Saigon Syndrome

Charting the national psyche through our nation's most controversial war.

September 29, 2015

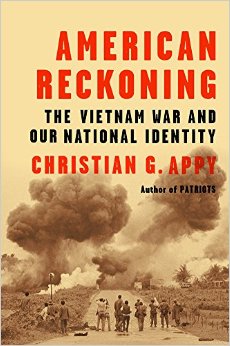

American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity

Last Days in Vietnam, the PBS documentary commemorating the fortieth anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War, was an episode in the much watched American Experience program series. As such, the two-hour synchronized production paid special attention to the part played by United States diplomatic and military personnel in the frenzied, chaotic evacuation of the few Americans remaining in South Vietnam and Vietnamese with ties to their American patrons and to the collapsing regime Washington had created, financed and armed for twenty years. The unsuccessful war against the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong) and its North Vietnamese supporters had cost the lives of more than three million Vietnamese and 58,159 Americans and displaced 5.3 million South Vietnamese from their homes. Five million tons of bombs had been dropped on the country (most of them in South Vietnam) by the United States Air Force, more than the tonnage of aerial explosives detonated by all the belligerent powers during the Second World War. The war had also generated the most intense political division in the United States since the Civil War, its outcome the only defeat in the nation’s crowded history of wars.

Graham A. Martin, the U.S. Ambassador to South Vietnam at the time (and among the last Americans to depart Saigon), blamed defeat on congressional termination of military assistance to the discredited South Vietnamese government of President Nguyen Van Thieu. Other American officials criticized Martin for his misleading optimistic reports to Washington about the rapidly deteriorating status of South Vietnamese military forces and for failing to implement contingency plans for an orderly withdrawal from Saigon.

The portrayal of Last Days in Vietnam as a tragedy, which it surely was, nonetheless reinforced the narrative and memory of the war in the United States as a validating American experience. Television viewers were invited to perceive the rescue of Vietnamese refugees fleeing from the victorious communists onto already over-loaded helicopters and packed, leaky boats ferried to U.S. naval vessels in the South China Sea as heroic, benevolent and virtuous acts, reclaiming America’s moral authority on behalf of a noble cause. [[i]] There is no attention in the video production to the causes of American involvement in Vietnam, its conduct in the war or the reasons for its defeat. Those questions have been left to historians who continue to debate the issues of the conflict and to politicians who, as recently as the 2015 pre-presidential primary season, have resurrected the war as fair game for their views about heroic identity.

Over time, however, as the war’s time-line has receded, more attention has been given to the consequences of the conflict and how it has been folded into American historical consciousness. A recent example of this genre is Patrick Hagopian’s study, The Vietnam War in American Memory (2009), which examines how construction of Vietnam war memorials in the United States (he counts at least 461 of them) became the stage on which contrasting memories about the war and its legacies have continued to compete. In particular, Hagopian discusses the acrimonious debate concerning the design and the contradictory interpretations of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial on the National Mall in Washington. He effectively explains how the intentions of the memorial’s architects to bring closure to the personal and emotional scars of the war and heal political divisions created in its wake failed to do so, and were exploited to consecrate the war as patriotic sacrifice and to promote national allegiance and commitment to future conflicts. He reminds us of a similar role which military cemeteries and memorials played in reshaping the memory of World War I in Europe, a theme deftly analyzed by the late George Mosse who traced the historical roots of the “myth of fallen soldiers,” the sacred, sacrificial experiences of those who had fought and died that were mobilized by future generations for the cause of national unity, loyalty and subsequent hallowed martial participation.[ii]

In his new book, American Reckoning: The Vietnam War and Our National Identity, Christian Appy dissects how the war in Vietnam challenged the cult of “fallen soldiers” in the United States and claims that the conflict “shattered the central tenet of American national identity—the broad faith that the United States is a unique force for good in the world, superior not only in its military and economic power, but in the quality of its government and institutions, the character and morality of its people and way of life.” In this vision of national identity, America is exempt from the flawed character, motives and actions of other countries—a redeemer nation whose conduct at home and abroad is exceptional. Long regarded a vital part of the nation’s perceived birthright and privileged status, Appy contends these attributes were the proclaimed and prevailing rationale allegedly guiding America’s behavior in world affairs. In reality, he asserts, the professed ideals were not honored in practice. Unsurprisingly, he argues that the destructive and immoral actions of the United States in Vietnam punctured the myth of American exceptionalism, undermining the nation’s avowed principles and deeply wounding the trust of its citizens in their government whose deceptions, untruths, arrogance and abuse of power in the name of exclusive American virtue have sharply diminished democracy at home and freedom abroad.

Professor of history at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst and scholar of American culture and politics during the Vietnam War era, Appy is well positioned to write this book which is clearly intended for an audience beyond academics in the field. Heretofore, Appy is best known for his volume, Working Class War: American Soldiers and Vietnam (1993), at the time a pioneering documentation and analysis of the social and economic profile of the two and a half million GIs who served in Vietnam, 80 percent of whom came from working class, lower economic and mostly high school educational backgrounds. His research disclosed, in stark fashion, the inequitable, biased and unfairly administrated character of the selective service system during the war. Appy’s second book, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides (2003) reflects the shift in historiography about the conflict and its legacies by providing contextual, extensive oral reflections of how the war experience has been remembered in both the United States and Vietnam by those who fought, supported or opposed the war.

The myth of “fallen soldiers” has continued to fray, Appy asserts, in the wake of United States interventions since the end of the war in Vietnam, particularly in the 21st century, even as every president has continued to repeat the mantra of American exceptionalism as the guiding light of the nation’s military operations abroad.

Appy’s stated intention in his current publication is “to explore the ways the war changed our national self-perception” and resulted in the loss of faith in American exceptionalism and trust in national government leadership. This, despite extensive efforts of revisionists to recalibrate the war as a “noble cause” and those who fought in it as sacrificial heroes denied victory by the media, opponents of the war at home and even by civilian foreign policy makers. The myth of “fallen soldiers” has continued to fray, Appy asserts, in the wake of United States interventions since the end of the war in Vietnam, particularly in the 21st century, even as every president has continued to repeat the mantra of American exceptionalism as the guiding light of the nation’s military operations abroad.

Appy provides an adroit discussion of how the ideology was applied to America’s lengthy tenure in Vietnam. Buoyed by its triumph in World War II and convinced that victory had validated its exceptional credentials, Americans believed they were immune from the sins of French colonialism and could be the saviors of the Vietnamese when the French were defeated by the Vietnamese in 1954. Appy describes, for example, the powerful impact of cultural icon U.S. navy doctor Tom Dooley, a St. Louis native who reconfigured his medical mission serving refugees from north Vietnam to the south in 1954 and 1955 into a romantic story in which the American rescue operation was characterized as a “holy mission,” sanctified by liberating “poor and tortured Christians from godless Communism.” Dooley’s account, Deliver Us From Evil (1956), initially appeared in condensed form in the Reader’s Digest (then the nation’s largest circulation magazine) and the book itself sold more than a million copies, assisted by the author’s appearance on radio broadcasts, television shows and self-promotion speaking tours. Coupled with a blitz of official U.S. praise and endorsements of the newly created state of South Vietnam and its president, Ngo Dinh Diem (labeled by a Life magazine article in 1957 “The Tough Miracle Man of South Vietnam” and by Vice President Lyndon Johnson in 1961 “the Winston Churchill of Asia” ), the United States portrayed its diplomatic, economic and military support of the Diem regime and the multiple governments which followed it as protecting a bulwark of democracy and freedom in Southeast Asia against the iniquities of communist aggression. American power was being used necessarily and “reluctantly … as a force for good and freedom” in Vietnam.

The truth, of course, was something else. Appy presents accumulated evidence of the distortions, lies, deliberate omissions of information, cover-ups and falsehoods by United States officials and military commanders about the nature of the government in Saigon and the fabricated justifications for America’s aggressively violent and destructive conduct of the war. He also shows how the ideological contradiction of American exceptionalism was strikingly and ironically revealed in the public reaction to the My Lai massacre, “that atrocities happen in all wars.” Yet “if all wars, and all armies produce atrocities,” Appy asks rhetorically, “how could the United States continue to regard itself as exceptionally virtuous?”[149]

Exposure of military atrocities in Vietnam (My Lai was not the only one), growing opposition to the war, especially by returning veterans, and, most of all, endless prosecution of the war without victory eroded public support for continued American engagement in the conflict. Support for the war had steadily declined beginning in mid-1967 and by early 1968 opposition had reached over 50 percent. More significantly from Appy’s perspective, by 1971, 58 percent of Americans polled “had concluded that the war in Vietnam was not just a mistake but immoral,” a view increasingly held in the two decades following the conflict. Just a third of Americans “still trusted the government to do what was right.” [iii]

Appy attributes public doubts about United States military interventions overseas to the American experience in Vietnam and he roundly condemns exponents of military global reach who maliciously continue to invoke “America’s exceptional institutions, values and resources” on behalf of military interventions abroad. He assails “[t]he tiny elite that makes U.S. foreign policy… and deploys the nation’s imperial power” for perpetuating the illusion of American innocence and good will while violating the nation’s most cherished and declared ideals by its pernicious conduct abroad.

The claim that the Vietnam War shattered the central tenet of American national identity or the Fallen Soldier myth seems diminished by the evidence. That opposition to the Vietnam conflict ended the draft and increased public resistance to prolonged quagmire wars is undeniable. It can also be argued as well, however, that the defeat in Vietnam marked the point at which a slow decline of American global power commenced and continues.

In the final chapters of the book Appy recites this verdict in narrating post-Vietnam War actions by the United States abroad, indicting every presidential administration for misdeeds in Central America (Carter, Reagan and George H.W. Bush), Asia (Ford, Carter and Reagan) and particularly the Middle East, including Afghanistan (Carter, Reagan, George H.W. Bush, Clinton, George W. Bush, and Barack Obama) while arguing that American domestic opinion, intentionally ignored or misinformed, was nonetheless apprehensive about and increasingly opposed to most of these undertakings.

But objection to protracted military engagement does not necessarily translate into rejection of American exceptionalism. Appy himself concedes the hold which such belief continues to exercise among citizens of the nation, citing a 2010 USA Today/Gallup poll in which 80 percent of those asked agreed that the United States “has a unique character that makes it the greatest country in the world” and two-thirds believe America “has special responsibility to be the leading nation in world affairs.” [334] The claim that the Vietnam War shattered the central tenet of American national identity or the Fallen Soldier myth seems diminished by the evidence. That opposition to the Vietnam conflict ended the draft and increased public resistance to prolonged quagmire wars is undeniable. It can also be argued as well, however, that the defeat in Vietnam marked the point at which a slow decline of American global power commenced and continues.

The apparition of America’s war in Vietnam thus continues to hover over the myth of American exceptionalism. Ironically, in Vietnam itself, where two-thirds of the population was born after the fall of Saigon and the reunification of the country in 1975, most of the people bear no ill will towards the United States, living in the moment and for the future. At the same time in a singular moment in Vienna, Austria on July 14, 2015, a former Vietnam veteran and prominent anti-war activist now U.S. Secretary of State, John Kerry, “recalled going off to war as a young man, the traumatic experience of Vietnam, and his commitment, when he returned, to end that war … and prevent the horrors of [future]wars.” That indeed, would be an American exceptionalism.[iv]

[i] Heather Marie Streir, “Hiding behind the Humanitarian Label: Refugees, Repatriates and the Rebuilding of America’s Benevolent Image after the Vietnam War,” Diplomatic History Vol. 39, #2, April 2015, 223-244.

[ii] Patrick Hagopian, The Vietnam War in American Memory: Veterans, Memorials and the Politics of Healing

(Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2009); George L. Mosse, Fallen Soldiers: Reshaping the Memory of the World Wars (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

[iii] “Trends in Support for the War in Vietnam, 1965-1972,” in George Herring, America’s Longest War: The United States and Vietnam, 1950-1975 ( Fourth Edition New York: McGraw-Hill, 2002), 212; Roper and Gallup Organization polls, 1975-1990 and CBS/New York Times polls which posted different results for 1985-2000 with 37 percent agreeing that the war was “wrong and immoral”, 10 percent saying it was “wrong but not immoral” and 34 percent calling the conflict “a noble cause.” The tables are reproduced in Hagopian, Vietnam War in American Memory, 13-14.

[iv] Thomas Fuller, “Memo From Vietnam: War Veterans Lead the Way in Reconciling Former Enemies,” New York Times, July 6, 2015, 4; 10; Thomas Fuller, “Memo From Vietnam: Capitalist Soul Rises as Ho Chi Minh City Sheds Its Past,” http://www.nytimes.com/2015/07/21/world/asia/ho-chi-mionh-city-finds-its-soul-in-a-voracious-capitalism-html. Accessed August 3, 2015; Robin Wright, “Letter From Iran: Teheran’s Promise,” The New Yorker (July 27, 2015), 27.