Argentine heavyweight Oscar Bonavena’s most important fight, certainly his most publicized, was against Muhammad Ali on December 7, 1970 at Madison Square Garden in New York. It was not as exciting as when the first Argentine heavyweight, Luis Firpo, the Wild Bull of the Pampas, fought heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey on September 14, 1923, also in New York. Firpo was knocked down seven times in the first round (ahh, the world of professional boxing before the coming of the three-knockdown rule). That was nothing. What made the fight was Firpo knocking Dempsey completely out of the ring in the same round, famously captured by “ashcan” painter George Bellows. Dempsey, with some help, managed to get back in the ring and knock out Firpo for good in the second round.

What Ali wanted was to be forced to fight a lot of competitive rounds and Bonavena was a durable fighter, hard to knock out or even to knockdown.

There were knockdowns in the Ali-Bonavena fight but not until the 15th and final round in what was otherwise a slog of a fight. At the time, Ali had just returned to boxing after his three-and-a-half ban as a result of his conviction of violating the Selective Service Act and refusing to be drafted. This was his second fight since he was able to get a boxing license again. The first, against “Irish” Jerry Quarry lasted only three rounds. As Patrick Connor writes, “… Ali didn’t seem to view fighting Bonavena as anything more than a necessary step toward getting in the ring with [Joe] Frazier.” (67) Frazier was the big money match that Ali wanted and would get in March 1971 in what would be called The Fight of the Century. But Ali expected Bonavena to be useful.

What Ali wanted was to be forced to fight a lot of competitive rounds and Bonavena was a durable fighter, hard to knock out or even to knockdown. He would last longer than Quarry. Ali could not expect to fight Frazier successfully having only fought three competitive rounds (the Quarry fight) in nearly four years. Ali needed rounds. But Ali was not in good shape for the Bonavena fight. Why would he be? Bonavena was awkward, with clumsy footwork (his flat feet did not make him agile), lacking technique, a clubbing, mauling bruiser. He expected Bonavena to be nothing more than a hard workout. That was largely true. He knocked Bonavena down three times in the 15th round; with the three-knockdown rule in place, Ali thus scored a knockout, which gave him bragging rights over Frazier who fought Bonavena twice without knocking him down, let alone knocking him out. Indeed, the first time Frazier fought Bonavena, the big Argentine knocked Frazier down twice in the second round and would have knocked him out if he had better technique. (“Like a novice, he stifled his punches, killing his chances by pushing forward recklessly,” Connor sums up about the Frazier fight. (31)) Ali succeeded in knocking Bonavena out largely because the Argentine also was not in great shape and was exhausted by the end of the fight. Over the course of his career, Bonavena had some excellent trainers like Charley Goldman and Gil Clancy, but he never listened to any of them. If he had, he probably would have become a champion, or he surely would have beaten Joe Frazier.

Like many boys, Bonavena began boxing as a teenager to deal with being harassed by local toughs. “The awkward Bonavena … stood out even as a teenager,” writes Connor. “He was a heavily muscled boor who wouldn’t shut his mouth, intent on turning attention toward him at every turn.” (5) This craving for attention manifested itself in odd ways. For instance, before his December 1967 fight against Jimmy Ellis in Louisville, Bonavena dressed up as Santa Claus and challenged any sidewalk Santa he encountered in downtown Louisville to fight him. To most Americans, Bonavena was “a foreign boor who mimicked Tarzan yells and threw semi-playful body shots at reporters like Howard Cosell mid-interview. …Bonavena fought like a bully.” (39)

Bonavena was racist, tasteless, and a bit of a free spirit.

He was also a sponge, a mooch. The traditional, stereotypical view of boxing is that the boxer is victimized by his manager, cheated, used, and dumped, used up and punch drunk. Bonavena flipped the script: he used everyone around him. He milked his managers, his promoters, anyone he could put the bite on. Considering how cut-throat a game prizefighting is, no one exactly begrudges him this. This was simply a case of the odd getting even.

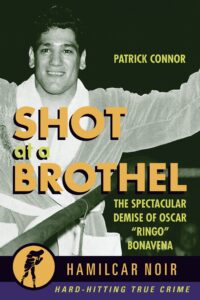

Shot at a Brothel tells, crisply and succinctly, the story of the rise and fall of Oscar Bonavena, a significant, though not great, boxer of the 1960s and 1970s. Like the other books in the Hamilcar Noir series, it shows the underbelly of the world of boxing through short biographies of fighters who sustained tragic ends. All sports, all popular entertainment, have their sleazy side: drugs, gambling, whores of any gender (“sex workers” for the Marxists of the middle class), vapid conspicuous consumption, and on it goes. It is not hard to find this in boxing, a sport with a history of the grotesque, the gruesome, the damaged, the exploited, the strange, and the heartless, with an underbelly that is not close to the surface but rather is the surface. If someone wants all the evils of capitalism on display as theater, boxing is it. Boxing was, at one time, America’s actual film noir.

The traditional, stereotypical view of boxing is that the boxer is victimized by his manager, cheated, used, and dumped, used up and punch drunk. Bonavena flipped the script: he used everyone around him.

Shot at a Brothel also tells the story of Joe Conforte, a ruthless pimp who disguised himself for a time as some kind of activist for sexual freedom and the empowerment of prostitute (he treated the women who worked for him as poorly as most pimps do), and who owned the Mustang Bridge Ranch, one of the most famous brothels of the 1970s. Bonavena was killed (one rifle shot, a .30-06, to the heart) in the early morning of May 22, 1976 at the gates of Mustang Bridge Ranch by Ross Brymer, who worked for Conforte. The circumstances surrounding the shooting are not clear, that is, it is not quite clear why Bonavena was shot. He had been living on and off at the Ranch as his boxing career wound down and he was trying to gain entry to the Ranch when he was killed. He had become close to Conforte’s wife, who made her career as a madam, but it is unlikely Conforte permitted or planned for Bonavena to be shot because of that, even the relationship between Bonavena and Conforte’s wife was sexual. One thing is clear: Bonavena was definitely murdered. No one actually wound up being punished much for it. Not surprising, as we are dealing with the zombie/vampire worlds of boxing and prostitution running headlong into the corrupt, bureaucratic maze of twilight reality called the American criminal justice system. Brymer served 18 months in prison. We shoot broken horses. Why not boxers too? Championship boxing matches almost always occur around 10 or 11 in the evening at the venue where they are taking place. This means that any ambitious boxer worth his salt is always seeking to be the last one standing in the ring at the end of the night.