“We’re all born bald, baby.”

—Telly Savalas

My first noticeable symptom, I guess, was the start of a tonsure in my 30s. I do not look in mirrors much, and the thinning was not visible to me at that angle anyway, so as far as I knew, I looked like Fabio, the poster boy for romance-cover hair in that era, and sailed through life unburdened.

(All right, I might have been a little concerned, having watched the musical Hair at the age of sixteen. There was an awful lot of emphasis on hair in that musical. But popular styles have backed my lack of choice in the matter.)

Confidence and good humor are more important than hair, and even with other deficits in my physiognomy—also not apparent to me face-on in a mirror—I did not have trouble finding partners and friends, getting work, or feeding myself. The front loader does not know that it does not look like a Ferrari; it just does its job. I have served most of the standard roles—laborer, soldier, helpmate, procreator, even crude philosopher—in ignorance that my skin was showing.

By the time pattern baldness crept into the area some men comb-over, and my temples had receded, I not only did not care, I thought of my hair about as much as I wished my legs had grown an inch longer.

I will go a step further: I have thought of myself as fortunate when it comes to hair, because mine takes so little maintenance.

We were on vacation in South Florida when I finally decided I was sick of oily hair in the heat. I had a strange barber shear me, exploratorily, leaving my hair long enough to pull. The timid half-step was ridiculous. I looked like a ‘cruit again, two months out of basic training, so as soon as we got home I had it taken down to stubble, where I have maintained it for eighteen years. My friends and children tell me, generously, that if I had to go bald I got lucky because my skull has a pleasing shape.

(My sons ask why I do not shave my head, but in truth the thought of a razor on my scalp makes me queasy, for some reason shaving my face does not. Maybe it is the hammock of blood vessels just under the skin, some ropelike, which make head wounds look so much worse than they are.)

I will go a step further: I have thought of myself as fortunate when it comes to hair, because mine takes so little maintenance. (An old friend foreshadowed this by saying for years that he was relieved to go bald, because all he had to do in the morning was wipe his head down with a washcloth, and he was ready to go.) I also have an aesthetically-pleasing amount of hair on my chest, none on my back, and I cannot grow a decent beard or moustache. The hair on my upper lip has no pigment and is nearly invisible. I shave my face two or three times a week and use a $20 Walmart clipper on my head twice a month. With the money I have saved on professional haircuts and disposable razors over the years I could have bought a Miata convertible and had a proper midlife crisis. Sadly, I wasted it on books.

• • •

“If you’re bald, is your whole head a forehead?”

—My younger son, roasting me, but with his own concerns

Folk wisdom says we inherit pattern baldness from our mother’s father. In reality, some 200 genes from both sides combine differently, even in the children of one family, to predispose someone to pattern baldness or not. One possible mechanism is a sensitivity to DHT (dihydrotestosterone), a hormone made from the body’s testosterone, which weakens hair follicles.

If baldness is a visitation, it is not of the sins of the father, and it is not particularly selective. Before age fifty the majority of men are bald or balding, and 40 percent of women have noticeable thinning. There are also the other unbidden baldnesses, such as from chemotherapy or alopecia (thought to be an autoimmune disorder).

Perhaps because baldness has been impossible to control for most of human history, it is often used to make a point in forced control, by shaving convicts and military recruits. Symbolically, this demeans and strips personalities from individuals; medically, it makes hygiene and treatment of lice easier; security-wise, it means prisoners cannot hide drugs or weapons in their hair. (The idea, attributed to Alexander, of not having hair for the enemy to grab in battle is mostly moot for the U.S. military, which uses technology to ensure it rarely fights hand-to-hand.)

If baldness is a visitation, it is not of the sins of the father, and it is not particularly selective.

Non-medical baldness is about showing who or what is in charge. Some people, such as Sinead O’Connor, shave their heads to take charge of one aspect of their own lives and to deny others that chance. On the other hand, monastic tonsures and full head-shaving at ordinations are common symbols of surrendering-to.

• • •

“Here is a man without any hair. He suggests nothing.”

—Caption to an illustration said to be from the Daily Mirror (England), January 22, 1909

But there are as many ways of thinking about baldness as there are heads. We are a vanity culture, and the attention devoted to interpreting appearances reaches mystical levels, like phrenologists labeling porcelain skulls for qualities such as “amativeness, philoprogenitiveness, concentrativeness, adhesiveness, combativeness, destructiveness, secretiveness, acquisitiveness, constructiveness, self-esteem, love of approbation, cautiousness, benevolence, veneration, conscientiousness, firmness, hope, wonder, ideality, wit, imitativeness, individuality, form perception, size perception, weight perception, colour perception, locality perception, number perception, order perception, memory of things, time perception, tune perception, linguistic perception, comparative understanding, and metaphysical spirit.”

The interpretation of some aspects of the body tends to be more settled. Bad teeth, for instance, are rarely admired. But baldness has a strange way of serving equal and opposite interpretations. It can be seen as emasculating or hypermasculine. Women think bald men are sexy; women hate baldness. Some people see the bald as victims of fate; others think the bald have taken control of their destinies and made the most of the situation, without pretensions or the lies of the wig.

Baldness as a look is mostly about the absence of adornment, the negation of complexity. This does not mean it is innocent. The neo-Nazi skinhead movement cast a pall on baldness for two decades. But these days it is more closely associated with sports figures and actors than with white supremacists, who have gone the route of Richard B. Spencer (with his vaguely Nazi-ish haircut called the “fashy”) or whatever that ‘do is that is worn by white dudes who fetishize Vikings.

• • •

“I’d say my fashion or beauty tip is to take the thing about you that makes you most distinctive and then exaggerate it. So if you have a little bushy unibrow, make it a dramatic unibrow. If you’re balding, go completely bald.”

—Sasha Velour, American drag queen

For me, baldness is not exactly an aesthetic, but it does serve my interest in being more intentional, less egotistical, and less wasteful. I try to stay in decent shape and wear simple clothes and shoes I can walk miles in, at any time. After I have spent long periods finishing a project, I get myself cleaned up, cut my hair, and rededicate myself to movement-readiness and utility to others. Baldness fits with that. It is the (non)style I can wear to go do anything in the world without stopping at the salon first.

But the way I look often has unintended effects. A few years ago I went camping and had to carry my old army duffel through the airport and train system. By their looks, comments, and offers to buy me cups of coffee, others seemed to mistake me for some disgraced Special Forces major who had refused to retire and could not afford a baggage handler or taxi.

Bad teeth, for instance, are rarely admired. But baldness has a strange way of serving equal and opposite interpretations. It can be seen as emasculating or hypermasculine.

Once, at a reading from one of my books, I chose my combination of pieces poorly, leaving me to revisit the emotions of the deaths of my mother and my father. Near the end I wept. Afterward, my boss said he had thought I was hard and waved his hand up and down to indicate my head-to-toe appearance. It took me aback. I had never thought of myself as hard, and certainly never said that, but I began to realize that I might be, just not in any way he could understand.

My baldness is not meant to signify anything, but it does not mean nothing, even to me.

• • •

“I mean, I guess he would be okay if he did something with his hair.”

—Kelly Kapoor, in The Office, looking at a photo of a bald man

The two men who figure most prominently in my known family history were both bald. My maternal grandfather died 15 years before I was born, and my father left the family shortly after I was born, but they were the two men my mother, who raised me, gave the most emotional attention with her stories. (I know almost nothing of her mother, except her final years.)

My mother adored her father, and I cannot remember her mentioning his baldness, except maybe to say it complemented his kind eyes, dimpled chin, and kind heart. He was, she said, a commanding and dignified man.

My mother had grown to hate my father, in part for his leaving, though she would have hated him if he stayed. She denigrated his appearance to me every chance she got, starting with his baldness, and how much he looked like the dour farmer in the painting American Gothic by Grant Wood. (In photos from the unhappy, haggard period after my father left us, with the right pair of glasses, he did look like the man in that painting.) Her anger was unfortunate, because I grew to look more like him and, she said, to act like him sometimes.

I was concerned.

• • •

“Here we have a baby. It is composed of a bald head and a pair of lungs.”

—Eugene Field

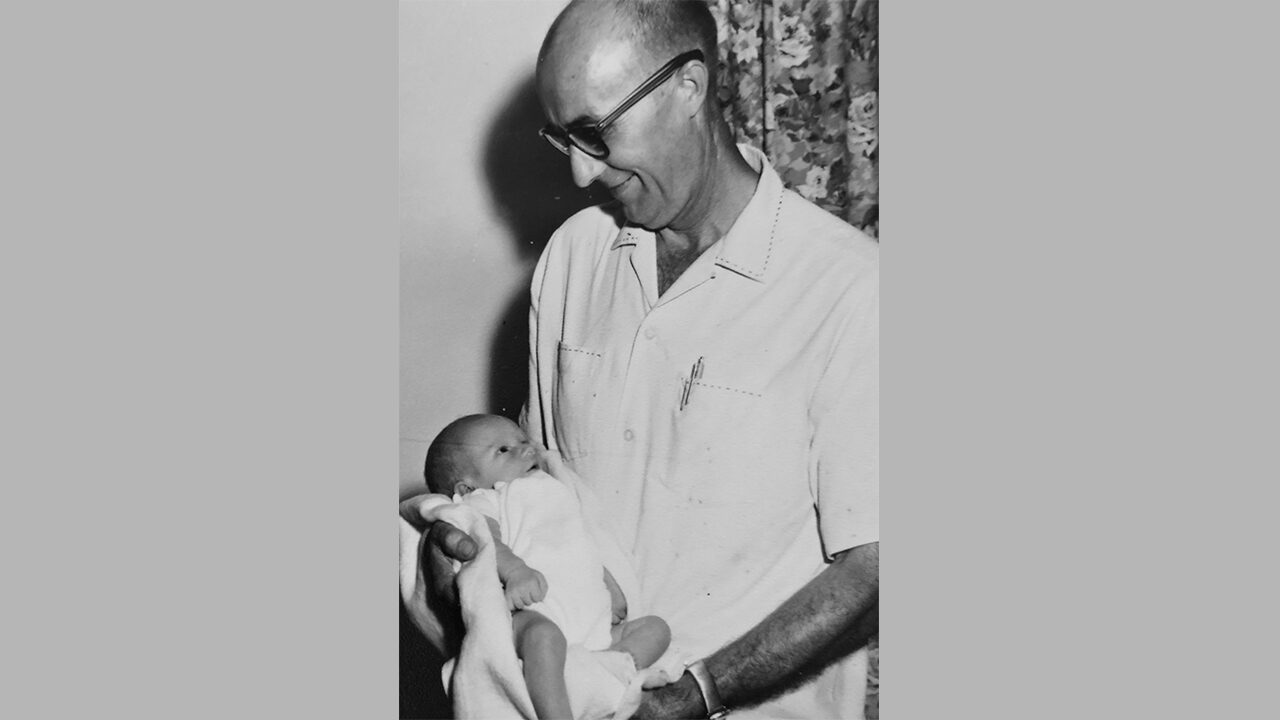

The photo at the top of this piece is of my father holding me, in Saigon, shortly after I was born. I used it for the cover of my book Pirates You Don’t Know, which contains the essays about my parents’ deaths and has a motif of the distances between people, even when they are alive.

My father is bald, dressed in a simple guayabera-style shirt, and he wears a sturdy watch. There is a pen in his pocket, which of course I find significant. Despite the big day, he is ready to go to work, to go anywhere in the world. Soon, he will. His smile is proud but stiff. His hold on me, and his stance, are those of a hard man trying to be gentle.

I am bald too, having been born at an early age. My arm is braced, chin tucked, and I have raised my eyes to meet his gaze, not entirely innocently. We share a look, there in the clinique. We share two names and up to 50 percent of my genes. Even friends have thought the image is me with one of my sons.

• • •

“You can inherit male-pattern baldness from your mother’s father, but not a tendency to fight in the First World War.”

—Comedian Jeremy Hardy

One of my sons suggested recently that I put photos of my father and me, from our respective military service, head-to-head on the bookshelf.

In his official Army photo, taken about seventy years ago, my father is grinning and handsome. He is maybe thirty-two years old and has survived enlisted service in the Pacific Theater in WWII, gotten his bachelor’s degree, and been made an officer. The photo is black-and-white, so I cannot tell if he is a first or second lieutenant, but the seams of his garrison cap, sometimes called a cunt cap, glisten with gold or silver thread. The cap sits at a cocky angle.

He wears a dress jacket with his Armored badge on the lapel. His tie has a perfect dimple and bulges out, like a cravat. He has perfect teeth and a straight nose and looks straight into the camera, his right eye soft, even dreamy, his left sharp and aware.

He is headed for a successful career in teaching, administration, and consulting and will prosper in parallel with America’s postwar boom. He will not be paying for my upkeep, or medical bills, or college. He will pass away peacefully after a long and comfortable retirement in gated communities, without running out of money before he dies or seeing our country’s most recent problems. (He told me democracies eventually run to fascism.)

My official Army photo is what is called a morgue photo, taken on one of the first days of basic, in case you are killed in training. I am further from the camera, so I look smaller than my father does in his photo. My shirt is a fake half-shirt put on every recruit in turn, like a poncho, and is grimy and wrinkled. I am 19 and have no rank or other insignia, because I have not earned any. A U.S. flag with complicated tassels looms over my right shoulder. The bored photographer made me look up and sideways in its general direction, as if it is my date in a prom picture. I could not afford prom, and I am in the army because I have no home or prospects.

There was a time I might have looked at these photos and felt sorry for my younger self, especially in comparison to my father. Now I see other things hidden in my face and am proud they were revealed in time. I look at his young face and think, Fuck that guy. Let’s go.

Most of my life I have wondered what kind of man my father was, and what kind I could be. Late in his life, when I reconnected, he was a handsome old man with a spark in his eyes, active and well-read. His early life, son of a sharecropper in the Depression, was hard. We had the same politics and had been to many of the same places. Since then I have done what I could with the scant knowledge from our acquaintance, but the older I get the more I question what is important in stories. Narrative inheritances are often as badly jumbled as genetic ones, and there is so much we do not know, beyond surface appearances.

Now my sons look at me. They look at their mother. They wonder about their futures and try to guess at the pride and shame hidden in the histories of their relatives on both sides. What they can know is that they are free to sail their own courses, without having to see themselves from every angle first. They will, to a great extent, become the people they hope and work to be.