Writer Hunter S. Thompson, who died in 2005, has had a resurgence in recent years, due in part to his reputation as an avenging spirit from the anti-Nixon ‘60s and ‘70s.

A Nation article in 2016, for example, says Thompson was a prophet who “foresaw the retaliatory, right-wing politics that now goes by the name of Trumpism.” Social media sites regularly quote 50-year old passages from Thompson as commentary on our time, and newspapers long for him to condemn everything wrong with American politics today.

In 2017 one of Thompson’s early editors, Warren Hinckle of Ramparts and Scanlan’s, published a book of collected “appreciations” of the writer, and in 2020 Thompson’s illustrator Ralph Steadman toured a Thompson-infused retrospective that was paused for the pandemic.

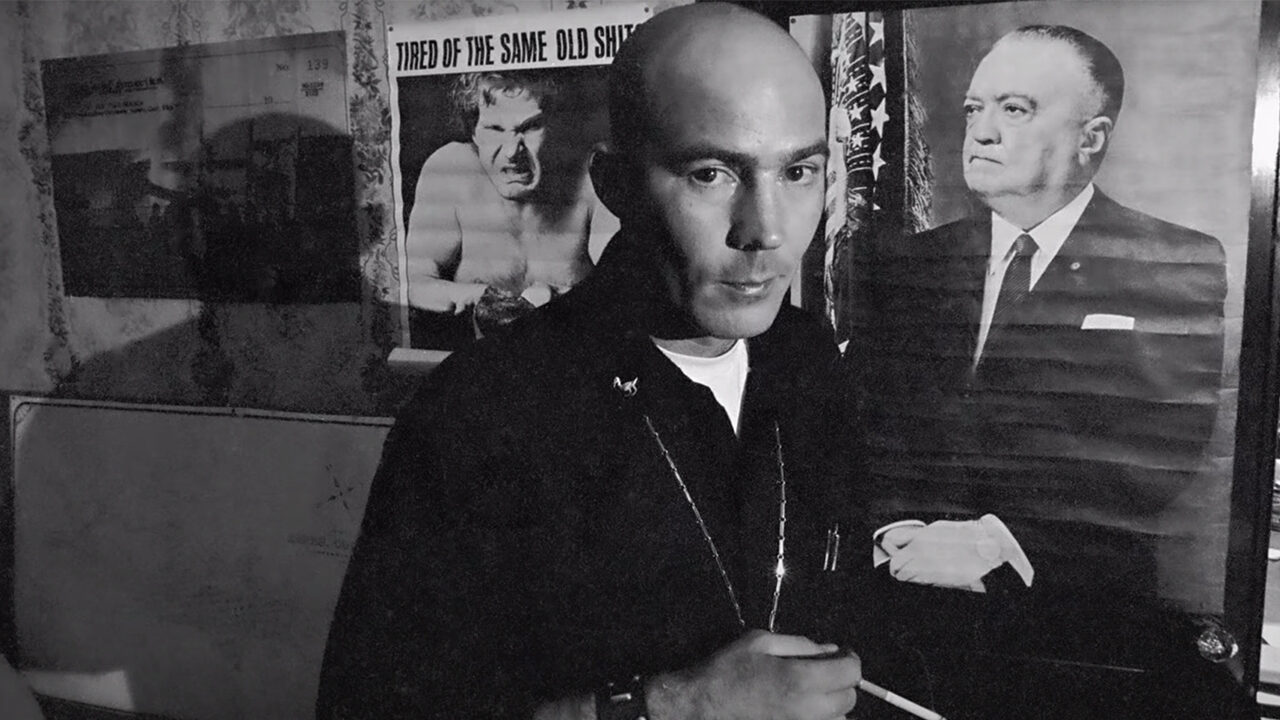

Three more Thompson-related efforts are ongoing, from writer Daniel Joseph Watkins: a new edition of his 2015 book on Thompson’s 1970 campaign for sheriff of Pitkin County, Colorado; an exhibition (on display through August 15 at Poster House in Manhattan) of artist Thomas W. Benton’s collaborations with Thompson for that campaign; and a new documentary on the campaign: Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb, co-directed by Watkins and Ajax Phillips, and produced by Mimi Polk Gitlin, whose credits include Thelma & Louise.

The film, created from old footage never seen before by the public, is streaming on Amazon, Apple, and elsewhere, and is worth a look, both for historical/fandom interest and for how it portrays earlier aspects of our current divide.

• • •

Thompson’s best writing is from the first two decades of his career, much of it political journalism. His first published book, Hell’s Angels (1967), was a participatory ethnography project that shows the bikers not as counterculture figures—that is, not as anti-establishment types somehow in league with the hippies, as some mistook them to be—but as fascistic, vengeful wing-nuts: (mostly) White men who felt left behind in a changing America, who decided they hated “communists”—the epithet that equates to “socialists” today—and who formed temporary alliances with the police against antiwar and Black activists, though they were always ready to turn on the police too. Sound familiar?

It is this writing that makes Thompson seem most prescient. “American law enforcement procedures have never been designed to control large groups of citizens in rebellion,” Thompson writes about the bike gangs, in a passage that could be about the Capitol insurrection. “More and more often the police are finding themselves in conflict with whole blocs of the citizenry, none of them criminals in the traditional sense of the word, but many as potentially dangerous—to the police—as any armed felon.”

Sonny Barger, a main character in the book and a chapter president of the Angels, is asked by a bystander about the Nazi imagery they use. “That don’t mean nothin, we buy that stuff in dime stores,” Barger says. Then, with the coyness of the alt-right, he reverses himself. “But there’s a lot about that country we admire…. They had discipline. There was nothing chickenshit about ‘em. They might not of had all the right ideas, but at least they respected their leaders and they could depend on each other.”

“American law enforcement procedures have never been designed to control large groups of citizens in rebellion,” Thompson writes about the bike gangs, in a passage that could be about the Capitol insurrection.

After Hell’s Angels, Thompson developed a reputation for being, as John Leonard says in a Times book review in 1979, someone who was “attracted to those who were outside the protection of the law or who were oppressed by that law,” including activists in the Chicano movement in East LA, Native Americans fighting for fishing rights in Washington State, and African Americans in Louisville, where he was from.

“The fear and loathing that he found in these places was not a hallucination,” Leonard says. “The rage he acquired seems inexhaustible. He became, in the late 1960’s, our point guard, our official crazy, patrolling the edge.” (The edge, like The Center, is relative.)

Douglas Brinkley, who served as editor for Fear and Loathing in America, the second volume of Thompson’s letters, says in his introduction, “But unlike other sharp-tongued critics of the American political process, there was a Jeffersonian idealism in Thompson’s writing that transcended mere cynicism.” Brinkley says George McGovern, the Democratic nominee for president in 1972, pronounced Thompson “a patriot.” Ralph Steadman says the same thing in the new documentary.

“Basically I think [Thompson] wanted to see this country live up to its ideals,” Brinkley says.

Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb is a brief portrait of a brilliant young writer, frustrated with his local and national governments, applying his beliefs to the practice of grassroots politics instead of keeping to the commentariat. For any young writers who wish to “write like Hunter S. Thompson,” or fans who love the Johnny Depp portrayal, the documentary will be instructive.

Douglas Brinkley, who served as editor for Fear and Loathing in America, the second volume of Thompson’s letters, says in his introduction, “But unlike other sharp-tongued critics of the American political process, there was a Jeffersonian idealism in Thompson’s writing that transcended mere cynicism.”

Ed Bastian, Thompson’s Campaign Manager in 1970, says in the film, “This image people have of Hunter, later, as being this mad, Gonzo journalist, was absolutely not who he was at that time. He was all business.”

• • •

After Hell’s Angels Thompson got many offers. In January 1968 he wrote his mother that he had had a “five-hour dinner with the Vice-President of Random House, the editor-in-chief of Ballantine (& my lawyer) at the Four Seasons, the most expensive restaurant in N.Y.,” about a proposed book “being referred to as ‘The Death of the American Dream’—which makes me nervous because it’s so vast & weighty.”

An early concept for that book, revealed in a letter from Thompson to the editor of The Nation, two weeks later, is that it would “kick off with a gaggle of profiles, or sketches, of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. That’s the first chapter…but after that, I’m open.”

“What I’ll really be writing, I think, is a sort of Prosecutor’s Brief, demanding a fitting penalty for the killers of the ‘American Dream,’” Thompson says. He acknowledges the vagueness of the project and the difficulty of “taking on the whole Establishment in one swack.”

Despite endless anxiety and years of problems with his publisher, he would never write the book. In a letter dated January 13, 1970, he tells his editor at Random House, “And all I can say about it, for sure, is that I want to get it written and DONE…finished, gone, off my neck and somewhere way behind me. I loathe the fucking memory of that day when I told you I’d ‘go out and write about The Death of the American Dream.’”

Yet he drifted around in the concept, using variations of the phrase “American dream” in piece after piece, still hoping to reach the end of the project, until it became just a tic.

• • •

It is hard to know what Thompson meant by “the American dream.” It was not, exactly, the bromide that each generation should do better than the one before, or be able to buy houses and put Ford Galaxies under their carports. In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream (which uses the phrase 19 times), he satirizes it with its cheapest connotations, from “that vision of the Big Winner somehow emerging from the last-minute pre-dawn chaos of a stale Vegas casino,” to “a mental joint, where all the dopers hang out.”

Certainly he was idealistic, as Brinkley says. The TV ad for his 1970 campaign stated that he was “a moralist disguised as an immoralist,” and for years he attacked corrupt politicians for failing America. But given his iconoclasm, hatred of “greedheads” and “fatbacks,” his love of guns and drugs, and frequent struggles with the IRS, one might imagine he had in mind some left-libertarian vision of what the experience of living in this country should be.

Built into that vision is absence: the freedom from. Freedom from being told how to live, freedom from others’ rapaciousness, freedom from state violence. One of the assignments he took in the name of the American Dream book was the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968, where he got caught in the violent police riot. In the strain to write what he had witnessed, his consciousness split, in a sense, and he invented a fictional alter-ego, Raoul Duke, to say things he wanted to say, such as “the American Dream was clubbing itself to death just a few feet away.” The device was important to him; Duke would become the protagonist of Fear and Loathing in 1971.

“I went to the Democratic Convention as a journalist,” Thompson wrote, “and returned a raving beast.”

The Convention was in August 1968. In January 1969 he wrote his friend Oscar Zeta Acosta, the Chicano activist and attorney, “If you had any sense, you’d steal some money and buy a ranch on the Western coast of Mexico. Get hold of a good green hillside looking down on the sea and build something on it. Make a decent human place where people can come and really feel peace—if only for a few hours, before rushing out again to that stinking TV world. […]

“Well, maybe I’m leaning too far in my own direction here, maybe trying to justify my efforts to build a personal fort where the pigs can’t get me except on my own terms…but even if I’ve overdone my thing out here, I’m convinced the instinct is valid…like Don Juan’s idea of a sitio. I think you need at least a claim on a sense of internal order before you can rush out and rip at the world.”

The TV ad for his 1970 campaign stated that he was “a moralist disguised as an immoralist,” and for years he attacked corrupt politicians for failing America. But given his iconoclasm, hatred of “greedheads” and “fatbacks,” his love of guns and drugs, and frequent struggles with the IRS, one might imagine he had in mind some left-libertarian vision of what the experience of living in this country should be.

Thompson’s personal fort was in Aspen, Colorado, where he rented in the early ’60s and bought a house in nearby Woody Creek later in the decade. Aspen was a former mining town in a secluded valley, developed as a ski resort after WWII by German, Austrian, and Swiss immigrants. By the ‘60s it was known for a mix that Thompson identified as Left/Crazies, Birchers, bigots, Nazis, psychedelic farmers, cowboys, firemen, cops, construction workers, bikers, anarchists, and shopkeepers. There were about 2,500 residents, but it had become a destination for hippies, after “things like the Haight-Ashbury didn’t work,” Thompson says in the film. Many would be looking for a fort in Nixon’s America.

Bob Braudis, a close friend of Thompson’s, and later a longtime sheriff of Pitkin County, tells me on the phone, “The town was to the right of Clorox.

“You had a lot of people from Europe who were Teutonic,” he says wryly, though “not nearly as fascist” as Thompson claimed. “They were threatened by the recently-arrived longhairs making noise, and accused them of polluting the rivers.” The film shows them smoking weed and skinny-dipping.

Guido Meyer, a police magistrate and innkeeper in town, and one of Thompson’s primary “Nazi” targets, says in dog-whistle footage in the film, “To take care of this [hippie/freak] problem, I would get businessmen who mean business, that stand up and have backbone, and will stand up as American citizens, the way American citizens were 30 years ago. Stand up for their country, for law and order.”

Police worked out on heads, hippies, and other youthful spirits with long (or short) hair, charging them with crimes from drug possession to vagrancy, loitering, or trespass, and sometimes roughing them up. As with today’s culture wars, there was also a class and anti-intellectual component.

There were about 2,500 residents, but it had become a destination for hippies, after “things like the Haight-Ashbury didn’t work,” Thompson says in the film. Many would be looking for a fort in Nixon’s America.

“In 1970, if you scratched a hippie you’d find a Jag or a Porsche,” Bob Braudis tells me. Heads were often educated young people, from money or with good jobs, who “decided to become radical liberals.” Braudis says, “You couldn’t go into a bar without having an intellectual conversation.” Braudis himself was a young analyst for Dun & Bradstreet when he dropped out and moved to Aspen to become a ski instructor.

Add to this the fact that the “burghers,” as Thompson called them, believed in what he called “land rape”—aggressive development—and Thompson and others felt they were about to lose the last best hope for their chosen lifestyle in a beautiful setting. What could be done?

“It seems to me the way to cope with power is not to ignore it but to get it,” Thompson says in the film.

His “Freak Power” coalition’s first try was to get 29-year old lawyer Joe Edwards elected Mayor of Aspen in November 1969. In his writing Thompson usually reduces Edwards to a “dope-smoking bike freak” to heighten the culture clash, but the online Aspen Hall of Fame entry for Edwards says, “In 1967, Edwards filed a civil rights case against city of Aspen officials for harassing hippies, commonly referred to as the ‘hippy trials.’ An outgrowth of this was the formation of Citizens for Community Action, a forum for community consensus which defined the image and character of Aspen and the upper Roaring Fork Valley Elements of the CCA included [sic] creating a city/county planning office, adopting a master land use plan, establishing public transportation and supporting citizen participation in long term community planning processes.”

Thompson writes in his article “Freak Power in the Rockies,” in Rolling Stone in October 1970: “The people who had reason to fear the Edwards campaign were the subdividers, ski-pimps and city-based land-developers who had come like a plague of poison roaches to buy and sell the whole valley out from under the people who still valued it as a good place to live, not just a good investment. Our program, basically, was to drive the real estate goons completely out of the valley…. With Edwards, [the old-timers and ranchers] said, would come horrors like Zoning and Ecology, which would cramp their fine Western style, the buy low, sell high ethic…free enterprise, as it were, and the few people who bothered to argue with them soon found that their nostalgic talk about ‘the good old days’ and ‘the tradition of this peaceful valley’ was only an awkward cover for their fears about ‘socialist-thinking newcomers.’” (Note that for some “free enterprise” is the American dream.)

“It seems to me the way to cope with power is not to ignore it but to get it,” Thompson says in the film.

Despite their “central problem” being “the gap that separates the Head Culture from activist politics,” as Thompson defines it, his coalition’s voter-registration efforts worked. Joe Edwards lost by only six votes, and five of those came in for him later as absentee ballots that missed the deadline. The whole thing had started as a little épater les bourgeois for the good burghers and their reactionary kin, but it got serious.

Thompson says in his article that with Edwards near-win, “The Old Guard was doomed, the liberals were terrorized and the Underground had emerged, with terrible suddenness, on a very serious power trip. Throughout the campaign I’d been promising…that if Edwards won this Mayor’s race I would run for Sheriff next year…but it never occurred to me that I would actually have to run….”

• • •

Moralists hope to change things for the better, even when they act like nihilistic immoralists. In his January 13, 1970, letter to Jim Silberman, his editor at Random House, Thompson let his mind race about aspects of the American Dream book, in part to buy some time for the now-late manuscript, which he saw as incoherent. (The panicked rant of a writer deep in a project and far past deadline should be acknowledged as a useful genre for what it reveals.)

In the process he connects his “land-fortress” downvalley from Aspen (“which Is not really my house and probably never will be”), the American Dream book, and the approaching sheriff’s election.

“I came out here hoping to live in lazy peace with the locals,” he says, “but finally—and inevitably, I think—that dream of ‘the Peaceful Valley’ went from nervous truce to nasty public warfare,” due to the Edwards campaign. “So now a lot of those people who called me a friend…now call me a communist dope-fiend motherfucker.”

He says that in 1963 “the cowboys dug me,” but, “Now, in the wake of this new polarization [and near-success of the Freak Power campaign]…many locals…tell each other—in the course of their steady tavern-talk—that the valley would be a lot better off if somebody broke both my legs and dragged me back to Haight street behind a pickup truck.”

“And that’s really what I’m trying to write about,” he says. “As it sits now—in this heap of terrible garbage on my desk—the A[merican] D[ream] ms. begins on election night in 1969, with a quick recap of Joe Edwards’ mayoral campaign and me sitting on the floor in headquarters, completely burned out after three weeks of sleepless work, wondering what kind of madness had caused me to be there. […]

“[F]inally I traced it back to that night in September, 1960, when I quit my expatriate-hitchhiker’s role long enough to…watch the first Kennedy-Nixon debate on TV…. That was when I first understood that the world of Ike and Nixon was vulnerable…and that Nixon, along with all the rotting bullshit he stood for, might conceivably be beaten. I was 21 then, and it had never occurred to me that politics in America had anything to do with human beings. […]

“My central ambition, in the fall of 1960, was to somehow get enough money to get out of this country for as long as possible…. Just get out, flee, abandon this crippled, half-sunk ship that A. Lincoln had once called ‘The last, best hope of earth.’

“In October of 1960 that phrase suddenly made sense to me. I’m not sure why. It wasn’t Kennedy. He was unimpressive. His magic was in the challenge & the wild chance that he might even pull it off. With Nixon as the only alternative, Kennedy was beautiful—whatever he was. [H]e hinted at a chance for a new world—a whole new scale of priorities, from the top down.”

Moralists hope to change things for the better, even when they act like nihilistic immoralists. In his January 13, 1970, letter to Jim Silberman, his editor at Random House, Thompson let his mind race about aspects of the American Dream book, in part to buy some time for the now-late manuscript, which he saw as incoherent.

The talk of the unworkable “AD book” would be converted for use in the more contextually-specific Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas.

“You could strike sparks anywhere,” he wrote in the 1971 Rolling Stone version of Fear and Loathing. “There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning.…

“And that, I think, was the handle–that sense of inevitable victory over the forces of Old and Evil. Not in any mean or military sense; we didn’t need that. Our energy would simply prevail. There was no point in fighting–on our side or theirs. We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave.”

Of course, what happened between his vision of Kennedy in 1960 and his 1970 sheriff’s campaign was everything: Vietnam, Civil Rights actions, the hippie movement, the assassination of our political leaders, and what Thompson called “the [1969] Summer of Hate.” By the time of Fear and Loathing he famously says that with “the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high water mark–that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back.”

But the Freak Power campaigns were like one last responsible stand, “‘…to try to enact a whole new style of politics in Aspen,” as Thompson says in the film. “We’ve come to a point with the nation completely shattered, and we’re heading for…chaos and rubble, or maybe the end, unless we can figure out some way to live in a peaceful, tolerant situation, where people who don’t agree with each other can live.”

“Freak Power was the collective energy of a mass of people, for the first time in my life, trying to take control of our political environment,” says Bob Braudis in the film.

Ed Bastian, the Freak Power Campaign Manager, says in his deep, grave voice, in 1970, “We’ve got a potential of a revolution in this country, unless we can make this kind of democracy work. Unless the vote can work, we’re gonna have bombs.”

“Freak Power was the collective energy of a mass of people, for the first time in my life, trying to take control of our political environment,” says Bob Braudis in the film.

Thompson reminds Silberman at the start of that year that “Fitzgerald wanted to call his book about Gatsby ‘The Death of the Red White and Blue.’” Any hope Thompson might have had for his own book seems gone.

“As it is, I feel like some kind of pompous old asshole writing his memoirs. I feel about 90 years old. […] Fuck the American Dream. It was always a lie & whoever still believes it deserves whatever they get—and they will.”

A few months later, as the film shows, Thompson says to his supporters, “It’s a weird irony I would have to run for sheriff, of all fucking people.”

• • •

Freak Power: The Ballot or the Bomb is based on Daniel Watkins’ book, but the documentary was made possible when Aspen artist Travis Fulton found a canister of 16mm film, shot by his brother, Robert Fulton III, in his barn and realized it was from Thompson’s campaign. Robert Fulton’s daughter, Florence Fulton Miller, manages his estate. At a “serendipitous meeting” in the Woody Creek Tavern, where Thompson used to drink, Watkins was introduced to Flo Miller by Bob Braudis.

(To illustrate the connections in the small community, Watkins laughs and tells me that Braudis’ second marriage was to Travis Fulton’s ex-wife, so Flo Miller was akin to Braudis’ niece. Watkins has been friends with Bob Braudis for 10 years.)

Searches of Fulton archives in Aspen, Los Angeles, and Connecticut uncovered a total of forty reels of film, eight hours total, from the campaign. All had to be digitized; some had never been developed. Some film had sound; other film did not, or was recorded as sound only. Watkins had to log descriptions of all the footage, and transcriptions of people talking, just to match sound and images. He also gathered 3,000 still images by photographers David Hiser and Bob Kreuger.

Gitlin explains to me that she knew Thompson from days at the Chateau Marmont, the LA hotel where the Johnny Depp Fear and Loathing was rehearsed. She likes best that the documentary shows him in his time as a serious journalist, but that he was also “playful and provocative, which drew you more to him.”

Daniel Watkins and Travis Fulton made a “primitive version” of the documentary in a little cabin next to the barn, Watkins tells me on the phone, then “took it to Hollywood.” A mutual friend in Aspen introduced him to producer Mimi Polk Gitlin, who was able to bring the project together with financing, editing, mixing, and music (including an original song with lyrics by Paul Williams and music by Gary Clark Jr. and Gustavo Santaolalla).

Gitlin explains to me that she knew Thompson from days at the Chateau Marmont, the LA hotel where the Johnny Depp Fear and Loathing was rehearsed. She likes best that the documentary shows him in his time as a serious journalist, but that he was also “playful and provocative, which drew you more to him.” He spoke truth to power, she says, in a way that is both accessible and relevant today, especially since more young people are setting out to change politics and have high priorities for voting rights, de-escalating policing, and protecting the environment.

“Trump is a real-estate developer,” she reminds me.

• • •

The documentary limits itself mostly to Fulton’s contemporary footage, and there are times I wish I could hear more specific things. It is possible to see, however, that “the American dream” meant to Thompson, in this one case, equal justice, participatory democracy, a livable community, and a government that reflects the will of the people.

His platform had six planks: 1) Prohibit cars from downtown and sod the streets; 2) Rename Aspen “Fat City” to make it distasteful to investors and developers; 3) Control street drug sales (mostly by preventing profits); 4) Forbid hunting and fishing to non-residents; 5) Disarm the sheriff and deputies in public; and 6) “savagely…harass all those engaged in any form of land-rape.”

Thompson uses a flow chart to show that in his plan the sheriff would serve as ombudsman for the people, and his office would have a Consumer Action Bureau, Public Information Unit, and Volunteer Service Corps; an “undersheriff” would do what remained of traditional enforcement, such as serving summons, traffic duty, investigation, rescue, etc.

Having police heavily armed in public, he stresses, creates “psychic violence, [which] is part of this polarization we’re seeing all over the country.”

It is possible to see, however, that “the American dream” meant to Thompson, in this one case, equal justice, participatory democracy, a livable community, and a government that reflects the will of the people.

(I wonder about the unacknowledged influence of Oscar Acosta on Thompson’s campaign. Acosta is often seen in the background in the film and photos; a photo in the new Acosta biopic shows him, Thompson, and Ed Bastian deep in conversation. Acosta had recently run on the Raza Unida Party ticket for Sheriff of Los Angeles County, in reaction to police brutality against the Chicano community. Thompson gives him a single sentence in “Freak Power in the Rockies,” acknowledging Acosta got more than 100,000 votes. The first plank of Acosta’s platform was “The ultimate dissolution of the Sheriff’s Department.”)

Thompson says of his platform in general, “I think if it worked here, it could work in a lot of smaller communities. The point about, ‘People say if Thompson is elected, caravans of drug addicts are gonna leave Boston at once and come across the country, beating gongs’…the whole point is we should make it work here and tell those fuckers to stay where they are and make it work there, and not to come here.”

The “Aspen technique,” of “calling [the system’s] bluff,” as Thompson says in “Freak Power,” was intended to serve as a model for people to get things right locally then, maybe, somehow, grow them to the national level.

Incumbent Sheriff Carrol Whitmire, whom the Aspen Times says had a ninth-grade education, faced a “torrent” of “sophisticated” media stunts, including Tom Benton’s art for the Aspen Wall Posters; a fake radio personality named Bill Greed the land developer; Ralph Steadman ads that said of Whitmire, “Vote before he shoots”; and a rigged debate between Whitmire and Thompson, who was both deadly earnest and funny. It would be like a commedia dell’arte troop putting on a continuous show to get themselves elected in your town.

“Scores” of young people wanted to be involved in Thompson’s campaign, which scared those in power. They had told the new generation to become part of the system, if they wanted change—but not like that. Dwight Shellman, a Freak Power lawyer, says in the film that the establishment would “call people in, develop ambiguity about what precinct the person lived in, and then proceed…to thrust the burden [of proof] on the voter…. And I think that is exceedingly undemocratic and exceedingly unlawful.” All challenges to voting were dismissed but one—a prisoner whom a deputy took to register illegally, to vote for Carrol Whitmire.

An older local man says on camera there will be “murders” if Thompson wins. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation tells Thompson there have been six credible threats to his life and advises him to get out of the race.

In the end, he loses and admits wryly that they were so busy registering freaks in town they forgot about the rest of the county, which was conservative. A young woman sobs in the crowd at his concession. He is shaved bald, wears a frosted wig, and has an American flag draped around his shoulders. His thank-you to supporters is sober and sincere.

An older local man says on camera there will be “murders” if Thompson wins. The Colorado Bureau of Investigation tells Thompson there have been six credible threats to his life and advises him to get out of the race.

“I proved what I set out to prove,” he says. “It was more of a political point than a local election. And I think the original reason was to prove it to myself that the American dream really is fucked. Well, I didn’t believe it until now, and I’m not sure this is really the proof of it […] We made a mistake in thinking the town was ready for an honest political campaign.”

The pronouncement of the death of the American dream was preloaded in his brain, we know now, but here it seems to represent a specific, applied concept instead of anything and everything. This moment in the film feels like a true turning point between hope and cynicism, and it is possible to imagine that here he begins to become the personality that would eventually cripple his writing and destroy his health.

Ed Bastian says in the film, “After the election I think Hunter was…I think it’s probably too strong to say devastated, but it was close to that. He poured his heart and his soul and his energy into this. He did everything he could.”

Eight years later in a BBC documentary Thompson says, “The third president, Thomas Jefferson, had a vision of America. He believed that this whole new country, this giant unformed continent, offered a chance to start again. The premise was very simple. That human beings acting in a sense of enlightened self-interest are smart enough to do the right thing and know the truth. America could have been a fantastic monument to all the best instincts of the human race. Instead, we just moved in here and destroyed the place from coast to coast like killer snails. […] I think we’re finished.”

• • •

Thompson’s campaign model did not win elections and did not export. It is not as if Stacey Abrams and her colleagues won Georgia using techniques he originated. That the documentary exists to show Thompson as this other thing proves the campaign was largely forgotten by the rest of the country.

As for the campaign’s effects in Aspen, former Sheriff Bob Braudis tells me, “We won [the development] battle, but it was a double-edged sword. […] We stopped all the major land-grabs, but anything existing appreciated enormously.”

Now Aspen is called “America’s most expensive ski town,” with some of the most expensive real estate in the country. “There are 71 billionaires who live here now,” Braudis says. “There is no reason in my mind for billionaires.” He says the town imports 70 percent of its labor, “workers who live 40, 50, 70 miles away, because they can afford that,” which causes a traffic jam twice a day. Suicide rates are extremely high.

“We did mall two of the most populous streets in Aspen,” Braudis says, which created a pedestrian space, but parking is expensive and booked, with aggressive enforcement. “We surrendered to the automobile,” he says.

Hunting and fishing are still a “big source of tourist revenues,” he says.

Thompson’s campaign model did not win elections and did not export. It is not as if Stacey Abrams and her colleagues won Georgia using techniques he originated. That the documentary exists to show Thompson as this other thing proves the campaign was largely forgotten by the rest of the country.

Braudis says of his peer group: “Lots of my friends have croaked.” The head culture is gone, and “the intellectual quality of town has diminished.” But he says the Sheriff’s Office is “soft on drug enforcement still. The law is black-and-white, but as Sheriff I got to decide which laws got priority. I put it at the bottom of the list.

“Back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, big smugglers had homes in Aspen, international profiteers in the black market. Now one block in St. Louis has more demand than in Aspen. Micro-dosing acid is popular with successful 40- and 50-year olds, who can pay for their own chemists. Younger kids try Ecstasy. There are seven or eight weed stores in Aspen.”

He stresses, “There are really good people in office now, whose practices are a continuation of Hunter’s ideas. It’s still the greatest place in the world to live.”

As Ed Bastian says in the film, “In retrospect, we can see it was a really powerful oar stroke forward for the change and the political dynamics in the valley around Aspen. All the things we did: getting out the vote, the kind of tactics that we used, they all set the stage for what was to soon follow.”

The two Freak Power lawyers, Joe Edwards and Dwight Shellman, were soon elected Pitkin County Commissioners. Edwards says in the film that they developed a “more relaxed, friendly, community-service oriented type policing,” and there has been “peace in the valley for the last 30, 40 years.”

Sheriff Carrol Whitmire “left office on Aug. 9, 1976, midway through his third four-year term, under political pressure from a three-week investigation by then-District Attorney Frank Tucker. The investigation reportedly revealed mismanagement, sloppiness and lack of leadership, according to The Aspen Times archives.”

He was followed by Dick Keinast, who was to be Thompson’ undersheriff. His less confrontational approach earned the Pitkin County department the nickname “Dick Dove and the Deputies of Love.” One of those deputies was Bob Braudis, who is not even a figure in the old footage in the documentary because he was just a young guy helping on the campaign.

Braudis served as Sheriff from 1986 to 2010, became good friends with Thompson, and tells me he incorporated Thompson’s policing policies, after seeing firsthand “inhuman, unconstitutional” detainment under Whitmire. “When I was a baby deputy I saw two Aspen Police officers punch a handcuffed detainee,” he says.

“Back in the ‘70s and ‘80s, big smugglers had homes in Aspen, international profiteers in the black market. Now one block in St. Louis has more demand than in Aspen. Micro-dosing acid is popular with successful 40- and 50-year olds, who can pay for their own chemists. Younger kids try Ecstasy. There are seven or eight weed stores in Aspen,” [says Bob Braudis, Aspen sheriff from 1986 to 2010].

As a law enforcement professional, he says, “You have to push that pendulum to the natural angle of repose every day to reflect your ethics.” He offered his deputies the option of not carrying guns; all but one carried.

“We live in a gun culture,” Braudis says. “There is a very low incidence of violent crime in Pitkin County, but when it happens, it’s scary. City police carry tasers and guns.”

He agrees “100-percent” with social-worker style interventions in place of some law enforcement. “Aspen, Colorado, is the most overpoliced community in the country, with almost no crime. Putting some of that money into social workers instead of four on-duty police makes a lot of sense. One way or the other it’s going to happen.”

“Hunter was often my North Star,” he tells me. “He predicted things that actually occurred. We might have thought he was hallucinating; he was right on.”

• • •

Aspen, Colorado, gave Hunter S. Thompson a place to “hunker down,” another of his favorite phrases. When his stories become inconclusive, or about failing to find the story at all, his writing persona too “hunkers down” in the lull before apocalypse, in the “fortified compound,” as he called Owl Creek Farm; in the “City of Refuge,” on the Kona coast of Hawaii, after failing to cover the Honolulu Marathon; in the Lan Xang Hotel, in Vientiane, Laos, after failing to get the story of the fall of Saigon; or in the hotel pool in Kinshasa, after failing to dry off and go see Ali take it back in the biggest fight in the world.

Colorado is where Raoul Duke flees at the end of Fear and Loathing. It was worth fighting for, which Thompson seemed to sense instinctively.

It admitted defeat, but in those places he could let the drugs or whiskey kick in and collect his thoughts in anticipation of writing it, for better or for worse. Colorado is where Raoul Duke flees at the end of Fear and Loathing. It was worth fighting for, which Thompson seemed to sense instinctively.

This may have been his most personal version of the American dream, and it was as conflicted as most things he did. For someone who intended to be obnoxiously individual, he needed domesticity and community, in order to “rush out and rip at the world.”

• • •

I was reading around in my tattered paperback of Thompson’s collection The Great Shark Hunt, which contains “Freak Power in the Rockies,” and stumbled again on “What Lured Hemingway to Ketchum?”, from the National Observer, May 25, 1964.

Thompson admired Hemingway and was similar: he wrote both journalism and fiction, drank too much, was involved with many women, liked horse-assery, loved guns and killing things, and was progressive (or more) in politics. Both men were Romantics and sensitives posing as brutes. Both had long periods of decline ending with fatal self-inflicted wounds.

For someone who intended to be obnoxiously individual, he needed domesticity and community, in order to “rush out and rip at the world.”

“When news of his death made headlines in 1961 there must have been other people besides myself who were not as surprised by the suicide as by the fact that the story was date-lined Ketchum, Idaho,” Thompson writes. “What was he doing living there? […] The newspapers never answered those questions—not for me, at any rate…. Anybody who considers himself a writer or even a serious reader cannot help but wonder just what it was about this outback little Idaho village that struck such a responsive chord in America’s most famous writer.”

Near the end of the little essay, written about the time he moved to Aspen and before he was Gonzo, Thompson says, “Standing on a corner in the middle of Ketchum it is easy to see the connection Hemingway must have made between this place and those he had known in the good years. Aside from the brute beauty of the mountains, he must have recognized an atavistic distinctness in the people that piqued his sense of dramatic possibilities. […] From such a vantage point a man tends to feel it is not so difficult, after all, to see the world clear and as a whole. Like many another writer, Hemingway did his best work when he felt he was standing on something solid—like an Idaho mountainside, or a sense of conviction.”