1. The Way Some Prizefighters Lose

Keep your hands up, your chin down, and your ass off the floor.

—Welterweight and Middleweight Boxing Legend Sugar Ray Robinson’s Rules for Success in Boxing

By 1985, Rocky Marciano had been dead for sixteen years, the victim of a private plane crash in which a shaft of metal pierced his brain. But in the late summer of that year, everyone in the boxing world was talking about the former heavyweight champion whose last professional fight was 30 years earlier. The current heavyweight champ, Larry Holmes, was scheduled to fight the current light heavyweight champ, former St. Louisan Michael Spinks, in September in Las Vegas, Nevada, at the time the big fight capital of the world. (In the standard eight weight classifications for boxing, a light heavyweight could weigh from 160 to 175 pounds and a heavyweight weighed over 175 pounds. In the now seventeen weight classifications for boxing, light-heavyweight is 168 to 175 pounds and is called junior cruiserweight.) As a rule in boxing, at least before the sport became the quaintly deranged irrelevancy that it now is, light heavyweight champions did not beat heavyweight champions: Archie Moore, the Old Mongoose, tried to twice, against Marciano and then Floyd Patterson, and lost both times; Bob Foster, a hard puncher if there ever was one, tried against Joe Frazier and was battered into submission in two rounds for his trouble; (Foster would later lose to Muhammad Ali but that was not a title fight); Billy Conn almost pulled it off the first time he fought Joe Louis in 1941. But as the Brown Bomber famously said, “You can run, but you can’t hide.” He knocked out Conn in the 13th round. In 1939, Louis knocked out John Henry Lewis in one round in the first attempt by a light heavyweight champion to win the heavyweight title. In boxing, the iron theorem is that a good smaller fighter can never beat a good fighter who is bigger. A good light heavyweight does not beat a good heavyweight, period. When Spinks, a first-rate if rather awkward fighter, was scheduled to fight Holmes in September 1985, he was a 5-to-1 underdog, not at all likely to challenge the iron theorem. He had to go on a strict diet and body-building regimen to get his competitive weight over 200 pounds, a bare minimum to be a legitimate heavyweight in the 1980s. Marciano never fought over 200 pounds for his entire championship reign. His usual fighting weight was 185 to 190 pounds. If Marciano had been fighting Holmes that night, he would have been outweighed by 25 or so pounds. (Holmes came into the Spinks fight weight 221 pounds.) And Marciano would have been five inches shorter. It would have been like a heavyweight fighting a light heavyweight. As things turned out, this fight was as if Holmes was fighting Marciano. Probably the public would not have paid a great deal of attention to the Holmes-Spinks bout at all except for one thing. Holmes, at this point, had won 48 straight fights in his career without a loss. Enter the ghost of Rocky Marciano.

Marciano is the only heavyweight champion to retire undefeated, having won 49 straight fights. If Holmes defeated Spinks, and the odds and history greatly favored him to do so, he would tie Marciano’s record. There were many people both in and outside boxing circles who did not want Holmes to do that. Marciano had a legion of fans; he was the last great white champion. Holmes seemed like a gate-crasher to some. “ … Marciano’s family, his brother Peter, who owned a sporting goods store in Hanover, Massachusetts, and Rocky’s two children, thirty-two-year old Mary Ann and sixteen-year-old Rocky junior, had been flown to Vegas …” wrote Holmes in his autobiography, “In the weeks leading up to the bout, they were interviewed more than Spinks and me.” He continued, “Peter told the press that he was hoping I didn’t break his brother’s record—that he was praying and lighting candles that I wouldn’t win. That aggravated me because records are made to be broken.” And, “With all this attention to Marciano, I was set up as the Darth Vader to Marciano’s white knight. I didn’t like it at all. As a champion I had not avoided any challenge, taking on the best contenders and beating them all. What’s more, I had done nothing to disgrace the title, living a clean life, without incident.” ¹ There is anger in Holmes’s words but also a deep sense of injury. He cries like a wounded man. Why can he not be accepted by the white public as a hero in the same way that Marciano was? Is he not just as good a role model as Marciano was? If anything, the opponents Holmes faced were tougher than Marciano’s. Ought not the press be rooting for him to break the record? Alas, for African Americans, there is always the crippling suspicion that when they show up at the house party wearing their best and flashing the invitation, the owners are reluctant to let them in. They are always strangers in the neighborhood where, in fact, they live.

On the other hand, why would Marciano’s brother root for Holmes to win or even be indifferent or neutral about whether he won? It seems natural that he would want his brother’s record to remain unmatched and unbroken, that he would pray for Holmes to lose. That seems only honest. If the situation were reversed, one would expect Holmes’s brother to be opposed to any fighter breaking any record that Holmes might hold. If Italians held a special affection for Marciano, that would only be expected too. Boxing is a sport that highlights and exploits ethnic rivalries. Boxing has always been show business built on blood and identity politics; the latter before the term was even imagined. As Saint Thug and one-time heavyweight champion Sonny Liston put it, “In boxing, somebody’s got to be the bad guy.” And so it is with identity politics as well. Somebody has to be the hegemon or what’s an oppositional identity for? In an interracial fight, it is easier to sell high-rent tickets if, most of the time, the black guy is the bad guy for the white audience. In the Bizarro world of boxing, the black guy has often been imagined as the oppositional gatecrasher pitted against the righteous white hegemon and so identity politics gets stood on its head. That is why, in the marvelous entertainment known as boxing, it is not good for a minority fighter to be overly sensitive or overly self-conscious about being a minority. Only Muhammad Ali was able to sell that shtick.

Michael Spinks became the first light heavyweight champion to win the heavyweight title when he beat Larry Holmes in September 1985 in a very close fight, a fight so close that under any other circumstances than the Marciano record being at stake Holmes might certainly have won because Spinks had not done enough to take a champion’s belt. Ali had taken more punishment in fights in the latter part of his career and still retained his title than Holmes took against Spinks. “I’m thirty-five fighting young men and he [Marciano] was twenty-five, fighting old men,” Holmes said bitterly after the fight. He then added, infamously, “To be technical, Rocky Marciano couldn’t carry my jockstrap. They didn’t want me to win because people want a white hope.” It never helps a black person to be publicly bitter about his or her race; here, Holmes just seemed a very bad loser. Of course, few great athletes have ever been good losers. As Izzy Gold remarked about Marciano and his friends as boy athletes: “‘We were lousy losers. The only thing that mattered was to win. … The Rock was never a good sport about losing. He’d never think of congratulating a guy for beating him.’” ² Since Marciano never lost a professional boxing match, we will never know how bad a loser he might have been. In fairness to Holmes, he wound up not only failing to tie Marciano’s record but losing his title as well, which he would never get back.

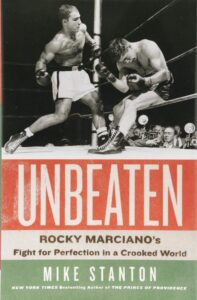

To add insult to injury, Holmes lost the rematch the following year in another equally close fight. In having Holmes lose the second fight, I suppose the ghost of Rocky Marciano just wanted to make sure no one doubted the outcome of the first fight. Another way of looking at this is that Holmes needed to win the fight decisively, commandingly, because the record was at stake. In order for fans to accept it, in order for Holmes to have a measure of peace, because of the emotional stake so many had in Marciano’s record, Holmes had to rise to a certain level of undoubted, unquestioned, self-evident excellence, not just squeak by. Some might say that such an expectation is, on its face, unfair. But boxing is a frequently unfair and crushingly unforgiving sport. Even before the fight started, Holmes knew this as well as anyone on that particular September night. And being black, if not quite unfair in our inclusive and diverse world of tomorrow, is, shall we say, still, at times, more than a bit inconvenient. As Marciano biographer Mike Stanton writes, “In 2012, when the city of Brockton dedicated a statue of Rocky, Holmes attended the ceremony.” (313) Even Holmes was bound to respect, as he knew more than anyone else, how hard Marciano’s feat was.

- Marciano as the King of the 1950s

America is a cruel place if you don’t know your way around.

—Marciano’s childhood friend Izzy Gold (22)

As in the two earlier Marciano biographies³, Stanton’s Unbeaten tells this story: Rocco Francis Marchegiano was born in 1924 in Brockton, Massachusetts, his parents were Pierino, an Italian immigrant who never fully recovered from being wounded and gassed in World War I and who worked making shoes (the major industry of Brockton) and Pasqualena, also an Italian immigrant, who bore six children. Rocco was the first surviving child. He nearly died of pneumonia at the age of two but otherwise had a stout constitution, an enormous appetite for food, and a restlessness that plagued him for his entire life. Rocco was no angel but he was not a particularly bad boy. He was tough, stocky, strong, did not mind fighting other kids but was not a bully. He sometimes stole, sometimes played pranks but did nothing criminal as a child. He hated school, disliked reading, and eventually quit despite his mother’s hopes that education would be his ticket to a better life, that he become a doctor or some sort of white-collar professional. She had wanted to be a schoolteacher but her Old World father hit her over the head with a chair to convince her that education was not for women. (15) His father did not want him to wind up in a shoe factory. He himself did not want to end up like his father. He hated the dead-jobs he took once he quit school. His lone hope was sports which was the only thing about school he liked. He wanted to be a baseball player. But despite his strength, he was not ideal material for being a high-performance athlete. His thick legs made him a ponderous runner. (As the old saying goes, he ran as if he were carrying a piano on his back.) He might have made a passable or even decent football player but professional football in the late 1940s was no place to gain fame or make lots of money. His arm was too weak and his running too slow for him to make it as a professional baseball player. What was left was boxing which, during his childhood and adolescence, was a far more popular sport than it is today. Indeed, even after World War II, boxing remained the second most popular sport in the United States only exceeded as a box office attraction by baseball. In the early 1950s, boxing dominated the new medium of television, broadcast nearly every night of the week. Boxing could give young Rocco the two things he most craved: fortune and glory, as Indiana Jones put it.

The secret for success in sports is to be willing to sacrifice everything in outworking your opponent. Rocco Marchegiano did just that and in the process was reborn as Rocky Marciano.

But as Stanton writes, “Rocky was an unlikely champion. He didn’t start boxing seriously until age twenty-four and was often overmatched in size and skill. He was five foot ten and weighed 185 pounds, with short, stubby arms, clumsy feet, and a bulldozer style that opened him up to fierce punishment.” (4) In his early days as a fighter, despite his powerful, numbing punches, most of the knowing coves in the trade did not think he had a chance to be successful, let alone a champion. He was so inept and off-balance that he would sometimes fall flat on his face throwing a haymaker. What Rocco had, aside from incredible punching power was an extraordinary determination to train, to learn his craft, to dedicate himself to the harsh, lonely regimen of the boxing life. He did this not out of love for boxing but out of desperation. If he did not succeed as a boxer, he felt there was nothing left for him but a dead-end life of dead-end jobs, of life being a working-class nobody, traveling on a path to nowhere with no way to get there, of being lost while caught in a trap. The cruelty of an anonymous, pointless life frightened him far more than the cruelty of the ring. The secret for success in sports is to be willing to sacrifice everything in outworking your opponent. Rocco Marchegiano did just that and in the process was reborn as Rocky Marciano.

Serendipity is the handmaid of ambition. Rocky came along at an ideal time, the post-World War II era of the late 1940s. The heavyweight division had been dominated by Joe Louis who had emerged in the 1930s as a force of nature and of social change. He won the championship in 1937, the first time a black was permitted to fight for the heavyweight title in 22 years or since the notorious or rebellious (take your pick) Jack Johnson so ignominiously lost it in Havana, Cuba in 1915. Louis, lionized by blacks, would become the Great American Hero when he beat Nazi Germany’s Max Schmelling in their rematch in 1938. (Louis lost to Schmelling in 1936.) Louis would become a symbol of America during World War II, providing history with one of the most famous quotes from the war, “… we’ll win because we’re on God’s side.” (He was supposed to say, “God’s on our side.”) Louis defended his title 25 times and held it for 12 years, longer than any other champion. But by the 1940s, Louis was old, sick of boxing, and looking for a way out. He sold his title to the International Boxing Club for a sum of money he never got and the boxing scene lost its mythic hero. New black champions emerged such as Ezzard Charles, the Cincinnati Cobra, and the aging Jersey Joe Walcott, but the white public, to be sure, was tired of black champions and these two lacked the historical and sociological depth of Louis. The world was ripe for a white champion. Enter Marciano.

Marciano, under the tutelage of veteran trainer Charley Goldman and wily, double-dealing, loudmouth manager Al Weill, climbed the ladder of his profession. That is to say, he started the climb after Weill was finally convinced that Marciano was worth managing, that he could be a meal ticket. This was not obvious to even his gimlet, greedy eye at first, Marciano, despite his knockout power, looking so inept in the ring. Weill, while Marciano’s manager, was also the matchmaker at Madison Square Garden, a clear conflict of interest, but in the world of boxing such graft and corruption were normal. After all, the mob completely controlled boxing in the 1950s through the International Boxing Club. It was a sewer of fixed fights, racism, deaths in the ring, and broke and broken-down fighters who left the sport, in most instances, much worse than when they entered it. As one famous boxing promoter put it, “Boxers are like whores.” And both, one supposes, are like Kleenex or toilet paper. Whores, too, leave their profession worse than when they entered it. Feminists should keep that in mind when they speak of the sex trade as a form of empowerment. No one in his or her right mind really thinks the fight trade is about the empowerment of fighters. Fight promoter Don King would find such a thought amusing.

New black champions emerged such as Ezzard Charles, the Cincinnati Cobra, and the aging Jersey Joe Walcott, but the white public, to be sure, was tired of black champions and these two lacked the historical and sociological depth of Louis. The world was ripe for a white champion. Enter Marciano.

Marciano had three things going for him: first, he was white which made him both refreshing and retrograde image of masculinity for the heavyweight championship; second, he was Italian, a white urban ethnic, which meant he reinvigorated the notion of the American Dream and the Melting Pot in Cold War America; third, he was a tremendous puncher who knocked out most of his opponents but even as he improved lacked real ring artistry. His fights were wars of attrition, not tactical contests. This meant that he was a gate attraction even for people who were not fans of boxing. Knockouts in boxing are like home runs in baseball, dramatic and game-changing.

Larry Holmes was right. Marciano did beat old black men during his championship run: a worn-out, 37-year old Joe Louis in 1951 who had returned to boxing because of his income tax debt; an aged Jersey Joe Walcott in 1952 and 1953 when Walcott was probably over 40 years old; a battle-weary Ezzard Charles in 1954 when Charles was 33; and finally light-heavyweight champion Archie Moore in 1955 when Moore was at least 39 years old. Timing is everything, as it is said, and Marciano or the fates timed his career just right. But then again there was nothing wrong or suspect about how Marciano’s career was handled. In the fight game, good young fighters eat old ex-champs in this unsentimental cuisine of social Darwinism. Eat a meal or be one, is the motto of boxing. Holmes’s reaction to his loss to Michael Spinks might best be described by a chapter title from one of Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels: “He disagreed with something that ate him.”

He is the ethnic white as heroic underdog, a variant of the form of white American innocence that one finds fairly frequently in popular culture in the depiction of white rural people from Howard Hawks’s film Sergeant York to Al Capp’s comic strip Li’l Abner to the television series The Beverly Hillbillies.

Marciano was conscious of his image. As Stanton writes, “Rocky vowed to be a role model for children and to be a popular champion like Jack Dempsey, always happy to sign autographs. He appreciated his humble roots and didn’t want to do anything to tarnish his crown. America was eager to embrace him.” (214) He avoided drinking and smoking, both of which he did before becoming a serious boxer. “‘I didn’t belong to myself anymore. In a way, I belonged to everybody who had an interest in me,’” Marciano said. (216) Marciano was clean in a dirty game, an innocent swimming in a sea of corruption. This contrast is precisely what Sylvester Stallone emphasized in the first Rocky film and the overall characterization of the famous celluloid boxer. Rocky fights like Marciano, absorbing tremendous punishment but landing fearsome blows, trains with the same work ethic, seems always the good guy in his fights. He is the ethnic white as heroic underdog, a variant of the form of white American innocence that one finds fairly frequently in popular culture in the depiction of white rural people from Howard Hawks’s film Sergeant York to Al Capp’s comic strip Li’l Abner to the television series The Beverly Hillbillies.

After boxing, Marciano was unable to shake the restlessness that always afflicted him. Perhaps to compensate for the Spartan life he endured during his boxing days, he had numerous affairs. He also, as Stanton writes, “fell into a nomadic lifestyle. He traveled around the country and around the world in an endless loop of speaking engagements, business meetings, charity dinners, television appearances, and boxing events. He might be in Chicago one day, Minneapolis the next, then on to Denver, with a stopover in Omaha. People paid for his plane tickets, hotels, meals, and any other expenses. Often, he would show up in rumpled khakis and a T-shirt and his hosts would outfit him with a new suit.” (276) It was the soft life one supposes he always wanted or felt that he had earned but yet did not seem to satisfy or fulfill him.

One of his odd habits was insisting that all his business transactions be done in cash, that his fees and honoraria be paid in cash. “He carried [cash] around in paper bags, as much as $50,000, and stashed it in bizarre places—pipes, curtain rods, drop ceilings, toilet bowl tanks—because he didn’t trust banks. His pockets jangled with keys to safety deposit boxes where he also stashed cash, but he kept no records of their whereabouts.” (277) In this respect, he never outgrew the old folkways and superstitions of his working-class immigrant origins. He had the immigrant’s habit of being cheap, stingy, a sponge but yet he wasted enormous sums of money on bad business deals. He did not understand money except he could not bear to be without it. Perhaps his restlessness was the result of his attempt to outrun the identity that he simultaneously embraced. He did not want to be himself but he did not want to be anything else. Perhaps his restlessness mirrored the restlessness of 1950s America, the dark turbulence beneath the sweetness and light of success. Being affluent is never as compelling, never even as interesting, as desiring it. Sometimes, being hungry is better than enjoying a banquet.