“If they don’t care, the hell with them.”

—Robert Kennedy, responding to an aide who wanted to know if he wanted to give another campaign speech about poverty in America before an indifferent college audience

“He was this younger brother full of pain.”

—New York City activist Sonny Carson, speaking about Robert Kennedy ¹

- The Fire . . .

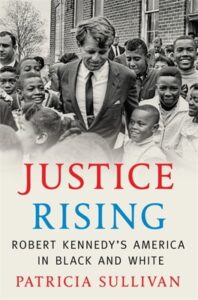

It is unclear whether Senator Robert Kennedy (D-NY) would have won the presidency in 1968. He had a number of things going for him. First, he was young (42 years old), slim, handsome, and energetic. Second, he was the brother of a young slain president with whom he was closely identified. The combination of these two factors made him charismatic, more a celebrity than a politician. It also tinged him with tragedy, so he seemed for many to have been tempered in a forge of shock and sorrow, buffeted by the violence that then seemed to be unhinging the country in a way that made him both tough and vulnerable. As Patricia Sullivan writes about his campaign, “There was no entourage of advisors, pollsters, and media analysts traveling with Bobby. He was spontaneous and impulsive, and he made important decisions himself.” (396) He seemed the lone wolf, rootless yet territorial, the inspired improvisor able to play any chance; for his admirers, he was authentic. His wiry energy, his kinetic ruthlessness seemed to mirror the velocity of the age he lived in.

The large, fervent crowds that greeted him on the campaign trail, as Sullivan describes them in Justice Rising, acted as if he were a celebrity, a Hollywood star, even a messianic figure, the wounded hero, rather than a politician. In part because of his martyred brother, in part because of his own intense interest in racial matters, Kennedy had such purchase with Black audiences that he was likely the only White person in America who could have gotten away with speaking to a mostly Black gathering at a subdued and abbreviated political rally in Indianapolis just a few hours after Martin Luther King’s assassination. “For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and mistrust of the injustice of such an act, against all white people” Kennedy said to the crowd, “I would only say that I can also feel in my own heart that same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man.” (414) Black people accepted that Kennedy honestly knew how they felt. Even though he was the scion of a rich Irish Catholic family, Blacks felt that Kennedy understood suffering, had even suffered on their behalf as his brother, President Kennedy, had pushed for new civil rights legislation. Perhaps that is why John Kennedy was killed, as some Blacks thought. From their perspective, Whites had resorted to the use of any kind of force, even murder, to keep Blacks in their place.

He was, as we learn in Justice Rising, the intersection of the two mass protest movements of the moment: the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement. He became a voice for both, while never being a direct participant in either.

Robert Kennedy’s other advantages were that he was an effective, tireless campaigner, and he was running in an especially turbulent time in America when many people wanted change and he seemed so obviously a change agent. He was, as we learn in Justice Rising, the intersection of the two mass protest movements of the moment: the civil rights movement and the anti-Vietnam War movement. He became a voice for both, while never being a direct participant in either. He seemed the political insider who was able to connect with the outsiders, those who were disappointed in America. While he could sympathize with those who felt betrayed by America, he himself never lost faith in the country, when, of course, he could have, justifiably so. This duality of Kennedy, his sincere identification with those who felt this a failed nation, stumbling and brutal at the height of its power, and his ever-abiding faith in what the country stood for, its exceptionalism, if you will, was what probably attracted historian Patricia Sullivan to this project. Kennedy is the only White American of the 1960s who came close to MLK in this regard of keeping in balance what the United States was and what it could be.

• • •

- Next Time

But Kennedy had a number of things going against him. First, he was running an insurgency against an incumbent president of his own party. Almost no party can ever survive such a fracture in an election year, even if, as is the case here, the incumbent, Lyndon Johnson, eased some of the pressure considerably by deciding not to run again. Kennedy’s brother, Ted, ran an insurgency against a sitting president of his own party in 1980, Jimmy Carter. Ted did not win the presidency or even the nomination, but he did so divide his party that Carter did not win the election. In fact, it took the Democrats twelve years to recover and win the presidency again. Intraparty insurgencies cause lots of lasting bad blood.

(Senator Eugene McCarthy (D-Minnesota), running as an anti-Vietnam War candidate finished second in the 1968 New Hampshire primary—the common misconception is that Johnson lost the primary, which he did not—and this chased Johnson from the race. Kennedy entered the race after McCarthy’s success in New Hampshire—and was criticized as an opportunist for it—but before Johnson announced that he was retiring. This has led many to think that Kennedy’s candidacy was the true coup de grâce for Johnson, that Kennedy frightened Johnson from the lists. But not so for Lady Bird Johnson, Lyndon’s wife, who feared that Kennedy’s entry would make her husband stay in the race, if only to beat him any way he could because he hated Kennedy so much.² She was relieved when Johnson announced he would not run.)

There was also the question of Kennedy’s appeal. Kennedy had become so associated with Blacks and the poor that it was uncertain how deep or committed his White middle-class constituency was. He was hated in the Confederate South, for instance, for his time as Attorney General and his enforcement of Brown v. Board of Education in the integration of the University of Mississippi which Whites protested violently, and the University of Alabama. In the late 1960s, an era of violent urban race riots, disgruntled, militant Blacks shouting Black Power and who seemed to hate the country, it was a real question to pose: How would centrist, suburban Whites vote?

The Republican Richard Nixon won as the “law-and-order” candidate. Vietnam, as it turned out, did not matter very much. Domestic politics dominated the election, especially after Johnson decided not to run as the Vietnam War was mostly associated with him. Perhaps if Kennedy had lived, he would have won the nomination. Perhaps he would have beaten Nixon who might have been unnerved at the prospect of running against the brother of the man who defeated him for the presidency in 1960 and who was subsequently assassinated. Perhaps Kennedy would have gotten a large sympathy vote, many feeling the country “owed” him the presidency because of his brother. Perhaps “law-and-order” won because Hubert Humphrey, the Democratic nominee and sitting vice president, was too compromised a voice to argue effectively against it. Kennedy would not have been so compromised in supporting the Johnson administration because he was running against it as an insurgent candidate. Perhaps Americans—even many African Americans—were simply exhausted by chaos, and bad, hypocritical order, after all, is better than no order at all.

Kennedy had become so associated with Blacks and the poor that it was uncertain how deep or committed his White middle-class constituency was.

As Sullivan writes, “Kennedy viewed the Democratic Party as too beholden to interest groups that had become insular and power-driven, largely irresponsive to the political energies that had been unleashed over the course of the previous decade—among youth, African Americans, the poor, and those suburbanites who wanted action on social problems.” (400) Of course, this was the party that, under Johnson, had given America the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Medicare, Medicaid, Model Cities, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Endowment for the Arts; so, it could be said that the party’s sweeping public policy initiatives were both cause and effect, responding to the activism while generating more of it. Maybe Kennedy was moving faster than his party in seeing a major political realignment, while the political machine was unable to absorb or even understand the changes it was partly responsible for spawning. Who can say? Robert Kennedy did not become president because he was shot to death by an assassin in June 1968, right after he won the California Democratic presidential primary.

• • •

“He was more than a junior senator from New York. He was a folk hero, a pop icon, a symbol of political opposition and glamorous royalty; he was his brother’s brother, and his family’s heir, and his party’s prince.”

—Jack Newfield, “The Day of the Locust” ³

- Your mission, should you decide to accept it . . .

Justice Rising is a magisterial book by a master historian, an epic sweep of Robert Kennedy and his time as a public figure. It is not a standard biography, but it has the narrative drive of a good biography. There is precious little here about Kennedy as a father, a husband, a son, just a few bits. Much testimony but little gossip. Yet one learns a great deal about Robert Kennedy person as well as Robert Kennedy the politician.

There is much here about his relationship with John but that is because he worked as his brother’s campaign manager in 1960 and worked in his administration as attorney general. In exploring that relationship, the book is surely informative and, at times, even moving. John came into the presidency determined to be more proactive about civil rights. His party’s civil rights platform plank in 1960 was its strongest ever. He had done well with Black voters in the 1960 election. “[John Kennedy] pledged, if elected, to employ executive action in support of civil rights,” writes Sullivan, “and said he would host a series of conferences to create a climate of compliance with the Brown ruling.” (75) He wanted someone he could trust as attorney general, someone who would push for civil rights, and he felt the only person who could do this was Robert, who did not desire the job, taking it “reluctantly,” as Sullivan writes. (81) He was 34 years old. Others in the cabinet could be trusted or not-so-trusted associates, but the attorney general had to be John’s right hand. Robert chose to accept the mission.

As Sullivan relates, Robert Kennedy transformed the Justice Department, bringing in young lawyers, most under 40, who were determined to change things. No more business as usual. The White South was dragging its feet, obstructing in every way fair and foul, legal, illegal, and violent, the implementation of Brown. Kennedy’s Justice Department’s mission was to make the South conform to Brown with all the power at its disposal. Kennedy developed “a reputation for getting things done.” (195)

What Sullivan’s book makes clear is that Kennedy was a learner. He spent hours talking to civil rights activists, or rather having them talk to him. Some of these meetings, such as the famous May 1963 encounter he had with James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Kenneth Clark, Lena Horne, Harry Belafonte, Edwin Berry, Clarence Jones, and Baldwin’s brother, David, as well as a young activist named Jerome Smith did not go well.

What Sullivan tells here is the story of the creation of the Second Constitution. The original Constitution guaranteed complete freedom of association and limited federal power. The 1930s gave us greatly expanded federal powers with the New Deal. The 1960s, with the civil rights revolution, brought the end of state-sanctioned discrimination, of the nation’s tacit understanding that the race problem or the Negro, as Black folk were so quaintly referred to, being the sole domain of and under the complete discretion of the White South. Negroes were determined to be at no one’s mercy or endure anyone’s forbearance anymore, least of all at the mercy of people who hated them, and for the first time there was a Justice Department willing to support the Black desire for full citizenship, which meant an end to White domination. Kennedy thought the power of the federal government should be used to force compliance with this new order of a pluralistic society. Brown, in effect, created a new America. For a time, the Justice Department, under Robert Kennedy, seemed an arm of the civil rights movement, a supporter of the activists.

What Sullivan’s book makes clear is that Kennedy was a learner. He spent hours talking to civil rights activists, or rather having them talk to him. Some of these meetings, such as the famous May 1963 encounter he had with James Baldwin, Lorraine Hansberry, Kenneth Clark, Lena Horne, Harry Belafonte, Edwin Berry, Clarence Jones, and Baldwin’s brother, David as well as a young activist named Jerome Smith did not go well. Kennedy felt he was simply being harassed and harangued at as the participants let loose with their feelings, candidly telling him about their disgust with the country and their refusal to put up with the current situation. Kennedy left the meeting frustrated, thinking that the participants did not understand how government or politics worked, did not understand how to talk to him in a way that could be helpful. He preferred talking to King any day of the week. King knew politics. With the passage of time, Kennedy came to appreciate the meeting more and to understand why the participants spoke the way they did. Angry Black people were justified in their anger, he came to realize.

He also spoke to academics, students, businesspeople, community activists, and ordinary citizens. He traveled in Black rural Mississippi, among the poor Whites of Appalachia, and through Watts and Bedford-Stuyvesant. “Kennedy was a rare person in the upper echelons of political power and influence: one who, over a stretch of years, had personally seen and experienced the reality of life in America’s poorest communities,” writes Sullivan. (352) When he left the Justice Department to become a United States senator, he grew obsessed with the issue of poverty and its particular intersection with race. Perhaps because he was rich, he was stunned by the number of poor Americans that existed and by the extent of their poverty. Justice Rising does not look as deeply into the issues of American affluence, the preoccupation among liberals in the 1960s to end poverty, and the crisis of the American city as Edward R. Schmitt’s President of the Other America: Robert Kennedy and the Politics of Poverty, but its deep dive into the civil rights movement and its growing commitment to the Black poor and massively detailed account of Kennedy’s maturation in understanding race, racism, and Black Americans make it a nice complement to Schmitt even as it, as times, covers some of the same ground. Justice Rising is a richer narrative than President of the Other America. For instance, in the latter book, the fact that Kennedy graduated from the University of Virginia Law School is mentioned in one sentence. Sullivan begins her book with the story of how Kennedy, while a student at UV Law School, invited Ralph Bunche as a speaker in 1951. Bunche would not come unless he was guaranteed an integrated audience. Kennedy worked an arrangement with the dean of the law school to permit Blacks to attend and Bunche came. It tells something important about Kennedy, about his naivety and his determination.

Kennedy was, in the entirety of his career, certainly not all the things Jack Newfield called him in the epigraph that starts this section of my review. But he was close to it for many people when he died. It happened because of the era: velocity can compress change into a stunningly wrought distortion that captures and fulfills a moment. The 1960s were, as Justice Rising relates, and as I can remember from my boyhood, the best of times and the worst of times, bloody and bountiful. This made it a good time to be alive and Sullivan’s book gives us a Robert Kennedy who seemed very much alive and even grateful for how his times took his measure and made him grow. Sullivan’s book could have rightly been called The Education of Robert Kennedy, an account which richly educates us all.