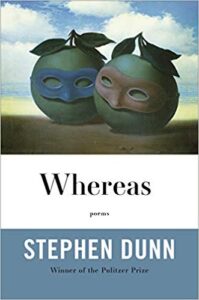

It would seem obvious that a new book of poems by a late-career poet is an occasion. Some poets develop and push themselves in forms and tones with every new book. Louise Gluck’s more recent books, for example, have been experiments in increasing a poem’s prose and novel-like qualities, even as her preoccupations with alienation and desire remain center stage. Other poets seem intent working in less obvious gradations of development, perfecting a style that seems adequate to all that their power of perceiving and feeling compels them to issue, or admit, to the world. This latter group includes Stephen Dunn.

Dunn is absolutely a poet who veers toward the public realm, a poet speaking to who he imagines might be listening.

Since the publication of his debut in 1974, Dunn has been praised for his plainness as compared to the more feverish poets of his generation, like Plath and Berryman. This plain-spokenness characterizes his work still. The critic David Orr makes a working distinction between private poets and public poets—the former make poems that are intensely felt but not always perfectly apparent (Plath) and the latter make poems that are the always apparent, using the clear and standardized language of the news (Yeats, most of Auden). The distinction quickly loses its usefulness (for instance, how do we come to terms with Auden’s poems that code queer desire so that only those who know know?), but Dunn is absolutely a poet who veers toward the public realm, a poet speaking to who he imagines might be listening.

Dunn is a poet of neat conceits. However much they tell of difficulty—marital disconnect, political outrage, language’s power to deceive—the poems in Whereas seldom inhabit the fierceness they confess to feeling or having felt, once. When Dunn does imaginatively inhabit a conceit, his work shines. “The Revolt of the Turtles,” for instance, follows the titular conceit to its logical consequences, giving the poem an off-kilter irrefutability. The poem begins as if in a world where turtles have been killed off:

On gray forgetful mornings like this

sea turtles would gather in the shallow waters

of the Gulf to discuss issues of self-presentation

and related concerns like, If there were a God

would he have a hard shell and a retractable head,

and whether speed on land

was of any important to a good swimmer.

This personification of turtles turns:

The oldest sea turtles among them knew

that whoever was in control of the stories

controlled all the should and should-nots.

Reframing the power of narrative as it plays into the question of liberation, the poem moves beyond mere serviceable charm:

But he wasn’t interested in punishment,

only ways in which power could bring about

fairness and decency. And when he finished speaking

in the now memorable and ever deepening

waters of the Gulf, all the sea turtles

began to chant Only Fairness, Only Decency.

This poem very simply and freshly has captured the dynamics of power. It has definitely digested its fair share of Foucault (whether or not Dunn has himself read Foucault is immaterial—the French critic’s ideas are in the air). What exactly is fairness, and what is decency, and who decides it, and how does that inform people or, in this case, turtles? The cries for Fairness and Decency have within them the premonition of their failure. Any new definition of decency implicitly defines who is indecent, and with such judgment comes a new form of control, of dictating morality. We can call this respectability politics in a turtle shell.

It would be misleading to describe these poems as modest pleasant dispatches from a weathered interior.

Of course, a poem’s power increases when it takes advantage of purposeful ambiguity. The poem’s ambiguity grants us the power to interpret the new chanting of Only Fairness, Only Decency, as pointing back more significantly to the power of the oldest sea turtle. The lineation allows us to see, for the breath’s worth of a line, that the turtle is speaking in a way that is “now memorable and ever-deepening.” Which may then point to this figure of the oldest sea turtle as a poet—memorability and ever-depth being the usual invoked ideals of the art.

The capaciousness of this poem is what makes other poems in the book somewhat irksome. In “The Invisible Man Blues,” the speaker yearns for a somewhat creepy omnipotence:

If I were invisible, I might want to inhabit

the privacies of certain rooms, hang around

before the bank closed, linger in a shower stall

until you disrobed. I could easily leave

any scene unseen.

Here, as a reader, I begin to pause—the only identity that can leave a scene “unseen” is the one considered unmarked, which, to my mind, speaks to whiteness. The title also of course must be reconciled with the Ralph Ellison novel and the black musical genre of the blues.

A song might begin,

sad, melodious, ours. It would say how unfair

the world could be to those who couldn’t hide.

It would say how lonely things can be

for those who can’t be seen.

This imagining of a song makes an obvious sense, given that the blues was borne out of the qualities he is describing. Dunn is appropriating the genre in order to pen a love song, to tell of how the song would be. Rather than just giving us a poem that takes advantage of lyric resources to be such a song, the poem resides in the domain of conceit-driven narrative. As a strategy, this beginning from a proposition is clearly a generative one for the poet (many poems in the collection begin out of similarly struck propositions). But this poem is indeed playing a game with us:

I’d no doubt start

to see the invisible everywhere—

walking the streets, sitting with others at meetings

and meals, spoken through, around, not to.

The song takes on grit, hurts the both of us,

but with luck I think I’ll forever hear it,

evidence of a privilege I’d no longer want.”

The poem seems to play with coming to an awareness of privilege—one of the most common words in use, these days, for indicating a recognition of where one falls in an intersectional analysis of race, class, gender, sexuality, and power. But as a poem, it does not seem to come to terms with the implications of its metaphor. The speaker seems to say that he no longer wants to be invisible—he wants to be seen, heard, talked to, understood, loved. Fair enough, as far as desires go, and the poem remains in the area of projection, of unfulfilled desire: I would no doubt start to see, I would no longer want. The poem’s interest in “grit,” in being “the slippery criminal” with the lover as an “accomplice,” however, speaks awkwardly to a recognizably coded subtext.

What are the anxieties of this body of work? Over and over Dunn’s poems speak to the anxiety of being in the wrong, of feeling certain instead of uncertain. The poem “In Order to Be True to Life” is marked by self-reproach: “A man / like you is always in danger of getting things / wrong.” (4). Dunn’s struggle with errancy proves adequate occasion for his poems. What does a person do with the desire to be right all the time, to forego the vulnerability of being proven wrong? In “Call Them In,” Dunn uses the artifice of persona to be so bold as to hold onto this stubbornness:

Call in

a sophist then, someone like myself,

who’d maintain for as long

as he could that he was right too.

Some truths are better than others,

which means, of course, some are worse.

What is the fundamental source of this adamancy? Or, if that question is too large, what is the source of this speaker’s adamancy? The speaker makes a call for a poet to appear:

Seems time to call in from the vast nowhere

some great adjudicator, some poet

who will arrive to hear both sides.

I have no agenda, he lies,

and proceeds to ask,

How many dead flowers

is anyone’s certainty worth to him?

In response to the poet, the speaker declares he would “sacrifice / not one flower but an entire garden for what I think I know.” The poem condemns the closed mind, and the poem that follows “Call Them In” is called “In the Land of Superstition,” which is an elegant way to complicate the argument. The various superstitions—from tossing salt over the shoulder to planting the long-lasting marigold in order to secure a lover’s attention—are enabling: “In this way / we create the world we want to live in, / wild, luminescent, a perpetual fiesta / with secret rules and a guest list made up / of people yet to earn their names.” That poem smartly makes a case—almost satirically—for how superstitious thinking excludes and is based on a false sense of safety; also, perhaps, how the wish for safety is false to begin with, if that is all we wish for and if we see no value in letting the true world in.

For Dunn, tied up with the question of poetry is the matter of justice—the sacrificing of an entire garden serving as a deliberately tepid example of the floweriness poetry can be (too easily) accused of serving only. An anxiety about poetry recurs throughout the book. Take the opening lines of “Propositions,” the poem that opens the book’s first (of three) sections:

Anyone who begins a sentence with, “In all honesty…”

is about to tell a lie. Anyone who says, “This is how I feel”

had better love form more than disclosure. Same for anyone

who thinks he thinks well because he had a thought.

The poem is concerned with standards—i.e. a poet knowing how to use form, how to write “a good sentence” (as opposed to a line?). This idea always seems troubling because it mistakes its own standards as desirable for everyone else. The tone sounds a little cranky and suggests even something about the idea that everyone should be able to speak Good English (to which we need to ask—who defines and enforces an idea of Good English—what constitutes Bad English?). Again, I find myself uneasy with the implications of his comparisons. Which the poet does not intend, it seems, as he is trying to connect good writing to good loving:

Before I asked my wife to marry me, I told her

I’d never be fully honest. No one, she said,

had ever said that to her. I was trying

to be radically honest, I said, but in fact

had another motive. A claim without a “but” in it

is, at best, only half true. In all honesty,

I was asking in advance to be forgiven.

Fidelity to good sentence-making, fidelity to the beloved; fidelity to radical honesty. The poem’s title guarantees that its declarations remain propositions, but we do read the declarative statements as declarative. The gap between the proposition and the revealed truth is intended to create a wispy pathos, but the poem remains, to my view, marked by its desire to set-itself apart, seeing itself as superior in writing and thinking. The declaration of “radical honesty” is designed to serve as a truth, and it does, but it remains ill hitched.

In his best poems, Dunn becomes an American version of the great Polish writer Wisława Szymborska—whose poems exhibit a similar charming rendition of conceit and narrative, inflected always by a nimble practical intelligence. “Whereas the Animal I Cannot Help But Be” is as elegant a send-up of the human as exists in this collection, with its affable apt depiction of a possum that “knows how to play himself,” of bats that “at top speed merely glance / off of what they disturb,” of moles and cats, and in a surprising erotic image—“the earthworm, / straightforward but slippery, both ends open, / getting under the feet of barefoot girls.” The final stanza is worth quoting in its entirety:

Whereas the animal I cannot help but be,

duplicitous, having more than once been taken

to task, shamed, still envies the silver fox,

leaving a false trail, swerving this way, then that.

The poem exhibits Dunn’s signature reliance on a conceit—in this case, a wry invocation of several animals worthy of praise—and achieves an elegant mystery, wherein he has put himself as a living human-like actor in the scene (rather than an audience member or the wise voice-over.) The silver fox is the poet—one whose false trail is seductive, swerving this way, then that—with a wry pun on the expression where an attractive gray-haired older man is compared to that animal.

Many of the poems here exhibit an awareness of themselves as aesthetic objects. The way these poems understand themselves as poems never breaks their surface, however—there is always a grounded scene, a discernible speaking subject, and clear imagery and colloquial syntax. The turns to poetry as a topic ring of a kind of somewhat worn spinning:

Let’s say you think of it as your job to cast

a light on some of the empty spaces left by the gods.

What’s a poet anyway but someone who gives

the unnamed a name? A see-er more than a seer,

a maker of what becomes obvious, that’s been there

all along. What you unearth resembles,

you hope, the real. You want that boy

who used to read under the covers by flashlight

to once again be astonished.

Once again he is. Suddenly there’s this country

of no longer hidden things, this other world

both of you are walking toward.

It is not surprising to think of poets as namers—it is common enough to encounter Adam from Genesis as the first poet, since he named, for instance, all the animals. What the poem here does do is expose a longing and verify an ambition—to suggest that the poet and the reader both move towards “this other world” of “no longer hidden things.” The poem throws itself into relief against a world where the gods are dead. Casting your lot, as a poet, among references to an ancient past extends the line of credibility and makes a claim for a connection to a long-standing lineage. The question becomes whether or not this classical turning feels fresh.

For Dunn, tied up with the question of poetry is the matter of justice—the sacrificing of an entire garden serving as a deliberately tepid example of the floweriness poetry can be (too easily) accused of serving only.

To my mind, Dunn more or less meets the bar he has set for himself—the question then becomes how a reader comes to terms with a poet who seems content with the strategies and forms he has cultivated for himself. It would be misleading to describe these poems as modest pleasant dispatches from a weathered interior. As seen in “The Revolt of the Turtles” and other poems in the collection, the ghost of political catastrophe haunts these poems. The poet’s ambition here is ample, as seen in the poem “In Order to Be True to Life”:

It’s possible to rethink that reddish full moon

coming toward you across the bay,

to change even the feel of it as it approaches.

That is, if you want to be true to life,

not entirely to the one you live.

This is another way of articulating the vision of poetry—to tell the largest truths possible. And yet how this poet understands social difference–ability, sexuality, race, etc—remains at times underdeveloped. While the poet is firmly against “rapturous solutions in the offing,” he still believes—as perhaps he is right to—that what he needs to understand is “the mystery / every family harbors.” It is an interesting question to think about as readers and writers—what is the dream of a common language really about?