At the behest of my editor, an author’s statement:

In June 1922 a “massacre” occurred of nonunion workers at a strip mine outside my hometown in Southern Illinois, which for a time became known in the media as “the black spot of the nation” and “the most radical community in America.” I had a personal connection to the event: my maternal grandfather was the president of the local UMWA subdistrict, and a state senator, who lived in that town.

Though he was away for the state constitutional convention at the time, he telegrammed the relatively-new president of the national UMWA, John L. Lewis, to ask what should be done about the nonunion men loading coal during the national strike. Lewis infamously replied that local miners “are justified in treating this crowd as an outlaw organization and in viewing its members in the same light as they do any other common strikebreakers.” This is seen as a precipitating event in the violence to follow, in which twenty-three men died.

My first two books, the novel A Democracy of Ghosts and the narrative nonfiction Herrin: The Brief History of an Infamous American City, portray (fictionally) or explain (historically) what happened.

I was invited recently by my hometown library to present on my little narrative nonfiction book. What follows is neither about the historical event nor what I actually said in my talk; it is about the feeling of presenting a slide show to an interested and supportive crowd after being out of that game for several years. It is about what happens in the mind when a writer has published perhaps two million words and the focus of ambition shifts to narrative instability itself—to what the topic really is, after all.

• • •

Time is short, material long, so let me begin. I feel as if I am balancing in my shoes. Do not say that. Good afternoon. My topic will be “finding balance.”

This is me thanking you for inviting me to speak today. It is great to see so many of you here. My pleasure is genuine, but that means nothing if I am not seen as genuine. Here is my genuine smile, my open hands. I admit I do not know why you came out—do not admit that—since the little book I wrote with a chapter on the event that took place outside our hometown is a dozen years old, and I no longer remember historical particulars. If you have questions about your relatives’ role in the event, please reference the index of surnames in the Japanese scholar’s dissertation listed in my bibliography.

Another thing I would like the chance not to say is that while my research about the events preceding the event, the event, and the events following the event will always serve as part to the whole of my understanding of certain passions and my beliefs about human dignity and agency, I used my writing of them to reach other topics that better serve my own wonder at the experience of being alive. I will not ask if you think all writing is mere injunction and reassurance for the self. But don’t you think so? We make sandcastles together in the liminal space between us but retreat to our own homes at nightfall, and the tide will likely obliterate our pleasant labors.

My topic today will be “the difficulties of communion.”

I pause now, standing with you, in this library, in this town, because I sense, in some synesthetic way, crystalline structures of perception and memory growing out on both sides of me. I am already picking among them, finding treasures and holding them to the light, as I did when my Uncle Paul used to take me to the dump on the edge of town, and I dug around and found miracles. One was a box-kite, nearly the size of a refrigerator, just balsa sticks glued together with wood glue with butcher-paper skin; somehow the bulldozers had not crushed it. It pulled so powerfully in the sky that no small boy dared tether himself to it, and even now it lifts: who in that time and place made such a beautiful fallen thing?

We make sandcastles together in the liminal space between us but retreat to our own homes at nightfall, and the tide will likely obliterate our pleasant labors.

Continue to talk but on topic now. My topic: “fallen angels.”

Paul’s brother was taken by the Japanese, as they used to say, and came back changed, snow-white hair and gauntness the least of it. Some loss of self and its connections to the world, so even the experiences of years before the war were left without organizing principle. How to overcome events? This man, by attentiveness and kindness as muscular as any blacksmith’s blow, forged somehow a deeper love of life after that event.

So this will be our topic: “the death of loss, waste, and calumny.”

First slide, please.

This was the little house where I grew up, situated halfway between the school and the cemetery. If that’s not a metaphor! My body still remembers waking from a sweaty nap in a cloth diaper on a bed in that house, after nearly sixty years. I thought the future came in through the windows then.

My topic here today is “promises.”

The road past the house is the one on which they marched those nonunion men during the last hours of the event. Having abused them at the schoolyard, they would torture and murder them, tied by their necks, at the cemetery. I never knew that until I was years gone from that house.

I pause now, standing with you, in this library, in this town, because I sense, in some synesthetic way, crystalline structures of perception and memory growing out on both sides of me.

My topic is “condemnations of history we try to overturn with cheerful stupidity.”

This is me having a wonderful childhood in our backyard, making a snowman as a tyke, then being afraid of it. Pause for laughter. None, that’s okay.

This is the headless horseman I made by stuffing fallen leaves in my own clothes and putting the dummy—making me the dummy in a sense, you understand—on a discarded rocking horse from the dump. Pause for more laughter. More none.

This is…well, whatever this is—confidence slipping, but do not say that—me dressed as Count Vronsky, it seems, maybe age eight, with my beloved cat who climbed trees to sit with me in the branches as I read. Good-humored irony about one’s own bookishness. Really thought there would be laughter there.

This is me, pre-puberty handsome and laughing, writing in a journal under the tree on the schoolyard where they abused those men, some of them veterans of WWI. The homes of two of my childhood best friends, and the church where my mother used to be the secretary, are down the road by the woods where they hung that other man and hunted others during the event. Farther on is the dump, where they made the first group of men from the mine run an armed gauntlet with small chance of escaping through barbed wire. These were our bucolic playgrounds of buckthorn and dust, where we ate tiny, sweet blackberries from brambles grown in blood.

That is my topic today: “How love, experience, history, a belief in the future and in connection, in reading and writing, not only formed my personality but also created a platform, stable even in pain, from which to see the world including this town.”

This is my Kodachrome mother, buried now in the cemetery, who was from here and shaped by it too. She is dressed as a Cub Scout den mother and shows off a second-place ribbon from the parade past Lincoln’s tomb. It was her sister, a wild woman who once accidentally drove the wrong way up a busy highway, who, as drivers honked and swerved to save her silly life, shook her fist out the window and shouted she was from this town. Ah, laughter at last; the seal broken.

The road past the house is the one on which they marched those nonunion men during the last hours of the event. Having abused them at the schoolyard, they would torture and murder them, tied by their necks, at the cemetery. I never knew that until I was years gone from that house.

This gives us my topic: “What it means to carry around the legacy of this town, especially when the event actually happened mostly outside town and its participants were from all over the region.” Or: “What did I ever do?”

This is my mama’s and aunt’s Daddy, a politician and labor leader who played an important role in the event, which he no doubt had to struggle with in reputation thereafter. I have only three photos of him, which by advancing age descend my staircase at home. Should they ascend instead?

This is my topic: “How to remember the dead, when most were rascals?”

I have come to my own conclusions about the meaning of the event, and using the narratory and rhetorical tricks of a writer and former teacher I may temporarily make you think you agree. But I stand here filled with distrust of stories in general, having waded through so many of them. It is a time of strong beliefs in shallow stories. Thank you for nodding, first cousin on my mother’s side.

Story’s hooks—cause and effect, motives, settled outcomes, sensory details, the irony that knows better—at best pluck selectively from the sea of reality.

These were our bucolic playgrounds of buckthorn and dust, where we ate tiny, sweet blackberries from brambles grown in blood.

Story is attachment, an investment in certain resources, and while it is good to see you, imagine what might be said if this talk was for no one and nothing—silent. We know what Plato said about rhetoric, and poetry. But we must be left something for our future.

My topic today, if I get to it, will be “inheritance”—historical, emotional, existential—and “inheritance denied.”

Our first inheritance is the earth herself. This region was once a tropical swamp, fed by an ancient river bigger than the Mississippi. The swamp had ideal conditions for the growth of riotous vegetation, which fertilized more growth.

This is the path of that river.

This is the map of the Quality Circle of coal, which as you can see conforms to the outline of the final bend of that river before it drained past the swamp to the sea. Millions of generations of plants thrived and died under the sun, were capped by shale sediment flowing off the Appalachians, became peat, and then relatively low-sulfur, bituminous coal in shallowly-buried seams a dozen feet thick. It created the basis for an extractive economy, as it is called, though for a few years miners’ meager pay led to the “silk-shirt days,” a criticism of the working class, who were mostly trying to raise families, buy homes, and save a few bucks in the new banks.

These are photos of packed streets in town, booming shops, the electric-trolley interurban line, the saltwater pool and dance hall that hosted Duke Ellington and the Dorseys.

This is the cover of an issue of The Masses from 1914, showing a miner firing his gun at the Colorado National Guard and John D. Rockefeller’s Colorado Fuel & Iron Company camp guards, after his wife and children were massacred in their tent community in Ludlow.

These are striking miners after the Battle of Blair Mountain, West Virginia, in 1921, turning in their long guns to federal troops after fighting the corporate armies abusing them.

This is a wrecked Bucyrus steam shovel, said to be used to help dig the Panama Canal, at the mine outside our town that caused the event now named for our town. A miner in town was heard to say, as the violence grew, “We must show the world this ain’t West Virginia.”

My topic is “the Erinnyes, and how the spirit of violence spawns violence.”

This is the old #2 mine in town, after a coal depression followed by global economic depression.

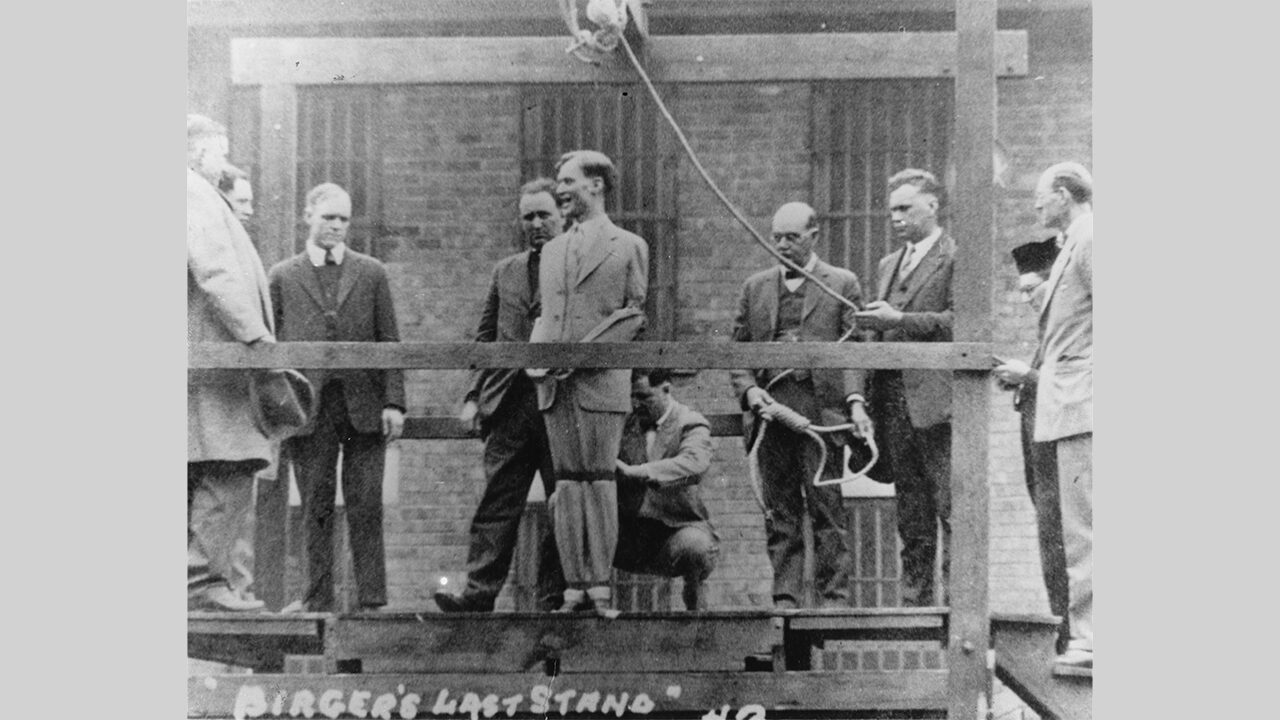

This is the Birger gang, brandishing shotguns and Thompsons, who flourished in the years after the event, a time of wet/dry warfare, the Klan, and a fascist lawman who took over our town.

This is Charlie Birger, smiling cheerfully, on the gallows. He was born an Adygean Jew and improbably became one of the main rascals of the period. It was reported he turned down the customary injection of narcotics for the condemned, in favor of his own reefer.

“It is a beautiful world,” he is saying to the crowd, just before the hangman slips the hood over his head.

Our topic is “dark comedy.”

This is a CCC camp, like the one my father served in as a teen, to help explain the role of the New Deal and WWII in keeping the region from starving to death, no matter your view now of “big government.”

This is going swimmingly.

This is the black-and-white assembly line at the factory in town that made washing machines. Despite excellent film and the photojournalist’s skill, the gleaming chiaroscuro of metal does not capture the story of working there. My mother worked there in her golden years, after marriage, family, and teaching job ended. Money she earned there was found, after we moved her to a nursing home, in a Bunny Bread sack in a stocking drawer in her bedroom; after her death it helped me go back to school and restart my life. Again.

The topic of this talk has been “metamorphosis.” Thank you again for coming.

Wrapping up now, accelerating. This is a float on Park Avenue during a parade for the diamond jubilee of this town. What started as a bell-shaped prairie in the nineteenth century became a small city with the hope, as the Turk in Candide says, that “labour preserves us from three great evils: weariness, vice, and want.”

This is Charlie Birger, smiling cheerfully, on the gallows. He was born an Adygean Jew and improbably became one of the main rascals of the period. It was reported he turned down the customary injection of narcotics for the condemned, in favor of his own reefer.

The topic of today’s presentation has been “optimism and its discontents.” Do not say that. Lighten things up at the end.

This is me, at age twenty-two, in an Army diver’s dry suit, holding a Kirby Morgan SuperLite 17B hardhat, with rusted girders and a work truck in the background. It might seem a bid for proof that I have been out there, doing things that would match the authenticity of staying here, but my intent is “hometown boy has had the great good luck to remain alive, when so many were not given the chance.”

Finally: this is a clipping from a regional newspaper that shows me, age three, with my mother in this very library. I am described as the town’s little reading tiger, which is undercut by the explanation that I cannot read.

That topic is “fake news.”

If I could go back in time and speak to the audience of myself, sitting a few feet away in this library, my topic would be “joys of the future”: The freedom of long summers and physical distances measured by bicycle; days at friends’ houses; games of horseback tag; dirt bikes and BB guns in the strip mines; a large family to be treasured because it will not last long. Then helicopters, the sea, walking as punishment and pleasure. Loves, sex, children, friendship, nature, food, travel, art, adventure, work. More books, many of which I can read. Pay attention. Write some of it down, I would say. I will find it later.

But the topic of this talk, today, with you, has been “finding significance.” This is a monstrous, lifelong, sometimes joyous task, and my only credential for being here at all is that I have spent my often joyous, monstrous life so far at that task and have come back to the source of that search. Thank you for (still) being here, which today means the world. Say that.