Part one of this essay appears here.

You have never chosen to know us. You have only come to us to confront and conquer us. And it is this tendency to continually pervert the experiences of life that you have passed on to the federal government that has created our present difficulty.

—Vine Deloria, Jr.¹

Wes Clark Jr. had his own problems in the wee hours—“the craziest part,” he told me later. He said after the easement was announced, “I get a text from JR American Horse [a prominent Lakota elder], telling me something to the effect of, ‘Now I know how Sitting Bull felt when he was ambushed in December.’

“And I was like, ‘Holy shit, that’s a really hostile text. What the heck did I do?’”

Clark said there had been rumors of weapons caches in the camp, and “supposedly IEDs, and somebody talked about a U-Haul full of a ton of alcohol to make Molotov cocktails, and we spent all day Friday and Saturday running down these rumors….” He said all the camps, including Red Warrior’s, were searched and no weapons were found, but Loreal Black Shawl, the headsmen, and others “confiscated all of JR American Horse’s supply depot and kicked him out of camp.”

“Nobody told me any of this happened, and as I’m walking to the back gate [at 2:30 in the morning], it’s dark and there’s a traffic jam at the back gate to get out, and…the guy running our TOC comes up to me, and goes, ‘Dude, you’re about to get shot, get the fuck out of here,’ so I was like, ‘I’m gone, dude.’ I took off that white poncho I was wearing, pulled up a hood over my head, went out to [a vet’s] yurt. He loaned me his plates, gave me his little coagulator in case I got shot. I rolled out onto the barbed wire, and I walked on the road back towards the casino.”

Clark said there had been rumors of weapons caches in the camp, and “supposedly IEDs, and somebody talked about a U-Haul full of a ton of alcohol to make Molotov cocktails, and we spent all day Friday and Saturday running down these rumors….”

“So I’m walking on a dark road, heading to the casino for fifteen or twenty minutes, until one of my dudes with an SUV gets through the traffic jam and gets out. And then they’re like, ‘No, no, everybody says you should head back.’

“There’s weird drama, I guess, because a lot of the Native dudes I’m with are like, ‘Reservation life, man.’ People get into weird feuds with each other, so best to err on the side of caution.”

Susan Abulhawa wrote at Veterans Today:

“At one point, Wesley Clark tweeted that mercenaries from Gulf States were hiding in the casino to assassinate him. That tweet elicited a collective eye roll at Fort Yates. ‘He’s probably drunk,’ someone said. But later, in a letter of apology for the ‘errors in [his] attempt at leadership,’ Wesley Clark assured the vets that he drank no alcohol, but was rather very sleep deprived as he spent inordinate time ‘in a diplomatic role between the multiple factions and interests.’”

• • •

Fall 2016 in North Dakota was unseasonably warm. Laurel Vermillion, president of Sitting Bull College, said, “This is the Creator’s way of showing his support.”

When a blizzard descended the morning of Monday, December 5, some saw that too as providence celebrating the victory and punishing the police, who they believed could not take winter as well as Native Americans could.

Standing Rock Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault spread the word that it was the wish of the tribal council, the Cannon Ball district, and the tribal elders that everyone leave the camps, which had become a danger in the bad weather and a burden on tribal resources. This was not welcome news to all.

“Maybe the biggest problem really was that we won just by showing up, and a lot of people wanted to do something, and it wasn’t sitting in a blizzard,” Michael Wood told The Young Turks later. “It was to do some kind of action. I think there’s a good bit of, ‘Hey, the blizzard hit us, we weren’t ready for that, and we didn’t get to do anything very exciting because we got snowed in.’”

As Oceti got slammed, Wes Clark, with a dozen hastily-assembled vets, was in an auditorium at the casino, facing Leonard Crow Dog, Phyllis Young, and other elders, surrounded by hundreds of people. Crow Dog, the Oglala Lakota spiritual leader of the American Indian Movement, from its founding with Dennis Banks through Wounded Knee and beyond, sat gravely, with dignity, in his wheelchair.

“We came. We fought you. We took your land,” Wes Clark said. He was dressed in his cavalry officer’s uniform. His face looked like it might melt off with piety. “We signed treaties that we broke. We stole minerals from your sacred hills. We blasted the faces of our presidents onto your sacred mountain. And we took still more land. And then we took your children. And then we tried to take your language. We tried to eliminate your language that God gave you and the Creator gave you. We didn’t respect you. We polluted your Earth. We’ve hurt you in so many ways. And we have come to say that we are sorry.”

He and the others behind him knelt, suddenly. “We are at your service and we beg for your forgiveness,” he said, choking on the last of it.

Wes Clark Jr. with Leonard Crow Dog, at the apology ceremony, December 5, 2016. (YouTube)

Crow Dog raised his hand in absolution. Clark removed his cavalry hat and squirmed forward, head bent, until Crow Dog could lay his hand on his head. Ululations from the crowd, the sound of sobbing, and the men nodded at each other. A Native man sang a few bars of a song in a Native language, and Crow Dog took the mic.

“Let me say a few words of accepting forgiveness: World peace. World peace. We will take a step. We are Lakota sovereign nation. We were the nation, and we’re still a nation. We have a language to speak. We have preserved the caretaker position. We do not own the land. The land owns us.”

People hugged and cried, to more song and drums.

When a blizzard descended the morning of Monday, December 5, some saw that too as providence celebrating the victory and punishing the police, who they believed could not take winter as well as Native Americans could.

Several weeks later Clark told me how vets trying to escape the blizzard were packed “eight or nine people to a room, people sleeping in the hallways and in the stairwells” at the casino, even as he was “just walking around in circles, going room-to-room, and person-to-person, getting information as to what’s going on, and how to affect it, and what elders wanted me to do.”

He said they never rehearsed the apology ceremony. “I was standing to attention there the whole time, and I hadn’t slept or eaten—dude, I’m gonna fall over, please, please, don’t let one more person speak—and then words just popped out of my mouth.”

“[A]s the size of this blizzard started becoming apparent, the evacuation of camp became way more urgent, and, every available SUV was put into getting everybody out of camp who could. […] I spent the rest of the night walking around in the hotel, chasing down…rumors all night. I did that in coordination with the headsmen that were up there, as well as [other officials] from the tribe. The rumor [then] was that pro-DAPLs, security people, or the infiltrators that they paid, set up booby-traps by the bridge to make it look like there were explosions, in hopes of drawing some out from the camp in that direction and getting them involved, and getting them injured, and then getting to say that it was a riot.

“At the same time, because the easement had come through there was nothing more we could get, and nothing more that the Elders wanted us to do. If we did try to do anything, it would be us against them.”

Clark told me that Michael Wood, VSFSR co-founder, “arrived late Sunday night, and he had…all the access to the money. But what can we get delivered to us in the middle of a blizzard?” Clark said they needed to “come up with a system for the receipts because [Wood] promised everybody that he’d pay them…for travel expenses on the spot,” but he had to get back to his kids and figured Wood, “the other half of the thing,” would be able to handle it. A few days later, he said, he sent Wood a text to be careful with the money, and Wood replied that he did not get a vote in it.

“And I was kind of kicked out of the organization,” Clark said. “I never had control or knowledge or anything of how the money worked. They were just using my Facebook page to tie it to the GoFundMe.”

Thousands were left stranded in gyms, the casino, and community shelters. Many ran off into drifts and had to recover their vehicles later. No one I spoke to was reimbursed, as VSFSR had promised, and the storm still beat down.

An Oceti headsman told VICE, “The vets thing was a shit show.” He was Lakota but would not give his name because “it would create rifts within the camp.”

“All that work and money, and there was nothing to show for anything for the vets or for camp,” he said. “It’s in complete chaos right now because of this vet event.”

On December 8, Clark offered his other apology, on Facebook, “for the massive logistical problems that occurred at Standing Rock in the last few days. We did not have the communications, command structure, or organizational capacity to deal with it.”

He said the “action was successful thanks to the sacrifice and hard work of those who were on the ground before us and endured the risk, pain and suffering when the eyes of the world were not on Standing Rock—the water protectors, the youth, and the elders who have instructed us from the day we arrived that faith, prayer and peace are the way forward.”

He also said the veterans were “what tipped the scales and made this happen—know it.”

Both were correct.

• • •

Oceti Sakowin depopulated quickly. Almost everything—tipis, vehicles, tools, tents filled with donated clothing and food, propane tanks, dumpsters, toilets, personal (even sacred) belongings—was left and lay under feet of snow and a rime of ice.

Participants seemed to have left with a complicated mix of feelings: accomplishment, fatigue, disappointment, and embarrassment at how ineptly things had gone, especially given bragging by VSFSR leadership that veterans could out-plan the police and adapt to any situation.

There was also a creeping gloom that when Trump took office, things would reverse. The realization was slow. Trump was long known to have been invested in Energy Transfer Partners and other pertinent oil interests, and no proof was offered that he had divested.

If the easement decision was reversed, allies would face a choice. If the fight was proper the first time, why not a second? Stakes would be higher the second time, as Trump showed authoritarian tendencies, and more travel meant money and time.

I went back to Oceti in January to document any push for return. There was nothing much to do, and those who remained had consolidated resources and moved toward the center of camp, leaving tipis abandoned and tents collapsed under snow.

On January 5 there was an informal Standing Rock Tribal Council meeting in Ft. Yates to discuss the future of the camps. There was not even standing room in chambers, and a crowd in the hallway bubbled with comments against closed doors.

Standoffs continued on the Backwater Bridge in January 2017. (Photo by John Griswold)

Many of the publicly recognizable figures were there—Dave Archambault II; Dennis Banks; his sidekick, Robby Romero, a musician and filmmaker connected to Hollywood; and LaDonna Tamakawastewin Allard, Phyllis Young, Paula Antoine, and Chase Iron Eyes, representing the camps.

The main order of business, Archambault said, was to make clear that Oceti was built on a floodplain, and everything on it would be swept into the Missouri River when the historic snows melted. This would become a hazard downstream and a public-relations nightmare. The Standing Rock Tribe would be fined, when they were already in one of the poorest counties in the United States and financially strained by opening facilities and giving money and resources to fight DAPL.

There were hisses of protest and suspicion. Archambault stressed this was not about kicking people out.

Participants seemed to have left with a complicated mix of feelings: accomplishment, fatigue, disappointment, and embarrassment at how ineptly things had gone, especially given bragging by VSFSR leadership that veterans could out-plan the police and adapt to any situation.

“I know there’s been a lot of waáiyapi, what we call waáiyapi is rumors, that this council is corrupt, that this council is taking money, that I have a house in Florida, that I have a house in Bismarck. All of these things are not true. From the beginning the tribal council has never solicited money, never has solicited resources,” Archambault said.

Even though the movement had created something beautiful, he said—people “will talk it about it for centuries,” and it was a “huge win for Indian Country”—it had come at a cost for their membership, and they had to do their jobs and speak for and protect the members of Cannon Ball and other communities on the reservation.

Archambault addressed Chase Iron Eyes, a Native American lawyer and former US House candidate integral to the movement, by saying that sometimes “sovereignty,” which meant “do it yourself,” was confused with treaty rights.

“If we’re gonna say we’re sovereign,” Archambault said, “then we shouldn’t accept anything from the federal government, including food stamps.” Or donations from outside, he suggested: there had been 80,000 donated packages in Bismarck, which the tribe had to bring down to the reservation and stage in tribal warehouses. Then they’d been accused by some in the movement of hoarding, and people came to shout at Archambault: Where’s my package?

Archambault said that they were going to bring treaty rights forward in a lawsuit, because, for the first time, the federal government had mentioned those obligations “in statements released by the Departments of Justice, Interior, and the Army.” But the treaty was with the Great Sioux Nation, not with individual tribes like Standing Rock or Rosebud, and he wished all of them would come together to litigate, since individually they would lose.

As for anything more radical than lawsuits, he said, “This tribe, this body, never wanted to fight.” He was asked in California: When political-legal approaches lose, will you put blood on the line to stop this pipeline? He said he answered: “No, I can’t do that.” He said he had seen the T-shirts with black snakes that had their heads cut off (LaDonna Tamakawastewin Allard, who was wearing one, and who claimed the vets were willing to “deploy” again, looked down), but he wanted everyone to know that this was just one pipeline, and there were many coming.

“If we want to stop these pipelines, the oil industry is the fight. Not the pipeline. Not the one snake, not this snake.” He said he was proud of what had been accomplished, that it was a huge win for all Indigenous people everywhere. But, “If we want to lay our blood down in front of this one snake, it’s going to take that win away.”

For hours participants spoke about the path forward, with much contention.

Phyllis Young served as a council member from 2012 to 2015. She was one of the most prominent matriarchs in the movement, a longtime member of AIM, and had served on the board of the National Museum of the American Indian. She was photogenic in graduated shades and well-spoken. She thanked everyone and said she was overwhelmed by the response. “There is no footprint for this,” she said. She believed it was a response from the universe to her people.

“We are universal,” she said. “And we are a pluralistic society. So we have balance. And we are seeking that balance as we endeavor against all odds. […] So we have prayed for the Thunder Beings to come, and they have entered our prayer. […] We have had the blessings of five fallings-of-snow. And we follow the natural order…and so we are bound by that natural law to move our camp.”

One could feel the room understand: that was that.

Young said they had fought Keystone, Keystone XL, and DAPL simultaneously.

“Our prayers were answered. That [DAPL] permit has been denied. And now we have to go forward with an aggressive agenda. For this tribe, we are proposing a treaty conference, acknowledging the United Nations’ study on treaties and accepting the international principles of the Vienna Convention.”

She said they were hiring a young lawyer to coordinate the twenty-eight Native nations on the river, and to propose that the Oceti Sakowin (the tribes popularly called the Sioux) own the entire Missouri River and administer it. She said they already owned the dams, and that the feds owed them $5 billion for hydropower generated on the river.

“It’s been my rallying campaign,” she said. “If the United States is still a republic, and if it’s still governed by the Constitution, and treaties are the law of the land, then we will prevail.”

A delegation of women was leaving for DC to go to the National Museum of the American Indian to discuss a Native veterans’ memorial on the mall; to the Million Woman March; to a proposed environmental panel with Ivanka Trump (“We’re going to influence the hell out of her,” Young told me later); to Sundance. There had been a hip-hop concert that raised $1.7 million, which was to be used for this agenda.

Dennis Banks rose and said he hated speaking after Phyllis. Everyone laughed. The famous co-founder of AIM and Wounded Knee veteran was an old man with a thin voice, and he had come to Standing Rock because he and Robby Romero—a Native rocker from the ‘90s, activist, and businessman some Native Americans called “a show pony”—were trying to put together a concert for Standing Rock in a major city.

Banks was proud that as he traveled widely all he heard about was Standing Rock. “The big news in Tokyo was Standing Rock—and then Trump,” he said. But he did not understand when he was told someone was streaming what he was saying on social media.

“Who’s security [in the room]?” he demanded.

“We’re all security,” a young woman next to me said righteously.

Archambault turned the meeting back to the second of two main concerns: that authorities might come into the main camp to shut it down, as they did with a previous camp closer to the drill pad. He did not want that fight, that flashpoint, that violence, and never had, he said.

“I was told from the beginning, people coming up, saying, ‘I’m ready to die,’” he said. “And I said, ‘I don’t want you to die! You should be finding a way to live!’

Finally, Akicita Hokšíla/Soldier Boy/George Manape LaMere got up and spoke in his role as a headsman. He said that camp must be cleared before the flood; it was never meant to last this long anyway. He chided everyone that they were not ready for traditional law and spiritual law. The whole purpose of the camp had been to assert the treaty they were trying to claim in court.

Archambault turned the meeting back to the second of two main concerns: that authorities might come into the main camp to shut it down, as they did with a previous camp closer to the drill pad. He did not want that fight, that flashpoint, that violence, and never had, he said.

“But things are getting serious now,” he said. “Somebody’s gonna end up dead. Then what? FBI? Right? Because of our own incompetence. And ignorance, as much as we like to say we’re down. We’ll see, when the FBI comes in and starts asking questions. We’ll see how down you are.” Moving the camp to higher ground was a “no-brainer.”

“Put your pride aside. You want to die? That’s ridiculous.

“We have to find out where that next prayer is…. So we’re moving! We’re not gonna talk it about it no more! We’re just gonna do it. If you stay, you stay. You’re gonna pay the consequences yourself. The spirits said that: The stubborn will learn the hard way. We had ceremonies about this already.”

• • •

Before I left I drove some of us drove down through South Dakota, almost to Nebraska, to the Pine Ridge Reservation, and interviewed Don Cuny, head of security at the Oceti Sakowin camp. Cuny Dog, as he likes to be called, was the Vice President of AIM Grassroots, had been a friend of John Trudell, and had been at both Wounded Knee and Alcatraz.

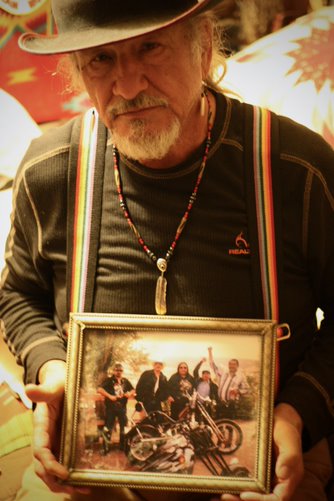

Don Cuny with a photo of his Wounded Knee comrades, January 2017. (Photo by John Griswold)

“They said that we won [against DAPL],” he said. “Hell, we didn’t win yet; it ain’t never over. As long as you’re Indigenous, and you believe in fighting for Mother Earth…I don’t care what nationality you come from…. You might as well just say you’re a warrior for the rest of your life.

He said White people especially were happy, because they came, “they didn’t stick around, now they’re gone.” But he also criticized Native people that “did not even have respect for the elders…refused to listen, because they took everything into their own hands. […] That’s probably why a lot of things went wrong, because they didn’t listen. […]

“What they wanted to do, they didn’t get to do. They didn’t get to have a shootout,” he said. “I’m glad they didn’t, because it would have got a lot of innocent people killed for trying to prove that they’re America’s next hero, or they’re Standing Rock’s heroes.”

But when I asked Cuny: If Trump reversed the Corps’ decision on January 20, would he want 5,000 outsiders showing up again for support? He laughed.

“Oh hell yeah,” he said, “armed and dangerous.”

• • •

By Inauguration Day, VSFSR had been over nearly two months, and two days later Trump reversed DAPL’s easement again with an executive memo. Native leaders began to make pleas on the Internet for veterans to return, but few went. Attention shifted to the 2017 Women’s March, the biggest single-day protest in US history, which some seemed to think would drive Trump from office. Those in the camps were given until February 22 to evacuate.

Most left early, though a dozen were arrested on the road outside Oceti that day as a show of force. A couple of resisters torched the guard shack and other camp structures on February 23, when 200 police and National Guardsmen walked through, heavily armed, armored, and accompanied by Humvees, and mopped up.

Wes Clark Jr. stopped posting about Standing Rock quickly but continued to tweet about the climate and Democratic politics. In July 2017, his profile photo showed him dressed as a Jedi, glowing in the green light of a lightsaber.

Standing Rock disappeared from mainstream media in the daily deluge of political scandals and outre behavior. But Native Americans had predicted that sparks from Oceti Sakowin’s sacred fire would be carried around the earth, and they could be seen in other Indigenous camps and movements that resisted the Bayou Bridge Pipeline in Louisiana, the TransCanada Keystone XL pipeline, and the Thirty Meter Telescope on Mt. Mauna Kea. Native alums were visible at documentary film premieres, Bernie Sanders’ office, the UN, and in “teachings” on livestreams. Standing Rock underlay the tensions of “the smirk heard ‘round the world,” and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez said it was her political awakening.

Wes Clark Jr. stopped posting about Standing Rock quickly but continued to tweet about the climate and Democratic politics. In July 2017, his profile photo showed him dressed as a Jedi, glowing in the green light of a lightsaber. His tweets said things such as, “I’ve actually smoked a joint with Christ,” “Who wants Knowledge? Ask for I know the secret of the Universe,” and “God prepared me for this my whole life. I just didn’t know it.”

He taunted “that Whore @realDonaldTrump” and said, “We live in a country responsible for killing hundreds of thousands of women and children a year and I’m the one that’s crazy?”

On Facebook, he wrote that “some of [VSFSR’s] planning staff were paid military contractors working for the other side. They have the names, emails, addresses, phone numbers, and personal information for each and every one of us that went out there or contributed money to the cause of protecting both our environment and our Constitution. Please be cognizant of the fact that all of us are on a list and that if there is civil disorder in this country, we will be the first people rounded up.”

Since then, most charged with crimes for #NoDAPL activities have been released. Several notable figures have died, including Dennis Banks, Leonard Crow Dog, Myron Dewey, and LaDonna Tamakawastewin Allard, who died of aggressive brain cancer, which she told me she blamed on the corporate state.

DAPL, built originally to deliver 570,000 barrels per day, has sent oil through the pipeline commercially since June 2017. In 2020 a US District judge ordered the Army Corps of Engineers to do a new environmental impact statement on the pipeline, expected in March of this year. Energy Transfer Partners increased capacity to 750,000 barrels in 2021, the same year the Standing Rock Sioux and others lost their lawsuit against the pipeline. Last week, an Illinois court vacated approval from the Illinois Commerce Commission to allow DAPL to push 1.1 million barrels per day.

US Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland, a member of the Pueblo of Laguna, became the first Native American cabinet secretary in March 2021. At the end of February of this year she announced the Department would use $1.7 billion “to fulfill settlements of Indian water rights claims.”

“Water is a sacred resource,” she said, “and water rights are crucial to ensuring the health, safety, and empowerment of Tribal communities. With this crucial funding from President Biden’s Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, the Interior Department will be able to uphold our trust responsibilities and ensure that Tribal communities receive the water resources they have long been promised.”

• • •

“Not Afraid to Look,” by Lakota artist Charles Rencountre, overlooks the site of the DAPL struggle. The statue is modeled after an effigy figure on a nineteenth-century Lakota pipe called “Not Afraid to Look the Whiteman in the Face.” January 2017. (Photo by John Griswold)

VSFSR was a mess of disorganization, larping, good intentions, and potential violence. It could be seen as both precursor and antipode to January 6.

The Native American camps themselves were different. Chase Iron Eyes told me that in addition to their value in the treaty fights, their value was experiential: “You need to be cold, you need to know what it’s like to start wet wood on fire for three straight hours, freezing your ass off.”

What is Oceti’s legacy at five years? Above all, it actually existed on the Plains.

Editor’s note: Portions of this essay appear in John Griswold’s new book, The Age of Profit, forthcoming from University of Georgia Press in the fall.