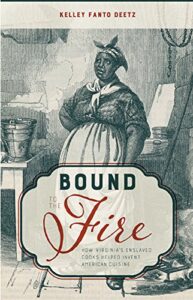

With Bound By Fire Kelley Fanto Deetz joins the current and lively conversation celebrating the many contributions of America’s enslaved chefs. In recent years books like Psyche Forson Williams’s Building Houses Out of Chicken Legs and Jessica B. Harris’s High On The Hog, along with other publications, have chronicled the history of the African American men and women who worked for years with no or little remuneration. The efforts of black cooks in white-owned kitchens were usually accompanied with patronizing tributes, if acknowledged at all. Such leading actors on the hearth, in contrast to the ones heralded in “mammy” cookbooks or those individuals whose efforts were carefully recorded by family and friends, have gone little noticed. Deetz’s Bound By Fire sets out to address our on-going gastronomic rehabilitation by focusing on the story of Virginia’s enslaved plantation cooks. She has taken on a difficult task, for those unsung chefs of the antebellum and colonial era left no cookery compilations or published sources behind. To dig deep into the culinary history of the United States Deetz must turn initially to the published record, of course, but she does her readers a service by choosing to interpret the material culture and architecture surrounding the men and women who helped build Virginia’s famed “cuisine and hospitality … and the creation of Virginia’s hospitable lifestyle” (3-4). How does one write the legacy of Virginia’s enslaved Black cooks whose lives did not allow them to pass down hand-written compilations of their favorite dishes?

To tell the less than savory back story of Virginia’s unsung culinary actors Deetz divides her monograph into five main sections: “In Home,” “In Labor,” “In Fame and Fear,” “In Dining” and “In Memory.” Preceding these chapters with the introductory “In Myth”, the author proceeds to a nostalgia-busting, record-correcting account. Arranging the volume into themes avoids a strictly chronological overview, an asset when considering the narrow range of available documentation: there are virtually no extant texts by any of these men or women, save for a scant few items by James Hemings, Thomas Jefferson’s Paris-trained chef de cuisine. Deetz consequently mines white-authored manuscripts whether autobiographical, epistolary, or cookery; published records; and secondary sources. To document the transmission of African American contributions to our national cuisine, Deetz points, for example, to the inclusion of African diasporic foods in white-authored cookbooks like Mary Randolph’s A Virginia Kitchen (1824); there the white plantation mistress includes a recipe for okra, a vegetable brought to North America from Africa. When that and similar recipes become commonplace through manuals such as Randolph’s, Deetz writes, they attest to an unwitting assimilation of African diasporic foods, for “once a recipe makes its way into a cookbook, it has passed a cultural test” (122). Set down as tested and desirable dishes, white readers are taught that these new foods should be included in their menus, that there should be something black, as it were, on the table to testify to a cultured meal. African produce like okra and sesame seed thus became detached from its origins. And while the diasporic nature of those and other foods went unheralded for some time, they have not remained so, as scholars like Judith Carney and Richard Nicholas Rosomoff have shown.

Set down as tested and desirable dishes, white readers are taught that these new foods should be included in their menus, that there should be something black, as it were, on the table to testify to a cultured meal. African produce like okra and sesame seed thus became detached from its origins.

Stepping away from the evidence of African American food ways on the printed page, Deetz turns to the physical description of the enslaved chef’s world. Living in or above the plantation kitchen might have provided a modicum of privacy and family togetherness for enslaved cooks, but they also had to endure the ferocious heat of a never-extinguished hearth, a daily brutal ordeal during Southern summers: “the hearth fire burning at over 1,000 degrees would make the kitchen tortuous in the summer months” (46)—how much could such an ordeal be balanced by the relative comfort of the same quarters during a Virginia winter? Throughout the year the plantation kitchen held “vats of fermenting meat, drying blood, fish guts, and rotting vegetables” (46) making the so-called privilege of house servitude a very mixed blessing. Plantation architecture reveals how the planter class literally set boundaries between the free and the enslaved, but black captives could shape that space as well, using ironwork, oyster shells and crystals. Her analysis of the physical spaces of Virginia plantations aims to illustrate the way “material culture[can show how] … cooks created a black landscape in a white world” (3).

Deetz intrigues the reader with a promise of “exceptional cooks” whose legendary exploits brought fame to chef and owner alike—readers will be reminded of the tragic life of James Hemings (more robustly covered in Gordon-Reed’s The Hemingses of Monticello) and find a longer narrative of his predecessor Hercules, chef to George Washington. Their stories sadly diverged: Hemings committed suicide before Jefferson was elected to the presidency; Hercules, shuttled north and south by new president Washington, made his escape on our first president’s birthday. Their stories are contrasted with would-be and accused poisoners in the plantation household, like one Shadrach Wilkins and a couple named Warner and Tabby. Yet the lack of an extended discussion about these accused men and women makes the link between poisoning and cooking in need of further support, and the author’s acknowledgment that “one wonders why more cooks didn’t try to poison their masters” (98) appears to concede there remains more to say. Mere access to a kitchen does not a chef make.

In Deetz’s enthusiasm to assert the now-incontrovertible contributions of enslaved African Americans in Virginia to the national cuisine, she sometimes overstates her case. A case in point is when she claims, “The currency of proper food was so important that the teaching of basic reading [to the cooks] became essential to guarantee culinary delight,” yet no supporting evidence is provided. A former trained chef herself, Deetz asserts that high-level cuisine demands a certain level of expertise—“the teaching of basic reading became essential to guarantee culinary delight”—but a skilled deployment of math and ingredients might not be equated with literacy per se. And while it is true that Virginia slave-holders may have occasionally enabled a degree of slave literacy to facilitate the running of their plantations, by 1831 state statute forbid such knowledge, a situation ensuring marginal black literacy, as Antonio Bly and Janet Cornelius have documented. Malinda Russell’s 1861 cookbook might offer some reinforcement regarding the literacy rate of enslaved cooks—although Russell, born to a slave mother in Tennessee, was free.

… she [Deetz] questions the lore that declared the placement of the plantation kitchen away from the main house was due to fear of kitchen fires; she argues that just as likely was the planter’s desire to obscure the discomfiting sight of accomplished black cooks and the concomitant acknowledgment of white reliance on that expertise; doing so promoted the mythology of a gracious, tension-free Southern hospitality.

Most enjoyable is the history of the mechanics and physical spaces of the plantation household, a route perhaps suggested to Deetz by the paucity of documentation but revelatory nonetheless. The author tells us how Jefferson’s reluctance to acknowledge the labor of his slaves led to such architectural novelties as a “tiered table that could … [enable] a waiter-less dinner” and “the most modern and bizarre gadgets to allow the presentation of food without blackness … shield[ing] his guest from the black presence” (36-37). And she questions the lore that declared the placement of the plantation kitchen away from the main house was due to fear of kitchen fires; she argues that just as likely was the planter’s desire to obscure the discomfiting sight of accomplished black cooks and the concomitant acknowledgment of white reliance on that expertise; doing so promoted the mythology of a gracious, tension-free Southern hospitality. Enlivened by good illustrations, including a reproduction of the (attributed to) Gilbert Stuart portrait of Hercules, Deetz’s assertive little volume provides a lagniappe to the burgeoning field of Black culinary studies.