“First we’ll use Spahn, then we’ll use Sain

Then an off day, followed by rain

Back will come Spahn, followed by Sain,

And followed, we hope, by two days of rain.”

—Boston reporter Gerald Hern’s little poem about the two pitching aces of the 1948 pennant-winning Boston Braves, Warren Spahn and Johnny Sain

“Life’s funny, huh? I used to think that rhyme was silly. But I guess it’s how I will be remembered.”

—Warren Spahn on Hern’s famous poem

- Men at Work

I was fortunate enough to see in person three of the greatest left-handed pitchers of the post-World War II era, all in the baseball Hall of Fame, perform their craft in Philadelphia: my grandfather took me to see Warren Spahn of the Milwaukee Braves pitch against the Phillies at Connie Mack Stadium (my grandfather always called Shibe Park) in 1962 and Sandy Koufax of the Los Angeles Dodgers pitch against the Phillies in 1964. I took my grandfather to see Steve Carlton pitch for the Phillies in 1976 at Veterans Stadium. Between 1961 and 1966, Koufax was perhaps the greatest pitcher in the history of baseball, winning three Cy Young Awards (for best pitcher of the year) at a time when the award was given to the best pitcher in Major League Baseball that particular year, not the best pitcher in each league. (Giving the award to the best pitcher in each league started in 1967. The award itself was launched in 1956, one year after Young, baseball winningest pitcher died.) Between 1963 and 1966, Koufax won a total of 97 games and lost only 27, an astonishing, incomprehensible accomplishment. His collective earned run average during these years was under 2 runs per game. In three of these years he pitched well over 300 innings, mostly he completed so many of the games that he started and because he pitched in four-man rotations. No pitcher today will come close to ever doing something like this because so few starting pitchers ever finish a game and it is common to pitch in five- and sometimes six-man rotations now. (Neither Clayton Kershaw, the great lefthander of the Los Angeles Dodgers nor Max Scherzer, power-throwing righthander of the Washington Nationals, both of whom have won three Cy Youngs apiece, have never thrown as many as 250 innings in a season. The most Kershaw has thrown is 236 innings; Scherzer 228 innings. How times have changed!) Carlton pitched for 24 years and won 20 games in a season six times, although the last four years of his career were negligible as he did not even win 10 games in a season during this span. “Lefty,” as he was called by Philadelphia sportswriters, was sensational in 1972 when he won 27 games for a Philadelphia that finished in last place with only 59 wins. Carlton singlehandedly won nearly half their games, pitching 346 innings and completing 30 games with an ERA of 1.97. No pitcher today will duplicate that season.

In 1962, the year I saw him at Connie Mack Stadium, Spahn at the age of 41, won 18 games, completed 22, and threw 269 innings. And this was something of an off-year for him!

But of the great pitchers I saw while actually sitting in a major league baseball stadium, Warren Spahn was in a class by himself. In 1962, the year I saw him at Connie Mack Stadium, Spahn at the age of 41, won 18 games, completed 22, and threw 269 innings. And this was something of an off-year for him! I was thrilled that my grandfather was going to take me to see him pitch against the Phillies. I liked the Milwaukee Braves a lot, anyway. My favorite hitter was Henry Aaron and I liked the Braves’ uniforms with the tomahawk and yelling Indian warrior great deal. (I thought “Phillies” was a lame nickname for a baseball team. What the heck did that symbolize? How did being a “Phillie” put fear in the hearts of your opponents?) And now I was going to the ballpark, always a thrill, to see the great Spahn himself, after hearing about him from the old men like my grandfather. Going to see Spahn pitch was one of the most memorable days of my boyhood.

- Spahn and the Battle of Timing

“In my opinion, there has never been a better pitcher in the history of baseball than Warren Spahn.”

—Branch Rickey, 1964 (281)

Like the St. Louis Cardinals’ Stan Musical, Spahn was not a controversial player, nor charismatic. He was never dramatic; he demonstrated a manic, driving consistency in his work. He simply plied his trade with the determination that he was going to do better than most men did: in the early days working very hard at getting better, taking advice from anyone he thought had anything useful to offer, particularly hitters; and in his later years working hard at not losing his edge. Even in his youth, when he had a good fastball, he was never really a power pitcher in the way that Roger Clemens or Randy Johnson or Nolan Ryan were, although he did lead the National League in strikeouts from 1949 through 1952. (The number of strikeouts he recorded during those years were modest compared to the number of innings he pitched. He never struck out 200 batters in a year, even though he was pitching nearly 300 innings a year.) But as he grew older and his fastball, such as it was, became slower, he knew he would have to outthink opposing batters if he was to survive. He adopted new pitches, re-styled the older ones of his repertoire. He did, contrarily, what many great performers do: he reinvented himself without fundamentally changing himself because he was never confused about who he was and how he did what he did.

He won 20 or more games 13 times, an unimaginable feat; and he won more games than any other left-hander, 363. He won 23 games and lost only seven when he was 42 years old in 1963, his last great year, when, among other feats, he pitched 16 innings in a scoreless duel against San Francisco Giants ace Juan Marichal, who refused to be relieved as long as the “old man” stayed in the game. (There is a book about this game: The Greatest Game Ever Pitched: Juan Marichal, Warren Spahn, and the Pitching Duel of the Century by Jim Kaplan [2011]) No wonder he thought he could pitch for another few years but he could not. He won 6 and lost 13 in 1964 with a horrendous 5.29 ERA. Like a successful but aging boxer, he went into the ring and suddenly became very old, very quickly. He understood what was wrong; he even knew how to fix it. But he was too old for it to matter to anyone to see if he actually could.

What is most striking about Spahn was that he understood the complex, dangerous simplicity of his craft better than many: “When a pitcher faces a batter, it’s his timing against yours. Throw him the same thing every time and he’ll soon get set for it. Every good pitcher has a pitch which he likes and controls better than any other, but he also has variety. Even the fastball pitchers do. He must have it or he loses the battle of timing.” (110) It is hard for many casual fans of baseball to understand that the pitcher’s job is not to overwhelm or completely dominate a hitter but simply to disable the hitter from being able to time the pitch so that he cannot hit it well. The pitcher and the batter is like the bull and matador, (bullfighting is also a timing game), except batters get more than one crack at the pitchers; experienced bulls in sense of having been in other bullfights (bulls are, indeed, trained and bred for the ring) are never used against matadors, if they are lucky enough to survive. You can fool them only once with the movement of the muleta. Pitchers have to learn how to fool batters over and over again. Spahn did this better and longer than most. And I guess people are easier to fool than bulls.

What is most striking about Spahn was that he understood the complex, dangerous simplicity of his craft better than many: “When a pitcher faces a batter, it’s his timing against yours. Throw him the same thing every time and he’ll soon get set for it. Every good pitcher has a pitch which he likes and controls better than any other, but he also has variety. Even the fastball pitchers do. He must have it or he loses the battle of timing.”

Because he played nearly his entire 21-year career with the Braves, and most of those years when the team was in Milwaukee, although he had established himself as a star pitcher while the team was still in Boston, he did not get the press coverage and national acclaim that he might have had he played for a more storied team like the Boston Red Sox, the New York Yankees, or the Brooklyn Dodgers. East Coast sportswriters denigrated Milwaukee as Bushville. It was just a minor-league town to them.

As was the case with many players, he lost three years of his career (1943 through 1945) to military service. He was something of a war hero having fought in the Battle of the Bulge and becoming a battlefield lieutenant which he did not seem to want. Would Spahn had won 400 games if he had not lost the three years? Who can say? Even Spahn himself was unsure. Not pitching those three years may have preserved his arm or improved his maturity and made it possible for him to be successful. After being in combat, playing baseball must have seemed a lot easier and did not require that much “guts.” His first major league manager dismissed Spahn as youngster for lacking “guts.” (It should be noted that Spahn, in some respects, was a notably immature man, especially with his practical jokes, such as those he pulled Braves traveling secretary Donald Davidson who was only 4 feet tall and weighed 85 pounds and whose size seemed to struck Spahn and some of his teammates as humorous. He, pitchers Bob Buhl and Lew Burdette, and third baseman Eddie Mathews were the frat boys of the Braves. Hank Aaron—not the first black player on the team but the team’s first black star—did not especially like Spahn but both men understood that they needed each other on the field if the team was to succeed. [265])

Pitchers have to learn how to fool batters over and over again. Spahn did this better and longer than most. And I guess people are easier to fool than bulls.

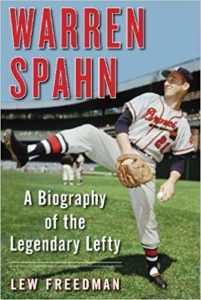

Lew Freedman’s biography of Spahn is serviceable but little more than that. The basic facts are here from Spahn’s upbringing in Buffalo to his last year in baseball with the New York Mets and San Francisco Giants, as well as some useful quotes but there are two problems with the book which, in a contradictory way, are related: Warren Spahn, at times, it seems to lose its way and Spahn ceases to be the subject of the book, for instance, in the chapters about Braves moving from Boston to Milwaukee or to the chapter on Henry Aaron or the pennant drives of 1956, 1957, and 1958; these subjects are important but in a biography of Spahn, they ought largely to be viewed from Spahn’s perspective or at least Spahn’s perspective deserves a bit more focus to give the book a greater sense of being a biography and not a history of the Braves. (There are three excellent books on the Braves’ 1953 move to Milwaukee and their 1966 move to Atlanta, moves that had an enormous impact on baseball as a business: Home of the Braves: The Battle for Baseball in Milwaukee by Patrick W. Steele [2018]and Bushville Wins: The Wild Saga of the 1957 Milwaukee Braves and the Screwballs, Sluggers, and Beer Swiggers Who Canned the New York Yankees and Changed Baseball by John Klima [2012] and Sad Riddance: The Milwaukee Braves’ 1965 Season Amid a Sport and a World in Turmoil by Chuck Hildebrand [2016]).

The second problem is that the book is not a “Life and Times” effort because it simply does not dig deep enough into the context of Spahn’s time, his socio-economic identity, the history of the business of baseball to make the book a grand historical statement. In this way, the book winds up being neither fish nor fowl as a biography: not a deep interior dive or a grand epic sweep. But if you are a true baseball fan, the book is good enough, until the real thing comes along.