spiritual, and that alchemy was far more potent than anything explicitly sexual. I do not mean to profane the sacred with this observation; only to suggest that we have forgotten the power of mystery and restraint. By surrounding ourselves with explicit images and making all things seem possible at all times, we have exploited our own desires—and it has made both sex and celibacy far less interesting.

Gluttons for Punishment

Pope Gregory I said that gluttony led to foolish mirth, sneakiness, uncleanness, babbling, and a dullness of understanding. Aquinas added “excessive and unseemly joy,” which to me sounds rather delightful. But as the Romans well knew, true gluttony ends in a vomitorium. A group of French chefs, afraid that stigma still clouded their art, recently petitioned the Vatican for a change in vocabulary, insisting that to be a gourmand was not to be a glutton.

Contemporary society’s relationship with food is…complicated. We use its civilized pleasures to soften life’s hard edges, or we deny ourselves in ways so controlling and ascetic, they seem as sinful as self-indulgence. We have made not gluttony but its consequence the sin, and obesity is written on our bodies and cannot be concealed. A dear friend of mine, unable to lose pounds and pounds of excess weight for physiological reasons, sinks often into depression, muttering that he cannot understand why anyone would want to be friends with him, because he is just “a big fat fuck.” He is not a glutton. But he pays the wages of his supposed sin every time he sees contempt in someone’s eyes.

Sloth is another deadly sin we have turned on its head. The New York Times regularly publishes clever guides for “how to spend your day off,” because, truly, people have forgotten. Sloth’s namesake has become a meme, an emoji we find endearing because our lives feel hyperactive, overstimulated, constantly reactive. Sloths just hang from trees, happy with themselves.

Dante punished sloth by forcing sinners to run continuously at top speed—something many of us now train to do. We think of sloth as “laziness,” but those I hear call themselves “lazy” are really struggling with a lack of confidence and consequent lack of drive—or with exhaustion, depression, fear, resentment, or self-hatred.

Sloth is another deadly sin we have turned on its head. The New York Times regularly publishes clever guides for “how to spend your day off,” because, truly, people have forgotten.

Besides, on the early checklists, sloth was far more complicated than laziness, spanning apathy, boredom, indifference, ennui, passivity, and procrastination. A flat gray, sloth washes color and meaning from the world, and even when it is disguised by a blur of activity, it leaves us feeling hollow and disconnected. The desert monks nicknamed this sin “the noonday demon,” because they were convinced that an actual demon visited them in the hot midday to tempt them into listlessness, dejection, and the neglect of their duties. Today, The Noonday Demon is the title of a book about depression—a clinical condition that can show up as listlessness, dejection, and the neglect of one’s duties.

Sin or Sickness?

In 1902, William James mentioned the handful of preachers who were brushing aside damnation to focus “on the dignity rather than on the depravity of man.”

The trend had begun.

Seven decades later, the introduction to a series in The Times of London noted, “The mildness with which on the whole [the authors] regard the deadly sins may be thought surprising and significant.” By then, therapists had rechristened the seven deadly sins as eating disorders, behavioral disorders, addictions, hoarding, borderline personality disorder, narcissistic personality disorder, clinical depression. Just as an understanding of schizophrenia had supplanted ancient ideas of demonic possession, the damage of bad parenting, trauma, flawed genes, or screwed-up biochemistry was replacing sin. Old notions of shame and guilt were banished as unhealthy; the goal was to cure, not to punish.

In 1960, the Rev. Charles A. Curran, a psychologist, took part in a symposium on the concept of sin and guilt in psychotherapy. He drew lines from sin to feelings of worthlessness, exaggerated self-condemnation, a failure to love, a lack of self-awareness. Albert Ellis, an atheist and one of the pioneers of cognitive-behavioral therapy, took part in the same symposium. He called his presentation “There’s No Place for the Concept of Sin in Psychotherapy” and snapped that talk of sin “breeds sickness.”

We have since learned that wrath can come from a brain without the resilience to tolerate frustration and overstimulation, an ego that cannot tolerate slights, or a mind hijacked by fear. As for gluttony, neuroscientists have found differences in the same dopamine pathways involved with drug addiction. The brain’s reward circuits are underactive, so the cravings cannot be sated. There is a genetic component, and mice with two copies of the gene associated with obesity will eat until they are fat. Are they sinning?

Yesterday’s worst sinners are today’s sociopaths. We speak of milder “sins” as “poor judgment,” “habit,” “self-destructive pattern,” “addiction,” “impulse,” “obsession,” “antisocial trait,” “maladaptation,” “compulsion”…. Neuropsychiatrists are even finding physiological reasons for violent crime: brain tumors, structural differences in the frontal cortex, seizures, abnormal brain electrical activity, low serotonin… The acts of sin are still with us, but the phrase that springs to our lips is “That’s sick.”

The Old Taboos

Some cultures refused from the start to blame the human condition on either sin or pathology. They saw foolish or dangerous behavior and focused on its consequences. When the Black Robes (Jesuit explorers) asked the Cree to translate “sin” into their native language, the elders said the closest word was pâstâhowin—doing something that would shatter your future.

Western Christianity suggested that we were all sinners from the start, and unless we grabbed hold of God, we would burn for eternity.

The earliest sense of wrongdoing was defilement, contamination, the violation of a taboo. “In the Old Testament, anything that is an ‘abomination’ is part of the purity code,” notes Alison, “much closer to our word ‘taboo’ than to a moral wrong.”

In the New Testament, Jesus confronted these purity codes head-on, insisting that only our desires could be impure; that no human person was unclean or inferior. But the old taboos proved as sticky as flypaper.

“Some people still think priests are supposed to be unmarried because having sex might make the priest impure—which is an entirely pagan notion,” says Alison. Levitical notions of blood still wield influence, too: “A friend of mine, a rather distinguished female journalist, had a meeting with the chief rabbi of Great Britain, and she put out her hand to shake his, and an aide immediately struck her hand down, lest she be menstrual.”

In the New Testament, sin was not dirty, the sense that lingers in our language (“the dirty deed,” “doing the dirty,” “dirty language,” “doing someone dirty,” “clean conscience,” “clean living,” “cleaning up your act”). Instead, sin was a loss of connection and relationship. Slowly, with many councils and clashes, that realization would unfold.

But not before Augustine had his say.

“Give me chastity and continence, but not just yet,” the future bishop begged, living “in sin” between ages nineteen and twenty-eight with a woman and their illegitimate child. When he finally converted to Christianity, in 386, he proceeded to ruin every other body’s fun by putting forth a doctrine of original sin that made sex shameful and Christianity smug and exclusionary. Were it not for Augustine, original sin might only have meant colossal stupidity; nakedness only self-conscious vulnerability. But he turned a grabbed apple into a doctrine that held even marital sex to be corrupt, unless used to make little Christians. Even then, the newborn’s soul was said to be stained by the parents’ lust and had to be hurriedly scrubbed clean by baptism.

The earliest sense of wrongdoing was defilement, contamination, the violation of a taboo. “In the Old Testament, anything that is an ‘abomination’ is part of the purity code,” notes Alison, “much closer to our word ‘taboo’ than to a moral wrong.”

Eastern Orthodox churches were not about to accept the notion of sinful babies, let alone the idea that people could be guilty of a sin they did not commit. Soon rebellious western theologians added their own challenges. The Jesuit paleontologist Teilhard de Chardin argued in the 1920s that original sin “simply symbolizes the inevitable chance of evil” that was written into the universe long before humanity existed. (His superiors ordered him to withdraw these words.)

In 1962, Vatican II changed the image of God from “the taskmaster who will throw a book in our faces at the end of our lives and say, ‘Look at all you did’” to “a God who is love,” says O’Neil, calling this “the most important development in nearly a century.” Now full emphasis was on your relationship to yourself, to those around you, to the environment, and to God. No longer would sin require a checklist or an elaborate calculus; if we are paying attention, we know immediately when we have damaged a relationship.

“But I don’t think for a minute that this has been conveyed satisfactorily,” O’Neil adds wryly. Had this new way of thinking about sin-soaked into people’s hearts and minds, he doubts he would hear in confession, “I’m not really sure what to say.” Or, “If Hitler’s not in hell, why am I trying to be good?”

Sex or Violence?

“It seems to me that we have gotten rid of sin,” says the noted biblical scholar John Dominic Crossan. “All we have is inappropriateness. If you come at me for something, I will say, ‘I’m sorry you feel that way,’ or, ‘I’m sorry you were offended by my crime.’ When you ask people about personal sin, it gets more and more trivial. Bad thoughts? You go to a Hollywood movie about the devil, and he comes off as kind of an annoying person.

“The way I come at it is different,” he warns, a lilt of Irish softening the tone. “What is the first time ‘sin’ is used in the Bible? Most people say, ‘Oh, in the Garden of Eden’—but ‘sin’ is not mentioned there. Neither is disobedience, and neither is punishment. So could we leave that aside and look at Genesis 4, Cain and Abel: two brothers, one a farmer and one a herder.” (In a Neolithic context, this makes perfect sense, Crossan notes: “The farmer kills the herder, because herding is a doomed occupation, and the farmer is taking over.”) When Cain decides to kill Abel, “God tells him that sin is crouching outside his tent, waiting to pounce. He could defeat it—there is no sense that sin is something intractable. But he goes ahead. We are expecting of course that a just god will immediately kill Cain. Instead, God marks him.”

This, Crossan says, is the beginning of “escalatory violence,” which he sees as the original sin. “God announces that Abel’s blood has desecrated the ground. Now, if anyone kills Cain, his tribe will retaliate and kill seven times as many people. The desert blood feud has begun. When will anyone really feel safe? Empires must be built…

“I’m not imagining it as some genetic stain,” Crossan adds, “but I’m quite willing to see it as evolutionary.”

I blink. What about the original sin in the Adam and Eve story?

All they were really told, he says, is that there were two trees in the garden, and they could have one or the other—immortality or conscience. “Human beings are allowed to live forever, and then they go for the second tree and get tossed out, but they are tossed out having conscience.” Which is not quite the doctrine of original sin that Augustine later extracted.

“Once he was trying sincerely to be celibate, Augustine couldn’t understand why he could still have an erection,” Crossan remarks, sounding amused and sympathetic at once. “As a Roman aristocrat, you were supposed to be able to control yourself. His interpretation was, One member of my body is at war with the rest of my body. And it all began in the Garden. Our sexuality rebelled against our will.”

After Augustine, Crossan says, “the original sin of the human race has to do with sex, and we have quietly, expertly, and quite deliberately gotten away from the violence. It’s not accidental.” After 300 years of Christianity fighting the emperor, the emperor had converted to Christianity. Now, he was an ally, “and if you start questioning violence, he has the army. So could we talk about something else?” Sex was useful, because it was private. “So this was the deal we made with the state. You handle violence; we’ll handle sex.”

Remembering a similar remark by Alison, I flip back in my notebook: “You quite frequently had bishops and priests taking part in the wars of the time,” he said. “When commercial life took over cities, you started to get the battles about usury. They finally gave up on controlling usury, and you see a pulling back to the area they think they can control: women, women’s bodies, and sexual matters. And finally even that became too stupid to take seriously, and everyone had to reinvent the whole thing.”

While my mind was drifting back to sex, Crossan was talking about the addictiveness of violence. “It almost blows your mind to try to imagine a world without it,” he says. “Civilization has solved the sloppy violence of barbarism by getting it all organized, but competitive brutality runs awfully deep in our culture—and the taste for violence threatens our species. I want to start there with sin. With less emphasis on the peccadillos of this person or that person.”

After Augustine, Crossan says, “the original sin of the human race has to do with sex, and we have quietly, expertly, and quite deliberately gotten away from the violence. It’s not accidental.”

Still, the seven deadly sins do concern him. “Maybe we have to retire the word ‘sin,’” he suggests. “I’m afraid sin is almost becoming a matter of taste. We trivialize it by saying, ‘You shouldn’t be watching this or thinking that.’ Meanwhile, our species is part of a giant evolutionary experiment. It’s as if a family said, ‘Let’s give our ten-year-old daughter the keys and see if she learns to drive before she kills herself.’

“There’s this vision in the Bible that on the last day, there will be a great judgment of the entire human race,” he adds. “If you take it literally, I think it’s absurd. But on an evolutionary plane, everyone who has ever lived has moved that judgment one way or another: toward whether we will destroy ourselves as a species or whether we will survive.”

The Future of Sin

Crossan is not alone in taking sin to another level. After Vatican II, liberation theology began to prod the Catholic conscience, pointing out how U.S. corporations, corrupt governments, and unequal structures were destroying lives in Latin America. Phrases like “institutionalized violence” forced the church to stretch the traditional meaning of sin, proving what Jesuit theologian Michael Sievernich calls its “plasticity.” Suddenly we were all responsible—and though resisted by conservatives, that mindset has expanded.

Once hidden in a dark-curtained confessional, sin now floats around the globe. The danger is that, while the old, personal notion of sin was hot and messy and vivid, this sort is cool and abstract. Instead of dwelling on intimate, shameful failings, we scan the horizon for sins so vast, it is hard to point blame or feel their full weight (unless you are one of the victims). Those of strong conscience dive into the struggle, and the rest of us watch from the sidelines, awkward bystanders not sure what is expected from us. Sexism, racism, poverty, homophobia, exploitation or neglect of anyone who is vulnerable, religious intolerance, waste, overconsumption, cruelty… We are complicit if we watch in silence; if we help shore up these structures; if we rationalize their existence.

The seven deadlies may have been tweaked and even turned upside down, but they have not vanished. The real change is that we are no longer sure what to do about them.

If people still went to confession, the lines would be long. But those dark velvet curtains barely rustle. This has worried quite a few popes and moral theologians: What if passion about the world’s injustices distracts us from our personal sins? The seven deadlies may have been tweaked and even turned upside down, but they have not vanished.

The real change is that we are no longer sure what to do about them.

In 1992, an article noted that “the concept of sin seems to have virtually disappeared” from spiritual counseling. In 2004, a BBC survey asked if the seven deadly sins were still relevant, or modern sins had taken their place. A majority of respondents named the deadliest sin as cruelty, followed by adultery, bigotry, and dishonesty. Of the original seven deadly sins, only greed received any nominations at all.

Then, in 2008, just as sin seemed to have vanished from the horizon, Bishop Gianfranco Girotti announced seven new mortal sins: destroying the environment, manipulating genes, becoming obscenely wealthy, creating poverty, trafficking drugs, doing immoral scientific experimentation, and violating the fundamental rights of human nature.

That same year, Barack Obama called racism the original sin of the U.S. Portmann had just published his History of Sin, in which he argued that the very idea of sin was making a strong comeback: He called racism the most obvious of modern sins, then added obesity, depression, failing to thrive, harming children, wife abuse, sexual harassment, denying the Holocaust, homophobia, and drunk driving.

In 2015. a Pew Research Center study found that more than three-quarters of all U.S. adults still believe in the concept of sin, but the old consensus about what is sinful has fallen apart. Abortion? Birth control? Homosexual behavior? Buying luxury goods without giving to the poor? Living with a romantic partner outside of marriage? Overusing electricity and gasoline?

Personal sins are harder to calculate these days. Social sins leave us feeling helpless. And the new sins are complicated. Are biotechnology and global finance just handing new costumes to old desires, or are there really entirely new ways to sin?

“Well, absolutely, and you could go on forever,” says O’Neil—who would rather not. He shudders at the thought of yet another checklist. We should be deepening and righting our relationships with God, other people, ourselves, and the environment, he says. Instead, we are stuck somewhere between legalism and paralysis.

The paradox, he adds, is that “the modern world, with its prioritization of reason and will, actually made us all much more moralistic than the medieval world. They were into virtues, which are habits of living rightly. That’s much different than a world in which an individual is having to make constant decisions about what to do.”

Theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer talked about “cheap grace,” the sort we bestow upon ourselves when we know full well that we did something wrong but do not want to repent. We hear bids for cheap grace in the forced public confessions of corporate executives, celebrities, and politicians. I hear them in my conversations with myself, every time I shrug off guilt and negotiate my own forgiveness.

Evagrius would never dare. How different those seven sins must have felt in the desert. The pride of the insufferable monk who could not laugh at his flaws or obey his abbot. Gluttony, a real danger, because food supplies were limited. Lust, a threat to group peace. Wrath, bound to trigger grudges or reprisals a small isolated community could not withstand. Greed, the exact opposite of communal life. Envy, a breeding ground for petty malice that could make life unbearable. Sloth, the negation of the love they had hoped would bind them together.

Theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer talked about “cheap grace,” the sort we bestow upon ourselves when we know full well that we did something wrong but do not want to repent. We hear bids for cheap grace in the forced public confessions of corporate executives, celebrities, and politicians. I hear them in my conversations with myself, every time I shrug off guilt and negotiate my own forgiveness.

For me, sins are not devil thoughts, just luxuries that backfire. I can nobly turn my attention to world problems and ignore them altogether. But that means I also have to ignore Pope John Paul II, who insisted that social sins were rooted in personal sins. Beneath all the isms and oppressions and high-tech manipulations, he saw pride, avarice, a sort of gluttony, an envy that fuels competition, a sloth that sees no deeper purpose to life. Structural evils are personal sins writ large—and exponentially more destructive.

Juggling private and public sins and their old and new definitions is exhausting, and I am about to give up (which would be sloth) when I come upon Gandhi’s extraordinarily balanced, contemporary version of the seven deadly sins. What will destroy us, he said, is “wealth without work, pleasure without conscience, science without humanity, knowledge without character, politics without principle, commerce without morality, and worship without sacrifice.”

Any of those seven could be deadly.