It’s a sliver of glass

It is life

It’s the sun

It is night

It is death

It’s a trap

It’s a gun

—Antonio Carlos Jobim’s English translation of his song “Aquas de Marco” (“Waters of March”)

“I never saw any of them again—except the cops. No way has yet been invented to say goodbye to them.”

—Raymond Chandler, the last sentence of The Long Goodbye

In the beginning

According to his death certificate, my father died on January 19, 1953, at the age of thirty-two from “brain tumor necrosis.” On another document I have, his death is described as a “brain misadventure.” Anytime our bodies turn against us, misadventure seems a good way to characterize it, a better way than malfunction. He married my mother on February 26, 1946. I was nine months old when he died. After his death, my mother remained a widow until December 29, 1979, when she married Cooper,¹ who, by virtue of this fact, became my step-father, although I was twenty-seven at the time and hardly in need of a new parent. But Cooper was not new to me. I had known him for most of my childhood as, it could be said, he was my mother’s boyfriend for many years. One reason why this courtship lasted so long was that my mother had three children by my father, two of them girls, and she was reluctant to marry again while we were children. Stepfathers have been known to do strange things to the children of their new spouses. My mother was influenced by her own mother, a domineering, opinionated Southern woman who had little education, a Democratic Committeewoman for many years. She had a sharp take on human nature, was strongly suspicious of the innate depravity in most of us. “Don’t tempt people; they love being weak,” my grandmother was fond of saying. The depravity did not bother her as much as the need people had to blame someone else for it. Cooper too had been married. His wife died of cancer, leaving him with four children. My mother was also not a strong believer that blended families were a good idea. She had made it clear to me on more than one occasion as I was growing up that she was not interested in rearing someone else’s children. So, Cooper and my mother did not marry or live together. I knew Cooper as I grew up but I did not know his children, never met them until I was an older teenager.

Our personalities did not mesh. We were not in sync as types; we had, it might be said, no rhythm in our dance with each other. Nonetheless, he was an indelible presence in my life because for nearly 30 years he served as a policeman in the city of Philadelphia (May 1954 to February 1982), no mean feat for a Black man at the time he was on the force.

Cooper died on October 3, 1994, from “acute myocardial infarction,” which is another way of saying heart attack. He was seventy and had not been in good health for a considerable time. I saw my mother cry three times in my entire life and one of them was at Cooper’s funeral where the extent of her grief did not merely touch but unnerved me. “Oh, Cooper don’t leave me. I am here all alone. What am I going to do?” She went on and on like this. I felt bad and, against my will, a bit embarrassed. She had known Cooper much longer than she had known my father. She had a right to feel that way. But she outlived Cooper by twenty-four years, so she did manage to go on without him.

None of this has any special claim on the reader’s attention. Cooper is abidingly interesting, has remained in my memory for all these years since his death, not because he married my mother, not because he was an especially good man, although he was by no means a bad one, not because I was close to him or felt him to be a father figure. For most of my life, I do not think he liked me very much and there were certainly times when I did not like him. Our personalities did not mesh. We were not in sync as types; we had, it might be said, no rhythm in our dance with each other. Nonetheless, he was an indelible presence in my life because for nearly thirty years he served as a policeman in the city of Philadelphia (May 1954 to February 1982), no mean feat for a Black man at the time he was on the force. It was his being a cop that made him so important to me. The only dead person I think about more is my mother. I think about Cooper even more than I think about my dead oldest sister. He occupies my mind and therein lies a story.

• • •

Children, Go Where I Sent Thee

For the men below who fight the foe

The lads who serve the guns

O, the men behind the guns.

—folksinger Phil Ochs’s adaptation of John Jerome Rooney’s poem “The Men Behind the Guns”

“I felt like I was somebody important that August day in 1940. After six weeks of training at the police academy, I was headed for Philadelphia’s City Hall to meet the mayor. I was all dressed up in my new blue uniform with brass buttons, a chrome badge, a sidearm, and a nightstick, and I was about to become an official member of the Philadelphia police. Fifty-one other new recruits to the force would also be attending the ceremony, but I suspected I would be singled out for special attention. I would be the only black rookie policeman in the room. In fact, I was the first black policeman to have been appointed to the force in over eight years.”

—James N. Reaves, Black Cops, 1991.² When Reaves inscribed the book for me at a 1991 book party, he wrote I should be proud of my “father” with whom Reaves had worked during his illustrious forty-year career. (He did not know that Cooper was my step-father or maybe it did not matter to him. My step-father was also at the book party.) Reaves also wrote in the inscription that “Police work is a most honorable profession.”

My mother began working as a school crossing guard on Halloween, 1955. She resigned in March 1972, when I was a student at the University of Pennsylvania. During this time, most of my friends thought my mother was a “lady cop” because she wore a white blouse, navy blue skirt, and a cap with a badge on it. In the winter, she wore a long, navy blue, double-breasted wool coat that looked almost exactly like the coats the policemen wore (until they adopted Black leather coats in the early 1960s, “to look more like the gestapo,” young Black people like my sisters said). She turned in her daily time cards to a passing police car. She picked up her weekly paychecks from the 33rd Police District office which was located at 7th and Carpenter Streets, just around the corner from where we lived. All of this intensified my friends’ belief that she was a “lady cop.” “Where is her gun?” they would ask. I could not convince them she was not a police officer, so I simply replied that lady cops were not given guns, which seemed plausible at the time.

My mother was not the only Black woman who did this work in the neighborhood. My mother worked the Italian-Catholic elementary school at 7th and Christian Streets and there was another Black woman, whose name I cannot remember, who worked at a Catholic school on 10th Street. They sometimes had coffee together when their morning shifts ended. They had three shifts a day: the morning when the children went to school, noon when the children went home for lunch and returned, and three in the afternoon, when the children were dismissed for the day. My mother liked the job because it permitted her the time to watch her own children more closely. When she left the job in 1972, her separation papers showed that her current salary was $11.25 a day. For most of the time she had the job, she earned considerably less. She got nearly $38 a month from the government because she was the widow of a WWII veteran (a man who was a lousy soldier but who did manage to get an honorable discharge). I found it hard to believe, looking at these papers shortly after my mother died, that she, my two sisters, and I not only survived but seemed to do well on such little money. I do not remember being denied any toy I ever wanted. It caused me to tremble a little.

At any rate, when I was a very young boy, four, five, six years old, my mother often took me with her when she went to get her check at the 33rd Police District. I found it exciting to see all the policemen walking around; the uniforms and the guns they wore gave me a thrill. They seemed such important men and so I thought my mother was important too. Some said hello to my mother. And they were all friendly to me. They called me “Florence’s boy.” My mother always went up to a tall wooden counter and the policeman sitting behind it handed her a check and had her sign a register. He always gave me a smile. I would smile back.

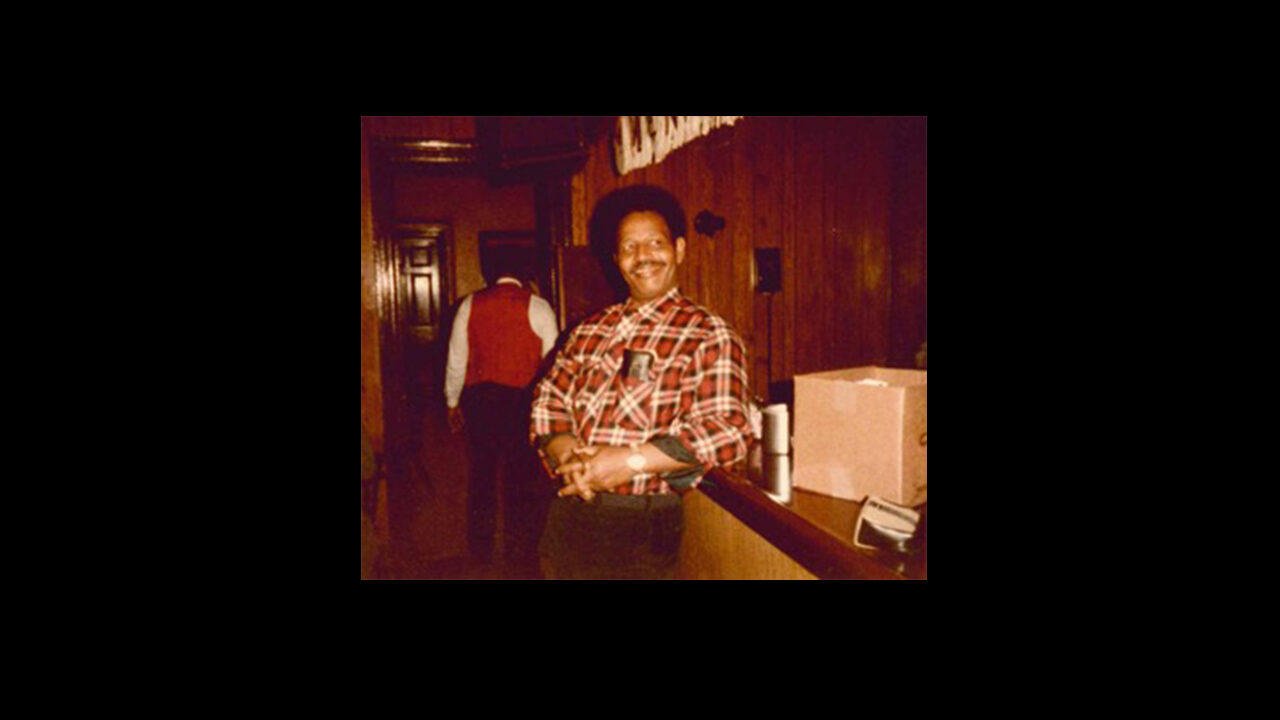

My mother probably met Cooper at the 33rd Police District because he worked out of there for a good amount of the time he was a policeman. It was certainly at the 33rd that I first saw Cooper. He had a bit of the skin color and facial structure of a Native American. He was a somewhat portly man but his weight fluctuated over the years. He seemed to get along well with the other policemen, White and Black. All of my life when I saw him with other police officers he seemed happy. They liked him. There was something manly and companionable about him. As I think about him now, the noted character actor Harold J. Stone comes to mind, whom Cooper resembled.

So, once Cooper came into my life, my family’s life, there were cops at my mother’s house all the time, hanging out. It felt like, for a time, all the Black cops in Philly were there. They were looking for Cooper, they were riding with Cooper (It was not until the 1950s, the age of liberal reform in Philadelphia city government, that Black cops were given the opportunity to use patrol cars ³), they were leaving a message for Cooper, they were waiting for Cooper. My sisters and I got to know some of these men well and to like them immensely. They were young, handsome, military veterans. They wore their crisp uniforms well, straight-back, slim hips, serious faces. They had guns and the authority that went with being armed men of the law. And they were smart, the smartest men I knew at the time, the smartest men I thought I would ever know. Some of them had read James Baldwin and Albert Camus and talked about what they had read. I heard one talk about Ernest Hemingway to my sister who was reading The Sun Also Rises at the time. He had read a book about bullfighting that Hemingway wrote and he and my sister talked about bullfighting and Spain and that led to them talking about a poet named Frederico García Lorca. Another talked to my other sister about a playwright/poet named LeRoi Jones. They played chess and taught me and my sisters how to play. They taught me how to watch football and basketball games. They knew how to fix things and sometimes did minor repair work for my mother. They knew about the civil rights movement and politics and talked about how the Negro was moving ahead and had to get more militant, how the Negro had to learn about African colonialism and quit bootlicking for the White man or, as they sometimes called him, Mr. Charlie. I swooned over them like a young girl in love. They were the men I, a forlorn fatherless boy eager for male models, aspired to be. They were the glorious men behind the guns, the Lawmen. When I was eight, I told my mother I wanted to be a policeman when I grew up; her lukewarm response was “We’ll see.”

They [the Black cops of Philadelphia] knew about the civil rights movement and politics and talked about how the Negro was moving ahead and had to get more militant, how the Negro had to learn about African colonialism and quit bootlicking for the White man or, as they sometimes called him, Mr. Charlie. I swooned over them like a young girl in love.

But they did not necessarily speak well of being policemen. They complained bitterly about the racism they endured, how they could not get promotions because of “white boy politics,” how the FOP (the Fraternal Order of Police) worked only for the White cops, how Internal Affairs went harder on Black cops who messed up than White ones, how easy it was for Black cops to get fired for something that a White cop was only reprimanded for. They complained about corruption: cops who were on the take, about how certain people could not be arrested even if they committed a crime in front of their faces. Yet they also complained about Black cops who had passed exams and were promoted to plainclothes work and to sergeant or lieutenant or, unbelievably, captain. They accused them of being Uncle Toms, not looking out for the Negro cops, taking the side of Mr. Charlie.⁴ When one of the men who hung around my mom’s house was promoted to detective, he was no longer in their circle and was often criticized for “forgetting who he was and what he came from.” Yet they all loved and respected him so before he got the promotion, even encouraged him to seek it, stiffened his spine when he failed the test the first time. I was confused and did not know what to think because I liked the one who was promoted to detective very much and missed him when he stopped coming around. I thought the promotion was supposed to make him different. Why do it if it would not change you? But I was just a silly boy who did not know the world the way the cops did.

Cooper thought my mother pampered me too much, that I was just a mama’s boy, spoiled and privileged. I resented this as it impugned my manhood, such as it was at that time. It was important among these Black cops I was around to show myself a man, to be what they thought a man should be. I very much wanted their respect and I suppose I resented Cooper because, wounded as I was, I wanted his respect too. How could he say I was a mama’s boy, that I did not have the stuff of manhood in me?

I began earning my own money at the age of nine when I started selling shopping bags at the Italian Market on 9th Street. By age eleven, I was also working delivering the Philadelphia Inquirer in the neighborhood, (mostly to Italians, which I supposed made me a racial pioneer). This required that I had to get up every morning at 5:30 to do the route and get back in time to go to school. As our house was one of the few remaining that used coal heat, I had to maintain the fire during the fall and winter, which meant shaking down and removing the ashes every morning and getting the banked fire ignited to full strength again so my sisters and mother could clean up and prepare for their day. My sisters never came near the coal furnace; I remember they rarely ever came into the cellar at all. It was a boy’s job, as my mother said.

I hated it passionately, the fumes, the dust, shoveling out the ashes, and hauling the cans out to be picked up. Sometimes, my nose would be so clogged with coal dust I felt like a miner. It was a kind of adept’s art to put just enough coal on the banked fire to get it going and not to smother it completely. Re-starting up a dead furnace was tedious work, requiring skill to get the coals to catch fire from the paper and charcoal used to inflame them. My mastery of all of this was hit or miss at best but I felt I worked hard. But Cooper did not seem to appreciate any of this. “Your mother is always protecting you,” he would say. He did not appreciate those days when we ran out of coal how my mother would give me fifty cents to go the coal yard on Washington Avenue to buy a twenty-five-pound bag of coal to try to tide us over until she was paid and could order the delivery of a ton. (Delivery could be no less than a half-ton.) I would take my Radio Flyer wagon the five blocks to and from the coal yard to bring back the coal. One time the axle on the wagon broke and I had to carry the dirty bag of coal back in my arms. I was a small, thin boy, my arms were like pipe stems, and the twenty-five pounds felt as if I were carrying two hundred. I had to stop at every corner to rest a moment before I could continue. Despite the cold, I was drenched in sweat when I finally got home, and still I had my papers to deliver. Cooper did not appreciate anything I did. My mother did not either as she became almost uncontrollably angry that morning because I did such a poor job igniting the banked fire and filled the house with smoke. She called me “a miserable ass” and told me to get out of her sight, that I never did anything right. She had to fix the fire. It was on days like this that I thought she was on Cooper’s side, and that all Cooper wanted to do was to get my mother not to like me. (As a child, of course, I never thought about the enormous stress my mother endured or how tough her life was, how little money she had, how she had to thread the racial needle working and living among the Italians, how on that particular day, she had to get to work and to make sure my sisters and I got to school. I never knew what was on her mind. As a child, all my sympathy was for myself. For a child, the problems of adults are not real; indeed, adults themselves are not real but rather solipsistic projections of our young fears and hopes for the future and what we might turn out to be. They were also the fearsome masters at whose mercy and whim we were and for whom nothing mattered in our relationship with them except our neurotic obsession with being loved by them.)

Re-starting up a dead furnace was tedious work, requiring skill to get the coals to catch fire from the paper and charcoal used to inflame them. My mastery of all of this was hit or miss at best but I felt I worked hard. But Cooper did not seem to appreciate any of this. “Your mother is always protecting you,” he would say.

Being a policeman was not easy, especially a Black policeman. Cooper talked about some of the things he had seen people do to other people, how hard people made their own lives, and the lives of the people around them. He had a low opinion of human nature. As he told me once, he could not help it because he “saw people at their worst.” He had an uncanny ability to detect when someone was lying and, as he said, people lie all the time. It was the worst thing about people, he thought, how flagrantly dishonest they were and how unhappy most people truly are. I thought he would know this as he was unhappy himself. In some respects, I thought being a policeman made him unhappy.

In the late 1960s, when there were a lot of protests going on in Philadelphia, he was often assigned to sit on a bus parked in front of Girard College, a school that at that time was for White orphan boys, located in a section of north Philadelphia that had become entirely Black, as Black (and some liberal White) demonstrators marched around the school demanding that it integrate. He would occasionally emerge from the bus to spell one of the cops who had been working crowd control. My family supported these Girard College protests, and frequently attended them, “going to the wall,” as they called because the school was surrounded by a high wall. It was during one of these times that my sisters, now radicalized by their membership in SNCC and their organizing of Temple University’s Black Student Union, condemned Cooper for being a cop, “an oppressor of Black people” and told him he should join the protestors. At first, he looked at them as if he were amused, and then he shook his head and became sad.

“An oppressor of Black people?!” he said incredulously, “Why, as a cop, I’m the best friend poor Black folks got. Do you know how many calls I go on are when people get their electricity turned off or their gas turned off or their water turned off? I get calls from mothers who say their kids won’t go to school or their son has joined a gang. I get calls when couples are having disagreements, when somebody is playing music too loud, when people are cheating at a crap game, when some woman’s about to have a baby and needs to get to the hospital, when somebody’s got hurt out on the street. These aren’t crimes. I’m not beating anybody over the head or pulling out a gun. The folks have problems and the first thing they do is call a cop. You know why they call a cop? Because they know we will answer, because they know we will come to their neighborhood. The pizza man ain’t coming up here. The taxis won’t come up here. But the cops will come. I ain’t oppressed nobody in my whole life. All I’ve done is try to help people. And the people you think we’re oppressing call the cops because they think we can help ’em in some kind of way. They sure ain’t calling you Black militants to help ’em. You ask the poor black people and they gonna tell you they want more cops in the neighborhood. Go ahead and ask ’em. I know poor black folks a whole lot better than you do. All you militants want to do is make poor Black people over the way you think they ought to be, believing what you think they ought to believe. I don’t try to change nobody as a cop. I take people as they are, not like I wish ’em to be or think they ought to be. I leave people alone.” He shrugged and walked away from us. If I thought he never understood what kind of man I wanted to be or could be, I have always remembered this speech so vividly because he felt the younger generation of Blacks like my sisters did not understand the kind of Black man he was. He was right. He may not have been fond of me but he never tried to change me.

Cooper had his problems, a widower with four children and a girlfriend, my mother, who did not wish to be their mother. He had a brother who would eventually die from complications arising from a substance abuse problem. Cooper himself had a substance abuse problem for many years and that came close at times to getting kicked off the police force. When I wanted to feel superior to him I would just say to myself, “He’s nothing but a drunk.” But that was never really satisfying because, deep within myself, I did not want to feel superior to him. I wanted to learn something from him. And perhaps as my mother did not want to be the mother to his children, he did not want to be the father to hers and this might have hurt me deeply without my being fully aware of it.

… my sisters, now radicalized by their membership in SNCC and their organizing of Temple University’s Black Student Union, condemned Cooper for being a cop, “an oppressor of Black people” and told him he should join the protestors. At first, he looked at them as if he were amused, and then he shook his head and became sad.

Cooper taught me to drive my mother’s Volkswagen Beetle after she found herself too unnerved to do it herself every time the car made the sound as if I was stripping the gears. He was the best teacher I ever had, relaxed, patient, and always filling me with confidence, caring. When I would fail to take my foot off the clutch and press on the gas in proper measure and stall the car, he would tell me to ignore the annoyed drivers behind me. “They can go around you or they can wait. They can’t go through you. And they can’t move until you do. Don’t pay ‘em any mind. Just restart the car and let’s go. Now just ease off the clutch steady-like as you pump the gas. Just get a nice little rhythm with it, like a little dance step. A nice little rhythm.” And that was how it went. He never paid any attention when I accidentally ground the gears, when I made any sort of mistake. He never seemed nervous even when I almost had accidents. He would just tell me everything was all right and to keep on driving. He got me out of the habit of “riding the clutch” in order to prevent the car from stalling. “You control the car,” he would say, “It will do only what you tell it to do.” He so influenced me when he taught me to drive that when I taught my wife, Ida, to drive a standard transmission car I imitated everything he did, even his phrases and mannerisms. Ida thought I was a very good teacher. I have never taught that well again.

I had two deeply instructive conversations with Cooper. The first was when I was about twenty-one and a student at the University of Pennsylvania. It was around the time that my cousin, who was a few years younger, had been killed by a street gang. I was convinced that I would be killed the same way, not because I was in a street gang (such a good boy like me!) but because all manner of young Black men were killed on the streets and I was out on the streets all the time, walking around various parts of the city as if I had been injected with a wanderlust. I always walked with a purpose, a determined step, looked around me all the time. You had to be aware of yourself and your surroundings at all times. I liked traveling across the city this way, as if I were a sort of low-grade Woody Guthrie.

What brought this to a head for me was that within a span of six weeks I was robbed twice by street gang boys. The incidents were nearly identical. I would be walking when a young Black man, walking on the other side of the street and would cross over toward me, saying “Hey, don’t I know you from somewhere?” Another boy would follow him and, turning, I would see a boy walking up behind me. “You look like that boy that jacked up one of my homies last week. You look like one of them guys from 20th and Carpenter. That’s where you hang out?” I would of course deny all of this. I would tell them I was not a gang boy at all, that I was a student at Penn. “He’s a college boy,” one of the other boys would say. “He ain’t no banger. He got that book bag. He probably got some money ’cause he’s a college boy. How much money you got, college boy?” They would rifle through my pockets and take what little money I had. Then the first boy would say, “Yeah, we believe you, college boy. Looking at you close up now, I can see you ain’t the boy that jacked up my homey. But you best be careful walking around, college boy. ’Cause somebody could jack you up, kill your ass, thinking you somebody else. ’Cause you know college boys look like they could be gang boys. You know, we all niggers out here. And that would be a shame. You gettin’ killed on a humble and all. You know, a case of mistaken identity. It can happen.” And they would be gone.

He shrugged and walked away from us. If I thought he never understood what kind of man I wanted to be or could be, I have always remembered this speech so vividly because he felt the younger generation of blacks like my sisters did not understand the kind of black man he was. He was right. He may not have been fond of me but he never tried to change me.

Mistaken identity, perhaps the true scourge of the world, somebody thinking you are somebody else; you thinking you are one thing when you are truly another; you pretending to be one thing when you are truly another. Mistaken identity! After the second robbery, I went to Cooper and asked him to get me a gun. “I’m gonna die out here if I don’t get a gun. I need to protect myself. I can get my head blown off ’cause some gang boys think I did something to one of their boys.” I was nearly hysterical. I could see the skepticism on Cooper’s face. “I won’t really shoot anybody with it,” I pleaded. “I’ll just use it to make people back off. They won’t mess with me if they know I have a gun. I’ll get respect. I won’t get robbed and have these guys try to scare me. I can scare them with a gun.”

Cooper looked at me solemnly.

“Your mother would never forgive me if I got you a gun,” he said simply.

“She won’t forgive you if I wind up dead, if I die on a humble,” I cried.

“Look,” he continued, “if I give you a gun, one of three things will happen and they are all bad. One, you get stopped by the cops and they find you are carrying illegally a concealed deadly weapon. That’s an automatic three-to-five stretch in prison. And even if you somehow beat the rap, the cops will continue to pick you almost every time you step outside because you will have a record of being a Black boy carrying a deadly weapon. And they think the only thing a young man like you has a gun for is to commit a crime. Do you want to be harassed by the cops all the time? And having a gun gives them a perfect excuse to shoot you.

“Two, you get into an altercation or a threatening situation with some guy and you pull out the gun and shoot him. Turns out he does not have a gun and never really did anything to you except get smart or sound tough. Then, you’re gonna go to prison for shooting somebody you shouldn’t have shot, maybe for murder if you kill the guy.

“Three, you get into an altercation or something with somebody or somebody threatens you and you pull out the gun to scare ’em. Then, they pull out a gun and shoot you dead. Ain’t nothing gonna happen to that guy because you drew down on him with a deadly weapon. How was he supposed to know you weren’t gonna use it? When you pull a gun on somebody, you better be prepared to use it. You don’t draw no gun just to scare somebody.

“You’re better off without a gun. You’ll live longer. A gun will just give you a false sense of courage. Better to have fear than false courage. Fear will keep you alive. False courage will only get you killed out here. Them guys that robbed you could have killed you if they wanted to. They didn’t even hurt you. They just strong-armed robbed you. You just ashamed for that. They made you feel helpless. That’s all they wanted to do, make you ashamed and helpless, feel like a punk. They were just reminding you that you ain’t no white boy so don’t go wanderin’ around here like you think you are one. Don’t be no fool and get a gun.”

I never tried to get a gun from another source. Although I was angry at his refusal to help me, his words affected me profoundly. I lived in Philadelphia through most of the 1970s, the first wave of street gang slaughter, and survived just fine. Cooper was right: fear kept me alive. I was never even robbed again. I got smarter about moving around the city. And I stopped thinking I was Woody Guthrie. I was just a Black kid trying to grow into manhood, learning what life had to teach a Black kid like me about whatever kind of man the world would permit me to be but, contrarily, how I must struggle to make life accommodate the kind of man I wanted to be. So it goes with any person. Call the proper pace of this strife rhythm-a-ning.

The second important conversation took place perhaps a year or so after I graduated from Penn. I did not like the work I was doing: interviewing people who had been arrested to see if they could be released without paying a cash bail and substitute teaching for the Get Set Program, being around a lot of pre-school children. On a lark, I took the test for becoming a policeman and, a few weeks later, was informed that I was 82nd on the list. Usually, the first 150 finishers were selected to go on for further testing before being offered a slot in the police academy. I had rather settled in my mind that I would become a policeman. I felt I could do the job, that it was good, secure job, good benefits, good pension, and with my college education I felt I could move up the ranks quickly. When I told Cooper this, I thought he would be pleased, supportive, happy for me, that I was showing myself to be a man in the way he was. But in fact he looked almost grieved.

I was just a Black kid trying to grow into manhood, learning what life had to teach a Black kid like me about whatever kind of man the world would permit me to be but, contrarily, how I must struggle to make life accommodate the kind of man I wanted to be. So it goes with any person. Call the proper pace of this strife rhythm-a-ning.

“Why would you want to be a cop? That’s no job for you,” he nearly scowled. “That was good for Black men of my generation; becoming a cop was the way up, a good job for a Black man like me to have who had never been to college. But you can do a lot better than that now. You got a good education. You went to a good school. You can do better for yourself than being a cop. You don’t want to put up with the politics in the police department, the bullshit and everything. You owe it to yourself to make a better use of your education. As a Black man in the police department, you’ll just get frustrated after a while. I’d be disappointed if you became a cop. You’re a different Black man in a different generation.”

Then he grinned: “Besides, you don’t have the temperament for it. You’d make a lousy cop.” I never went for the round of psychological tests and background interviews. I decided to try to do a better thing or at least a different thing. I did the thing most people rarely do: I took someone’s advice.

Once, as a teenager, I came home from junior high school and, for some reason, I danced before Cooper. Some boys at school had been trying to teach me. He told me I was the worst dancer he had ever seen. I had no sense of rhythm. (Some piano teachers told me that as well.) I was injured by the bluntness of the criticism but Black men of his generation thought you were weak if you could not tolerate bluntness. “Don’t get addicted to praise. It’ll make you weak. It’s like somebody talkin’ baby talk to you all the time,” he said to me. In later years I came to appreciate what he said and my limitations as well, which I guess Cooper taught me about and about how being a man was something like understanding and accepting what you cannot do, not celebrating what you can. Life is an utterly exhausting design of drawbacks and inadequate, somewhat delusional compensations. Cooper taught me that in coming to grips with what I could not do, with what shamed me, that I would learn the valuable lesson that Black men of his generation instinctively knew: life was about losing but losing was a not bad thing. In fact, once you came to confront what you could not do, losing was the only thing that mattered if you learned to do it graciously and you did not let life trap you by wanting it to be more just because the only dumb thing human beings ever want is more. And there was another thing: when Cooper taught me to drive a stick-shift car, he was the only person ever to teach me how to do something rhythmically well, for I became very good at driving a standard transmission. I am forever grateful for that.