Trial of the Century.

Given that label, one might assume that each century has but one courtroom drama worthy of that designation. But for the Twentieth Century, even the label Trial of the Decade would be inaccurate. That is because the one common denominator for each such Trial is that most memories and details have faded by the start of the next one. If you ask someone today to name the most sensational trial of the 1920s, they might recall the names, but no significant details, of Sacco and Vanzetti, or perhaps Leopold and Loeb, or maybe Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle. But when you told them that the most widely covered Trial of the Century that decade, both here and worldwide, was the Sash Weight Murder Trial of 1927, I would wager you would get a blank stare. (Go ahead. Google it.)

Nevertheless, for we baby boomers there is only one Trial of the Twentieth Century, broadcast into tens of millions of homes and offices from the opening statements in January of 1995 to the controversial “not guilty” verdicts ten months later. Yes, The People v. Orenthal James Simpson, in which the former football star (and “Detective Nordberg” in the Naked Gun comedies) was charged on two counts of murder for the gruesome multiple stabbings of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ron Goldman, whose bloody corpses were found on the front steps of her condo. For my generation, the name Kardashian evokes not the sisters of reality TV but their late father Robert, a member of that Dream Team. No, not the USA Olympic basketball team that included Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson. I refer to O.J.’s Dream Team of trial lawyers.

As with those who had lived through prior Trials of the Century, we boomers are startled to discover that if we ask our grandchildren to complete the phrase, “If it does not fit,” all we get is a blank store.

“You must acquit!” we say.

Still a blank stare.

“Johnnie Cochran!”

“Who?”

Sigh.

As expected with any Trial of the Century, the year or two following the jury verdict generated a stack of books about the trial, including insider tales by the two prosecutors (Without a Doubt by Marcia Clark’s and In Contempt by Christopher Darden ), three of the jurors (Madam Foreman: A Rush to Judgment by Armanda Cooley, Carrie Bess, and Marsha Rubin-Jackson), and two of O.J.’s Dream Team (Search for Justice by Robert Shapiro and Journey to Justice by Johnnie Cochran).

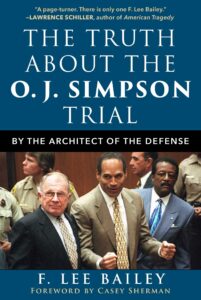

But pretty much silence in the publishing world by the second anniversary of the verdict. Until the summer of 2021, with the publication of what is likely the last in-the-room-where-it-happened memoirs. The author is the late F. Lee Bailey, a member of that Dream Team and once among the most famous criminal defense lawyers in America. He died just months before the publication of his book.

For my generation, the name Kardashian evokes not the sisters of reality TV but their late father Robert, a member of that Dream Team. No, not the USA Olympic basketball team that included Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson. I refer to O.J.’s Dream Team of trial lawyers.

Early on in the book, I was struck by that old adage about revenge being a dish best served cold—or here, best served dead. Although more than a quarter of a century has passed since the verdict, there is nothing tepid about Bailey’s festering contempt for co-counsel Robert Shapiro, which first surfaces in Chapter 1 and repeats throughout the book. In describing his initial call “from my then-friend Robert Shapiro,” who was seeking to enlist him in the case, Bailey writes that their conversation “was a harbinger of what trouble lay ahead—not only of what would become of our friendship and professional relationship, but also of his future ham-fisted handling in the Simpson case.” (4) And a few pages later: “[T]he biggest problem the defense had during the fifteen-month period that elapsed from arrest to verdict was not the evidence, or the defendant, but Robert Shapiro.” (8)

For those who had followed the case, this animosity is no revelation, since within days of the trial’s commencement in January of 1995, Shapiro had disclosed to the media that he and Bailey were no longer on speaking terms. Shapiro would eventually get his own form of revenge—served red-hot after the trial but never acknowledged in Bailey’s book. More on that later. I promise.

(Spoiler Alert: Bailey’s book is a somewhat eccentric, narcissistic, and incomplete recounting of the trial. For those unfamiliar with The People v. O.J. Simpson, a good source, including fascinating behind-the-scenes tales, can be found in The Run of His Life by Jeffrey Toobin and American Tragedy by James Willwerth and Lawrence Shiller.)

Early on in the book, I was struck by that old adage about revenge being a dish best served cold—or here, best served dead. Although more than a quarter of a century has passed since the verdict, there is nothing tepid about Bailey’s festering contempt for co-counsel Robert Shapiro, which first surfaces in Chapter 1 and repeats throughout the book.

In Bailey’s version of the trial—as the subtitle of his book declares—he was the master strategist and courtroom impresario while Shapiro was the bumbling and increasingly envious knucklehead who blew the preliminary hearing, believed O.J.’s best option was to seek a plea deal to manslaughter, and, when he learned that the jury had reached a verdict, made a panicked call to Alan Dershowitz to prepare the appeal. To his credit, Bailey does praise the performance of Johnnie Cochran, who became lead counsel, master strategist, and courtroom impresario, capping his performance with that powerful closing argument that included the “If it does not fit” mantra.

The heart of the book—and the heart of Bailey’s stated role on the Dream Team—is his attack on the credibility of the prosecution’s principal witness, Detective Mark Fuhrman. (104) By way of background, Nicole and Ron were murdered outside her Brentwood condo on the night of June 12, 1994. Fuhrman was one of the first detectives to arrive. He was familiar with O. J. and Nicole because of a domestic violence call he had handled a few years earlier. While the search continued at the condo, Fuhrman left the premises and, with three other detectives, headed over to Simpson’s residence—approximately an 8-minute drive. When no one answered the call at the security gate, Fuhrman climbed over the fence, opened the gate for the other detectives, and headed off on his own around the corner, where he claimed to have found a second bloody glove, which was later determined to be the right-hand mate of the glove found at the murder scene. DNA analysis proved that both gloves were soaked with the blood of the two victims.

Thus that second glove became one of the strongest pieces of incriminating evidence for the prosecution. Without it, the prosecution faced a daunting task, namely, the timeline of events. Kato Kalin, Simpson’s houseguest in the attached bungalow, testified that the two men had returned from dinner at 9:37 that night. The circumstantial evidence—especially the frantic barks of Nicole’s dog around 10:30 that night and Simpson’s emergence from his home at 10:55 pm with bags packed for his redeye flight to Chicago—suggest that if Simpson had really finished stabbing (multiple times) and killing both his ex-wife and Goldman by 10:30, he would have had just 25 minutes to dispose of the evidence, including the weapon(s) and his clothes, which would have been drenched in blood, then drive back to his house, take a shower to get rid of any residual blood, get dressed, and bring his travel bags out to the waiting limousine for the drive to LAX.

Under the prosecution’s mad-dash scenario, Simpson supposedly inadvertently dropped the bloody glove as he ran from his driveway through the backyard of his house to get cleaned up and pack his suitcase. Trying to imagine that sequence of key events in such a compressed timeline evokes a macabre version of the then-famous Hertz “Superstar in Rent-a-Cars” TV commercial featuring O.J. sprinting through the airport and leaping over barriers.

Bailey is assigned the task of preparing for and cross-examining Mark Fuhrman—an undertaking that unfolds over sixty-one pages (95-157) and whose theme is captured by the titles of Chapter 5 (“Planning ‘Furman’s Funeral’”) (95) and Chapter 6 (“Getting Furman in the Crosshairs”). This is the most interesting (although ultimately puzzling) portion of the book. As every experienced trial lawyer knows, the key to a successful cross-examination of a crucial witness has less to do with brains and oratorical skills than with a dogged commitment to the drudgery of endless research, document review, and witness interviews. That commitment began almost immediately upon Simpson’s arrest on June 17, 1994, which occurred after the most surreal event in that case—or any case—namely, the slow-motion chase along the Los Angeles freeways of Simpson’s white Ford Bronco, driven by his friend Al Cowlings while Simpson sat in the back seat sobbing and holding the barrel of a .357 magnum to his head, a battalion of police cars with flashing lights following behind, police and TV news helicopters hovering overhead—a sixty-mile pursuit watched by an estimated 95 million TV viewers.

The focus of the Fuhrman cross-examination research quickly became his long history of racism. The evidence uncovered was abundant and shocking. For example, Johnnie Cochran received a letter from one woman who had encountered Fuhrman on several occasions in the late 1980s. She worked in a real estate office in the same building as a Marine recruiting station and would occasionally stop by to say hello to the two Marines. During one of her many encounters with Fuhrman at that recruiting station, as she explained in her letter:

[He] said that when he sees a “Nigger” (as he called it) driving with a white woman, he would pull them over. I asked would [he] if he didn’t have a reason, and he said he would find one. I looked at the two Marines to see if they knew he was joking, but it became obvious to me that he was very serious. Officer Fuhrman went on to say that he would like nothing more than to see all “Niggers” gathered together and killed. He said something about burning them or bombing them. (115-6)

There was ample additional evidence of this racism from other witnesses. And though Judge Ito restricted the use of almost all of that evidence, F. Lee Bailey nevertheless strode into Court on the morning of the first day of cross-examination locked and loaded.

While Bailey’s account of his cross-examination is filled with self-praise for his brilliance, he nevertheless concedes that the media’s response was largely “meh”—a view the reader may share as well. But to his credit, Bailey did lay the groundwork for the later destruction of Fuhrman’s credibility by asking the following questions on the final day of his cross-examination:

Q. You say under oath that you have not addressed any black person as nigger or spoken about black people as niggers in the past 10 years, Detective Fuhrman?

A. That’s what I’m saying, sir.

Q. So anyone who comes to this court and quotes you as using that word in dealing with African Americans would be a liar; would they not, Detective Fuhrman?

A. Yes, they would.

Q. All of them?

A. All of them. (136)

And then, with what even Bailey concedes is a Hollywood twist, news broke of the scandalous Fuhrman tapes—thirteen hours of audio recordings over several years with a Hollywood screenwriter for whom he’d been acting as a consultant. As Bailey explains, “In these recordings, Fuhrman not only slung bitter racial insults (e.g., using the word nigger forty-one times) but he also talked approvingly of police brutality of black suspects and falsifying police reports to secure convictions.” (141) In other words, this was a defense lawyers version of manna from heaven—although Bailey is quick to credit the meticulous work of the investigator, Pat McKenna, who discovered that manna.

After those tapes surfaced, the final blow to Fuhrman occurred when he took the stand outside the jury’s presence. Although Bailey had set the stage days earlier with the q-and-a sequence quoted above, the coup de grâce was delivered by another Dream Team attorney, Gerald Uelman, who got Fuhrman to plead the Fifth Amendment to a series of increasingly damaging questions about his involvement in the case and his prior testimony, ending with Uelman asking, “Did you plant or manufacture any evidence in this case?” Fuhrman leaned over to whisper to his attorney and then sat up and answered, “I wish to assert my 5th Amendment privilege.” (156)

Bailey ends the book with some ruminations on the persistence of racism, the problems within the Los Angeles Police Department, and, of course, the unfair fate he was to suffer for years from what he labels “the damnation of an acquittal” in which “I was being viewed as a pariah by the white population for having wielded perverse skills to put a crazy murderer back into the general population.” (279)

But now, let us return to the real source of Bailey’s bitterness toward Shapiro, revealed in Chapter 8, appropriately titled THE “DREAM TEAM” BECOMES A NIGHTMARE. It is here where Bailey discovers that Shapiro’s contract with Simpson would pay Shapiro $1 million while Bailey would be a member of the Dream Team as a volunteer with no pay. Bailey is, understandably, outraged, and that outrage causes him to devise what he viewed as a brilliant revenge scheme, made possible by his involvement with the criminal defense of a wealthy drug-smuggling client of Shapiro’s named Claude Duboc. As Bailey explains:

Shapiro had apparently forgotten that I controlled the fees in the Duboc case, the substantial fees set aside for defense counsel by the government. So I could simply deduct what was ultimately determined to be my share of the Simpson case fee from Shapiro’s share of the Duboc fee.

In other words, we had each other by the short hairs.

Or so we thought. (81-82)

Bailey never returns to explain that final sentence.

And with good reason. To quote those Yiddish words of wisdom, “Mann Tracht, un Gott Lacht” (translation: “Man Plans, and God Laughs”) Bailey’s financial scheme exploded into a massive and ever-expanding scandal that began with his six-week imprisonment for contempt of court just a year after the O.J. verdict, followed by the Florida Supreme Court’s finding of guilt on seven counts of attorney misconduct, which led to his permanent disbarment as a lawyer. Finally, disgraced, he faced with a $5 million-plus debt to the Internal Revenue Service, a Chapter 7 bankruptcy filing in 2016. To paraphrase T.S. Eliot’s The Hollow Men, Bailey’s world ended not with a bang but a whimper.

While Bailey’s account of his cross-examination is filled with self-praise for his brilliance, he nevertheless concedes that the media’s response was largely “meh”—a view the reader may share as well. But to his credit, Bailey did lay the groundwork for the later destruction of Fuhrman’s credibility.

Moreover, his client’s victory lap was even shorter and led to far more toxic results. The families of the two murder victims filed a lawsuit against Simpson for wrongful death—a civil claim with a lower burden of proof than a criminal case. In 1997 the trial court entered a $33.5 million judgment against Simpson, who quickly moved to Florida to avoid paying that judgment. But then, in an even more absurd Man-Plans-God-Laughs plot, in 2007 he organized and led a group of men that broke into a room at the Palace Station hotel-casino in Las Vegas and, at gunpoint, seized a large collection of valuable sports memorabilia. He was arrested, charged with the felonies of armed robbery and kidnapping, found guilty, and sentenced to thirty-three years in prison, nine of which he served before being granted parole in 2017. He remains a pariah.

In short, the final chapter of F. Lee Bailey’s book ends with words that sadly resonate with the final chapters of his life and the post-trial chapters of his client’s life: “Shame, shame, shame!” (282)