I was naïve about the elaborate lengths to which racists in the Armed Forces would go to put a vocal black man in his place.

—Jackie Robinsoni

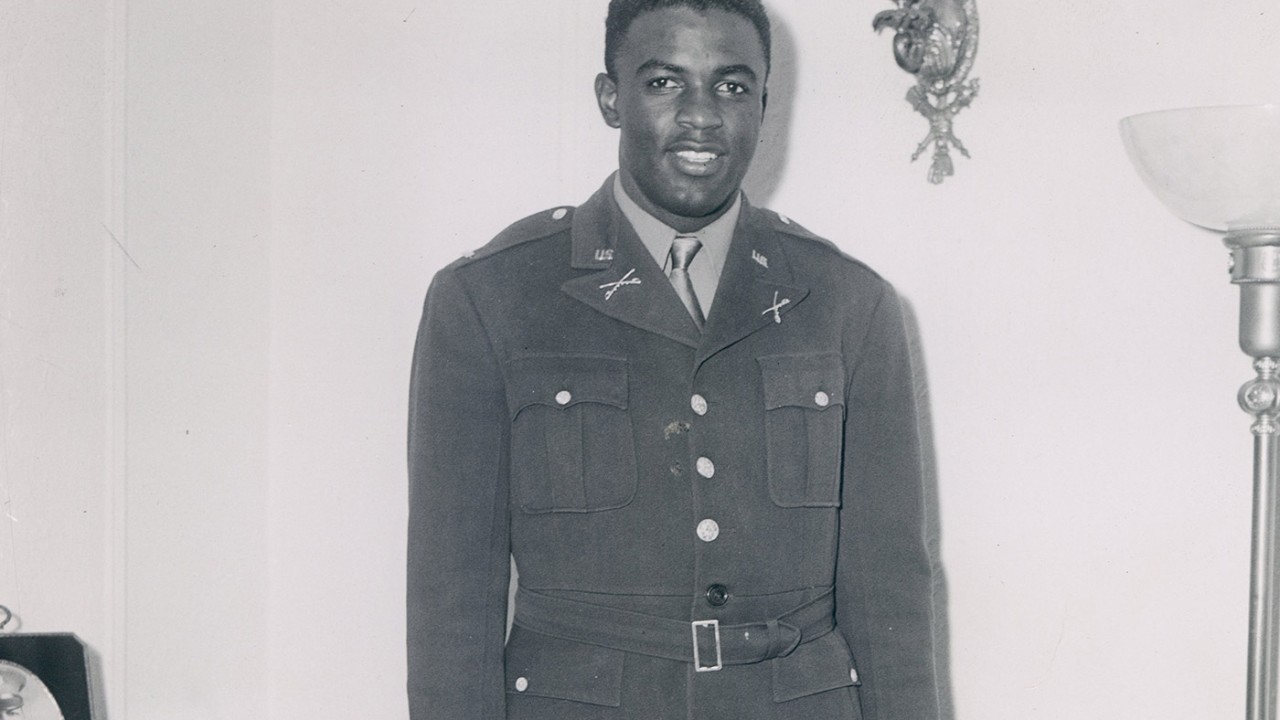

Jackie Robinson, the Hall of Fame second baseman who broke the color line in professional baseball when he signed a contract with the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1945, received his draft notice in March 1942. He was first assigned to Fort Riley, Kansas, which was strictly segregated at the time, as indeed was the entire United States military, a source for much tension between black and white soldiers during the mass conscription of World War II.

Robinson’s application for Officer Candidate School was rejected, as African-Americans generally were discouraged from pursuing officer training despite the army being racially segregated with all-black and all-white units, on the grounds that blacks lacked the intelligence, skills, and courage necessary to lead men into combat, and that if blacks were officers whites of inferior rank would have to take orders from a black. That was unacceptable, because white men, especially Southern white men, “knew the Negro best,” as the expression went and were preferred as officers for black units. Robinson complained to heavyweight boxing champion Joe Louis, who was also in the army and probably the most admired and influential black person in the country at the time, who informed Truman Gibson, a black lawyer, who was working as assistant to Civilian Aide William Hastie, selected by President Franklin Roosevelt as an election year (1940) concession to blacks (Hastie started the job in November 1940) to work in the War Department dealing with black soldiers. Louis’s ire, combined with the behind-the-scenes bargaining by Gibson and Hastie that had already persuaded the top brass to reconsider the policy, and the general unrest among black soldiers being denied the opportunity to become officers, led to the integration of officer training by the fall of 1942. Robinson was commissioned as a second lieutenant in January 1943. In April 1944 Robinson, who had been suffering from a chronically sore ankle since entering the military, was transferred to Camp Hood, Texas to the 761st Tank Battalion. Arnold Rampersad, Robinson’s authorized biographer, wrote “… Camp Hood was often a horror. The hot land crawled with rattlesnakes, tarantulas, black widow spiders, and scorpions, and the humid air buzzed with mosquitoes and other sniping insects. In addition, black soldiers and civilians had to deal with raw aspects of Jim Crow…. Black soldiers, quartered in the least desirable part of the camp, in makeshift housing, lived segregated lives at every turn, with a separate USO and a separate officers’ club; venturing off the base, they faced a hostile, narrow-minded local population backed by stringent Jim Crow state laws and customs.” It was here that Jackie Robinson was court-martialed.ii It started on July 6, 1944, when he refused to go to the back of the camp bus.

In the depositions of the whites, the white woman present at the incident are always referred to as “ladies” and the black woman who was with Robinson, Virginia Jones, wife of a black First Lieutenant, is always called “a colored girl.” The racial hierarchical distinctions are clearly delineated in the language of the depositions.

Robinson described fully the incident that led to his court-martial in his first autobiography, Wait Till Next Year (1960), written with black journalist Carl Rowan. Robinson got on a bus with a black woman who was so light-skinned that she could pass for white. Apparently annoyed that a black soldier was sitting next to what he thought was a white woman, the bus driver yelled at Robinson to move to the back of the bus, mostly because he was sitting next to a white woman, rather than strictly because of where he was sitting on the bus.

“The driver stopped the bus and walked over to where Robinson and the woman sat.

“Listen, you, I said get to the back of the bus where the colored people belong.”

“Now you listen to me, buddy; you just drive the bust and I’ll sit where I please. The Army recently issued orders that there is to be no more racial segregation on any Army post. This is an Army bus operating on an Army post.”

“You just let me tell you, buddy,” said the driver, “if you ain’t off this bus by the time we get to the last stop, I’m going to cause you a lot of trouble.”

“I don’t care what kind of trouble you plan to cause me,” snapped Robinson, “You can’t cause me any trouble that I haven’t already faced. I know what the regulations are and I don’t intend to go to the back of this bus. So get out of my face and go drive the bus because I don’t intend to be pestered by you any more.”

“The driver mumbled angrily as he stalked back to his seat.”

When the driver reached his last stop, where Robinson and his companion would have boarded a city bus, the driver left the bus and returned with three white men. One of the white women passengers on the bus began to berate Robinson and Robinson got into an altercation with one of the white men whom the driver brought back with him. At this point, two military policemen arrived. Because of the number of violent encounters between black soldiers and white MPs, sometimes even between black soldiers and black MPs, the arrival of the MPs meant things could have gotten a great deal worse. Fortunately, there had been some efforts since 1943 to improve MP training. The MPs took Robinson to see Captain Gerald M. Bear. Robinson’s companion offered to accompany him but he told her to go ahead with her trip.

Robinson was questioned by Bear and by Bear’s secretary, a civilian and a Texan who remarked that Robinson purposely wanted to start trouble on the bus by sitting where he did, an indication that local whites felt that non-Southern black soldiers were too assertive and too likely to challenge local segregation customs and laws. Robinson resented her questioning and asked Bear if he had to be subjected to an interrogation by his secretary, to which Bear responded by calling him “uppity and out to make trouble.” The secretary angrily left the room, expressing her feeling that Robinson had insulted her. Bear had Robinson submit to a sobriety test.

Two weeks later, Robinson was charged with insubordination, disturbing the peace, conduct unbecoming an officer, insulting a civilian woman, and refusing to obey a lawful order of a superior officer. Colonel Bates refused to sign the charges, expressing the opinion that Bear had conducted an incompetent investigation. Robinson was then transferred from Bear’s battalion to the 758th Tank Battalion, whose commander signed the charges. Several black officers, deeply concerned that Robinson was being railroaded, publicized the case, as a way of protecting Robinson, by notifying the NAACP and the two leading black newspapers of the day: The Pittsburgh Courier and The Chicago Defender. When this happened, Robinson was notified that several but the most serious of the charges were dropped. He was, according to his autobiography, finally court-martialed—The United States v. 2nd Lieutenant Jack R. Robinson, 0-10315861, Cavalry, Company C, 758th Tank Battalion— on August 2, 1944, or according to Army records, August 3, 1944, on two charges: that he behaved disrespectfully to a superior officer, Bear, and that he disobeyed an order from a superior officer, Bear. Colonel Bates testified on Robinson’s behalf. Bear’s testimony did not hold up well under cross-examination and Robinson was acquitted. This is Robinson’s account, generally substantiated by the actual records.iii

To be sure, Robinson did not base his account merely on his memory. He formally requested a copy of his Army records in April 1958, which he said he needed to write a book, undoubtedly Wait Till Next Year, which was published two years later. The Army replied in May, sending him, not his records, but a one-page official statement of his military service full of errors, for instance, incorrectly stating he was discharged in January 27, 1943, which was actually the date, January 28, 1943, that he commissioned as a Second Lieutenant, which meant that according to the Army he was discharged and then given a commission. He was, in fact, court-martialed in 1944, as mentioned above. In June 1958 Robinson desperately repeated his request and the Army responded by sending a copy of his General Court-Martial Orders.

There are three types of courts-martial: a summary court-martial is for minor offenses which usually, if the defendant is found guilty, results in a reduction of pay and possible short-term confinement of 30 to 60 days. A special court-martial is for more serious offenses where the enlisted defendant can request a jury composed of one-third enlisted men or be solely tried by the judge. The maximum penalties are loss of two-thirds of pay for one year and possible confinement for up to one year. Finally, there is the general court-martial for the most serious cases. Punishment can include death (for some capital charges), multi-year confinement, and dishonorable or bad conduct discharge. Robinson had a general court-martial, and had he been convicted almost certainly would have been dishonorably discharged from the service which would have made his later, Major League Baseball career impossible.

In his later autobiography, I Never Had It Made (1972), Robinson tells substantially the same story, only shortened. This time, in recounting his interrogation at the hands of Bear and his display of irritation to Bear’s secretary, Robinson writes that Bear “growl[ed] that I was apparently an uppity nigger.”iv This is not a direct quote of Bear’s and in the earlier autobiography, where Bear is directly quoted, Robinson has Bear call him uppity, but not a nigger. This is not because the first autobiography is reluctant about using the word “nigger” in relation to this incident. According to Wait Till Next Year, the first time anyone uses the word nigger is when the passengers have disembarked at the last stop and a woman whom Robinson recognizes as the saleswoman at the post exchange says, “I heard the driver tell you several times to get back there where niggers belong.” She denies this in her deposition. One of the three men who was called upon the scene then said, according to Wait Till Next Year, “Is this the nigger who’s causing all the trouble?” Who called Robinson a nigger and when is actually important in understanding what happened or how Robinson understood what happened, as I will discuss momentarily. The account of the court-martial is the same in both autobiographies. Ultimately, Robinson is given an honorable discharge, or more precisely, a medical discharge in November 1944, for having the bad ankle that had been a source of persistent discomfort to him.

Reading the official depositions of all the witnesses and actors in the bus incident that led to Robinson’s court-martial, a few things become clear. First, it is a certainty that the bus driver, Milton N. Renegar, was not armed. Robinson almost certainly would have been shot, if the bus driver had been, as he likely would have used his weapon and Robinson would likely not have been able to disarm him. Nowhere in the record is it mentioned that the bus driver was armed. This is contrary to Truman Gibson’s account of this incident—by 1944 he had become Civilian Aide after the resignation of William Hastie—in which he not only states that “the bus driver drew a revolver,” but that Robinson “wrestled the pistol away and massaged the driver’s mouth with it, depriving him of many teeth.”v There is nothing in the record to support Gibson.

It is true that the army issued an order to integrate its buses in 1944, but as Kimberley L. Phillips writes, “commanders in the South maintained segregation.”vi There was an ongoing struggle between black soldiers in their fight against the humiliation and intense physical discomfort of Jim Crow travel. On March 14, 1944, Private Edward Green was murdered by a bus driver in Alexandria, Louisiana. Standing up to Jim Crow on base buses was dangerous not only to a black soldier’s career but to his life. The Robinson bus incident happened on July 6. In the film The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson, it is stated that a black soldier was killed by a bus driver just two weeks earlier. Robinson likely would have been far more circumspect had the driver been armed. Knowing that so many black soldiers so disliked Jim Crowism on the base and resisted it mightily, it is surprising that the driver wasn’t armed. I am certain Robinson would have been shot if the driver had been armed because the driver, as well as several of the other witnesses, made it plain that they thought Robinson had been disrespectful to white women. He talked back to and allegedly cursed a white woman passenger on the bus, Elizabeth Poitevint, a civilian employee at PX #10, who objected to his behavior and said she was going to report him to the MP’s. (Incidentally, he was to talk back to Captain Bear’s secretary while he was being interrogated which caused her to leave the room.) Also, he was asked to move to the back of the bus, in part, at least, because several white women with their children were boarding the bus and the driver particularly didn’t want to have them “mix” with him and his black female companion. The bus driver testified in his deposition: “On this particular run I have quite a few of the white ladies who work in the PX’s and ride the bus at that hour almost every night. I did not say anything to the colored Lt when he first sat down, until I got around to bus stop #18, and then I asked him, I said, ‘Lt, if you don’t mind, I have several ladies to pick up and will have a load of them before I get back to the Central bus station, and would like for you to move back to the rear of the bus, if you don’t mind.’” Whether the driver asked Robinson to move in such a polite manner is open to considerable doubt, but it is a fact that the driver did not ask Robinson to move immediately upon Robinson and his companion boarding the bus and sitting where they did, which was about in the middle of the bus. The movie correctly dramatizes it in just this way: the driver drove several stops before telling Robinson to move. The white PX clerk underscores both the points about white women getting on the bus and this causing special tension in her deposition that at a certain stop, “some white women, most of them with their babies, got on the bus.” In this regard, there is a thin line between Robinson’s conduct as an officer and a gentleman and willingly going to the back of the bus as a polite gesture to the women boarding the bus and his going to the back of the bus as a sign of submission to a racist system. Would a white officer have shown such regard if some black women and their children were boarding the bus? For Robinson, the situation seemed even simpler: would a white officer have been asked to move? Whatever the case, the sexual aspect of this is especially explosive. In the depositions of the whites, the white woman present at the incident are always referred to as “ladies” and the black woman who was with Robinson, Virginia Jones, wife of a black First Lieutenant, is always called “ a colored girl.” The racial hierarchical distinctions are clearly delineated in the language of the depositions.

In the film The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson, (1990), the n-word is thrown around gratuitously in the bus incident scene. But for it to have so bothered Robinson and for him to threaten someone he felt may have used the n-word would more likely indicate that it was not used excessively but pointedly.

Second, Robinson was clearly incensed by someone calling him “a nigger,” or something he heard as “nigger.” Robinson, according to Captain Peelor Wigginton’s deposition, at one point said to Wigginton, one of the white officers who questioned him after he was taken into custody, “Captain, any private, you, or any general calls me a nigger and I’ll break you in two.” Robinson was referring to Private Mucklerath who, Robinson thought, called him a nigger. Mucklerath, in his deposition, admits that Robinson threatened him in this way but denies calling him “a damn (sic) nigger.” All deposed parties, including Robinson, agreed that Robinson made this threat. All the whites who were deposed denied calling Robinson a nigger or even hearing anyone calling him such a name. According to Robinson’s deposition, the bus driver also called him a nigger. In the film The Court-Martial of Jackie Robinson, (1990), the n-word is thrown around gratuitously in the bus incident scene. But for it to have so bothered Robinson and for him to threaten someone he felt may have used the n-word would more likely indicate that it was not used excessively but pointedly. The scene in the film would actually have had more power had the word been used sparingly, as it would have had a more jarring impact on the audience. Robinson told someone “to stop fucking with me.” In his disposition, he said it was the bus driver but Ms. Poitevint thought Robinson said this to her, which he might have if she called him a nigger as he writes that she does in his first autobiography. Several of the white deponents accuse Robinson of using vile and obscene language in the presence of the white women. Robinson’s companion, Virginia Jones, said in her statement that she “did not hear him say anything vile nor vulgar at any time, not he did not raise his voice.” But she never mentions if anyone called him or her, for that matter, the n-word. Robinson clearly saw the incident as an assault on his black manhood; the masculine sense of contest and authority that undergirds the entire incident is captured in the dispute over language, over verbal jousting as a form of both power and resistance. Robinson hears the denigrating insult “nigger,” and the whites hear Robinson use words like “fucking,” “son of a bitch,” and other such phrases as he stands up for himself against both white men and white women in the incident. They are racist in their language and he is no officer or gentleman in his.

The other aspect of language here is that Robinson, like many other black soldiers who resisted Jim Crow regulations, always insisted that they knew “the regulations,” that the army had discontinued its segregated bus policy earlier in 1944 and so Robinson “had no intention of being intimidated into moving to the back of the bus”vii In other words, Robinson felt his actions were backed by the law, by an official text that protected him in a highly structured and legalistic institution, the military, that was unquestionably obedient to “the regulations” that governed it, which, I suppose, is the origin of the phrase in the military, “by the book.” In great measure, the entire episode is about the politics of language and race in the military.

Third, after being taken into custody and vigorously and counterproductively arguing his side of the story, Robinson became convinced that the white officers were mounting a conspiracy against him and that he would not get justice. The fact that Robinson was acquitted did not have as much to do with the strength or weakness of the prosecution’s case as it did with the fact that Robinson was somebody, not a nobody. He had been a star college athlete and his brother, Mack, had been on the 1936 Olympic track and field team. Robinson knew Joe Louis, who used his influence to help him. Robinson wrote letters to powerful people and had letters written on his behalf, some of which can be found in these archives. In a July 1944 telephone conversation between Colonel Kimball of Camp Hood and Colonel Buie of 23rd Corp, it is clear the Army’s top brass was aware of the hot potato they were trying to handle. Kimball said “the case is full of dynamite” and “requires very delicate handling.” Kimball wanted an outside inspector for the case, afraid that all the men at Camp Hood would be “prejudiced.” Buie said he had no inspector immediately available but would send one as soon as possible. So, Robinson was acquitted, probably, because it was the most expedient way for the Army to get rid of him without making him a martyr or a cause celebre among the black leadership and the white liberal and radical left.