Blaxploitation was born of crisis. Hollywood was in big trouble in the 1960s. The bloated studio system was dying under the weight of big-budget flops, shockingly out-of-touch products, and the rising popularity of television. On the brink of financial collapse, production companies were saved by an unprecedented boom in films that featured Black casts and targeted Black audiences. This massive cascade of pictures—roughly seventy between 1970–1975, starring slick-talking hustlers and Afro-sporting femme fatales intent on “sticking it to the man”—would come to be known as Blaxploitation film. While the term Blaxploitation was (and fifty years later still is!) a hazy genre designation mainly rooted in the critical discourses that surrounded the movies, people certainly knew a Blaxploitation film when they saw one. Indeed, these films were hard to miss! They dominated the box office and reshaped the possibilities and implications of Black cinema. Lucrative and controversial, they were hailed by some viewers as a revolution in images of Black empowerment and by others as pandering to longstanding racial stereotypes. Unapologetically Black characters fought back against embodied symbols of systemic oppression. They won. And like that, they were gone. Hollywood regained its footing with blockbusters like Star Wars (1977) and Jaws (1975), and the absorption and dilution of Blaxploitation-style cool into White bodies in films like Saturday Night Fever (1977) and Taxi Driver (1976). While dismissed by Hollywood as a handy trend, Blaxploitation has earned a shaky status in the history of film and Black cultural history at large. The propensity to elicit loaded for or against debates has led to equally overwrought praise and scorn for these films. A half-century after Blaxploitation’s bombastic introduction, quick rise, and equally quick fall, we would do well to revisit, and reconsider, those films that best exemplify the still prickly term. Below, in ascending order, are, in the parlance of their time, the five baddest Blaxploitation films:

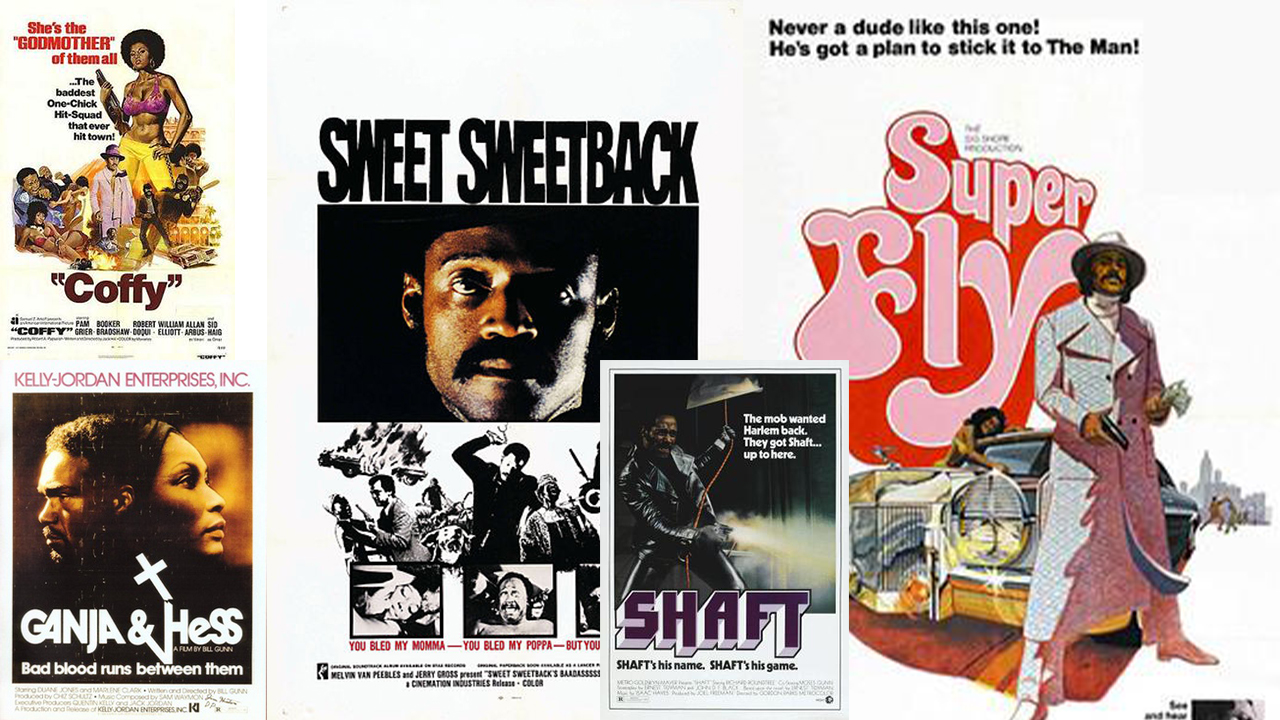

5. Coffy, directed by Jack Hill, American International Pictures, 1973

Pam Grier, the star of Coffy, holds the royal status of “Queen of Blaxploitation”—a precarious matronly rank to occupy in a phallocentric genre. At core, most Blaxploitation films are narratives of masculine revenge. And not simply revenge for a specific interpersonal slight, but a symbolic and cathartic vengeance for all Black men over the longstanding emasculating efforts of “the (White) man.” Understood as a pointedly interracial homosocial affair, Black justice was the province of those reacclimated men who confronted white male authority. Unsurprisingly, this masculinist tenor consistently resulted in flat or degraded female characters. Black women were generally present as evidence of male sexual vitality, violated objects who spurred counterattacks on White villains; or as untrustworthy bedfellows. Enter Coffy, the first action film to star an African American woman.1 As Coffy, Grier contends with the gendered landscape of Blaxploitation with a temptress’s wink. If most Blaxploitation masculine heroes repurposed racist myths of Black male hyperviolence and virility, Grier appropriated stereotypes of Black women as wanton Jezebels. Coffy usurps masculine authority by encouraging its brashness, using her sexuality to disarm men who assume their right to power over her body. This, too, is a revenge film.

After her younger sister falls victim to the drug trade, Coffy, a nurse, takes justice into her own hands. Barred from traditional sites and positions of authority, Coffy uses other means to get close enough to kill her power-wielding enemies. In the course of the story, Coffy disguises herself as a sex worker, drug addict, and naïve arm candy to kill a web of guilty parties, including pimps, drug dealers, and her corrupted politician boyfriend. The plague of drugs and corruption is depicted as an interracial homosocial cooperative, and Coffy lays waste to “the man,” Black and White alike. However, Coffy’s most impressive subversion of misogyny occurs in relation to the camera itself.

If most Blaxploitation masculine heroes repurposed racist myths of Black male hyperviolence and virility, Grier appropriated stereotypes of Black women as wanton Jezebels. Coffy usurps masculine authority by encouraging its brashness, using her sexuality to disarm men who assume their right to power over her body. This, too, is a revenge film.

Coffy’s director, Jack Hill, is no feminist. Hill had directed Grier twice previously in the crass “Women in Prison” films, The Big Doll House (1971), and Women in Cages (1971). His gaze is decidedly male. From the first shot of our protagonist, we view Coffy from the purview of a lusting drug dealer. She is half-clothed and half-conscious. She is (seemingly) a strung-out addict who would do anything for a fix. We see her as he sees her: strikingly beautiful and utterly desperate. In many scenes with Coffy, especially those that introduce her to a male character, sex is unabashed, while consent is, at best, tenuous. Her sexuality, like her power, is tethered to her endurance of gendered violence. In this respect, Hill draws upon the thematic backbone of another popular 1970s exploitation genre, “rape-revenge films.” Depictions of Coffy being violated double as the fulfillment of perverse voyeurism and as license to relish the justifiable catharsis of over-the-top retributive violence against men (Foxy Brown, Hill and Grier’s 1974 follow-up to Coffy, leans even further into this trope). As Coffy exacts justice, there is no room for sympathy for her victims because they are, at core, victimizers. Yet Coffy is not equally flattened; she is never simply a victim. Grier’s capacity to undermine the way she is framed is what makes her performance so gripping. Her violation, both by men in the film and by the male gaze of the camera, does not define her. The men only think it does. And it is exactly in those moments, when the gaze is most pornographic and Coffy appears most seductive or desperate, that her steamy look turns to stone, and she raises the shotgun she had been concealing all along.

4. Ganja and Hess, directed by Bill Gunn, Kelly-Jordan Enterprises, 1973

Ganja and Hess is not your prototypical Blaxploitation film. To begin with, it is a horror film, and most Blaxploitation films were realist urban crime thrillers. However, genre is not what makes Ganja and Hess unique. In fact, Ganja and Hess was greenlit after the success of Blacula, the highest-grossing horror film of the Blaxploitation cycle. The logics of racism and horror films have a great deal in common. Each is grounded in the projected embodiment of repressed, but always encroaching, fears. Fears that double as latent desires. In both cases, the things we will not face in ourselves take shape externally and come to confront us with terrifying results. Yet the average Blaxploitation horror film was, well, not particularly scary. Ganja and Hess is scary. Or rather, it is unnerving. Like a fever dream, the film’s hazy composition conjures not terror but a perpetual unsettledness. Not since Night of the Living Dead (1968) had a horror film so profoundly explored the meaning of race in America.

Dr. Hess Green, a very well-to-do anthropologist, is stabbed by his unstable assistant, George, with an antique African ceremonial dagger. In the wake of the stabbing, George thinking he killed Hess, kills himself. But Hess is not dead. Or at least, not the type of dead George had in mind. The dagger turns Hess into a vampire. When George’s widow, Ganja, comes to Hess’s home looking for her husband, the two instantly fall in love. Ganja soon becomes a vampire herself, and the two lovers wrestle with their immortal existence, their precarious bond, and their lust for blood. The results are as tragic and muddled as they are beautiful and genuine.

Like a fever dream, the film’s hazy composition conjures not terror, but a perpetual unsettledness. Not since Night of the Living Dead (1968) had a horror film so profoundly explored the meaning of race in America.

Reworking Bram Stoker’s classic tale, director and writer Bill Gunn (who also plays George) evokes Kubrick and Van Peebles to produce this uniquely moving vampire story. The average Blaxploitation film offered fantasy through realism. The streets, the language, and the music were all meant to reflect dimensions of Black life that had been historically unrepresented on screen. This realism made the fantastic catharsis of avenging a racist cop or politician all the more satisfying. Ganja and Hess provides no such stability. The surreal, nearly hallucinatory imagery and lyrical dialogue drive a narrative about the unrelenting precarity of African American identity, faith, and addiction. Themes of love and lust, need and want, home and homelessness, all sinuously chafe until they bleed into one another and produce the sustenance of the undead. From the outset of the film, title cards tell us in no uncertain terms that Hess is a “victim” and “addict.” In the eighty minutes that follow, we watch him kill and maim, fall in love, and exist in material splendor. Yet by the film’s end, there is no denying the utter truth of these designations.

3. Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song, directed by Melvin Van Peebles, Yeah Inc, 1971

Sweetback is an outlaw hero. Quiet, virile, violent when necessary and, at core, ethical, he embodies the classic qualities of cinematic masculine Americana. Yet never before had such qualities been embodied on screen by the likes of Sweetback. A homeless young boy sheltered in a brothel, he grows up to be a gifted sex worker. Palpably stoic, he sees the course of his life and the state of his political consciousness change forever when he intervenes to rescue a young Black Power activist from brutalization by two corrupt LAPD officers. After beating the two cops into comas, he runs from the law and the rest of the film follows him. The story is straightforward; it is just not told in a straightforward way. The action, including a sexual faceoff with a biker gang, an exploding car, and a knife fight against a police dog, is rendered as a series of vignettes woven together with psychedelic jump cuts and soundtracked by a then unknown band called Earth, Wind & Fire. Ultimately, with the aid of the community and his sexual superpowers, Sweetback escapes across the Mexican border. Not only does he get away, a feat no Black cop killer had accomplished on screen, but an epilogue flashes across the screen telling us that Sweetback would be back to “collect some dues!”

One of the striking things about Sweetback is that while it was unprecedented in the realm of cinema, the qualities of the film’s hero were far from new. Sweetback is an archetypical African American folk hero. A Black Power era Stagger Lee, Sweetback is what folklorists call a “bad man.” The ultimate signifying term, this “bad” man is, for one segment of society, bad in the sense of immoral or criminal while for another, he is bad in the sense of being justly and stylishly defiant. As folklorist and novelist Cecil Brown explains, “From the beginning this black man can never be the traditional hero because he has been cast in the light of the captive or the villain. As a result, he is forced to defend himself, but in doing so he will be seen as the anti-hero.”2 What makes Sweetback an anti-hero is that his lawlessness reveals the immoral nature of the White authority that criminalizes him.

The insurgent process of making the film has iconized Van Peebles himself as a creative folk hero. Van Peebles backed out of a three-film deal with Columbia Pictures (an exceptional contract for a Black director) when the studio refused to back the auteur’s vision for Sweetback. Across nineteen days of shooting, which were nearly as hectic as the film’s narrative, Van Peebles, who wrote, directed, and starred as Sweetback, completed his film independently (largely financed by Bill Cosby of all people). Getting his creative and provocative independent picture on screens was the next hurdle. Van Peebles showed a knack for promotion. Posters for the film stated that it was “Rated X by an all-white jury,” a nod to the racial implications of Hollywood power, point number nine of the Black Panther Party’s Program, and the film’s unapologetic embrace of Black aestheticism. While there is truth to the poster’s claim, it was also the inclusion of Melvin’s thirteen-year-old son Mario in the film’s opening sex scene that earned this rating. Nevertheless, the opening credits state that the film was “starring the Black community.” This was true in two important ways. First, Sweetback literally featured Black people on the street replying to questions about the whereabouts of the lam Sweetback. And, of course, none of them gave up his whereabouts. Secondly, the film focused on Black working-class people who had never been given screen time before—at least, not as featured characters, or characters doing anything other than serve White people. The film itself, in theme and aesthetic, was unquestionably revolutionary. Yet whether the message of the film was radical or regressive was the subject of a debate that would echo across the Blaxploitation era.

A Black Power era Stagger Lee, Sweetback is what folklorists call a “bad man.” The ultimate signifying term, this “bad” man is, for one segment of society, bad in the sense of immoral or criminal while for another, he is bad in the sense of being justly and stylishly defiant.

The film was divisive. Especially amongst Black critics. Huey Newton, the Minister of Information for the Black Panther Party, dubbed it the “first revolutionary film,” while eminent historian Lerone Bennet Jr lambasted the film stating, “No one ever fucked his way to freedom.” Whether it was revolutionary or pornographic—people, indeed, in the phraseology of the time “the people”—went to see it. Lines of ticket buyers snaked around blocks as theaters filled with cheering Black audiences. By the end of 1971, Sweetback, budgeted at $150,000, grossed in excess of $10 million. At that point, and for some time after, Sweetback was the most successful independent film in American history. Within the year, every studio in Hollywood, including Columbia, raced to replicate the phenomena. Less polished and more experimental than the majority of films it would inspire, Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song shifted the landscape of Black film for the next half-decade.

2. Shaft, directed by Gordon Parks, Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, 1971

A mononym has a unique power: cultural ubiquity of the highest order. Be it Prince or Beyoncé, the utterance of a single-named star reflexively compels a wave of associated meaning and influence. Shaft, the detective at the center of Gordon Parks’s 1971 breakout hit Shaft, embodies Blaxploitation in just such a way. Played by previously little-known Richard Roundtree, Shaft personified an assemblage of all the affective aesthetics of Blaxploitation. With his iconic theme song playing, this leather-clad and cooler-than-cool “black private dick” sliced through gritty NYC streets en route to avenge injustice or expertly seduce. The screen had never featured a hero quite like Shaft, who was refined, with a leading man stardom that Sweetback lacked.

Shaft was not intended to be palatable to White people, and that was what made him such a fresh hero.

Private eye John Shaft is hired by a Harlem gangster, Bumpy, to find his kidnapped daughter. In pursuit of the truth, Shaft navigates uptown drug-pushing hustlers and downtown law-and-order hustlers alike. He negotiates information and aid from both Black Nationalists and White police in the interest of cracking the case. At core, he is a loner whose only commitment is to justice. The story is a typical detective thriller. It was not the mystery, nor the motif of the reclusive suave detective, that made the film so distinct. Rather, it was the evocative stylization of the man and the political implications of his brand of justice.

His sexuality and violence worn with defiant pride, Shaft was all things Black film stars had never been allowed to be. In particular, Sidney Poitier, who had broken barriers with his box-office dominance during the previous decade. His “crossover” appeal made him the biggest Black movie star ever. Yet by the late 1960s, Poitier’s near saintly self-control in “race-problem pictures” like Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner (1967) was, for most Black audiences, painfully anachronistic. As the civil rights heyday languished under the defiant ethos of Black Power, Poitier’s characters read as politically compromised, always ultimately placating as they approached the edge of White palatability. Shaft was not intended to be palatable to White people, and that was what made him such a fresh hero.

As a photographer, Gordon Parks documented the civil rights movement. In his directorial debut, he offers a vision of a nation in the movement’s shaky aftermath, and gives us the one man capable of always retaining his balance. The opening five minutes of Shaft are a masterclass in establishing character and tone. A bird’s-eye view of NYC immediately establishes the size and bustle of our setting. Yet the camera quickly, seemingly instinctively, zooms in on Shaft emerging from the subway. Now at ground level, we move with Shaft as he traverses the crowded city. He brazenly steps in front of yellow cabs, smirks as he walks through a gathering of protesters, flashes his badge to urge petty hustlers to be more clandestine, and gets street info from a blind newspaper salesman. Surrounded by a hectic world, Shaft is in total control. Before the end of the opening credits, the tone of the entire genre is crystallized around its mononymous star, Shaft.

1. Superfly, directed by Gordon Parks Jr., Warner Bros, 1972

Superfly is Blaxploitation. The infamy of the film informs its unrivaled status in shaping the genre. In the strictest of semiotic terms, there was no Blaxploitation before the frenzied response to Superfly. In 1972, when Junius Griffin, president of the Beverly Hills chapter of the NAACP, introduced the term “Blaxploitation,” he meant it to be no compliment. It was a pejorative label and referred especially to Gordon Parks Jr.’s inaugural film. Superfly was, Griffin insisted, “gnawing at the moral fiber of our (Black) community.”3 That this appraisal was overwrought should not suggest that he was wrong to have concerns about the weight of the movie’s influence. The highest-grossing Blaxploitation film ever, with an initial box office of $24.8 million, Superfly was a sensation. It was especially popular among impressionable youth. There is no doubt that the film, with its drug-pushing protagonist, Youngblood Priest, was cool. It was what made him cool that drew some ire. The film redefined Black cool as rooted in a disaffected individualism that bordered on the nihilistic.

This seemingly prototypical antihero gangster story of Priest, a successful mid-level drug dealer angling for one last big score before getting out of the game for good, is a landmark on the shifting terrain of Black popular iconography. Superfly signaled the passing of the civil rights era’s righteous hope and the birth of a distinct conception of post-Black Power self-determination. This self-determination was heavy on the self and premised on securing the good life, not contributing to the collective social good. Priest embodied some of the most troubling questions about the true impact of the racial progress of the previous two decades. Where had all that hope gone? And what was replacing it?

Even his name, Youngblood Priest, signified a chuckle about the upstart pusher-man replacing the passé holy man as a source of comfort. His tasteless, yet clever name captures the nature of his self-awareness. Priest is not in a state of Sweetback-esque preconsciousness. He is, from the opening scene, the most self-aware character that the genre ever produced. It is Priest’s self-awareness and fierce self-determination that make him both seductive and insidious. He is not apolitical. Rather, he chooses the “wrong politics,” knowingly discarding Black Nationalism as a floundering enterprise. Nor is he stoic in his masculinity. In the shadow of the macho fortitude of Sweetback and Shaft, Priest speaks deliberately about his ambitions and vulnerabilities. Perhaps he is amoral, but he is thoughtful. His amorality is a consequence of a disaffected logic. Despite his unapologetic approach to his corrupted occupation, it is hard to hate Priest. And it is this battle of our political will to hold onto the ethics of the civil rights age, versus the sway of Priest’s calculated seductiveness, that makes him so singular. A decade before Tony Montana in Scarface (1983), through Priest, audiences rooted for the bad guy and wondered: is he really so bad? If only he had different opportunities, or if only he had the right person in his life, would he be different? In other words, he hustles us. And perhaps, the film gestures, hustling was the only option left to him.

Youngblood Priest embodied some of the most troubling questions about the true impact of the racial progress of the previous two decades. Where had all that hope gone? And what was replacing it?

Curtis Mayfield’s iconic soundtrack is the perfect soundscape for the hustler and hustled alike. Mayfield’s falsetto floats atop dank basslines, whispering like a devil on the shoulder of a desperate man considering the fate of his last five dollars. Sonically, visually, and thematically, Superfly is characterized by a mixture of grittiness and flashiness. Priest traverses gray alleys in pastel overcoats, striding upright past slumped bystanders and spending big bucks in shoddy establishments, all while leisurely imbibing the substance he pushes to despairing addicts. The insistence on such incongruences makes our hero’s decadence all the more pronounced and haunting. It is a city in decline and an anti-hero on the rise. And these two phenomena are not unconnected. His high life is purchased by the city’s slow death. Yet Priest is not happy. His life is shiny but hollow. He manages his palpable spiritual malaise with such disaffected grace that one can confuse his composure for fulfillment. It is his disaffectedness, not his money or his trade, that is the heartbeat of his supposed glamour. Superfly is a film about the type of aspirations that are bred by hopelessness. And there is no tragedy like hopelessness. Except maybe, the embrace of hopelessness as glamorous.