Camp: Something so outrageously artificial, affected, inappropriate, or out-of-date as to be considered amusing; a style of mode of personal or creative expression that is absurdly exaggerated and often fuses elements of high and popular culture. —Merriam-Webster

Back in college, I fell half in love with a guy in my philosophy class, a seminarian (the allure of the forbidden) with a strong Scottish jaw and a fondness for tweed jackets. Luckily, he made no secret of being gay (thus really forbidden), so we eased into a real friendship, talked about our dreams, confided weird theories about the world. I thought I knew him inside-out.

Then one day, flipping through an album, I saw photos of him with other gay friends, camping it up. Stephen of the tweed jackets wore a satiny dress and a lipsticked pout, one hand up in a classic here-I-am pose. Everybody at the party was in drag, and it stung, because their poses mocked the traditional feminine world I was poised to enter. Yet there was no meanness; the mood seemed generous and silly, with a sort of manic hilarity. The parody was self-parody, I realized; they were seizing a freedom they felt nowhere else, thumbing their noses at the whole bloody world.

That moment became my private definition of camp. It helped me appreciate drag and cross-dressing and gender-bending; it hinted at just how much is lost when people cannot live fully as themselves. But as the years went on, and some of my favorite childhood television shows (Mod Squad! The Avengers!) were pronounced camp—along with the hetero-sexy noir of The Maltese Falcon and goofy Bubba Ho-Tep and Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Theresa—I grew more and more confused. When I tried reading up, I noticed that at some point, everyone quoted, either with admiration or fury, the same source: Susan Sontag’s 1964 essay, “Notes on ‘Camp.’”

Watching Sontag thread her ideas through a calculated jumble of examples, I realize with a tiny thrill of schadenfreude that she is spitballing. She is doing it brilliantly, but she is spitballing, using the list format instead of her usual tight weave because she is trying to pin down a sensibility as elusive as a butterfly. Camp is anti-serious, she writes, “a comic vision of the world”—yet, she adds, it must be done thoroughly and with passion, or it will only be pseudo-camp. Its purest form is naïve, unwitting, yet it “sees everything in quotation marks.” Its originators were a self-selected aristocracy of taste, yet camp is so coarse that it could easily be called tasteless. It is one-dimensional, preoccupied with surfaces, yet it is “a kind of love,” “a tender feeling.” It is “corny flamboyant femaleness” and “exaggerated he-man-ness,” yet “the androgyne is one of the great images of camp sensibility.”

Watching Sontag thread her ideas through a calculated jumble of examples, I realize with a tiny thrill of schadenfreude that she is spitballing. She is doing it brilliantly, but she is spitballing, using the list format instead of her usual tight weave because she is trying to pin down a sensibility as elusive as a butterfly.

Her examples are equally confounding. Tiffany lamps, really? Flash Gordon comics and Swan Lake, sure, but why Schoedsack’s King Kong but not Ishirō Honda’s King Kong vs. Godzilla? Why Mozart and not Beethoven, El Greco and not Rembrandt? This could be a board game. And is not Shakespeare, with all his witty exaggerations and inversions, sometimes a wee bit campy?

On second reading, many of the apparent contradictions resolve. Camp is serious about frivolity, frivolous about what others have taken seriously. It lets low culture crash the cocktail party, conjoins base desires with art, redeems awfulness by placing it in ironic context. As clues, I scribble down quotes like this one: “With his 1949 avant-garde short film, ‘Puce Moment,’ Kenneth Anger is vomiting glamour into our face, objectifying objects, sexualizing what cannot, in a vacuum, be sexualized: silk, velvet, cotton, glitter—and we cannot get enough of it.” In love with excess, camp sails right over the top, using artifice and theatricality and absurdity.

From this blur of traits, a fresh question emerges: What would Sontag label as camp today? Some of the more stylized new horror films might fit. Lady Gaga in her meat dress. Dan-O-Rama. Rainbow Randy. Psy, the South Korean rapper who gave us “Gangnam Style”—or is he simply high-energy? The Kardashians, or are they simply vulgar? Camp, as we have established, is not simple. I would plump for Ann Taintor putting purple mountains in the background as a woman with a fur stole swung around her neck raises a white-gloved hand and, smiling gaily, tells her equally well-dressed friend, “You be Thelma. I’ll be Louise.” Or Amy Sedaris in Simple Times: Crafts for Poor People, teaching us how to roast wienies on old rakes and use leftover coffee grounds to cushion a hospice for a dying mouse. Does all parody qualify? RuPaul’s Drag Race is a mainstream Emmy Award-winner now, and Dame Edna is household. Looking for someone edgier, the likeliest example I find is Leigh Bowery, “an Australian who affected an upper-crust British accent while dressed like a cross-dressing Mexican wrestler on LSD.” Alas, he has been dead for a quarter-century.

Camp’s initial burst of energy came from a gay subculture that is now open to the public, with no need to whisper, pass notes, and set secret passwords. Camp’s exaggerations of masculinity and femininity revealed the rigidity of gender norms, but those norms are fluid now, categories fast vanishing into the nonbinary “they.”

That is when it hits me. Maybe camp is dying, too.

The more I think about this, the more sense it makes. Camp’s initial burst of energy came from a gay subculture that is now open to the public, with no need to whisper, pass notes, and set secret passwords. Camp’s exaggerations of masculinity and femininity revealed the rigidity of gender norms, but those norms are fluid now, categories fast vanishing into the nonbinary “they.” Camp loves only artifice, but we have begun to crave nature—especially now that we have nearly destroyed it. Camp is brilliant at introducing irony where it once did not exist, but now irony exists everywhere; its distance and layering are our habitual mode of perception, absent only in cults and Waldorf preschools. What role is left for camp to play?

• • •

Antinous, the beautiful young lover of Emperor Hadrian, died young, and in a burst of grief, Hadrian deified him, building temples and commissioning statues in his image. Just as women are taught to turn their hips for a standing group photo so they look slimmer, Antinous was sculpted with his shoulders turned, his weight resting on his back foot, one hip jutting out, and that arm bent at the elbow, the hand turned back—a pose that highlighted the masculine ideal. By the seventeenth century, he was bathed in homoerotic admiration. At Versailles, Louis XIV’s similarly exaggerated contrapposto pose read as aristocratic—and distinctly effeminate. The playwright Moliere instructed a male character to “camp about,” posturing in this stylized and dramatic way.

By 1870, the ideal was seen as deviance. “Homosexual” was no longer a description of behavior but a label slapped onto a person, and in London at least, “campish undertakings” were presented as incriminating evidence of homosexuality. Clad—no, costumed—in velvet, Oscar Wilde defiantly resurrected the camp pose, determined to live as himself.

As “camp” became disapproving late-Victorian slang for “actions and gestures of exaggerated emphasis,” gay culture went deep underground. Camp became a charged mixture of secret codes and “look at me” flamboyance. After spending so much of life trying not to be seen, a hunger was growing, a need to be more and more outrageous, an extravagantly frothy bubbling up of what had been denied.

“Camp is a lie that tells the truth,” Jean Cocteau announced in 1922.

“Only two things [are] essential to camp,” writes Philip Core in 1984: “a secret within the personality which one ironically wishes to conceal and to exploit; and a peculiar way of seeing things.”

As more and more people grasped its deliberate skew, camp became a subversive mix of playful exaggeration, stylized artifice, weaponized kitsch, and over-the-top fun.

Then Sontag picked up her pen.

It was the Sixties, and the world was changing fast. The gay rights movement was beginning. Sexual “liberation” was redefining both masculinity and femininity. Pop culture was issuing its own challenge to the status quo, with just as much bright fun and artifice but far less edge.

Sontag acknowledged camp’s gay “vanguard,” but she broadened the definition to include a lot of that pop culture—not just the new color TV’s Batman and other costumed superheroes but silliness like Gilligan’s Island and, later, Dallas and Dynasty. Some critics blame her for slipping a taste for vulgarity into the definition of camp; they say she almost singlehandedly shifted the criteria to include “anything so bad it’s good.” To her, camp was apolitical, an alchemy of perception and an aesthetic retrieval that showed the absurdities of the past.

“Sontag killed off the binding referent of Camp—the Homosexual—and the discourse began to unravel,” wrote Moe Meyers. He accused her of plundering the dead queer’s estate, using the art form but detaching it from the queer culture that produced it.

“Sontag had a contentious relationship to the queer culture from which camp emerged,” Stephen Houldsworth, a civil rights activist steeped in psychology and philosophy, reminds me. “She attempts to define camp, while at the same time claiming it can be separated from its roots in the pain of queer existence.”

“Sontag killed off the binding referent of Camp—the Homosexual—and the discourse began to unravel,” wrote Moe Meyers. He accused her of plundering the dead queer’s estate, using the art form but detaching it from the queer culture that produced it.

Right up front, Sontag admitted that camp induced a certain personal revulsion. She traced its history to “an improvised self-elected class, mainly homosexuals, who constitute themselves as aristocrats of taste.” Then she pried camp out of their hands and gave it to the rest of us. And once camp was more about cultural objects than queer performance, you could argue that it became a bloodless curiosity. No longer animated by anger or passion, it often lost the plot, spinning off into all sorts of pop culture categories for its own amusement.

If camp can be just shallow fun, stripped of its original cultural subtext and bubbling with Glee and GLOW, is anything left but hype and parody?

• • •

“Failed Seriousness,” from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute exhibition “Camp: Notes on Fashion” (Image courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, BFA.com/Zach Hilty)

Last spring, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute unveiled an exhibition titled Camp: Notes on Fashion. The fearsome Anna Wintour oversaw the gala, with Lady Gaga an amused cochair. Trashily glammed up, New York’s art lovers squinted at the walls, covered with quotes from Sontag and the critics who followed in her wake. “We are experiencing a resurgence of camp, not just in fashion but in culture in general,” announced curator Andrew Bolton. “Camp tends to come to the fore through moments of social and political instability, when our society is deeply polarized. The 1960s is one such moment, as were the 1980s, so, too, are the times in which we’re living.”

The Met show paid homage to camp’s history, starting with a bronze statue based on the Vatican’s (a quiet touch of irony) Belvedere Antinous. There were portraits of Louis XIV and Oscar Wilde and tributes to the Harlem Renaissance and the black and Latin drag ball culture that was born there and gave birth to the acrobatic, attitudinal dance style called vogueing. But all this social history was merely backdrop for, say, a double-beaked, sinuous-necked flamenco headpiece for the House of Schiaparelli; Virgil Abloh’s little black dress emblazoned with the words “LITTLE BLACK DRESS”; Galliano’s extremely impractical fusions of ancient Egypt and outer space. The point was couture, and couture will always be campy, just by virtue of its artifice, glamour, and necessary exaggerations. Off the rack does not read on a runway.

Still, Bolton clearly wanted the clothing to signify more. He told The New York Times that “it felt very relevant to the cultural conversation to look at what is often dismissed as empty frivolity but can be actually a very sophisticated and powerful political tool, especially for marginalized cultures. Whether it’s pop camp, queer camp, high camp or political camp—Trump is a very camp figure—I think it’s very timely.”

A GoogleTrends search for the word “camp” sinks to the baseline for the past five years with a single exception, mid-May 2019, the time of the Met exhibition. That is not a resurgence.

A friend snorts when I read that quote aloud: “Trump’s not camp. He’s just crude.” It is the golden toilets and towers, the raising up of vulgarity, that tilt him toward camp, but it is the unintented sort, devoid of irony and closer to kitsch.

Curious whether the show sparked other celebrations of camp, I call Bolton. He is busy preparing the next exhibition, I am told, and does not want to talk about last year’s.

A GoogleTrends search for the word “camp” sinks to the baseline for the past five years with a single exception, mid-May 2019, the time of the Met exhibition.

That is not a resurgence.

• • •

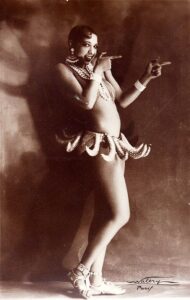

With her towering fruit headdresses and playful lyrics, Carmen Miranda gloriously camped up her tropical, biracial, lower-class Bahian identity. Many in her audience ogled or laughed, but in retrospect, it was clearly a political act. Often she would undo a bit of her costume or slip off her Ferragamo platform shoes, exposing the self-parody.

Josephine Baker in her famous banana skirt, redesigned in 1986 with a metal-wire top by African-American designer Patrick Kelly to make a queer-camp comment on the black body as consumable. (Credit: Walery)

Now, despite the preservation efforts of Brazilian museums, the plastic sequins are falling off all those papier-mache bananas, grapes, and pears, and the fabric in her costumes, fibers weakened by multiple alterations and the sweat of performance, is slowly dissolving. And where is the sequined, phallic banana skirt Josephine Baker wore to taunt those who equated Africa with sex and savagery? Did that, too, fall apart? No matter: In 1986, African-American designer Patrick Kelly redesigned the skirt with a metal wire top, making a queer-camp comment on the black body as consumable. And Stella McCartney’s banana T-shirts for Chloé made the Met show. And at Art Basel this December, Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan duct-taped a banana to the wall and charged $120,000 for it, using a bit of faux deception (the “work” was titled “Comedian”) to reveal a truth about the art world.

If camp has dissolved into other things, they will clearly involve bananas.

The later examples, though, lose a little of the camp twist, because they are too obviously what they intend to be. While Miranda and La Baker were appreciated on multiple levels, Kelly’s reimagined banana skirt does not pretend innocence. Neither does Cattelan’s duct-taped banana, which just tweaks the art world’s nose.

If camp has dissolved into other things, they will clearly involve bananas.

There are two main camps of camp, it seems: the self-conscious sort that pokes at solemn, prissy, hateful norms, hoping they will giggle, and naïve camp, a “failed seriousness” (Sontag’s phrase) that has no idea how absurd it is.

Is either still viable?

John Waters, crowned the king of camp for the sort of films he no longer makes, told Vanity Fair, “I don’t know anyone today who would still say that word. Even old queens talking about Rita Hayworth in an antique shop wouldn’t say camp… Camp was a secret word that gay people knew that straight people didn’t, that meant something was so bad it was great but they didn’t know it.”

Waters could not make Hairspray today, because the sort of artifice that inspired it is no longer tightly contained, significant, and politicized. “A faux mohawk look? Now Trump supporters wear that. Dyeing your hair green? Your mother does that now,” he said. “It has to be something innocent that tried to be good, that was so bad, like the movie Boom! That’s the true meaning of the word. If you’re trying, like the Met Gala where everybody gets dressed up and spends a fortune, that’s not camp.”

But a boxed set that includes Carol Burnett, Vicki Lawrence, and Mama Cass in Bob Mackie ponchos, singing, “They paved paradise and they put in a parking lot” in front of smokestacks belching pollution? Is definitely camp. “Something is so bad, it’s good—that, to me, is legitimate,” says Mike Isaacson, Broadway producer, executive producer of The Muny, recipient of multiple Tony awards, and the proud possessor of that boxed set.

John Waters, crowned the king of camp for the sort of films he no longer makes. (Credit: Shutterstock)

I can think of a few prime examples of my own, not least the Bigfoot porn flick The Geek, shot in the exotic Himalayan locale of a state park somewhere, with Bigfoot emerging from behind a dead tree and the buttons visible on his fur coat. My husband was in hysterics, but Oscar Wilde would spin in his elegant coffin.

“When Newsweek needed a cover shot of Monica Lewinsky and had no other options, so it used her employee ID photo and ran her face huge on the cover”—that was naïve camp, Isaacson continues, making sure I have grasped the concept. “Or when someone took a picture of the Dallas Cowboys cheerleaders cheering in front of a casket. There has to be an outside frame of judgment, a sense of perspective. A knowing removal from the object or performance, even as you embrace it, that perceives why it’s so bad.”

Camp in Oscar Wilde’s sense is harder to come by today, he adds gently. “It’s harder to create any removal or distance now, because we know everything. Camp only fulfills its original sense if the source retains some mystery, and mystery is deader than camp.”

That is exactly where I was heading, but now, perversely, I find I want to argue for the endurance of camp as playfully political. Isaacson shakes his head; he sides with Sontag and Waters in their insistence that pure camp is naïve, not agenda-driven. He is not sure camp was ever agenda-driven: Even drag queens, back when we were all so easily shocked, were often just having fun expressing themselves, he maintains, “with maybe a shot of theatrical misogyny. It was the nascent expression of what we have now discovered is gender fluidity. They weren’t doing the wigs and makeup thinking, ‘This is going to change the Constitution.’”

Camp in Oscar Wilde’s sense is harder to come by today, Waters adds gently. “It’s harder to create any removal or distance now, because we know everything. Camp only fulfills its original sense if the source retains some mystery, and mystery is deader than camp.”

Fair enough. But when you are expressing an identity that is not permissible with most of the world, that still feels pretty political to me. “Camp is a perspective on life, an acknowledgment that nothing is really important, so, of course, everything is,” Houldsworth told me. By taking that stance, it can play with secrets and taboos, draining their power. It is self-conscious, even arguably activist. And it is very different from relishing naïve awfulness or absurdity.

I wave a quote from film studies scholar Richard Dyer, describing the camp sensibility as a weapon “against the mystique surrounding art, royalty, and masculinity.” Simply by playing up their artifice, it exposes the masquerade.

Isaacson shrugs. “It was radical, in that it was outside the norm. But that was temporary—a gay aesthetic that has disappeared as mainstream culture absorbed it.”

• • •

I am just about to close the lid on camp’s coffin when I discover it has been resurrected as queer. The ivory tower is stuffed full of new takes on camp, political again but loosened from their male, gay origins. Anywhere you have gender, sexuality, ethnicity, and culture, a camp aesthetic is likely to emerge, observes Italian literary scholar Fabio Cleto, often with a new issue on its arm. Its latest companion is academe’s new interest in trash—physical as well as cultural.

Sontag saw camp as forcing aesthetes to admit their affection for lowbrow culture. “The old-style dandy hated vulgarity,” she wrote, making it clear that the delicate neurasthenic lounging on a chaise, terrified of a whiff of anything stronger than a madeleine, is far different from the sensuous camp enthusiast with a taste for the tasteless.

Now, scholars are also connecting camp to real trash. A photograph of gold glitter on a toilet draws me toward Guy Schaffer, who works in discard studies and calls camp “a mode of reappropriating and revaluing ‘trash’ while simultaneously broadcasting the ‘trashiness’ of the thing it glamorizes.” The activist artist group SPURGE stages elaborate meals of scavenged food on tables made of urban trash. This ties neatly into camp’s connection to the past: It is bent on rediscovering castoff bits of history, salvaging and reinterpreting them.

An idea occurs to me, trash adjacent: Camp is absolutely not about procreation. It gleefully ignores the biological imperative. Its projects tend to recycle, adding a little spin, rather than creating something new. Thus the Infant of Prague statues that adorned my less than devout friend Brian’s apartment; the antique Whistle and Frosty Root Beer thermometers in his kitchen. “Camp is uber retro,” he informed me, “with a little pizzazz, a little extra feather in the hair.”

Is anything retro automatically camp? It is never that easy. There needs to be a twist, a repurposing; someone has to strike an attitude toward it, exaggerate it, make it confrontational, use it to wink at the rest of us. But that is easier to do once an artifact is past its prime. “The process of aging or deterioration provides the necessary detachment—or arouses a necessary sympathy,” Sontag said. That is the point of the “passionate, often hilarious antiquarianism” Eve Sedgwick saw at the heart of camp.

As we recapture bits of camp’s history, the way the documentary Paris Is Burning did with New York’s drag ball culture and Pose does now on Netflix, will the original camp sensibility itself become camp?

• • •

A retired drama teacher, Brian Welch will give you the shirt off his back, but he will arch an eyebrow and say something caustic as he does it. I tiptoe into our conversation, remembering his apartment, many years ago, as a pastiche of Baroque, pre-Raphaelite, Warhol, and savvy flea market Americana—in other words, a model showroom for the camp aesthetic. But had he thought so?

Oh, yeah. Still tickled, he talks about the objects he gathered and how it felt to reclaim them, put his own stamp on their narratives. Then he moves from objects to performance, telling me about early Hollywood camp and the nance roles that were taken by effeminate actors long before celebs like Paul Lynde and Liberace began to toy with our notions of who they were. The nance, like the extra bachelor at a formal dinner party, came to feel vital.

“I understand that nostalgia,” Houldsworth tells me. “I feel it myself. But it is nostalgia for a specific incarnation of a phenomenon that is present in all generations. Camp is alive and well where it has always been—in the lives of the most marginalized. The femme gay boy living in rural America, the gay ball scene of the black LGBTQ community, the survival techniques of queer kids growing up in conservative Christian households.

“In some ways, I was that person,” Brian says suddenly. “I grew up in Effingham, Illinois, so it wasn’t like I was immersed in gay culture. I had tons of straight friends in high school, and sometimes I’d wonder why the hell all these butch boys wanted to hang out with me. I was that lively one, that acerbic one. A little edgy, a little sarcastic, a little bitchy.” Years later, he and other gay men would say of someone, “‘Look at him, he’s really camping it up.’ At that point, we feared being called campy; we thought that was for transvestites. But when we are together, we feel that freedom, that energy; we bounce off each other, so we’re a little more gay. It’s okay for us to say, ‘Oh my God, you are such a little fag’ to each other.” He hesitates. “As much as I love the fact that the gay subculture has almost gone away, I kind of long for it sometimes. There is a loss. Gay bars, gay bookstores—they’re all gone.”

No more private clubs; no sanctuaries with coded language and inside jokes and exaggerations of shared traits. A subculture that was pressed into being has lost its fire.

Interior designer Scott Tjaden is ambivalent about camp, hating the way it amplified stereotypes but loving the strength it gave his community, the way it bound them together and distracted them from the pain of the outside world. “We fought and hid for hundreds, even thousands of years. Now that we are more accepted, it is difficult for me to blend in with straight people at a bar. I have lost my safety net.”

I read over my notes, stare at them for a minute. An exercise in understanding camp is turning into something entirely different: a realization of the shifts gay men have lived through over the past four decades. The subculture that offered wry comfort has disbanded. Those who fought the hardest for acceptance are left feeling a little empty.

“I understand that nostalgia,” Houldsworth tells me. “I feel it myself. But it is nostalgia for a specific incarnation of a phenomenon that is present in all generations. Camp is alive and well where it has always been—in the lives of the most marginalized. The femme gay boy living in rural America, the gay ball scene of the black LGBTQ community, the survival techniques of queer kids growing up in conservative Christian households.

“The script of heteronormative life is fed constantly to queer kids and then ripped away from them, to greater or lesser degrees,” he continues. “Camp is reclaiming some element of that script, but twisting it, isolating it, amplifying it, reinterpreting it in ways that make it incomprehensible to the culture that gave it birth.”

His words are still sinking in when their tone changes sharply: “As for younger queer folks who dismiss or diminish the camp of the past, fuck ’em. The success of activists and advocates like me in making their lives less endangered does not give them the right to use this precarious safety to forget the past or ignore that queer life is still dangerous for many of our siblings.”

• • •

On iWeb, the words associated with “camp” include star, embrace, drag, over the top, fun, silly, cheesy, funny, kitsch. Is kitsch camp? Sontag allowed it as naïve camp, but I have always understood kitsch as just plain awful. Not only does it lack art, quality, and intelligence, but it is dishonest. Kitsch tries to slick a sentimental coat of paint over what is dark, negative, disgusting, evil, flawed, vulnerable, painful, or dangerous. As luminous as a Thomas Kinkade village after a Christmas Eve snowfall, kitsch is “the absolute denial of shit” (Milan Kundera’s phrase). Sometimes that strenuous denial looks a lot like camp, with its high energy, sunshine-and-lollipops fluorescence. But kitsch only becomes camp when the beholder catches the irony.

Rather than “failed seriousness,” kitsch is failed judgment, and I suspect the only way it can be redeemed is through a camp lens. What else but camp could appreciate, and recontextualize, kitsch’s manipulated sentimentality? All kitsch requires is fear. Camp requires courage.

And camp, even when we roll our eyes at its excesses. leaves us grinning. There is an immense affection beneath its send-ups. It “dethrones seriousness,” yet it must be wholehearted, Sontag insisted: “What is extravagant in an inconsistent or an unpassionate way is not Camp.” You have to be all-in, and the audience receives that vulnerability with warm appreciation, because it gives the rest of us a little more permission.

In the end, camp is a way of perceiving the world—a little off kilter, a few bubbles off plumb, freed from the need to be serious. It stays deliberately at the surface. Yet for camp to be authentic, you have to give it all you have, become a part of it completely—then wink.

The absence of bitterness is what sweetens camp into generosity. There is no judgment here, only irony, and the exhilaration of games at recess. When I think of the camp aesthetic, I instinctively think of bright colors: comic books’ lurid cyan and magenta on pulp, the TV Batman costumes’ primary colors, drag queens’ hot pink feather boas snaking through the air. “Camp’s favourite color is pink: nursery pink, sugary pink, screaming pink,” writes Mark Booth. In self-parody, he adds, camp “presents the self as being willfully irresponsible and immature”—but in such a theatrical way, and with such obvious ambivalence, that any criticism is punctured in advance.

In the end, camp is a way of perceiving the world—a little off kilter, a few bubbles off plumb, freed from the need to be serious. It stays deliberately at the surface. Yet for camp to be authentic, you have to give it all you have, become a part of it completely—then wink.

• • •

Baton Bob used to march down Kingshighway Boulevard, smack in the middle of six lanes of traffic, his skin so shiny with sweat that it sparkled like the spangles on his majorette costume. How he found one for a body that had to be well over six feet tall, I will never know. But St. Louis greeted his twirling with alarm—then puzzled frowns, or worse. Several times, he was beaten. But he just … kept … marching. Years in, he was greeted every day with delighted smiles, waves, and blown kisses.

Gender has long been linked to camp, because gender was expected to be the main expression of identity, the main way we fit in and advertised who we were. Sontag pointed to women’s clothes from the Roaring Twenties, perhaps because they were costumey and dramatic, with all that fringe and beading and feather boas, but I suspect also because of the way they toyed with femininity, simultaneously embracing and rejecting it with their pastel silks draped on flat-chested, slim-hipped silhouettes.

I think of women friends who just breathe easier in pants and sneakers, and who winced when they had to “doll themselves up,” as men used to put it, for job interviews or obligatory social functions. Gender is always an improvised performance, as Judith Butler writes, and a whole lot of drag has taken place offstage, without the applause. But was it camp when no one was laughing?

Eng worries that camp “can too often work through a series of disavowals that fortify the white gay male over and against women, transgender individuals, and racial Others.” A queer lens focuses on race and power as well as gender and sexuality, blowing the category wide open.

Today, more and more clothing lines are androgynous. Mattel makes gender inclusive dolls with androgynous features; the nonbinary “they” has won over grammarians; restaurants have stopped bothering with gender signs on the loo doors. No longer as explicitly gay, camp is liveliest in the larger queer community, most political in the transgender community, and claimable, in the broadest sense of “queer,” by anyone who cheerfully sabotages the old categories and norms. That even includes bio queens, who are biologically female but perform in super-femme drag, exaggerating what is expected offstage. Critics resent them for appropriating queer culture; defenders point out that drag queens do not have a monopoly on femininity—or the violence that can accompany it.

Writing about Hedwig and the Angry Inch, Chris Eng shows just how multifaceted discussions of camp have become. “That Neil Patrick Harris, an out gay cisgender male actor dressed in drag as a catty, sassy, campy, gender-ambiguous castrated character who speaks bluntly about queer sex, pleasure, and violence can grace the stage of Broadway seemingly signals a moment of arrival,” he notes. But if the popularity of the musical’s revival makes it mainstream, has it lost its subversive edge? Eng worries that camp “can too often work through a series of disavowals that fortify the white gay male over and against women, transgender individuals, and racial Others.” A queer lens focuses on race and power as well as gender and sexuality, blowing the category wide open.

“You can even camp up androgyny, like St. Louis drag artist Maxi Glamour, Demon Queen of Polka and Baklava, who moves camp beyond gender by performing as an otherworldly creature,” remarks Cynthia Barounis, a lecturer in Washington University’s department of women, gender, and sexuality studies. Any identity can be camp: “The only line is, are you attached to this presentation, or do you have an ironic distance from it that you are exaggerating to expose the artifice?”

• • •

On the hot sand of a beach in Australia, a four-year-old boy asks Nadya Vessey why she has no legs. Vessey tells him she is a mermaid—which gives her an idea. She asks a special effects company to design her a prosthetic mermaid’s tale, camping up her disability. Shrugging off the able-bodied norm, she is using a little creative artifice to playfully reclaim the premodern symbolism of the mermaid as femme fatale. It is a deft performance, but the media cover it as an inspirational tale—as though strangers were coming together to help little Nadya swim like everybody else.

“Never mind that she was a grown woman and already a competitive swimmer,” Barounis says dryly. Dripping with false sentiment and missing the irony altogether, the news coverage is camp itself—or maybe kitsch.

Barounis is working on a book about disability and the camp aesthetic, feeling her way into this powerful but tricky intersection. For so long, we have been afraid to laugh in the presence of disability, yet laughter has come to feel like an essential ingredient of contemporary camp. She looks at The Joker (the Dark Knight version) as a reinterpretation of Wilde’s homosexual dandy, but with a subtext that plays with disability. “Why so serious?” he teases, and each time he tells the story of his facial disability, he tells it differently. Why should someone with a disability have to keep explaining it?

The “trash” aspect of camp comes into play here, too, she adds, with people thinking of a disabled body as wasted, useless. Camp as a salvage operation.

Pushing aside her coffee mug, Barounis leans forward: “I feel like we can’t do camp the way we’ve been doing it. It needs to be reinvented.” She sees camp as an emotional state, often a therapeutic one. Camp does not have to be coated in irony, she says. We have done irony. She would prefer to recuperate sincerity. Much as she likes Esther Newton’s definition of camp humor—“laughing at one’s incongruous position instead of crying”—she is also not convinced that camp needs to include laughter. Making it obligatory can be a way to appease people in the mainstream, relieve their tension or guilt.

I know instantly what she means; it reminds me of the godawful minstrel tradition, in which you steal somebody’s humanity, then insist they sing and dance to prove how happy they are about it. Yet when she asks rhetorically, “Can we keep camp alive by making it okay not to laugh?” I have a hard time even wanting to. Laughter feels like the genius of camp. Not laughter to appease, but laughter to expose, to create enough distance for perspective. The playful deceptions, costumes, and exaggerations somehow make room for the truth.

At home that evening, I think more about what Barounis said, wondering if I am being overserious by insisting on laughter. The real genius of camp is perspective, and perspective is usually funny—but not always. Sometimes it just comes as a punch of awareness, so well-placed it knocks the wind out of you.

So maybe she is right, and camp could be redefined without the laughter. That might free us to think of the gaps along the margins, places where camp is still missing—for example, people cast to the side by poverty or displacement. When you are fighting just to eat, find shelter, or avoid deportation, you do not have a platform for self-expression, let alone the ironic distance you would need to camp up your struggle.

Laughter feels like the genius of camp. Not laughter to appease, but laughter to expose, to create enough distance for perspective. The playful deceptions, costumes, and exaggerations somehow make room for the truth.

Class has been problematic for camp, except when it was the bad taste of the bourgeois or the affectations of the rich. But race is rich with possibilities that Sontag’s predominantly white critical successors have yet to catalog, notes Scarlett Newman in “A Deep Dive Into Black Culture and Camp.” From the over-the-top caricatures of Hollywood (“Oh, Miss Scarlett! I don’t know nothin’ ’bout birthin’ babies!”) to the Detroit Hair Wars, Prince and Jimi Hendrix, Lil’ Kim, Dapper Dan’s fashion designs, shows like The Wiz, films like Blacula… This is a co-opting of artifice and glamour to resist discrimination, Newman points out. The idea is to prevent the mainstream from defining you.

That need still crops up in many, many subcultures. And our political sphere is so polarized, its extremes could look campy, too—when we find enough distance to see them that way.

“We gotta let some air out of the ball, man,” said Dave Chappelle when he accepted the 2019 Mark Twain Prize for his comedic gifts. “The country’s getting a little tight. It doesn’t feel like it’s ever felt in my lifetime.”

Camp may have to reinvent itself. We are not yet done with needing it.