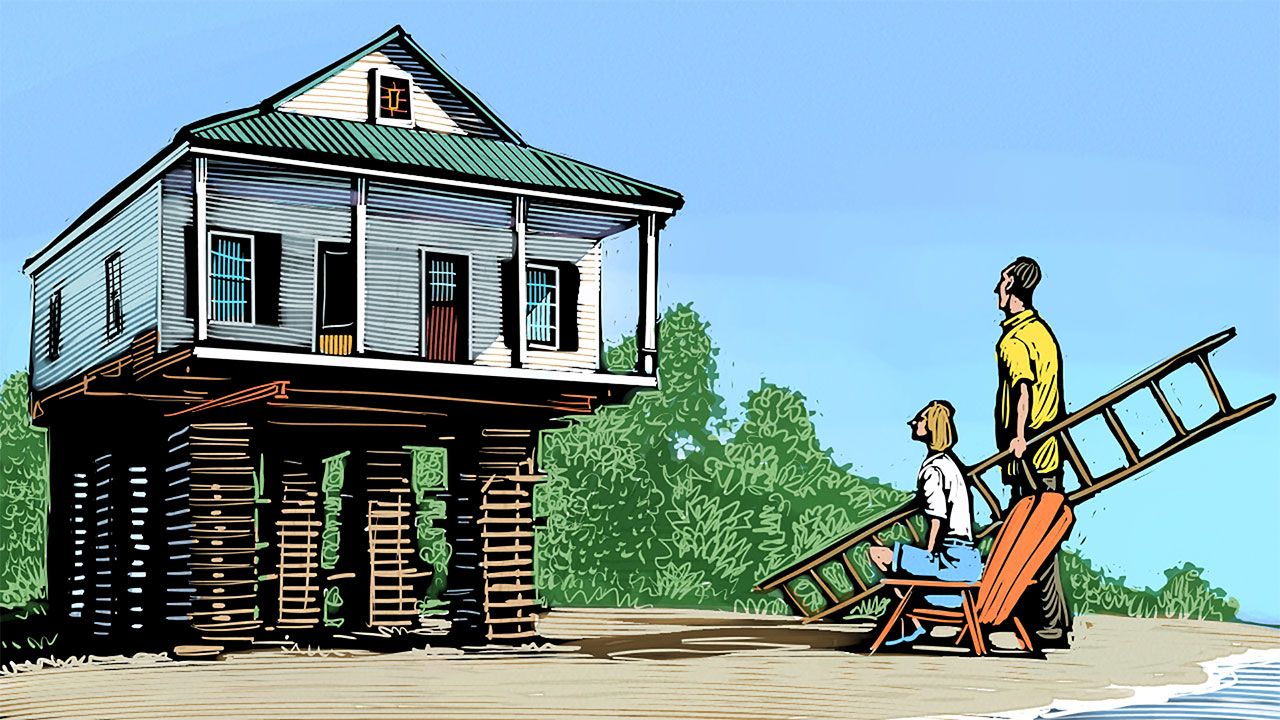

My family owns a house in Lake Charles, Louisiana, 30 miles from the Gulf. In May we got a letter from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), saying they planned to raise our house several feet in the air to mitigate future flooding. This would mean first digging a void under the house; cutting electricity, gas, water, and sewer; felling trees and ripping away decks; then lifting it on its slab with jacks; shoring it up with piling or replacing the dirt or both; reconnecting the utilities; and re-landscaping the property, including carving a new driveway that would now rise to the house from the road.

All this was meant to be the good news. But it was our decision in the end, the Corps said, and we might want to attend one of the informational meetings they would hold for the owners of 3,462 such structures in three parishes of southwest Louisiana.

The proposed cost to taxpayers for what they had in mind in our little corner of the state, near Texas: three billion dollars.

Similar projects proposed for the rest of coastal Louisiana would bring the total to 70 to 115 billion dollars (estimated in 2009). Despite these alarming figures, the USACE’s Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Final Technical Report warns that “absolute protection is not possible. This report has adopted the term ‘hurricane risk reduction’ rather than ‘hurricane protection’; presents plans in terms of residual risks; and contains statements throughout that 100 percent risk reduction is not achievable.”

• • •

We bought our house because it is in a good neighborhood in the supposedly right school district, and we liked its style: Low and cool, with cypress woodwork, a couple of small courtyards, and a side deck. In a town full of “executive-style” and Acadian vernacular houses, it was unique, had plenty of room for our family, and would permit us to host parties expected in my new job. This, we believed, would be our home into retirement.

Over time we would learn what was normal in Lake Charles and what was considered unusual.

There were weird problems before we even closed on it. The seller hallucinated that my wife was at her door when we were several states away. Our corporate bank, which helped cause the subprime crisis, strung us along for weeks to make a show of responsibility with new mortgages. A named tropical storm slipped into the Gulf right before signing; insurance will not write a house policy when this happens. But we finally got into the house.

Over time we would learn what was normal in Lake Charles and what was considered unusual. Louisiana gets five feet of average annual rainfall, more than any state except Hawaii, so residents of Lake Charles are used to streets flooding, even in thunderstorms. Cars stall out, and manhole lids geyser. The street into our subdivision sometimes disappears, and the drainage ditch along the main road turns into a Class III rapids that rises into the yard. An hour after the rain stops, the water recedes. The house remains dry.

But after we had lived here a while neighbors began to tell us, with that awkward but satisfied look when reporting others’ disaster, that our house had flooded more often, and worse, in hurricanes than the seller had disclosed—as much as four- to six-feet deep a couple of times. It is also what is called here a hurricane house—damaged so badly in the past that insurance paid to replace the roof, drywall, insulation, floors, cabinets, appliances, and probably the wiring. It was listed as having been built in the ’50s but was evidently gutted and rebuilt in 2005, after Hurricane Rita, and repaired again after Ike, which were the most recent Katrina-like events of southwest Louisiana.

(After hurricanes, roving crews of workmen repair homes if you can pay cash on the spot; everyone else must wait weeks, months, or years for insurance to pay. This leads to quirks obvious in hurricane houses, such as a single paint color used on all interior walls, because that is what that crew had, or expensive windows, bought in bulk, with nary a screen to make them operable in cool weather.)

Our realtor admitted Lake Charles “looked like a bombed-out third-world country” after Rita. Later we learned about the coffins that popped loose from the earth and got hung in the trees, the cattle that went mad from drinking brackish [water] and had to be shot, and the mass graves in town for victims of Audrey.

The severity of those storms also explains why all the trees in the neighborhood lean 10-degrees off vertical in the same direction. Our realtor admitted Lake Charles “looked like a bombed-out third-world country” after Rita. Later we learned about the coffins that popped loose from the earth and got hung in the trees, the cattle that went mad from drinking brackish and had to be shot, and the mass graves in town for victims of Audrey.

The problems associated with development on this coast are only getting worse, due to subsidence, sea rise, and population density. “Serving the engineering needs of south Louisiana is a task so monumental that it can only be performed by the U.S. Army,” says the USACE.

• • •

I used to work for the Army Corps of Engineers. That is, when I was a 19-year old soldier, my Military Occupational Specialty was 12B, Combat Engineer, then 00B, Engineer Diver, both of which fell under the authority of the Corps. Essayons—Let Us Try!

In the military sense, the USACE is a Direct Reporting Unit to the Department of the Army, organizationally different from the Army Service Component Commands that we think of as “the army”— infantry, armored, and other divisions. None of that matters much; engineer soldiers train, go to the field, and get deployed like everybody else.

But that is only part of what the USACE does. On the governmental-civilian side of things, they build and maintain infrastructure; research and develop technology; dredge America’s waterways and provide recreational facilities; protect and restore the environment, including contaminated sites; and devise “hurricane and storm damage reduction infrastructure.”

In all, the USACE has 37,000 civilians and soldiers in 130 countries. Its “Civil Works” program is budgeted for almost $5 billion in fiscal year 2020, which “reflects the Administration’s priorities for water resources infrastructure,” the Assistant Secretary of the Army for Civil Works says.

A former high-ranking official in the Office of the Chief of Engineers and Commanding General at the USACE Headquarters spoke with me about civilian works. He said the Corps “essentially works for FEMA,” since much of the funding in FEMA’s Emergency Support Functions goes directly to the Corps.

“The Corps of Engineers builds nothing,” he said. “They administer.” That includes massive projects such as the Hurricane and Storm Damage Risk Reduction System in Louisiana, authorized and funded in 2005 after Katrina and Rita. It forms what the Corps calls a 133-mile “perimeter system” of armored “levees, floodwalls, gated structures and pump stations” around the Greater New Orleans area, as well as 70 miles of “interior risk reduction structures.” Its budget was $15 billion; most of the contracts had been awarded as of January 2018.

“It’s crazy as hell,” the former official said.

None of the budget for FY 2020 is appropriated for house-raising in southwest Louisiana. That will be extra, in the future, if the President asks for it and Congress approves.

• • •

Louisiana, like me, makes bad choices and suffers by them. Instead of envisioning the Gulf of Mexico as, say, the American Mediterranean and protecting the coast for its bankable beauty and renewable resources, Louisiana took the short money with petro-development. As a result, it ranks worst for pollution among all states by US News, and (as always seems to happen with oil economies) corruption is rampant. Karma starts to seem veritable when climate change affects such a place.

This coast has always been vulnerable to storms, because it is low, flat, and made of clay and silt, not bedrock. Engineering projects meant to improve human chances on the Gulf, such as controlling the Mississippi or digging drainage canals, have actually led to more fragility.

The state is sinking into the mud and is being covered by the rising sea faster than almost anywhere else on earth. Since the 1930s, the equivalent of 25 Washington, DCs, have disappeared. Satellites show what few want to see: the lower part of “the state of Louisiana” is actually an unusable, uninhabitable lacework of water and mud. If New Orleans, in its bowl, is to be saved permanently, the Corps will likely have to take more radical, Netherlands-style measures at terrific additional cost.

Engineering projects meant to improve human chances on the Gulf, such as controlling the Mississippi or digging drainage canals, have actually led to more fragility.

Louisiana has often served as a bellwether for national problems—in politics and higher education, and with guns and climate change. If anyone wanted to see what happens when corporations are allowed by government to profit without true accounting, they could look to Louisiana, where companies make their money and leave behind problems such as collapsing or polluted salt caverns, oil leaks, toxic waste, and those drainage canals that weaken the coast and kill wildlife.

Of course, not just the guilty are harmed, and not just in Louisiana. The USACE says:

“The rapid erosion of Louisiana’s coast puts some of the nation’s critical assets and natural resources at risk. The southern coastal area is home to nearly half the state’s population, one-third of the fish (by weight) commercially harvested in the lower 48 states, and five of the 15 busiest ports (by tonnage) in the United States. In addition, nearly 25 percent of all the oil and gas consumed in America and 80 percent of the nation’s offshore oil and gas travel through coastal Louisiana. As wetlands erode, the infrastructure that transports the nation’s energy supply becomes increasingly susceptible to storm damage.”

Above all, what the attempts at flood remediation in south Louisiana highlight are the tensions of recent populism in America, which thinks it wants small government and no regulation, until disaster occurs. (The region where I am from in the Midwest has in recent decades decried social safety nets and “government interference” but would have starved to death without FDR’s New Deal.)

What if the money and effort were used to move everybody to higher ground and start over? Raze, not raise? Central Mississippi seems to have a lot of open land.

Time is short for Louisiana, with consequences of bad choices coming faster and costs mounting. These pressures mean new, possibly shortsighted solutions will be found, which may include some of the biggest public-works projects in our history, yet will not solve the underlying problem.

The “Planning Unit Boundary” of the USACE for this project, after all, is north of Lake Charles, on a line with Baton Rouge. It shows where problems occur now, even before climate change worsens. Yet south of that boundary is where heroic measures are planned. What if the money and effort were used to move everybody to higher ground and start over? Raze, not raise? Central Mississippi seems to have a lot of open land.

• • •

For six of the seven years we have owned this house, I have told friends I hoped the next hurricane would just wash it off its slab into the sea—after we were safely north, of course. I would have liked to hear “buyout” at the USACE meeting.

I also knew this would never happen, even if it saved the feds and state money; even if raising the house cost them more than what was left on our note; and even if the “fix” of raising would perpetuate habitation where it made little sense and cost everyone money. People think they cannot stand to lose what they are used to.

There was a large crowd of homeowners in the meeting room at the Lake Charles Civic Center in June. The Corps sent a presenter and a technician, and there were several representatives from the Calcasieu Parish Division of Planning & Development and the state Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority Board (CPRAB).

The two main speakers at the meeting were Darrel Broussard, Senior Project Manager, USACE New Orleans District, and Carol Parsons Richards, Coastal Resources Scientist Manager, CPRAB. This particular project, for the three parishes (counties) of southwest Louisiana, had been going on since 2006-07, they said. It had evolved from a series of other proposals now abandoned.

One of these was to build a 12-foot seawall/levee across the entire bottom of the state, nicknamed “the Great Wall of Louisiana.” (The former USACE official knew about this, of course, but shouted into the phone at me, “That’s crazy as hell!”) Another would have been to encircle the most threatened urban areas, essentially making Lake Charles a medieval fortress town. (“Nuts!” the former official told me.)

Time is short for Louisiana, with consequences of bad choices coming faster and costs mounting. These pressures mean new, possibly shortsighted solutions will be found, which may include some of the biggest public-works projects in our history, yet will not solve the underlying problem.

Levees were considered a “structural” solution, since they would have to be built, while raising existing structures was the “non-structural” alternative. Because it was so expensive to build stable levees that would not be easily flanked or topped by storm surge, non-structural solutions, the USACE had determined, had a 5:1 benefit-to-cost ratio.

Eastern Louisiana (meaning New Orleans and the River) had gotten federal funding more easily, they said, because so many projects were already there. But now it was southwest Louisiana’s turn—or would be, they hoped, since only $800,000 was actually funded for now, out of $3 billion appropriated. The $800k would be for engineering-and-design only.

Broussard said 62,000 structures had been identified originally as candidates for remediation. The USACE sent surveyors out for “windshield” inspections, to get “eyeballs on structures.” They did not go on private property or inside houses, and the cursory inspections were not correlated with National Flood Insurance Program or other FEMA data. Broussard said they would rely on homeowners “to do the legwork,” and current flood certificates could be used to help determine the priority of being raised. He was careful to repeat that storm-surge flooding—not riverine flooding or storm-drain backups—was the qualifying event for a house to be raised.

In the end, only 3,462 structures would be raised, from six inches to 13 feet above Base Flood Elevation (BFE). (Above 13 feet, the houses became a wind-damage risk.) Three-hundred forty-two commercial or public structures would be “dry floodproofed” up to three feet. Berms would be built around 157 warehouses. Five areas were designated for shoreline protection, and 7,900 acres of wetland would be restored.

During a question-and-answer session after the presentation, an audience member asked if work would be done by the Corps or by contract. Jokes instantly flew about lowest bidders doing incredibly sensitive work. Would they crack a family’s home in two?

However, the plan for now was to do full surveys for only 50 to 100 “priority homes”—those at the lowest elevations, which already might flood as much as five feet—in the summer and winter of 2019. The Corps was “doing all the legwork up to awarding a design-build contract,” so future funds could get used in good time, but again, no one could say when or if the rest would come. Darrel Broussard hoped the Corps might be given $45 million per year, to raise 200 homes per year, in a 20-year plan. The audience murmured, as if that was both too slow and unlikely.

During a question-and-answer session after the presentation, an audience member asked if work would be done by the Corps or by contract. Jokes instantly flew about lowest bidders doing incredibly sensitive work. Would they crack a family’s home in two? If so, who paid for the damage?

Broussard said the USACE would not do the work; they solicited companies by Multiple Award Task Order Contracting (MATOC) and would pick the best, not the cheapest, to do the work. It was not a grant program, he said. The state and the Corps, not the homeowner, would oversee the quality of the work, and the Corps would have an inspector onsite during raisings “to reduce the oops” factor.

The “oops” was a big hit for nervous homeowners, and they repeated it and thought to ask what difficulties were involved in raisings. All the officials agreed that the process was straightforward and relatively painless, that it took just one to two months, and homeowners must be out of their homes for only a week or two, when utilities were disconnected. A tart elderly woman asked if she would have to move out all her stuff (“nope”) or take her pictures off the wall (“nope”). The only thing she would have to do, an official said, was take the food out of her fridge, since it would be shut off.

“I’m ready now!” she said.

One man said he was not sure he liked the government coming in to tell him what to do with his own property. Broussard explained again that, as they had said in their letter, and on all the materials, and earlier in the evening, the program was 100 percent voluntary. The man caved and said of course he wanted to be taken care of with everybody else.

A Calcasieu Parish Division of Planning & Development employee took the chance to say that the National Flood Insurance Program was subsidized by the feds now but would be going fully actuarial soon, so rates would probably go up and would be aligned more accurately with risk. The USACE house-raising project was a good thing, she assured everyone, as she and the other officials began to try to end the meeting.

“It should improve property values,” she said.

“Only in the long run,” someone countered. “Very long.”

Darrel Broussard admitted that the project was “first of its kind,” in this area, for the Corps and the state, so there were “lots of eyes on it.”

“Gonna be a little bit of growing pains,” Carol Richards said gently.

Broussard said a south-central, Louisiana-coast study was just getting underway, so southwest Louisiana was “years ahead” on a problem that many other places in the country will face.

As the meeting broke up with no hope for quick action, the couple in front of me sat talking about the start of hurricane season (June 1), and how sea-level rise made storm surge worse. They laughed at how President Trump used “act of God” clauses to get out of his troubles. (His lawyers argued that the 2008 recession was an act of God, because former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan had called it a “tsunami,” so Trump should not have to pay back Deutsche Bank for a large loan.) The couple joked with each other that maybe they could claim global warming as an act of God, to rid themselves of their house before the next big one hit.

If the Louisiana coast has a cursed quality, it is not at all clear that God is to blame.