He thumbs through somebody’s cast-off biology textbook, curious whether, at fourteen, he can figure it out. In the student union trash can, he finds some chicken salad; a few hours later, he throws it up. There is no good place to rest; February has frozen all forgiveness from the ground. Finally, he feels a blast of warm air from a giant heat vent behind a bike rack in the lobby of one of the Washington University dorms. He waits until dark and crawls back there, dragging a torn quilt he also pulled from the trash. Through the wheel spokes, he can see students pushing through the residence hall doors—boys in navy pea coats and caps, girls in mini-skirts with macrame bags slung over their shoulders. He steals hope from the kids in tie-dyed tunics and bell-bottoms, imagining a group of mellow, freethinking hippies taking him in, making him their mascot. They bring him to their classes, and when the professors fire questions, he knows the answers. They raise an eyebrow, pleased, and let him stay. . . .

A loud voice breaks the fantasy. Shoving a slush-covered bike against the full rack, some wiseass is cracking jokes to impress his girlfriend. From his dark nest, Gary reaches to steady a bike as it careens toward him, then holds his breath until the couple is gone. Other students approach, laughing, clutching books meant to win them bright futures. He makes up stories about their homes—aproned moms and kindly fathers, meals full of laughter. From a pair of glossy boots hurrying past the bike rack, he invents a tender and tempestuous romance. “I knew I loved you the minute you . . . ” Wrapped in possibility, he dozes off.

“Hey, what are you doing? You can’t sleep here!” The sun is up, and a security guard is peering into the shadows behind the bike rack. Half awake, Gary stumbles to his feet, apologizes, grabs up the quilt and his bag. “Get lost!” the guard yells after him, though he already is. Passing students avert their eyes, no doubt thinking it more polite.

All the vulnerability that made his childhood miserable—the sensitivity his father used against him, the softness other boys savaged on the playground—hardens in that moment. He has to be cooler, tougher. He has to stop feeling.

He hates them. Hates himself for dreaming of a soft landing with the flower people. Who wants to be their fucking mascot, sit in their safe little world while they talk about their old man and what a drag that he wants them to go to law school? Gary walks to Forest Park, where he meets a rough handful of crystal junkies and acidheads and gloms on to them instead.

When the police raid, he ends up in juvenile detention. The next morning, still too high to eat, he is staring at a piece of white bread when the news comes through a radio speaker: “. . . including a fourteen-year-old, in a drug raid near Forest Park.” Hey, that’s me, he thinks, hot with a rush of fame. A few seconds later, the real point clicks: His life is over. He is a criminal. He is in jail. All the vulnerability that made his childhood miserable—the sensitivity his father used against him, the softness other boys savaged on the playground—hardens in that moment. He has to be cooler, tougher. He has to stop feeling.

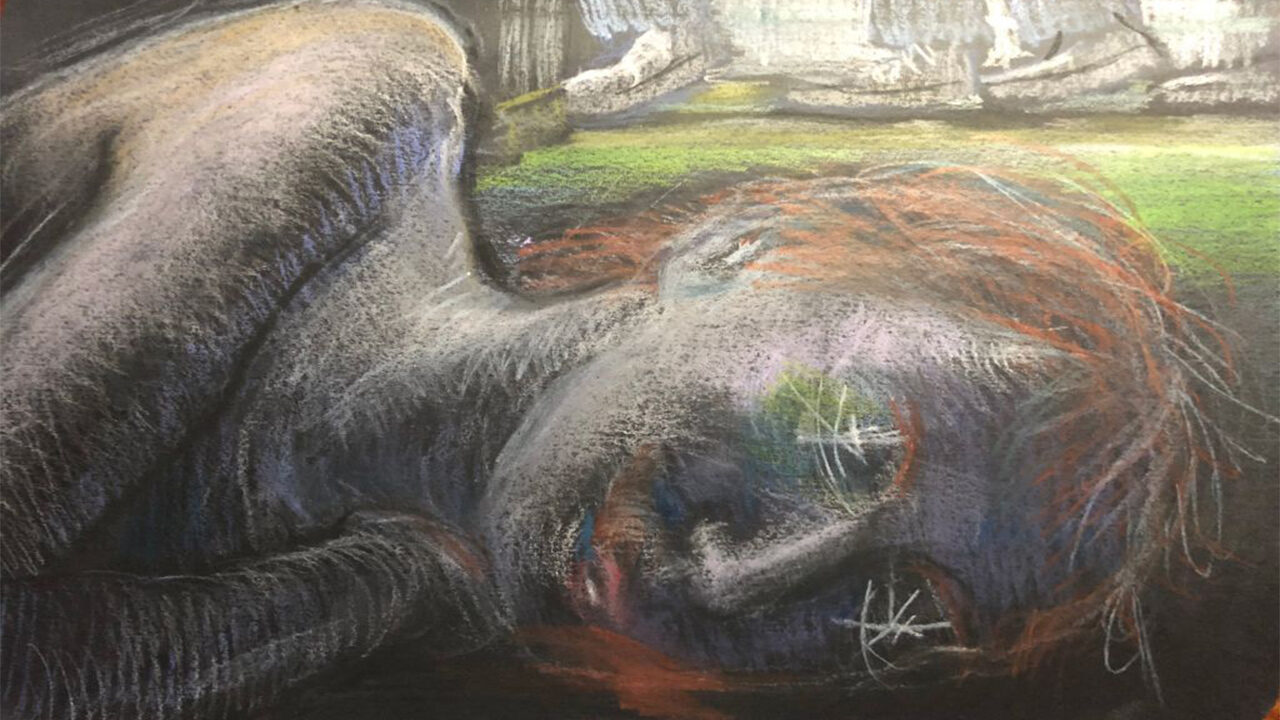

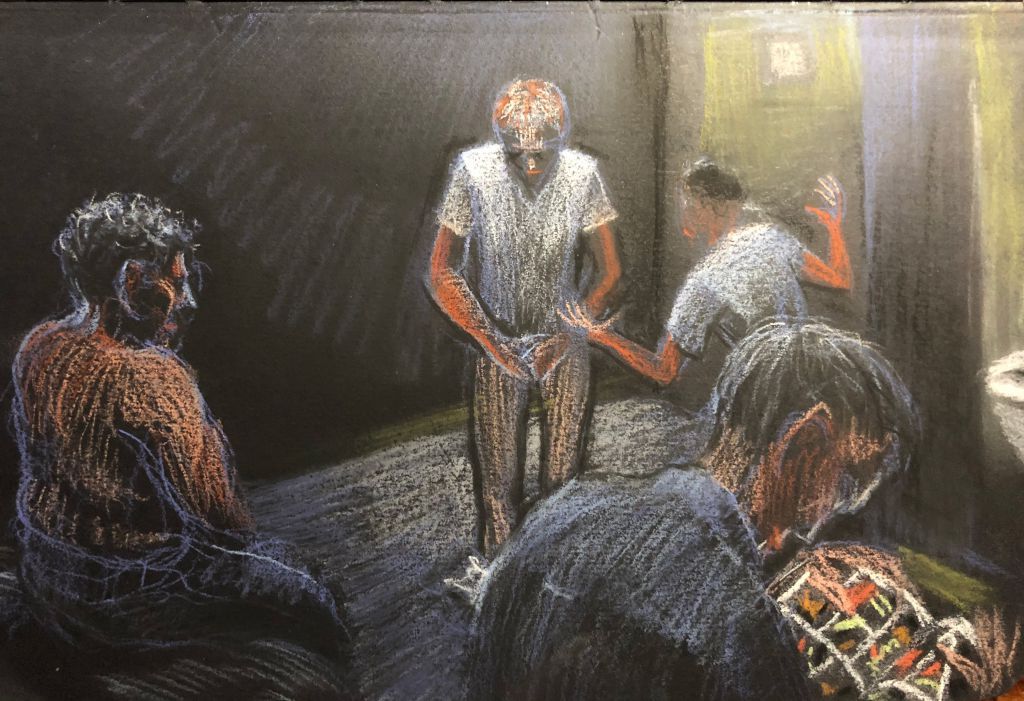

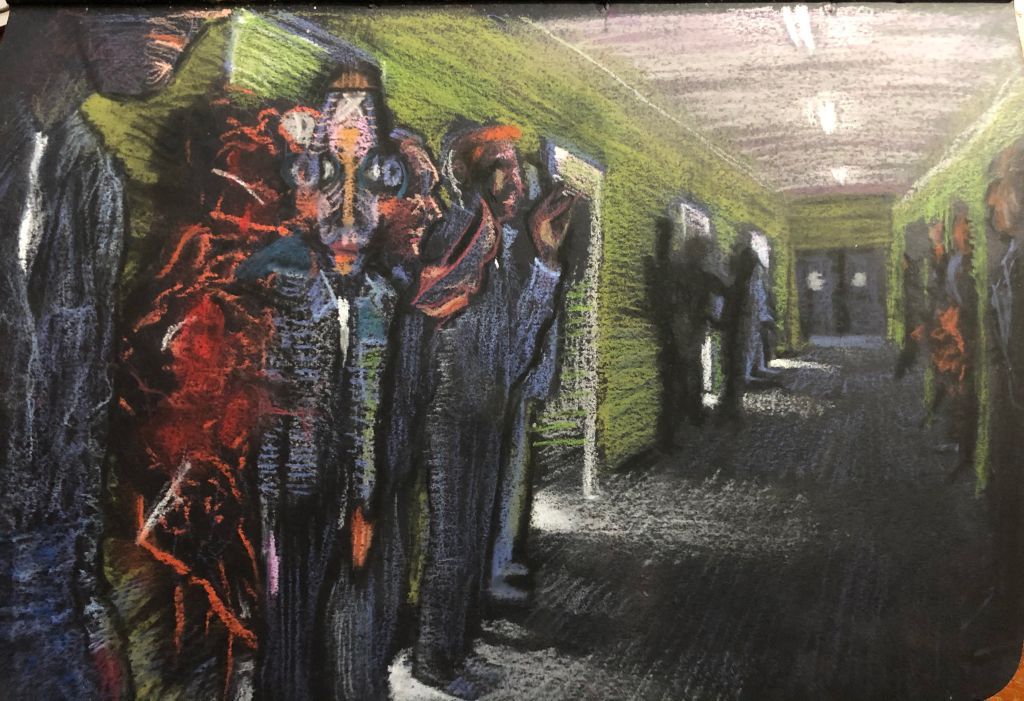

Art by, and courtesy of, Gary Bankston.

He is placed with three other boys—their territory a cell so big, parts of it cannot be seen through the window in the door. By that time, he has gone so numb that it takes him three days to tell a guard what they are doing to him. The guard looks disgusted—with him, too. Fine, he says, Gary will be moved that night after dinner. He is not. Nor is he moved the next day. All told, he will realize when he counts back through the blur, those boys raped him on and off for five days, using fists, body parts, and a rolled-up National Geographic.

• • •

By the time I receive an email from Gary Bankston (a pseudonym), all this is ancient history. He has been—at least on the surface—every bit as lucky as those Wash. U. undergrads he envied. He, too, graduated from college, and soon he was doing illustrations for the New Yorker and winning and judging CLIO awards. He found a groove as a technologist and project manager; designed a website for Yale University’s Climate Institute and launched one for IBM’s credit union; had poetry and essays published in Salon and various anthologies; wrote a play that was produced off-Broadway; raised three daughters and cared for the eldest during her long, painful death from cancer.

But once she was gone and his other daughters were on their own, his past reached up from its deep grave and took hold of him.

A therapist suggested ketamine and shock therapy, and he was tempted. But it felt wrong to erase what happened. By now, he knew that most kids who endure some form of abuse, either in home or in the system, are not White and male, thus have even less power than he had. They are silenced by default. So instead of wiping away the memories, he started contacting lawyers, judges, social workers, reporters.

Rape still happens behind bars, he pointed out, though nobody wants to talk about it. Runaways who deal drugs to stay alive still wind up housed with kids far more brutal. And there are still more than 10,000 kids under eighteen in adult facilities on any given day—how could you justify ten, much less 10,000?

The facility where Bankston was raped was a feeder for the infamous Boonville reformatory, a place that gave me shudders when I wrote about its sordid history twenty years ago. City truants and runaways in their early teens wound up in rural Missouri, beaten by redneck guards, put in solitary, sodomized, transferred on a whim to even harsher adult prisons. The place is legend.

Runaways who deal drugs to stay alive still wind up housed with kids far more brutal. And there are still more than 10,000 kids under eighteen in adult facilities on any given day—how could you justify ten, much less 10,000?

“What has never been reported,” Bankston writes, “is that the urban juvenile facilities that fed Boonville were just as bad.”

He is contacting me at the suggestion of Tom Albus, first assistant attorney general for Missouri. “I read with sorrow your note . . . I am afraid there is nothing that can be done for you under the law given the age of the misconduct against you,” Albus wrote, then supplied a link to that old Boonville story before concluding, “I am sorry for everything you went through.”

No one had ever responded so kindly. The replies were usually brief and perfunctory, and rather than sound shocked or try to contradict him, simply said, “I’m sorry you were there at that time.” Those were years when Missouri assigned no lawyers to juveniles and offered scant protection for “kids written off by their parents or pronounced ‘incorrigible’ with that abominable catchall law that made it possible for you to lose your life if you stole a pickle,” as Bankston puts it.

When he looked me up, he found me working at Washington University, the last place he ran to before his life fell completely apart. “That we are connecting now, given your association there and the yearning and envy I felt at fourteen, hiding among those students, is poignant to me,” he writes.

It is poignant to me, too. All those students wrapped up in their own safe world just as I would have been, feeling brave because they marched with King or smoked some reefer, oblivious to the boy envying them from the shadows. . . . But Bankston’s email sinks me into my chair like a weighted blanket. I have no desire to dredge up bleak, depressing Boonville or anything like it. I want to write about current issues—Boogaloo Bois, toxic masculinity in the political sphere, the bullies who are threatening democracy. Besides, readers are exhausted right now, worn down by a pandemic and a contentious election. They do not need a stranger’s old, unresolved pain. Nobody is going to do anything about what he went through, and what could they do, half a century later? What is the point of writing about this?

This is the dark secret of nonfiction: the way it tries to suck themes out of other people’s lives, even when their suffering was pointless and undeserved. Instead of trying, I decide to send a polite reply. Sorry for your loss, as we tell people who grieve.

But I keep seeing this kid crouched behind the bike rack, his jeans frozen hard and slicked with ice where he doused them with water to scrub at the urine stains.

Somebody else’s pain can make a claim on you.

• • •

Before Gary got arrested, his new friends sent him out to beg for drug money. An old woman fished him out a ten and urged him to go home. Thoughts zipping around like fireflies, he talked fast, mixing truth and fiction, and sobs broke through the speed’s hard acceleration, and he heard himself admit, “I can’t go back.”

At eleven, he had fallen in love with a boy. He had been trying to run away ever since, sure that any day, his father would figure it out and explode. The other kid had just wanted to experiment, but Gary had been engulfed by a worshipful tenderness. He cannot forget those feelings, and his father will never forgive them.

And so he lands in juvenile detention, where lessons his father has already taught him—hope is useless; just endure it; no flinching; no tears—prove helpful. Also, he is funny, and makes the other boys laugh. They find out he can draw and have him do Bic pen tattoos on their arms.

Stomach roiling, Gary keeps his head down so Leader knows he can hit him if he wants. Magical thinking comes easily: If I say or do just the right thing, he will stop.

The three boys in the big cell seem at home, like they have been there forever. He privately names the tallest “Leader” and figures him for seventeen. He is maybe five-eight, a bully and a sadist. John is younger and shorter, stocky, cognitively delayed. The third boy, whom Gary thinks of as Shrimpy, is about thirteen, five-two, slight, a nervous talker.

As the bullying starts, Gary thinks, “Oh, okay, Dad shit.” Used to sadistic punishments, he bends to pick up his pants, which they demanded he remove. Leader slaps his hand, knocks the pants back to the floor. “Go get ’em,” Leader says, then kicks at him and misses. “Fuck. You little faggot fuck.”

Stomach roiling, Gary keeps his head down so Leader knows he can hit him if he wants. Magical thinking comes easily: If I say or do just the right thing, he will stop.

Later, he will wonder if these five days would have been easier or harder if his dad had not trained him.

• • •

After Gary is finally moved, a boy who looks about nine years old is put in the large cell. He seems sturdy enough, just an ordinary kid. But that night, Gary hears him scream from down the hall and knows exactly what is happening. Nausea fights with a twisted relief—at least he is out of there—and guilt.

The boy comes out of that cell broken, shaking and crying, unable to move forward unless he is pulled along.

Gary does not approach him. From here on, he will wish he had tried to save him. Years later, he will say, over and over, “He was just a child.”

His therapist will suggest he look at a photo of himself at fourteen.

• • •

What is it, I ask Bankston, that makes kids take on responsibility for other people’s sins?

“I think it starts with tv and movies, and how boys are told men should behave,” he says. “We hold up as shining ideals those who stand up to injustice, who lay down their lives, even, to defend principles. I was bigger and older than that boy. I could have caused a fight, a scene. If I had slugged Leader in public, accused them in a loud, self-destructive way, that younger boy would have been removed from that cell at least. So, yes, I understand that it wasn’t my fault—but every excuse is mooted by the look on that boy’s face, his rubbing his arms compulsively. In the real world, some things require risking all. At the age of fourteen, I faced that adult choice, and I failed.”

I am so tempted to delete that paragraph, erase this useless guilt. But it has informed his entire life.

• • •

When Gary comes home from juvie, his brother notices a difference. Gary volunteers just a bit of what happened, not even the worst. Dead silence. Two weeks later, his brother brings it up, stammers, “You weren’t really…hurt, right?” He is giving Gary a rock album, and the present feels like a trade for comfortable silence. “Okay,” Gary says, feeling something shut down inside. “If that’s the way you want it.”

“So we’re okay, right?” his brother asks. “We’re okay? Okay.”

Later, Gary tries to tell his two best male friends what had happened. They both edge up to the same question: “Why didn’t you fight back?”

Gary lets the friendships drift, practices being friendly and blank and stoic. He marries young, a woman he trusts and can laugh with. Her sexuality is as confused as his, but their bed becomes what one of his favorite writers, Kurt Vonnegut, called “the country of two.” They move out West, get pregnant. The marriage shatters. Fast developing late-onset schizophrenia, his ex-wife shows up one evening and hands over their baby.

He is no longer happy, funny, necessary Dad; the girls are all grown up, strong and independent. And now that his life has no purpose driving him forward, he needs to go back.

He raises Molly as a single father, moving from Missoula to Greenwich Village. When she is nine, he meets a sweet, funny, easygoing woman named Barb (also a pseudonym) at the Graphic Artists Guild. “Your portfolio is full of bison!” she teases. One day she walks him to the elevator, and somebody asks if she is nervous about that evening’s board meeting, when she will find out whether her contract has been renewed. “God, yes,” she says, leaning her forehead against Bankston’s chest for a second. Electricity shoots through his veins. When he leaves the building, he finds the first payphone and asks her out.

They marry and have two daughters. When the girls reach their teens and began reminiscing about funny family stories, Bankston tries to tell a few funny stories from his own childhood—and sees stricken expressions on the faces of his wife and daughters. Most of his funny stories end with “a bare-assed belting.”

As he watches his girls reach adulthood free and easy, well-loved, a thorny jealousy begins to grow, twining around his chest and limbs, immobilizing him. Appalled, he cuts free of it, but he emerges gasping. He is no longer happy, funny, necessary Dad; the girls are all grown up, strong and independent. And now that his life has no purpose driving him forward, he needs to go back.

• • •

“You hold trauma until you come to terms with it,” Bankston has realized. “The body doesn’t let it go.”

In his case, this was literally true: His anus was pushed sideways by thickened scar tissue, and he needed reconstructive surgery. Emotionally, he was frozen into geniality for decades. Now, when his therapist pushes for some authentic emotion, he feels only terror.

Then, when the ice finally melts, there is lava underneath. He bubbles over, making wildly inappropriate disclosures at wildly inappropriate times until he finds a new equilibrium.

Art courtesy of Gary Bankston.

On Zoom, he holds up the book that helped: The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk, M.D. “All day long, I’m never more than five feet away from this book,” he says quietly.

I check it out from the library, learn about the layers of complex trauma, when later assaults pile on top of a precarious childhood. Sometimes people dress up their trauma like a voodoo doll, adding eyes and a mouth, letting it become them. Bankston is wary of that: “One can become sort of mesmerized,” he remarks. “There’s this weird—I don’t want to say ‘romantic’ but it’s like that—attachment to one’s pain.”

To avoid that mire, he seeks out people who suffered something similar. On a thread about Boonville in a prison forum, he writes what happened to him and finds other men who went through the same thing. He also volunteers for 1in6, a nonprofit founded “in response to a lack of resources addressing the impact of negative childhood sexual experiences on the lives of adult men.”

Emotionally, he was frozen into geniality for decades. Now, when his therapist pushes for some authentic emotion, he feels only terror.

Bankston introduces me to one of its cofounders, Dr. David Lisak, a clinical psychologist who survived sexual assault himself.

“People have a sort of simplified view of trauma and its aftermath: You’re hurt and then you heal,” Lisak tells me. “The way we use the word ‘resilient,’ it has a connotation that somebody bounces back, like we are made of rubber and trauma pushes us in various ways and we bounce back to our former self. For severe complex trauma, that is not the case.” He is heartily sick of well-intended, simplistic assumptions: “You should be over this by now.” “It’s time to move on.” “You need to get on with your life.” “Most Americans have no idea what some of our children go through,” he says. “This level of trauma changes you.”

It shapes the rest of your life, and it leaves you wondering who you might have been without it.

“At the age of sixty-four, I finally admit to, talk about, what happened,” Bankston says. “This has both improved and devastated me.” We all come to terms with the ways others judge our lives, he says, “but what if judgment of us was the thing, and it was accompanied by humiliation, violence, a complete lack of dignity? Logically, now, I understand that it was just bad luck that those boys ran their projections—faggot—on a boy with a confused sexuality and at a time when they had the whole culture on their side.” Nonetheless, he absorbed their loathing and set it alongside his father’s.

• • •

A varsity tennis player, Gary’s father got his girlfriend pregnant, married her, and regretted it. What he longed to be was an astronaut—and was about to apply anyway, family be damned, when he contracted polio. Now he had to lean hard, literally, on the kids and wife who were constant annoyances to him—Gary especially, because he seemed to be retarded, unable to speak until age five.

He did speak, though, whenever he was alone with his grandmother. She gave real love. His father dangled kind words and then snatched them back. Any frustration—if the popcorn spilled or the kids talked too loud and he could not hear Bonanza—could spark rage and a beating. As training for healthy nutrition, he shoved Gary, age nine, into a baby chair and force-fed him Brussels sprouts until he vomited.

Gary’s mother sometimes seemed like she was on the kids’ side, sometimes not. And then one day she was gone, committed to a mental hospital. “She exhausted herself with diet pills,” Gary’s father told them.

Gary and his brother and sister reminded one another that “life with Mom was crazy,” talking about how she used to shake out and re-re-re-count her pills; pour cigarette butts from one ashtray into another; walk their dog, Faux-Pas, up and down the stairs, saying, “He’s getting exercise, see?”

There were times Gary was afraid his father would not be able to stop, would just keep going until he killed him.

But with her gone, Gary had to try even harder, at school, to pretend his life was normal. He had already figured out how to walk with John Wayne’s side-to-side swagger. To talk football, he only needed to learn about ten expressions. When he was alone with himself, though, he still was not sure who he was. He had melting, tender feelings for some older boys, but he also felt a shiver of arousal sneaking glances at the women in his dad’s magazines. There was the thrill of transgression, the spiral of finding his own arousal arousing, the envy he felt for those lace-clad women that men hungered for—to have them, to be them, to be wanted.

What would his father do to him if he was gay? He remembered, could not forget, the day his sister came bouncing into the room and their father punched her, nearly broke her jaw. That had been unusual even for him; usually, there was a buildup. They all knew never to show expression, because crying enraged him. There were times Gary was afraid his father would not be able to stop, would just keep going until he killed him.

And so, at eleven, Gary started running away. He got farther each time—once to western Kansas, once across Nebraska. February 1970 was his last try, and he never even made it out of town.

• • •

You never know what will help. Bankston’s final breakthrough comes when he is (mis)diagnosed with classical Parkinson’s and prescribed high doses of several drugs, including Selegiline, which contains methamphetamine. Those interior walls he built so carefully? They all collapse at once. Up all night, he posts compulsively on Facebook, pouring out a lifetime of pain. In the morning, Barb reads what he has posted.

She knew about Gary’s father but not about the rapes, and definitely not that her husband was bisexual. The ground beneath her shudders and cracks open.

“It’s hard to learn after so many years that someone you love has been through so much trauma,” she says, then takes a breath and finishes in a rush: “and also to just learn, after twenty-some-odd years of marriage, that your husband is bisexual.” She gives a rueful little laugh. “It’s just a lot to take in.”

The daughter of Holocaust survivors, she was used to absorbing the suffering of people she loves. She knows how to give solace, how to give space. But this? “What does this say about me?” she cannot help wondering. “How could I live with him all that time and not know this? And how do we define a relationship that’s been based on secrets?”

Relatives urge her to leave him. There are days she wants to. Then it sinks in that he was trying to keep those secrets from himself as well as from her. They agree to give the marriage a year. Then another.

Bankston, meanwhile, joins a gay men’s group and sees that “they’re all mixed bags.” He might be gay, but he might not be entirely gay. What he lost years ago was mainly the chance to figure it out; to be himself, exuberant and free of shame, like the young gay men he sees these days.

Desire, though, was not love. Desire was fickle, a game or a chemistry experiment. The fact that he can desire men and women while Barb feels desire only for men—what does it matter, as long as they land in the same place, still wanting to share a life?

“It turns out that love is precious no matter where you find it,” Bankston says. “Very few women would put up with the revelations of my life in the past few years. But I can’t say I was denied love, because I wasn’t. Nor was I denied the opportunity to rise to the expectations of that love. I have lots of regrets, more than are realistic even, but I don’t regret for one moment meeting and embracing Barbara.”

• • •

Setting out to chronicle his life, Bankston writes, “If you have never been harmed, violent, sustained harm, or deep, early betrayal—you might struggle to understand how easy it is to internalize shame.”

He is right. It took me years to understand how a man can break down his wife’s self-esteem, terrorize her to the point that not only does she stay, but she defends him. Or how a little girl grows up sure that somehow it was her fault she was abused.

We talk far less often about men who are paralyzed by trauma.

“There’s so much about traditional masculinity that is really, really unhelpful,” Lisak sighs. Unmanaged, aggressive energy explodes into small cruelties that then become group norms. I think of Bankston’s father, and how a small boy’s temper can drive a grown man’s rage.

Ronald Levant, who specializes in men’s psychology, observes that many men wind up with a mild case of alexithymia: the inability to name their emotions.

The biggest relief of the gay men’s group was being able “to practice not being afraid of men,” Bankston says. “Most men are not a physical threat to me, I know that, but I also know they are capable of a very rapid response. If you’re paying attention, you can see the eyes go dead, the hands change. Men can feel completely justified and go too far, because they are modeling Dirty Harry.”

That mustered toughness feeds on silence. Ronald Levant, who specializes in men’s psychology, observes that many men wind up with a mild case of alexithymia: the inability to name their emotions. “You can’t show weakness or vulnerability,” Lisak agrees. “Obviously, you can’t cry. You can’t ask for help. And the strictest rule of all: You can’t be feminine. What’s the worst thing a man can call another man? A pussy.”

The worst things women call each other are all female words. I am not sure what this tells us. Weakness is equated with the female, that is an old and ludicrous fact. Yet it feels worse to me to be told you have not measured up to your own body.

• • •

It turns out this is a story about toxic masculinity. I ask Bankston—who has borne its scars and faked its attributes—what causes it.

“The essential thing, you mean?” He leans back. “It’s not that men are violent, or arrogant know-it-alls. Those are manifestations. The essential problem of masculinity is self-righteousness.” Fueled by testosterone and cultural pressure, such a man claps on bits of self-justification like armor, then bullies his children, spouse, subordinates, protesters, whoever is in the way of how he wants to see himself.

Women can fall prey to this rigid self-righteousness too, he adds. One dead giveaway is the absence of humor. “Have you noticed that Donald Trump never, ever laughs? He is the poster boy for toxic surety. Whenever I feel self-righteous and certain, I throw a big red flag up, hesitate, and let everything wash through me.”

He was not always so restrained. Early on, there was a barroom fight in which he went limp, letting the guy think he was just going to take it—the way he had with his father, the way he had in prison—then pulled his arm back and sank it into the guy’s solar plexus, stealing his breath, thinking as he hit the floor, “That’s one.” “Pretending to be a regular John Wayne made me that guy,” he says, “and for a while it felt buoyant.”

“It’s not so much drum circles as that we admire the wrong things,” he says wearily. “We need the experiences that grow out of our lives as lived, not as compared to the American ideal.”

The next time we talk, he blurts, “Men can never just be. We are not comfortable simply existing in the world. The incessant need to contain and control is almost the only message we get. Women inhabit a space that intersects with whatever is happening now. Men are forever operating like the captains of a ship, always in a greater world, going to a greater place.”

The antidote to toxic masculinity, he has decided, “is not containment and control, but release.” I mention the men’s movement a few decades ago, the healing rituals so easily mocked. “It’s not so much drum circles as that we admire the wrong things,” he says wearily. “We need the experiences that grow out of our lives as lived, not as compared to the American ideal.”

Art courtesy of Gary Bankston.

His face changes, lights. “It occurs to me,” he says, “that this has to do with play. Small children make mudpies, and there is the play of adults, which America is very good at. But we are terrible at the step in between, the play of developing adults. We allow them to drink and vomit and turn their nether regions into petri dishes on live tv.” He talks about a French village in the Vaucluse where young people are turned loose to run as wild as they like (harmlessly, through the surrounding fields and forest) for a year, and how those too rigid to play and let loose are never trusted. In this country, the ways young men ritualize their negative behaviors include sports and crime and warlike aggression, but nowhere near enough absurdity. He is delighted by the game Floor is Lava, because nobody can lord it over anyone else; it is all too silly, like those Moose Club headdresses and secret rites in the Fifties. Today, men’s world is mainly grim.

His grin fades. “That toxic rigid mindset—that’s what happened in that jail. The staff and the system that supported them were conspiring to allow some of the men to have free rein, and the assumption was that even if it was not legally right, it was right. ‘They deserve it. They’re animals.’”

• • •

“Why didn’t you fight back?”

In The Body Keeps the Score, Van der Kolk describes an experiment in which “dogs who had earlier been subjected to inescapable shock made no attempt to flee, even when the door was wide open—they just lay there, whimpering and defecating.” When someone suffers helplessly, their brain rewires in self-defense. They secrete more stress hormones, triggered even by mild everyday frustrations, and they stay vigilant, seeing danger everywhere. “The great challenge is to find ways to reset their physiology,” van der Kolk writes, “so that their survival mechanisms stop working against them.”

That was finally beginning to happen for Bankston, after decades wondering which tree was going to fall on him, how soon the bus behind him would careen onto the curb. “I don’t usually get normal depression,” he remarks. “It’s almost like I’ve got so much shit going on in here that I can’t settle into malaise. How can you be depressed when you have to be on guard about the bus going up on the curb?”

A few years ago, though, he reached a place where at least those thoughts did not stab him with panic. He had finally learned how to stop living in dread.

Then a pandemic broke out.

His laugh is wry. “It’s like I’m in a round-bottomed boat, and I’m finally staying afloat, and now the universe says, ‘We changed our mind. Dread.’”

• • •

I have to ask: Does he want revenge?

“I’ve spent too many hours of my life having 3 a.m. rage fantasies,” he says. “I’ve exhausted myself. I would not be the half-assed Buddhist I hope to be if I sought vengeance.”

When he thinks about the kids who hurt him, though?

“I have more understanding for them than I do for the guards,” he says. “They were ignorant boys. One of them was sadistic, one retarded, and the little kid, Shrimpy, he was always trying to protect himself by taking part. But the guards? They knew exactly what was going on. I remember being on the ground, my pants bloody. I couldn’t get up to go stand in line. Normally they would grab you and pull you to your feet. They just left me there.” The muscles in his neck tighten. “If I were locked in a room with one of those guards, I don’t know what I would do.”

At the same time, he says, he feels “ready to forgive, imperfectly, any of those boys or guards who simply express genuine remorse.” Long pause. “Saying this, I realize it might be my secret, most hoped-for outcome.”

It is also the least likely, and he knows that. “At two in the morning, I keep coming back to ‘Not a fucking thing has changed.’” In juvenile facilities, more than seven percent of residents reported, on a 2018 survey, being sexually victimized during the previous year. Four percent reported use of force or coercion, either by other youth or by staff.

“They get away with it,” Bankston says, “because boys, and men, don’t tell. And because no one wants to know.”

It does not mesh with the masculine ideal.