The word “freedom” floats in American rhetoric like a Berndnaut Smilde cloud in an empty ballroom. People see meaningful figures in it, but it shreds in the slightest breeze.

Ronald Reagan began using the word in the contemporary American political sense in 1964. In the television speech titled “A Time for Choosing,” made on behalf of Barry Goldwater’s presidential election campaign, Reagan jiggered the word in a way that would define the rhetoric of the American right into our time.

Reagan was competing with the civil rights movement about the deployment of the word freedom. For the civil rights movement, the slogan was “Freedom Now.” Reagan’s speech, which came too late in the campaign to do Goldwater any good, was delivered the year after the centennial of the Emancipation Proclamation. The word freedom was in the air in many competing ways at this time.

“You and I are told increasingly we have to choose between a left or right,” Reagan said. “Well I’d like to suggest there is no such thing as a left or right. There’s only an up or down—[up] the ultimate in individual freedom consistent with law and order, or down to the ant heap of totalitarianism.”

A recent political meme said, “[I]s there anything more capitalist than a peanut with a top hat, cane, and monocle selling you other peanuts to eat[?]”

What he called freedom was a negative quality: freedom-from—in this case, constraints on business by meddling government, which must be kept small by starving it of tax revenue (except for approved cases such as the U.S. military, that great socialist program).

“[O]utside of its legitimate functions government does nothing as well or as economically as the private sector of the economy,” Reagan said. The free market would provide, and if it did not provide to all, well, it would adjust, eventually, because the market was rational. There were no problems, only opportunities.

By implication, “no such thing as a left or right…only an up or down” meant all politics or economic theories to the left of the post-JFK, reforming American right were gateways to totalitarianism, by which he meant “communism.” (Reagan’s own path to reformation from his start as a Democrat included an appearance as a “friendly witness” at the HUAC proceedings.)

In “A Time for Choosing” Reagan said that, in Vietnam, “We’re at war with the most dangerous enemy that has ever faced mankind in his long climb from the swamp to the stars, and it’s been said if we lose that war, and in so doing lose this way of freedom of ours, history will record with the greatest astonishment that those who had the most to lose did the least to prevent its happening.”

Reagan’s speech came to be called, admiringly, “The Speech,” because it not only gave words to a movement but also put his political career on the national stage and became an origin story for his reputation as the “Great Communicator.” Though Goldwater lost, badly, to LBJ that year, Reagan’s notion of freedom as absence would underwrite the long Nixon era’s beliefs in supply-side economic theory and the magical thinking of self-help positivity and the prosperity gospel.

Reagan doubled down on it through his own presidency. When he addressed students in the Soviet Union in 1988, the year before the Berlin Wall fell, he used variations of “freedom” and “free” twenty-one times in less than 30 minutes (and managed to hit the other note in the chord: “Americans are one of the most religious peoples on Earth”).

“Freedom is…the continuing revolution of the marketplace,” he said. “Perhaps most exciting are the winds of change that are blowing over the People’s Republic of China, where one-quarter of the world’s population is now getting its first taste of economic freedom.”

Many U.S. conservatives are less excited now about the sea change of China’s economic power, revealing the hypocrisy baked into capitalism: Wealth is proof of the rightness of the unfettered project, until someone else’s wealth threatens my interests, then a solution must be found.

But capitalism offers ways forward, at least in the short term. A business (or a nation whose “chief business…is business,” as Coolidge said) can advertise, downsize, acquire, restructure, refinance, take loans, demand concessions, sell assets or stock, lobby for favor, etc. Profit—not, say, civility, mutual cooperation, tradition, peace, a true bottom line, or even adherence to the spirit of the law—is the main goal.

“Freedom is the right to question, and change the established way of doing things,” Reagan told the students at Moscow State University. “It is the right to put forth an idea, scoffed at by the experts, and watch it catch fire among the people.”

He did not mean an idea such as universal healthcare. He was not praising the questions of poets or the suggested changes of philosophers, but the freedom that was the right of “entrepreneurs, men with vision.” He meant the ruthless spirit of the profit motive, which may embody “the ultimate in individual freedom” but is not necessarily “consistent with law and order.”

Once the froms are eliminated, what will you do with being free? As the US Department of Justice notes:

“Alleged and actual crime and wrongdoing during the Reagan administration exceeded that of previous presidents, including Nixon, Harding, Grant, and Buchanan. Between 1980 and 1988, over 200 individuals from the Reagan administration came under either ethical or criminal investigation. The political and economic climate of the 1980’s was ripe for the savings and loan scandal, the most costly financial public policy failure in U.S. history. Deregulation during the Reagan years created a climate of criminal opportunity for speculative and illegal financial activities …[i]nsider trading scandals [and] rigged stock market trading. The Reagan administration was also plagued by scandal in the Environmental Protection Agency, political and corporate corruption involving the Wedtech Corporation, illegal Pentagon procurement activities, and the Iran-Contra affair.”

A recent political meme said, “[I]s there anything more capitalist than a peanut with a top hat, cane, and monocle selling you other peanuts to eat[?]”

• • •

The notion of freedom-from was in my mind as I attended the four-day Socialism 2023 Conference in Chicago over Labor Day weekend.

The American left has always had its own image of what society must obtain freedom from: Mr. Peanut. Indeed, panelists and speakers at the conference were good at identifying what they believed caused oppression—mostly corporate capitalism and its enabling politics, with admixtures of racism, gender and disability bias, nationalism, colonialism, and fascism—but few offered specific, practicable paths from that swamp to their own stars, let alone visions of how the bigger world might look once they defeat what oppresses us.

Put another way, the right has always had a plan to get things their way, even with leftists in their midst. We know what their world looks like. Most of us live in it. The American left, which imagines a world of international comradeship, has not realized a cohesive plan, in part because the right (and factions within “the left”) will never cooperate.

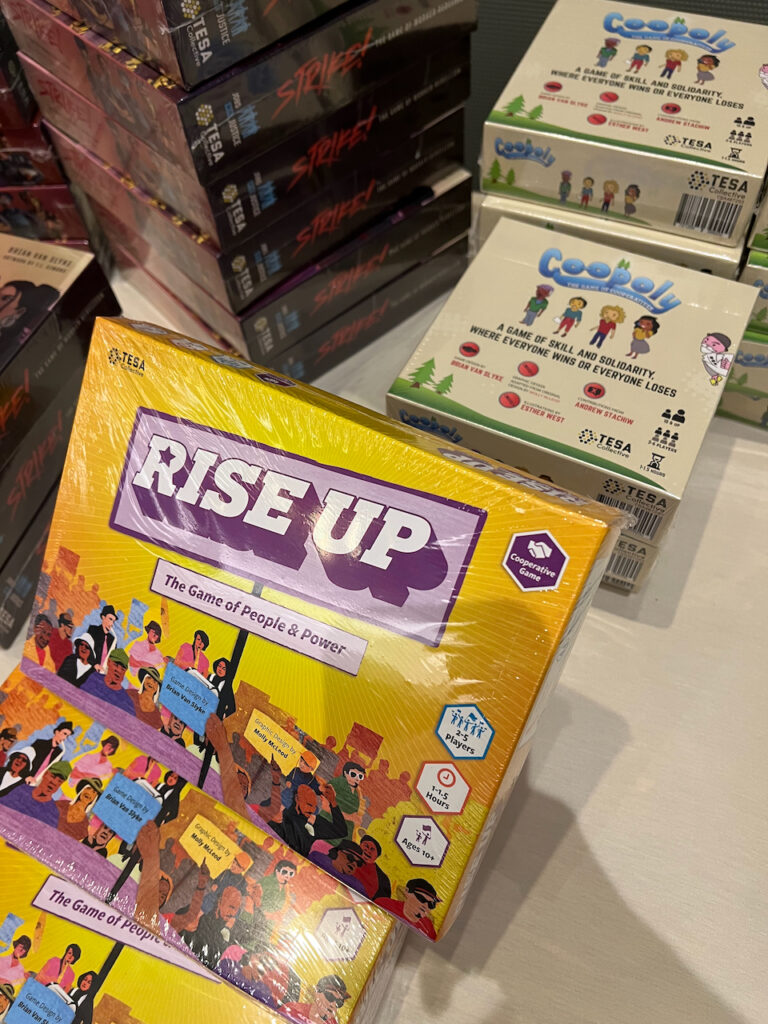

Socialism-themed game offerings at the Haymarket book fair. (Photo by John Griswold)

To be clear, Socialism 2023 was not a political conference in the way that CPAC Dallas, the Conservative Political Action Conference I attended last August, was a pre-primary, election-themed event. At CPAC, most of the MAGA stars made their turns, culminating in the keynote speech by Donald Trump, who spoke as the presumptive Republican nominee for President and was backed by a conference straw poll that put him firmly in the lead among would-be party rivals, though he was still fourteen weeks from announcing. He walked off stage to the Sam & Dave song “Hold On, I’m Comin’.”

Conservative politicians and wonks spoke repetitively, insistently, and specifically on using the existing system to gain more power. Attendees were given their marching orders: get out the vote, register as poll watchers, prepare to initiate or support legal challenges to elections and, if need be, get loud en masse to confuse things. (There had been little consequence then to the January 6th storming of the Capitol, and one of the sessions on the main stage was called “We Are All Domestic Terrorists.”)

Socialism 2023 was not a political conference in the way that CPAC Dallas, the Conservative Political Action Conference I attended last August, was a pre-primary, election-themed event.

As I wrote on the first day of CPAC, “[T]he speakers drummed it into the crowd: You may have had a favorite candidate in the primaries who has lost, and we may believe in different aspects of conservatism, but now is the time to pull together to beat the Democrats, liberals, progressives—the ‘socialists’ who are against us.”

At the Socialism 2023 conference no one mentioned voting, because that is a process of the system. The word does not appear in program listings for any of its 118 panels or three plenaries. Most of the sessions I saw were about human rights issues such as housing, immigration, and the “carceral state.” I heard one mention of the Writers Guild strike.

Neither Bernie Sanders nor Cornel West, who is signaling a presidential run on the Green Party ticket in 2024, attended. The conference stars were activist and academic Angela Davis (who last ran for office on the Communist Party USA’s ticket twice in the 1980s) and activist and bestselling author Naomi Klein. Davis and her recent book’s co-authors spoke on prison abolition and anti-capitalist feminism. Klein spoke on her latest book, Doppelganger: A Trip into the Mirror World, which was about to drop.

And though many presenters’ messages were complex and interesting, it seemed notable that Davis, a lion of the left, said, “You know, I’ve been thinking that we should have known that there was going to be a backlash [from the ruling class]…. So, I’m again self-critical, because we did not do the planning we should have.”

Leftist lion Angela Davis spoke in the opening plenary on abolition feminism. (Photo by John Griswold)

Klein said in her address, “[M]any of us would agree that this is not a moment for cheerleading or self-congratulation for the left. […] The new landscape is objectively more perilous, more monstrous, than the one left behind. […] [W]e are in the teeth of a machinery that shrugs at, chooses not to prevent, or actively encourages mass death. […] [I]f we want to understand why [authoritarian movements are] surging in the way that they are…[if] we want to understand how right-wing conspiracy culture is redrawing maps in country after country, I think we need to look at the backing created by decades of often-successful head games to crush the left. And also the vacuums created by ways that we on the left have crushed ourselves without anyone’s help.”

Daniel Faber, Professor of Sociology at Northeastern University, spoke on the panel “The Environmental Injustices of Capitalism.” He said the “tremendous paradox” of environmentalism was that it is one of the most, if not the most, powerful movements within the left. Nineteen million people belong to environmental organizations, and 19 major environmental statutes have been passed over the years. “Despite these victories, the movement is losing the war,” he said.

N’Tanya Lee, on the National Coordinating Committee of LeftRoots, spoke on the panel “Building Socialist Organization and Strategy in the Twenty-First Century” about “how political forces can build the path to shift the balance of power on an ever-changing terrain to defeat opposing forces—because we actually have an enemy—so they can carry out revolutionary change. […] [O]ne of the most key pieces of the strategy is an honest and concrete assessment of the system that we’re in…. [T]he left tends to overestimate our power, and this mis-assessment has been devastating—has costs lives, frankly.”

At the Socialism 2023 conference no one mentioned voting, because that is a process of the system. The word does not appear in program listings for any of its 118 panels or three plenaries.

Aerris Newton, Community Organizer at Planned Parenthood of Tennessee and North Mississippi, said there was a need on the left for “some of the things that within our movement have been lacking—things like social intelligence, emotional intelligence. You know, it can’t just be all of us yelling and screaming at each other. … [Y]elling and screaming doesn’t really work very much a lot of the time.”

Attendees wanted freedom from the existing system but admitted its dominion (the “dom” in “freedom”) and the movement’s current lack of large-scale agency in it. Despite the conference’s message of hope, and its community-building and -empowering intent, the underlying mood was defeatist.

• • •

Another big difference between the conferences was that CPAC was hosted by the American Conservative Union, a lobbying organization that also endorses and funds conservative candidates. The Socialism Conference was hosted by Haymarket Books, a publishing company founded in 2001 to offer books “that contribute to struggles for social and economic justice [and strive to be] a vibrant and organic part of social movements and the education and development of a critical, engaged, and internationalist Left.”

Haymarket also enlisted seventy-five “endorsing organizations” for the conference, such as Muslims for Just Futures, Jacobin magazine, and Science for the People. But the only big national organization I saw was the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA) which handed out flyers and had a meetup offsite at Pizano’s Pizza & Pasta.

The Haymarket Books book fair was a big draw at the conference. (Photo by John Griswold)

The DSA is not a political party but became the largest socialist organization in the United States when it grew from 6,000 members, before Bernie Sanders’ 2016 presidential campaign, to about 95,000 within three years of the 2018 election to Congress of DSA members Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Rashida Tlaib, and Ilhan Omar. (DSA member Cori Bush, the other member of the media-savvy progressive “Squad,” was seated in 2021.)

Attendees wanted freedom from the existing system but admitted its dominion (the “dom” in “freedom”) and the movement’s current lack of large-scale agency in it. Despite the conference’s message of hope, and its community-building and -empowering intent, the underlying mood was defeatist.

DSA hopes to alter corporate America with pushes for more regulation and the strengthening of labor unions. They are behind the Green New Deal and support causes such as student debt cancellation. The organization has been especially popular with millennials. (A 2019 poll showed 50 percent of millennials “viewed socialism positively.”)

By the time of the conference, the DSA had lost 20,000 members again, but The New Republic says there are “close to 160 Democratic Socialists of America-backed politicians in elected office nationwide.”

National Director Maria Svart told CNN there are institutional and structural barriers for organizing outside the two-party system in the US, and that DSA enjoyed “the flexibility of being within the left wing of the Democratic Party, but also being outside of it.”

“We see our role now as shifting…the acceptable discourse,” Svart said, “while also organizing people and building concrete power with a politically aware grassroots base that understands who the enemy is and is willing to hold politicians accountable. But that flexibility is important.”

Shifting the discourse has had an effect in the past. As Adam Hochschild says in The Nation, “[S]ome of President Theodore Roosevelt’s modest moves to regulate business and break up trusts were, in fact, designed to steal a march on this country’s socialists, whom he feared….” The popularity of Bernie Sanders’ plank to cancel student debt seems to have shifted Biden’s policies.

Svart said, “So many people in DSA do want to build a third party, but we also know that you can’t do that without an organized base. And we’re not there yet.”

Kristin Roberts, Chicago Teachers Union, spoke at the open mic after the Josh On talk. (Photo by John Griswold)

The Green Party of the United States is a third party associated with eco-socialism and libertarian socialism. (Noam Chomsky identifies with libertarian socialism—not to be confused with the common use of “libertarian” in the United States, meaning right-libertarianism.) In 2022 the Green Party registered 234,000 voters nationally, .19 percent of the total. There are at least 143 Greens in office nationwide, though Green Party presidential candidates Ralph Nader and Jill Stein were accused of “spoiling” the elections of Democrats Al Gore (2000) and Hillary Clinton (2016). There are concerns among Democrats about Cornel West in 2024.

The Socialist Party USA has some 1,500 members, with none in national office and only four at the local school-board level.

The only references I heard to the classical definition of socialism—ownership by workers of the means of production—were self-effacing. One was followed by soul-searching about what “workers” could possibly mean in the digital gig economy.

Attendees and presenters at the conference self-identified variously as socialists, social democrats, democratic socialists, comrades, generic “communists,” Marxist-Leninists, Trotskyists (the vein of the organization Socialist Alternative), and an anarchist or two. Many in the sessions wore T-shirts for local labor or other activist groups and self-identified as members. There seemed to be an inordinate number of public schoolteachers who rose to speak at the microphones during Q&As and spoke well. (The political jargon from many others was much worse than at CPAC, however.)

The only references I heard to the classical definition of socialism—ownership by workers of the means of production—were self-effacing. One was followed by soul-searching about what “workers” could possibly mean in the digital gig economy.

• • •

Both CPAC Dallas and Socialism 2023 were mixes of community-college lecture, coffee-house talk, and circus spectacle. (CPAC had a fake jail cell with an actor portraying a sad-sack January 6th insurrectionist; Socialism 2023 had radical drag queens, one of whom told me she was Nancy Reagan and insisted I not tell Ronny she was there.)

Both groups were intent and serious and hopeful and sometimes angry in their own settings. But only one had any sort of plan for freedom-from the power of the other group.

This hit me on the first full day of the Socialism conference in a presentation by Josh On, a freelance designer from San Francisco, titled “What and Who Is the Ruling Class?” The conference program marked it with a red flag, meaning “great introduction” to a topic.

Twenty years ago, On created “interactive mapping systems that aim to provide a glimpse of some of the relationships of the U.S. ruling class (They Rule)….” His talk used slides and animated infographics from his site to explain “why some people have more power to make important decisions that affect us all,” and to reveal “who they are and how they rule today” through “an analysis of the structural relations that cement their rule….” As with all good design, his project made the data visually attractive and seemingly efficient.

His narrative (following V. Gordon Childe) began with how you cannot have a ruling class without surplus. Until the development of agriculture, he added, when we began to stay in place, humankind was more egalitarian, and though we “resisted hierarchies for thousands of years,” new power structures built on the hoarding of surpluses led to the “oppression of women, bastardy, and domination.”

On offered a few statistics that seemed to point to the machinery of power now. One slide about the directors of the top-100 U.S. companies was titled “Mostly Old White Men,” but it showed the number of female directors increasing from 13 percent in 2001 to 31 percent in 2021—still disproportionate, but honestly better than I thought it would be, and improving.

Both groups [CPAC and Socialism 2023] were intent and serious and hopeful and sometimes angry in their own settings. But only one had any sort of plan for freedom-from the power of the other group.

Another slide said, “19% of directors on the boards of the top 100 US companies went to Harvard Business School.” I sat trying to parse this—19 percent as one-fifth of the top 100…Harvard MBA currently ranked No. 5 by US News—though the precise meaning of this concentration of power was left unarticulated. In any case, the data On was using was twenty-two years old, and I found myself unwilling to cogitate any harder.

Another slide showed the purported link between the Trump administration, the George W. Bush administration, and the top 100 companies. The graphic showed only one direct connection: Elaine Chao, wife of Mitch McConnell, who was Secretary of Labor for Bush and Secretary of Transportation for Trump. For an overpowering sense of how reductive it would be to make Chao the key agent of multi-administration power, try reading her biography on Wikipedia in full, clicking and reading all the links as you go.

The main feature of On’s They Rule was the ability to “explore” connections among the boards of Fortune 100 companies. On admitted his site was “not the whole story,” and that it “made sense” board members were connected to each other, but he let the site run on random mode, and it mapped some connection from Target Corporation through the boards of several other companies to Amazon. PepsiCo sat in the middle of that path. On pointed this out as an oddity but added, “You can come up with your own conspiracy theories.” The audience laughed.

He was joking, but why give the appearance of implication if there was no significance? I think the audience laughed because the Pepsi narrative, generated with apparently real data, sounded as paranoid as the idea that there was a child sex-trafficking ring run by Democratic elites out of a pizza joint called Comet Ping Pong.

Naomi Klein’s new book deals with this phenomenon. As she pointed out in her talk, “The Conspiracy is Capitalism: Making Sense of the Paranoid Right—and the Tasks of the Left,” right-wing conspiracists came up with conspiracy theories that were ridiculous—international cabals trafficking children for adrenochrome—but which were often built on a sort of emotional truth. Children are put at risk every day in our society, Klein said, especially by bad policy affecting millions.

Similarly, On’s thesis is obviously true at some level. There is a group or class of people in the United States who have inherited or accumulated outsized resources and therefore have the power to affect others in this country or the world. It also should be obvious that many of them know each other professionally and socially, and that this aids them in getting even more resources. The rich get richer, we grouse. Soft drinks are bad for us, we acknowledge and begin to squint at Pepsi to see how far it all goes.

He [Josh On] was joking, but why give the appearance of implication if there was no significance? I think the audience laughed because the Pepsi narrative, generated with apparently real data, sounded as paranoid as the idea that there was a child sex-trafficking ring run by Democratic elites out of a pizza joint called Comet Ping Pong.

Meanwhile, as Sam Knight says in The New Yorker, “About a third of global carbon emissions come from the construction industry and from the energy used to heat, cool, and operate buildings. Humanity is paving and enclosing the earth at an unthinkable rate. According to the International Energy Agency, an estimated 2.6 trillion square feet of new floor area will be added to global building stock between 2020 and 2060—the equivalent of throwing up a New York City every month.”

• • •

All narratives are simplifications, though some work harder than others. Reagan’s version of “freedom” has morphed into a pop-culture aesthetic that combines vulgar Americana, the fetishization of the military and guns, and an Originalist mindset. The word is so predictably reactionary that the term “muh freedoms” became a light industry of social media pages, memes, and beer.

But is it any more easily parodied than the young woman on a Socialism conference panel who held up a leftist flyer and demanded to know if anyone had asked the tree if it wanted to be made into that piece of paper and get printed on?

Both left and right are idealisms of personal integrity. That is, both their political interests are for cohesion of self in the cold water of the world. In an odd turn, the party that swaddles itself in Christian teleology favors an Old Testament law of the bush and the Darwinism of the free market, while the one portrayed as godless claims to favor values laid out in the Sermon on the Mount. One rests on profit by (almost) any means, the other on the common good, whether people want it or not. Who gets to police the idealisms is the prize.

Maybe we can never choose a common narrative because all freedom is freedom from fear, and there will always be plenty of that to go around, even in the land of the free.