Documentary filmmaker Ric Burns

Ric Burns is serving humanity one sound bite at a time. Using spontaneous inflections and gestures to dramatize his encyclopedic command of historic facts, the filmmaker, dressed in jeans and an orange T-shirt over a white one, took two hours from his busy schedule to offer some insights into his specialty: turning crucial histories into documentary films. At Steeplechase Films, the five Emmys on an outer-office shelf, along with dozens of other prestigious awards above the no-nonsense desks, files, and Steeplechase staff say it all: it takes a vision and teamwork to achieve brilliant results.

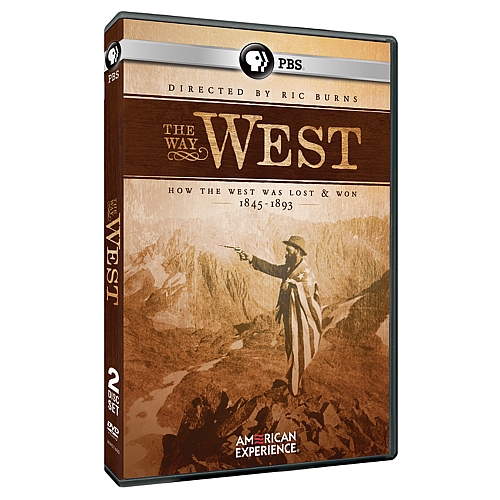

Burns received two Emmys (editing and producing) for his eight-part documentary New York; two Emmys (producing and writing) for the PBS Civil War series; and an Emmy (outstanding cultural programming) for Ansel Adams. He has received the Alfred I. duPont-Columbia University Award for his New York, Civil War, and The Way West documentaries, along with numerous other awards for outstanding achievement. His range of documentary subjects includes the Civil War, Coney Island, the Donner Party, westward expansion, Ansel Adams, Andy Warhol, Eugene O’Neill, immigration in New York, and whaling in America.

The following interview took place October 27, 2010 at Steeplechase Films in New York City.

On storytelling in history and film

Jan Castro: Ric, when you and your brother [Ken Burns] were growing up, what exactly did your father do as a cultural anthropologist? Did he do field research?

Ric Burns: Our dad was a cultural anthropologist studying a high-alpine village in France, Savaron, Cité Classé, the highest French village tucked up near the Italian border. He had found this place in the early 1950s and took Ken there when Ken was an infant. I was conceived there. That was the only work he ever did as an anthropologist. He was really drawn to the culture of this tiny, high-alpine community which had sustained itself on agriculture for a couple of thousand years—incredible, 1500-year-old stone irrigation ditches. Then in the winter, they would drive their animals down to winter pasture and spend the winter as scriveners and translators. This little community had a highly literate side and an agricultural side.

Because of the impact of the Second World War—young men going off to war and coming back with skills their fathers didn’t have—and millennial rains in the early 1950s which had washed away this stone irrigation system at exactly the moment that the inner structure of their social life was being washed away, these two events were upsetting the patriarchy of the village. Basically, it was a little world in the middle of cataclysmic transformations in the early 1950s, and he wanted to study that.

Savaron had a kind of legendary, Brigadoon-like quality for Ken and me both, in ways that are kind of dark as well as warm. Father never finished his PhD and somehow lost his way in a number of ways, partly because our mother got ill with cancer when we were tiny and died when I was ten and Ken was eleven and a half. So this unfinished, very rich, complicated body of work about this remarkably beautiful, austere place perched on top of a mountain in southeastern France exerted a kind of force for Ken and me that was very large and also, in certain ways, troubling. Our father was a storyteller, a voluble talker, shy in certain ways, and sensitive. He loved to impart what he knew and would give us multichapter histories of the Second World War when I was six and Ken was eight—every night after dinner in fascinating detail: submarine warfare, the Battle of the Bulge—and some way of learning as much as you can about something and finding whomever you can to tell it to at great length got imparted if not with our mother’s milk then with our father’s genial madness. He was a complicated person.

JC: That’s amazing. Your love of narrative, perhaps, owes something to your father’s storytelling.

RB: I think so. It was not anything reflected on at the time, but, you know, film is the most tyrannically narrative medium. It really has to be narrative. Film runs through the gate of a film camera at twenty-four frames a second, or thirty in video, and is projected back out at twenty-four or thirty frames a second. Even though you can stop it and reverse it, it’s a narrow, liquid river of light and shadow and sound moving in one direction. There’s a profound arrow of time moving forward which requires that the data you manipulate—sound, words, images, music—those elements must be arranged narratively, and to the degree that a film doesn’t do that it’s felt as friction, boredom, repetition, lack of clarity. And when it is felt, the whole is much greater than the sum of the parts.

It’s interesting: Ken first and then, through Ken, I, as well, was so powerfully drawn to this most storytelling of all storytelling mediums. Its gift is that; its limitation is that; its beauty is that. Even if you make a hugely long film, it’s still got to move like a freight train or it fails. That freight train is the story.

Film is so newfangled and modern-seeming, but human beings, for a hundred thousand years, have been gathering in a darkened place and staring into the fire and telling stories to each other to ward off the darkness. Film does exactly that. We all have that experience. It’s not even a metaphor. The lights go down in a movie theater. You look at an image on the screen, and it kind of crawls into your nervous system in a primal way. Through that medium—the flickering in the cave—you are taken to a place where you want to have asked and have answered the most basic question: What happened next? It’s astonishing how powerful it is; human beings will always be drawn to it. It’s the main way we make sense of our world, by telling stories about it.

On the American vernacular and making The Civil War

JC: How did you initially move from being a literature student at Columbia and Cambridge universities into making The Civil War with your brother, Ken?

RB: In high school, I was a wastrel, an underachiever, and a good drummer in a band called Suzy and the Pimps. Ken was a straight-A student. He then went to a strange little place, Hampshire College (nobody had heard of it), and I went in the other direction, to Columbia and Cambridge. I was sure I was going to be a professor of English literature.

But Ken would farm out chores—writing proposals for his first film, Brooklyn Bridge, or working on parts of scripts for his wonderful film on Huey Long and other projects. I had the great good fortune of being with this incredibly gifted person at exactly the moment when I was going, “You know, I don’t want to spend forty or fifty years writing three books for an audience of two thousand.” That is a great thing to do, but it didn’t fit my aptitude. The good fortune is that my brother had proactively found something that fit him that also, surprise of genetics, fit me in ways that are similar and different. So in the mid-1980s, Ken was thinking about doing a larger film on the Civil War and asked me to come and produce it with him. I jumped at the opportunity and never looked back. That turned into five amazing years from 1985 until 1990 that were formative for me at a very deep level.

I have to say, for all of us, you don’t lose anything. The twelve years I spent in college and graduate school here and in England live inside me warmly and deeply.

JC: How did you conduct the research for The Civil War during those five years? Did you start out with themes, or did any new ones emerge?

RB: It was a pretty closely held proposition. There was Ken and me and Geoffrey C. Ward. Geoff and I wrote the series with Ken. There were a couple of researchers, Mike Hill and, later, Kitty Isley. Lynn Novick, Ken’s partner today, came in at the end. We assembled a board of consultants and asked them not to review treatments and scripts but to bring us material. The Sullivan Ballou letter came over the transom from the great scholar Don Feinbach, who happened to know it and made it available. Much of the raw building materials came from the two or three dozen men and women on our board. Barbara Fields knew of this ex-slave, Spotswood Rice, who escaped from his Missouri owner and wrote a scathing letter back to her. Shelby Foote had a zillion suggestions both on and off camera. From beginning to end, the visuals were there to create contexts and circumstances in which the remarkable language of Americans then—whether it’s Ulysses S. Grant or Jefferson Davis or Spotswood Rice—or Americans now. It’s impossible for me to separate the impact that series had from the distinctive American vernacular of the two dozen American men and women who spoke on camera about it. Shelby Foote was obviously front and center, but many people, when they spoke about the Civil War, spoke about something they knew was one of the most important things they could speak about. So it was a twelve-hour story told around its own campfire. It’s hair-raising to this day. The equivalent casualties today would be 30 million. In the Civil War, 2 percent of our population died.

I’m about to embark on a project for PBS which takes as its point of departure Drew Faust’s extraordinary book This Republic of Suffering, which is about the impact of the number of dead during the Civil War on the culture and psyche of America. The government changed. We didn’t bury our dead. We didn’t count our dead. As a result of that war, veterans offices emerged due to the duties the government understood it had: to name and bury the dead, to notify next of kin, to account for, make reparations for those killed and maimed. It’s amazing how present the catastrophe of the Civil War still is. It’s part of who we are still. You don’t have to scratch the surface far to be reminded how that’s the case.

New York as a microcosm of America’s heritages and identity

JC: Your love affair with New York includes your eight-part, seventeen-and-a-half-hour, Emmy Award–winning series New York and, more recently, your film Neuva York at the Museo del Barrio. What was your process for exploring the city’s roots and history?

RB: In the early nineties, my colleague James Sanders, architect and writer, and I cooked up the idea of doing a long poem to New York that would go from soup to nuts. We had wonderful researchers, one of whom, Robin Espinola, is still working with me as a producer. Li-Shin Yu cut half the film and also works with me today.

The process … because film is always a story, it’s also true that any one film has to be one story. The beautiful thing about New York is that it’s a cliché to say there are 8 million people in the naked city. What is less frequently pointed out is a fact that’s just as salient. There’s a story at the center of New York about how and why it came to be that very particular, very American experiment in the early seventeenth century. However much people think of New York as the most foreign of American places, it’s really the place where democracy and capitalism—not in that order—came out of the ground to survive most vibrantly, first as a commercial colony and then as a diverse one with no ideology.

New York is a four-hundred-year experiment to see if all peoples of the world can live together in a single place. You know, when Henry Hudson rounded the tip of Coney Island in 1609, he did not go, “Aha, I am an important seminal stage in the process of globalization.” But he was. And when the Dutch founded an outpost, a commercial entrepôt for their global commercial empire, it quickly became the most demographically diverse place on earth because the Dutch were not founding Quaker Philadelphia or Puritan Boston but rather a business enterprise that needed workers, had labor shortages—needed to be seen to be open to everyone, even Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition in Brazil when they came in 1654. This powerful dynamic—that if you are nakedly, almost monomaniacally commercial, you will become diverse in your constituency.

Capitalism and democracy come boiling out of the ground at the foot of Manhattan in the early 17th century. This place becomes the petri dish, a laboratory experiment. How do you create a world that is itself constantly changing—new people, new ideas, new political values, new lifestyles, new problems? A place singularly unbeholden to any one group or to the past? How do you create a world for all of these people?

New York becomes a model of what the world is going to look like four hundred years later: very small, everybody crowded in together, everybody having to find some modus vivendi. That was the story we wanted to tell. For me, it was the project of a lifetime. More than anything I’ve worked on before, there was no model for how to tell the story. I feel tremendous pride and gratitude that my colleague James and I created a story that feels resonant, plausible: how to take 325 square miles of Greater New York and four hundred years of history and all these people, all these enterprises and find a path through it. It obviously leaves out a huge amount.

It almost killed us to make it. It was the toughest project I’ve ever done by far.

JC: You won many Emmys for it?

RB: Yes, we got an Emmy for editing, an Emmy for writing—nobody’s Mozart. To make anything that’s resonant for two minutes takes an avoirdupois rocket fuel amount of effort no matter whether you’re making a table, an article, or a film. All of us know that time equals quality. I feel fortunate to have found my way into this field where if you’re foolish enough to want to put in whatever time it takes, if the subject’s right, you can create something that stands a chance of being resonant.

Immigration as a two-way journey

JC: Your Nueva York film documents the waves of immigration to New York from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Mexico.

RB: One of the most jubilant discoveries I’ve made in the last couple of years is staring us all in the face—the longest, largest, and most powerful demographic, political, social, and cultural transformation in the United States since it began is happening all around us. Roughly speaking, the Caribbean and the Southern Hemisphere is moving north. It started in a powerful way in the 1920s, picked up speed with Puerto Ricans after the Second World War. This 150-year migration has dwarfed anything that has come before it. America will become the largest Spanish-speaking country in the world sometime during this century. We’ve absorbed so many different people, nationalities, customs, but we have not become a bilingual nation as a result.

America will become a bilingual nation. This is viewed controversially. Many people feel the American dream is coming to a resounding, cataclysmic end. There’s a sense that these many different Spanish-speaking peoples who are becoming part not only of New York but of the entire United States are bringing with them the vigor and vibrancy of a culture which is changing us as much as they are being changed. I think that rather than be frightened of it, we should see it as the realization that if the American dream means anything, it’s going to be writ large in this true rendering of America as a cosmopolitan place.

The melting pot no longer goes, “everybody comes here, learns how to speak English, and America becomes wealthier per capita as a result.” It’s a vastly more complicated thing. We owe our being to people on the other side of the world, whether they’re Chinese or Spanish or African or Asian. The least attractive aspect of American reality, which we know in our bones isn’t true, is the whole idea of American exceptionalism. It’s founded on the paradox that there is no “America.” We came from other places from the very beginning. The Dutch, the slaves came from someplace else. Everybody. The Native Americans walked over the land bridge at the Bering Straits. We’re all from someplace else. And it was the degree to which we somehow spent hundreds of years imagining an essentialized America that is somehow special and different and set apart from the world—whereas, in fact, what we always knew, in another chamber of our heart, is that America has always been the “coming together” place, not the place that’s set apart.

What “Neuva York” means, if it means anything, is the salutary surrendering of what’s been most constraining about the American identity and the embracing of an American identity of such tremendous vibrancy is literally the most hopeful set of emotional and intellectual experiences I’ve had in my working life. It’s really thrilling to see it. I can’t wait to get to this project in a longer form than half an hour.

JC: I subscribe to your sentiments. At the same time, the film touches, perhaps too briefly, on political hot-button issues, such as a past American president’s support of Latin American dictators, the president’s lack of support for labor movements, the rise of gangs, and black–Puerto Rican rivalries. How do you weigh and balance reporting on conflicts and promoting diversity and pan-Latin progressive developments?

RB: What’s difficult and sobering about the story, which in our 20-minute film you can scarcely touch on, is not separate from what’s ennobling. For 150 years, our hemisphere has been our labor pool, our resource pool, our sphere of domination. Only someone who resoundingly has his head in the sand and not in reality will turn away from or deny that America has had a subordinating relationship to places like Cuba, Puerto Rico, other places in the Caribbean, Mexico, Central and South America—places rich in resources we’ve wanted, labor we’ve needed, and from which we benefitted tremendously by relationships with powerfully repressive regimes through whom our business interests were the chief beneficiaries. America… Juan Gonzales makes this point very clearly in our film; it’s the most salient point: globalization as a centrifugal projection of business interests is what we think of as globalization, but the fact is that when those business interests go and distort the economies of the places they visit, the other side of globalization is the people who live there come back at us as men and women looking for a livelihood. We will never have globalization as a universal projection of markets and not have it also as universal movements of people.

For us, that has meant people from all over the world and people from our hemisphere coming here looking for jobs they don’t have at home, for all sorts of reasons, some of which is the degree to which their local economy has been distorted by American business interests. We have a moral connection, an economic connection, a human connection, an experiential connection. It cannot be an accident that we are all called Americans. We have been in and out of each others’ pockets for a very long time, and it’s just going to get more and more so.

Art that recognizes unseen universals

JC: To go in another direction, your Andy Warhol and Ansel Adams films both dwell, especially the Warhol film, on each artist’s childhood passions and problems. I believe both were strongly supported by their mothers, homeschooling was involved, and one or both were dyslexic or had learning disabilities.

RB: Both were hyperactive, with a little dyslexia in Ansel’s case, severely dyslexic in Andy’s case, with a kind of autism or Asperger’s also.

JC: Are you suggesting these early stigmas were important and contributed to the obsessions each had with making art? You’re recognizing individuals who are a little different.

RB: George Plimpton put it well about Warhol: “You know, Andy liked to say that he’d had thirteen nervous breakdowns by the time he was thirteen years old.” Plimpton recounts how Andy would fixate or stare at something, like a soup can, for a long time. There is something about the temporality of a certain way some people are hardwired. Without attempting to romanticize an unusual kind of hardwiring, people who are more attentive to reality see things that the rest of us don’t see until another form of obsessive-compulsive disorder, which we call art, focuses our attention, and, by bringing a concentration, a density, and sometimes even a tyrannical order, makes us look, listen with particularly acute concentration. Andy Warhol’s films were meant to be shown slightly slowed down; Warhol scholars know with certainty that was the way Andy saw the world. He might be talking to you right now and see a beautiful reflection in your eye that’s meaningless and accidental, but look at that! We have a whole set of social constructs to protect ourselves from an intensity of perceiving. It’s that naked, but in defending ourselves we also block ourselves from an awareness of the world around us. So there’s kind of a zen to Andy Warhol and a zen to Ansel Adams.

Ansel’s photography was not purely realistic. His main breakthrough came when he realized that certain filters could heighten contrasts and darken the sky, make Half Dome jump out in a certain way. It was a higher lyrical truth: the experience of this rock was heightened by the artificiality. Therefore, you could feel—as John Szarkowski, the [deceased former] head of the photography department at MoMA put it—Ansel was creating records not of the outside world but of his experience of the outside world. There’s an inner fidelity which the object you create is meant to honor. It didn’t quite look like that; it felt like that. You only get that through the same double obsessiveness: first, the rapturous obsessiveness of finding the world beautiful in ways that are almost scary. Obsession two is: I have that feeling inside me; I’m going to get it, in some form, outside me so that you, Jan, can feel what I felt. Then you’ve launched this project to build something, paint something, photograph something, and the sounding board is, “That’s it.” So, don’t say they’re disabled. Say they’re alternatively enabled—blighted, obsessed, and fantastically gifted.

All of us understand what the blessing is. Eugene O’Neill would have been better if he’d been a better dad. All of his children either killed themselves or drank themselves to death. But, at another level, he saw something and felt something very, very, very deeply. He couldn’t not feel it. He was cursed and blessed with that raw sensitivity. He was trapped by it. He then did the thing that was unusual. He made something you recognize, and you’re going to go, “right, that’s my family.” As was often pointed out about Shakespeare, you see in what he wrote recognizable versions of the world you see around you. The greatest artists always do that. Their creativity is in finding the deep pattern, finding the DNA of what it means to be human. They’re scientists of human experiential reality. You go, “aha”—that uncanny feeling that you’re recognizing some deep reality. For me, working on these artists is the deepest thing I can do. For all the danger of art and all the edginess of it, it’s the thing that brings us together.

JC: Did you choose the artists?

RB: All the artists came to me. Eugene O’Neill came through Arthur and Barbara Gelb, O’Neill’s early great biographers. The Sierra Club called one day and said, “Do you want to do a film about Ansel Adams?” Two guys in 2000 met with me about Andy Warhol. Somebody just knocked on the door in each case. It’s taught me that it’s really easy to become your own worst cliché and to repeat yourself, to keep doing what you’ve done. One of the only ways I know to fight against the grain of that is, Don’t succumb to the vanity of thinking you have to do the work you’ve chosen.

The Central Park of the mind

JC: So you don’t have a big list of future projects?

RB: I do. I want to do a big film about Shakespeare, surprise, surprise. When Louise Mirrer, president and CEO of the New-York Historical Society, came to me about doing a film about Nueva York for the New-York Historical Society, I thought, I’m on the board, I’m not going to get paid for it, but how can I not do it? As I looked into it, I opened doors which, through my own fault, I had not opened widely enough. It’s worth going around the barn the other way to see what’s on the other side; hopefully, you escape some shadows of your own habits.

JC: The cinematography for that film was so fresh—colorful, dramatic, for the most part, not focusing on the experts but on the people on the street.

RB: The few places where we shot for that little film—Sunset Park in Brooklyn, out in Queens, or 116th Street in East Harlem under the elevated train, which has had repeated waves of Latino migrations—the camera is seeing something real.

JC: Do you work with one composer?

RB: We do. Brian Keane is incredible.

JC: He has a huge range.

RB: He’s brought such a focus to each project. He’s toured with Turkish bands. Professionally, he’s been in many different circumstances. Like a doctor who knows his patient, he knows who we are. It’s a collaboration at the heart of the project, an alert physical openness not dominated by the brain. Movies are not made on the screen. They’re chains of events made inside people.

JC: I have a question about the roles of women both in your films and in your production company. The Donner Party was fascinating both for the harrowing story of survival and the odd fact that somehow more women than men in the party survived.

RB: The survival rate of the women has been thought about from many different angles: nutritional, gender studies, anthropological. There are some salient sociological realities: nineteen of the twenty-two single men died. So, if you were not part of an extended family grouping, you were not going to make it. There have been insider analyses of the higher survival rate of women that have to do with calorie expenditure during stress. It is thought, in some quarters, that the male response to stress is testosterone-related: to expend calories to try to change the circumstances you’re in. When you’re basically trapped with very little to eat, concentrated calorie expenditure is a disaster. What seems to be connected to higher estrogen levels is an alertness to what can and can’t be changed in the immediate set of circumstances. That quality, statistically found more in women than in men, may be biologically coded. Finally, women may have more subcutaneous fat or stored food supplies.

JC: It was surprising to me to learn that Melville’s Moby-Dick was a failure in his lifetime and ruined his writing career.

RB: Right. There is such a thing as being ahead of your time, and Melville is one of the greatest examples of it. You can also be “out of time.” He started writing when the sea was a hot topic and wrote his magnum opus—the great novel about America—when our attention was shifting from the ocean wilderness to the western wilderness. We have Melville’s response to Hawthorne’s review of his novel in his house in Lenox. The person most important to him, Hawthorne, got it. No human being has ever written like that. Moby-Dick is a life-changing experience and is moving the way Shakespeare is moving. The passages that build and roll are so ravishing and the language is so exalted. That must be its own gratification. The pain of doing what he had to do—and he didn’t miss it by much. It is indubitably the great American novel [emphasis added]. Imagine what it was like to be living in this country in 1850, 1851 on the eve of the Civil War. The plates were shifting; things were looming. Melville was so aware of it. He knew he had found a natural parable of a society full of enormous promise blighted by enormous darkness.

JC: The increasingly widespread quest for whale oil then is a metaphor for the oil industry’s greed for oil today.

RB: It’s resonant in a way that can be really surprising. You go whaling in three-masted ships. It’s not quaint and gone. It’s the same old thing.

JC: Laurie Anderson was influenced by Moby-Dick, and she’s one of the many voices in your films.

RB: She was. She was the inevitable person to narrate our Andy Warhol film. One of our colleagues, Daniel Wolf, had the idea, and he was so right. She’s one of seven children, trained as a musician, grew up in Chicago. That narration is so demanding to read. She brought to it a real discipline: quiet focus, subtle inside things with inflection and speed. With Laurie, the idea that you had to do something twenty-two times was perfectly natural. Her clinical, idiosyncratic monotone was perfect for Andy Warhol.

JC: Do you cast all the voices?

RB: Danny Wolf also had the idea of Jeff Koons as Andy Warhol. We had actually tried two extremely gifted actors who were both fantastic in a certain way. With Jeff, even though he doesn’t sound anything like Andy Warhol, there was a rapturous, not faux-naïf voice saying “time is, time was.” Whatever that means, Jeff got that completely. There is a different temporality. You have to really hear the words they’re saying; the microphone in these recording studios registers an attention that is the lifeblood of these movies.

JC: The documentary, the visuals, and the soundtracks are riveting. I would like to talk briefly about your introducing reenactments. In your Tecumseh’s Vision film, you and Chris Eyre chose to introduce aesthetic metaphors.

RB: I am not opposed to reenactments, but I think that most of the time they don’t work. We thought long and hard about why they don’t work. To start with the conclusion we arrived at: in a movie, there has to be a ratio between things that are disclosed and held back, what the camera sees, and what is suggested. There always has to be more than what is suggested so that the imagination and the feelings of the audience become part of the shot. Then, reenactment, I’ve now discovered, is your friend. In a Jane Campion movie, there is that ratio between what you can see and what you’re forced to imagine. What we found with the whaling movie, which has reenactments in it, is that three-masted ships are the greatest thing in the world. The idea that this thing, the ship, takes a force outside of it and redirects it—they are always poised between an abysmal depth and an enormous height. Literally and metaphorically, they’re very poetic.

JC: In addition to your mastery of a range of fields from aesthetic to acoustic, let’s talk briefly about the ethics of raising money for your films. I know you’ve been criticized for working on a film about Goldman Sachs. Do you want to talk about your relationship to that?

RB: There are circumstances where I’m very happy to be employed by somebody who’s making a corporate film. The moral question you have to ask is not the one you think it is: “Is there a ‘there’ there?” If you can answer this question in the affirmative—“Is there something in the past that accounts for Goldman Sachs’s enormous success?”—then you can do the film. Where did it come from? We started working on the film in 2006–7, and then the world changed, which made it more interesting. The history is coherent, starting with a Shakespearean rivalry between Goldman and Sachs at the time of the First World War.

JC: Another four-hour film?

RB: Right now it’s three hours; we’re three months from being done. There’s no way to make this film without inside access, and, with thirty-five thousand employees, they have a right to know their own history. They had three “near death” experiences, but they did everything right. Going forward, they have to figure out what best practices to put into place. Rarely has a brand been the best of the best of the best. The appearance of conflict of interest is there, but I was intrigued by the issues. We interviewed about fifty people. The film is mainly the textures of the people talking.

JC: Is it harder to fund your documentaries?

RB: The problem is that the funding issue for public television has always been broken, but it’s now so broken that it’s hard to see how it can be repaired. These films are not cheap to make and don’t get done quickly. The easiest part is to shoot it; the hardest part is to plan to shoot it correctly and to edit it correctly. It takes more money to do an hour of these programs than is available now. An interesting crisis is going to unfold over the next decade: we can’t subsidize ourselves. You can’t just move to someplace cheaper. The hard costs can’t be reduced. Since the recession, public-television stations can’t pay their dues; programs don’t have the fee base to continue; corporations aren’t giving as much; and viewership is down. There is a huge difference between an underwriter, who can’t dictate content, and a sponsor. With public-access television, C-Span, and PBS, no ulterior motive is being served. Its model isn’t a commercial model. PBS was established by the World Congress to create broadcasting which wouldn’t otherwise be created that would reach underserved constituencies. Sadly, the trend is turning away from public television in general.

Most people I know who make films for a living are not getting rich. It’s the honest, exhilarating thrill of being able to make things that matter. Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux said that Central Park must be a place where people can breathe freely. Public television is the Central Park of the mind: close to but apart from the rapacious city, the commercial scrimmage. Public television is more embattled and more important than ever.