• The Fighting Frenchman

Minnesota’s Boxing Legend: Scott LeDoux

By Paul Levy

(2016, University of Minnesota Press) 247 pages including index, notes, and photos

• Ali vs. Inoki: The Forgotten Fight that Inspired Mixed Martial Arts and Launched Sports Entertainment

By Josh Gross

(2016, BenBella Books) 299 pages including index and photos

National Football League Hall of Fame coach Bud Grant, born and reared in Superior, Wisconsin, but within spitting distance of Duluth, Minnesota, who led the Minnesota Vikings to four Super Bowl appearances, was a wide receiver on the University of Minnesota football team when Jim Malosky was the starting quarterback. Malosky was boxer Scott LeDoux’s football coach at the University of Minnesota-Duluth when LeDoux, born in Crosby, Minnesota, was trying to become a successful lineman. It might be said that there were far less than six degrees of separation between two Minnesota sports legends.

What LeDoux and Japanese professional wrestler Antonio Inoki have in common is fighting boxing Legend Muhammad Ali in the 1970s, after Ali had re-gained the title by knocking out George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire, in October 1974 and in the process becoming not just a hero but a god to a large number of people across the globe. It was one of those rare instances, because of Ali’s extravagant and generally likable personality and his political symbolism, that an athlete’s personal and professional redemption became a form of redemption for the majority of his vast public, particularly his own countrymen. Both the LeDoux and Inoki fights were unusual in that neither involved Ali’s boxing title (as a result, it is difficult to say whether either fully engaged Ali’s competitive attention): LeDoux fought Ali in a five-round exhibition in December 1977 and Inoki fought Ali in a “mixed martial arts” bout which wound up a 15-round draw. Exhibitions, as a rule, do not have winners and losers, so there was not an ultimate determination by judges or the referee of who won in Ali’s fight against LeDoux. Had Ali won his fight against Inoki, he would not have become Japan’s professional wrestling champion and Inoki would have not become the heavyweight champion if he had won, although only championship fights were designated for fifteen rounds. (This is no longer the case as championship fights are limited to 12 rounds.) Ali and Inoki were fighting for the championship of something beyond what either of them represented as specialized combatants, not for supremacy in the other guy’s sport.

Both the LeDoux and Inoki fights are mere footnotes on Ali’s athletic resume—far from being definitive of Ali’s career or much remembered by the general public or even boxing fans—yet Paul Levy’s biography of LeDoux, The Fighting Frenchman, and Josh Gross’s exhaustive account of the Ali the boxer versus Inoki the wrester dust-up, including a round-by-round description of the fight, give readers another way of looking at these fights that elevate their importance, if not for Ali, then for the men who opposed him in these bouts. In Levy’s book, we see Ali through the eyes of one of his lesser opponents and what fighting Ali, even if only in an exhibition, meant to LeDoux in the totality of his career. In Gross’s book, we, again, in part, see how important Ali was to an opponent but we also learn how this bout redefined professional combat sports in the late 20th century.

It was one of those rare instances, because of Ali’s extravagant and generally likable personality and his political symbolism, that an athlete’s personal and professional redemption became a form of redemption for the majority of his vast public, particularly his own countrymen. Both the LeDoux and Inoki fights were unusual in that neither involved Ali’s boxing title. As a result, it is difficult to say whether either fully engaged Ali’s competitive attention.

LeDoux, of French Canadian extraction, grew up in a small, white, working-class town, his father, a miner, had been, as an adult, forced to fight in bars by LeDoux’s grandfather. As Levy describes it, “Often, Edward LeDoux had his son, who was in his early twenties, fight two men at once. On at least one occasion, he ordered him to fight four ‘or he’d kick his ass,’ Scott LeDoux remembered.” LeDoux’s grandfather was a hard drinking, two-fisted type and clearly an abusive man. LeDoux was the product of a tough guy, highly masculinized environment, the kind of environment from which a hockey player, a football player, or a boxer might emerge. LeDoux was two of three: a college football player and a professional boxer. (He was also a baseball player in high school.) What exacerbated the difficulty of life’s choices and challenges for the young LeDoux was that he was sexually assaulted at the age of 5. Although he managed to conceal this from his parents for years, many of his peers knew or heard something about it, so LeDoux was teased and bullied mercilessly. This of course shaped a personality that became constructed around both fear and rage and led him ultimately to a career in tough-guy athletics, where the test was not simply how much one could dish out but how much one could take. As Levy observed, “… sports offered a kid tormented by peers the chance to be somebody special.” As LeDoux put it in talking about how he felt before a fight: “I was terrified. Before every fight, I worried about everything. I don’t think fighters like to admit the fear factor very much. I was scared to death up until five minutes before they rang the bell. Then, someone would knock at the door and say, ‘Five minutes to go.’ That’s when I lost my fear. I knew I had to go in the ring. It was too late to be afraid anymore.” But, as a college friend said, LeDoux “could get explosive. He had these extremes.” Being in the ring helped LeDoux control himself.

Unsurprisingly, he had a considerable following in Minnesota. Three of his biggest fights in the latter part of his career—against Larry Holmes, Mike Weaver, and Ken Norton, all internationally known fighters who were major drawing cards—were held in Bloomington, Minnesota, which meant LeDoux had enough audience pull as a local fighter to make a promoter think such important fights as these could succeed there financially more than they could in boxing meccas like Las Vegas, Atlantic City, or Madison Square Garden. He fought for some version of the heavyweight title five times, a tremendous achievement, and did not win any of them, did not even come close. He fought such well-known fighters as Leon Spinks (a draw; LeDoux would have been given the decision had Spinks not already signed a contract to fight Ali), George Foreman, (who knocked out LeDoux), Ken Norton (another draw that LeDoux definitely should have won as he had Norton virtually unconscious at the end of the fight), Larry Holmes, (the fact that LeDoux lost this championship bout was not as noteworthy as the bitter exchanges between the two men before the fight, with LeDoux, at times, sounding downright racist, although LeDoux was not, by nature, a racist), and Greg Page, a knock out loss for LeDoux. He was very close to the real life version of Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky, at least, as conceived in the first film of the Rocky series. He said that he did not want to be the token white fighter in an era when blacks dominated the heavyweight division yet in some respects he was. The racial mood of the United States and the emphasis on racial and ethnic difference that has historically been a key marketing device for boxing made even a so-so white fighter worth his weight in gold.

Unsurprisingly, he had a considerable following in Minnesota. Three of his biggest fights in the latter part of his career—against Larry Holmes, Mike Weaver, and Ken Norton, all internationally known fighters who were major drawing cards—were held in Bloomington, Minnesota, which meant LeDoux had enough audience pull as a local fighter to make a promoter think such important fights as these could succeed there financially more than they could in boxing meccas like Las Vegas, Atlantic City, or Madison Square Garden. He fought for some version of the heavyweight title five times, a tremendous achievement, and did not win any of them, did not even come close. He fought such well-known fighters as Leon Spinks (a draw; LeDoux would have been given the decision had Spinks not already signed a contract to fight Ali), George Foreman, (who knocked out LeDoux), Ken Norton (another draw that LeDoux definitely should have won as he had Norton virtually unconscious at the end of the fight), Larry Holmes, (the fact that LeDoux lost this championship bout was not as noteworthy as the bitter exchanges between the two men before the fight, with LeDoux, at times, sounding downright racist, although LeDoux was not, by nature, a racist), and Greg Page, a knock out loss for LeDoux. He was very close to the real life version of Sylvester Stallone’s Rocky, at least, as conceived in the first film of the Rocky series. He said that he did not want to be the token white fighter in an era when blacks dominated the heavyweight division yet in some respects he was. The racial mood of the United States and the emphasis on racial and ethnic difference that has historically been a key marketing device for boxing made even a so-so white fighter worth his weight in gold.

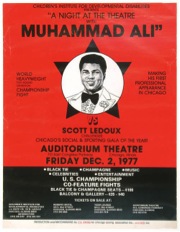

When Ali fought the exhibition against LeDoux on December 5, 1977, four of the champion’s last ten opponents (going back to 1975) had been white (Chuck Wepner (the true inspiration for Rocky, Joe Bugner, Jean Coopman, and Richard Dunn). They were all clearly inferior to the black fighters that Ali fought during the same period—Ron Lyle, Joe Frazier, Jimmy Young, Ken Norton, and Ernie Shavers. Ali considered these white opponents as easy matches between his more difficult bouts with the black fighters who were greater competitive threats. Ali also fought Uruguayan Alfredo Evangelista during this period, another easy, inferior fighter. Ali saw the exhibition with LeDoux as not very challenging, not even competitive, which was the proper way for him to see it. Exhibitions are little more than sparring or practice sessions. Ali entered the match in poor condition. “For me, it was unbelievable. To be in the ring with Ali …” said LeDoux, who was hoping that the exhibition would lead to a shot at Ali’s title after Ali beat Spinks later that year, which, in fact, an aging Ali was unable to do. “In the first round, I hit [Ali] right in the chin, LeDoux remembered, “That should never have happened. I would never have been able to hit Ali in his prime. You could see he didn’t care. I had him bleeding from the nose and mouth after two rounds. How could that happen? He was really puffy and wasn’t exactly floating like a butterfly. I had big gloves on, but I could still hit Ali at will.” Ali was clearly lazy and bored, an attitude he took into the ring on February 15, 1978, against Leon Spinks, who beat him decisively on points. In the strange ways of professional boxing, because Ali lost to Spinks (he beat Spinks later that year to regain the title), LeDoux lost any chance he had of fighting an out of shape, uninspired, deteriorating Ali for the championship.

LeDoux, like most main event fighters with some substantial paydays, wound up spending all the money he made, every last penny of it, largely on expensive indulgences, and left the ring broke. In his later years, he worked as a referee, a salesman, a motivational speaker for business seminars, and a local politician. He finally confronted the man who had molested him as a child, forgiving him for what he had done, and thus bringing some achieving some measure of moral reckoning with his assailant and some measure of peace for himself. In January 2009, he was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. He died on August 11, 2011 at the age of 62. Whether his condition was in any way brought about because of the punishment he took in the ring is not clear.

As previously mentioned, it is during this same period as the LeDoux/Ali exhibition, that Ali participated in the most unusual bout of his career, against wrestler Antonio Inoki in Tokyo. While Ali was clearly the most famous boxer on the planet at the time, it was arguably the case that the charismatic, lithe, and intense actor Bruce Lee, who died tragically in 1973 at the age of 32, was, in the 1970s, nearly as well-known as a martial artist. Singer Carl Douglas’s “Kung Fu Fighting” was a huge Top-40 hit; and Hong Kong “kung fu” movies were the rage in the United States. Indeed, one of the most popular television programs of the time was an offbeat western starring David Carradine called “Kung Fu”(1972-1975), originally conceived by Bruce Lee as a starring vehicle for himself, about an orphaned American boy in China who becomes a Shaolin priest and winds up traveling across the American West. With the American popular imagination so taken by Asian martial arts, particularly various forms of Korean, Japanese, and Chinese karate or striking combat forms but even, to some extent, with judo, ju-jitsu, and other forms of Asian grappling, it is not surprising that boxing promoters might be struck by the notion of pouring old wine in a new bottle. It had long been debated, since the rise of Marquis of Queensberry rules in boxing, among knowing coves of combat sports whether a boxer could beat a wrestler. In the 1970s, when so many combat forms achieved prominence with the western public, it would be expected that some major east-meets-west encounter could be used as a forum to determine who is the best fighter or which combat art is superior. Could Ali, the best boxer of his time and arguably the best boxer ever, beat someone who specialized in another combat sport? Thus, the Ali versus Inoki match was born, the fighter boxing the wrestler for “the martial arts championship of the world.”

With the American popular imagination so taken by Asian martial arts, particularly various forms of Korean, Japanese, and Chinese karate or striking combat forms but even, to some extent, with judo, ju-jitsu, and other forms of Asian grappling, it is not surprising that boxing promoters might be struck by the notion of pouring old wine in a new bottle. … Could Ali, the best boxer of his time and arguably the best boxer ever, beat someone who specialized in another combat sport?

Gross provides the extensive history of what led up to this fight, including a historical account of wrestling and the martial arts in the United States, Japan, and Brazil (where Inoki spent a good deal of his youth and developed as an athlete). Readers learn about previous matches between boxers and wrestlers, nearly all of which were won by the wrestlers. A boxer’s best chance of beating a wrestler is to strike quickly and knock him out. If the boxer fails to do this, the wrestler is sure to grapple him to the canvas where the boxer, with no knowledge of wrestling holds and hindered in any case by his gloves so that his hands are practically useless except for striking from a standing position, will be easily pinned and defeated. (Indeed, Madison Square Garden audience for the Ali/Inoki fight, which they saw on closed circuit, saw a live preliminary bout between boxer Chuck Wepner and wrestler Andre the Giant which ended with Andre throwing Wepner out of the ring. That fight inspired an early scene in Stallone’s 1982 Rocky III where Rocky fights wrestler Thunderlips, played by Hulk Hogan, but things are reversed and Rocky throws Hogan out of the ring.)

That fight between Wepner and Andre was scripted or what is called in wrestling “a work.” In other words, it was a fake fight. The fight between Ali and Inoki was a shoot, in other words, a real fight, completely unscripted. Ali refused to participate in a fake match for fear it would damage not only his integrity as a sportsman but also boxing itself, which had long suffered under the cloud of fixed fights. (Many still believe that Ali’s two fights with Sonny Liston were fixed, although Ali himself in never implicated. The common belief is that Ali was on the up and up but Liston was not.)

Perhaps a shoot versus a work is a distinction without a difference. Gross quotes professional wrestler and mixed martial artist Josh Barnett about how Inoki understood the difference: “Whether it was working or shooting, Inoki’s mindset was ‘real.’ You’re really doing everything real all the time, in Inoki’s mind. It’s just whether or not you’re actually shooting, having a real fight, or working, doing a predetermined match. If you treat it real, keep it real, keep your mind real, then whatever it I s you do out there will come off as real, and the people will be more engrossed and involved in it and they’ll feel the meotion of the match more than the moves that you’re doing.” In short, it is the integrity, the authenticity of the performance that matters. After all, everything in combat sports is acting, but not just acting.

Why Ali took the match is something of a mystery. Gross emphasizes that Ali had little to gain and everything to lose by having a match of any sort, real or fake, with a wrestler. Ali’s people did not want him to fight Inoki because they feared injury: the wrestler might snap Ali’s leg in a hold or break his shoulder in a fall. But Ali was promised $6.1 million, more than he had been paid to fight either Foreman or Frazier. He had an entourage of more than 50 people, which required that Ali needed to get as money as he could from his fights to support his lifestyle. Money was more than an incidental motive. (Gross points out that Ali received only $1.8 million for the Inoki bout. It turned out to be a severely bad business deal for him.) Moreover, Ali may have thought, indeed, did think he would easily knock out the Japanese wrestler, that the fight would be lark. (By 1978, two years after the Inoki affair, the myth of Ali had grown to such an extent that DC Comics published an oversized special edition entitled Superman versus Muhammad Ali in which the Louisville Lip beat the Man of Steel. )

In short, it is the integrity, the authenticity of the performance that matters. After all, everything in combat sports is acting, but not just acting.

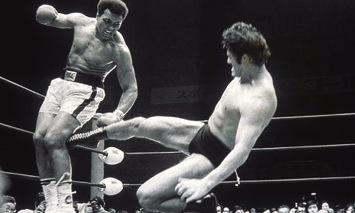

The fight itself was a disaster, in part because the rules were never clear. Ali tried to find a way to hit Inoki while the wrestler scooted along the canvas, kicking Ali’s legs bloody, while trying to sweep the fighter’s feet from under him. Ali exhorted his opponent to stand up and stop fighting “like a girl.” Inoki, who knew he had no chance against Ali upright, invited the boxer to grapple with him on the canvas where he would have snapped Ali in two. Each man fought in his own physical plane which made for a completely non-competitive event. The problem was that neither man had sufficient skill in the other man’s art to have a truly “mixed martial arts” contest. A bareknuckle prizefighter from the 18th century would have been able to grapple with Inoki because boxing under London Prize Ring Rules had a great deal of wrestling in it, in part, because a bare fist cannot strike continuously with breaking. (Human hands are fairly fragile.) The advent of gloves eliminated the need for wrestling in prizefighting as gloves provided the necessary protection for continual striking. The only remnant from bareknuckle days is the clinch, where a boxer pins his opponent’s arms to keep him from striking. But clinches are brief interludes that referees quickly break up and a clinch does not involve trying to get one’s opponent in a some sort of hold to force submission, as it might in the bareknuckle days. A boxer, unless he receives some considerable training in grappling and holding, cannot remotely hope to beat a wrestler at the wrestler’s game. For his part, the wrestler must avoid being hit by the boxer, but unlike a boxer, a wrestler, while trained to use feints, is not trained to slip, avoid, or counter punches as a boxer is. For a boxer, a wrestler is far easier to hit than another boxer would be, as long as the wrestler is upright. A wrestler cannot hope to beat a boxer at the boxer’s game unless he gets some serious training in striking and counter-striking. The Ali-Inoki, doubtless, as Gross suggests, fired the sporting public’s imagination for mixed martial arts in a way that exceeded previous interest in such matches. But mixed martial arts have evolved into a sort of free-form fighting that includes techniques from karate, boxing, judo, and wrestling with both combatants equally skills in aspects of these various fighting arts. Mixed martial arts and “ultimate fighting” now threaten to eclipsed boxing, a troubled sport that has increasingly managed to marginalize itself, as the main combat sport of the United States.

Inoki fought 20 mixed martial arts contests, including pinning Leon Spinks about a decade after the fight with Ali. Inoki won 16, lost one, and had three draws. How many were shoots and how many were works? Who knows? Ali fought no other mixed martial arts matches after Inoki, who so bloodied and battered Ali’s legs that the fighter could barely walk after the bout. Gross is correct to point out that such a beating only reduced Ali’s mobility which was diminishing with age in any case. Before the Inoki fight, Ali had won five of his previous seven bouts by technical knockout or knockout. After the Inoki fight, he would not knock out another opponent. Age had taken a lot out of Ali but the broken blood vessels in his legs that resulted from Inoki fight did not help any. At any rate, Ali was smart enough not to repeat the Inoki , mixed martial arts mistake. He knew enough to quit while he was behind.