The first thing the host asked me for was the story about my Aunt Ruby.

Ruby and my mother, her youngest sister, had driven from our town in Southern Illinois to St. Louis. This was maybe 70 years ago. Ruby accidentally drove the wrong way up a busy road, and as the other drivers swerved and honked their horns, Ruby leaned out the window, shook her fist at them, and shouted, “I’m from Herrin, by god!”

I have always found that funny, but when I spoke it into the mic, Phoebe Judge, host of Criminal, “one of the most popular podcasts in the world,” did not laugh. In her serious, concerned voice she asked what I heard in Ruby’s words.

Recently I learned Ruby may have fed me Uncle Wallace’s Special Eggs, which contained the squirrel brains he loved. If she did, it would have been as a joke on my mother, the kind she loved, which proved there was earthy knowledge you did not have. “Herrin, by god!” had something to do with that.

I heard many things. Ruby was always kind to me, but she scared me. Her branch of the family was wild, and even when I was old enough to remember her, she was a force in her gray beehive, cat-eye glasses, and house dresses. For a few weeks when I was a kid, my mom dropped me at Ruby’s before dawn—why was a mystery and still is. I napped, Ruby made me breakfast, then I walked to elementary school. Recently I learned Ruby may have fed me Uncle Wallace’s Special Eggs, which contained the squirrel brains he loved. If she did, it would have been as a joke on my mother, the kind she loved, which proved there was earthy knowledge you did not have. “Herrin, by god!” had something to do with that.

In the studio, I said I did not know.

“Defiance?” Phoebe breathed, feeding me the line.

I waited a long beat, not ungrateful but reluctant. Defiant meant subordinate to others, which Ruby never was. Still, I could see where Phoebe was going.

“Yes,” I breathed, unintentionally using her tone.

• • •

Criminal Senior Producer Nadia Wilson contacted me at the start of January and said they wanted to ask about the “Herrin Massacre,” the subject of one of their upcoming, biweekly shows. She called to pre-interview me and was the first to ask for my story of Ruby, which is in one of my two books about Herrin.

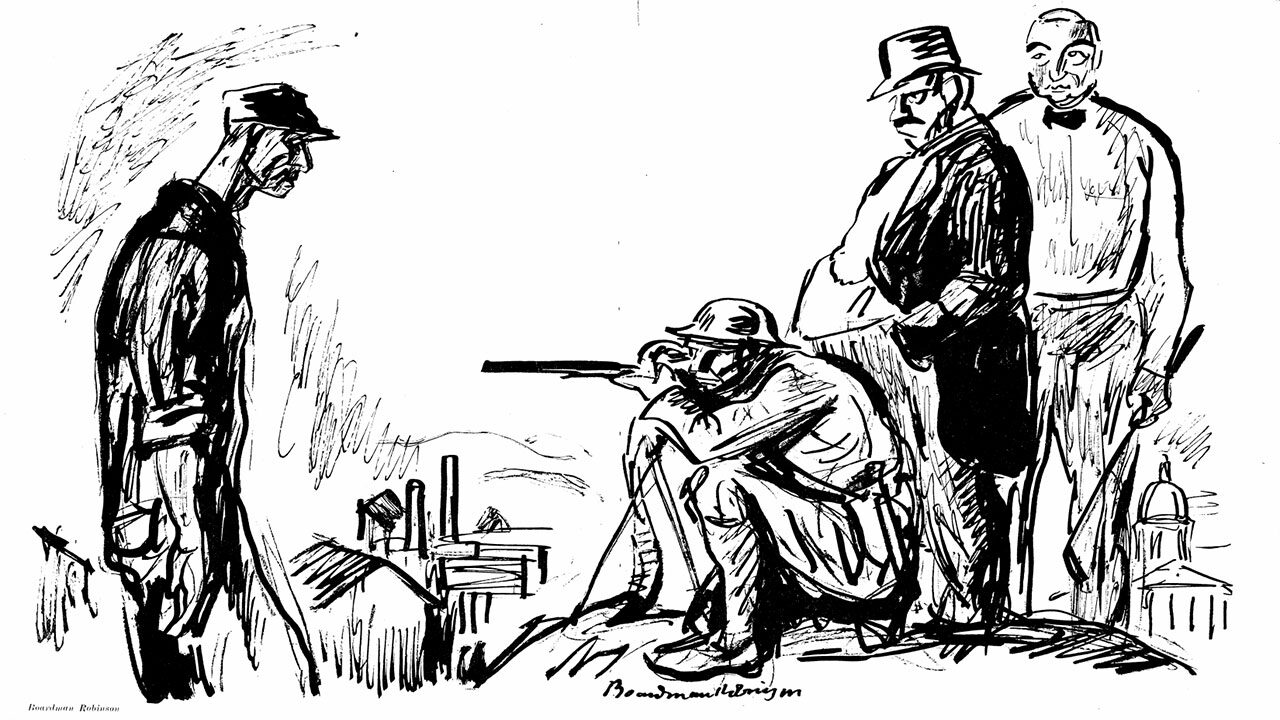

The Massacre was very big news in 1922. An absentee owner of a strip mine in Southern Illinois, going against all advisors, tried to ship coal during a nationwide strike. This set off a gun battle at the mine, where his strikebreakers and hired guards, many from Chicago, were outnumbered by union miners and sympathizers from around the region. Three union miners were shot to death or mortally wounded. After the strikebreakers surrendered, under an impromptu agreement they would be put escorted out, some in the crowd became a mob. Twenty nonunion men were murdered or mortally wounded over several hours, and their bodies put on display in town.

Industry, chambers of commerce, and media across the country denounced the town. Juries refused to convict anyone, which set off second and third rounds of denunciations.

Most of these events took place outside the small city of Herrin, which was more than a United Mine Workers of America stronghold. Labor scholar John Laszlett says that by 1919, UMWA District 12 (then the state of Illinois) “had become the largest and most powerful, as well as the most radical, district union in the United Mine Workers as a whole.” Herrin, which called itself the “largest soft coal mining city in the United States,” was the symbolic heart of that district.

The Herrin Massacre was a complex event, a culmination of decades of industrialization, extractive economies, domestic colonialism, inequity, mechanization, migration, class, race, ethnicity, and other cultural and political issues, many of which are still in conflict today.

My grandfather—Ruby’s and my mother’s father—in 1922 was a state senator who lived in Herrin, and President of UMWA Subdistrict 10 of District 12, which had 12,500 members around Herrin. He was a member of the Constitutional Convention, then in session, and was out of town during the Massacre.

I explained to Nadia I am not great on radio and was anxious about discussing something I wrote a decade ago. She was cheerful and energetic and said I would do great. She booked the first available time at a studio in St. Louis, because they were facing a deadline. (Criminal is based in North Carolina. It is independently produced but uses the studio at WUNC and is part of a “curated network of extraordinary, cutting-edge podcasts” at PRX’s Radiotopia.)

The Times says, “There are dozens of true-crime podcasts, covering a range of death and destruction. Some reinvestigate cases with reams of original research or interviews. Others resemble Wikipedia-esque retellings.” They quote the Dean of the Jandoli School of Communication at St. Bonaventure University in New York, who says podcast series can become “unscrupulous when producers develop a following and feel they ‘constantly have to feed the beast.’”

I had no reason to doubt Criminal is near the top of their genre and that the show is made with ambition. Their Facebook tagline is: “Criminal is a podcast about crime. Not so much the ‘if it bleeds, it leads,’ kind of crime but something a little more complex….”

The Herrin Massacre was a complex event, a culmination of decades of industrialization, extractive economies, domestic colonialism, inequity, mechanization, migration, class, race, ethnicity, and other cultural and political issues, many of which are still in conflict today.

What Criminal needed, I thought, was a labor historian who worked on early twentieth century coal-field violence. The canonical book on the Herrin Massacre, Bloody Williamson: A Chapter in American Lawlessness, was by Paul M. Angle, who died in 1975.

I spent those few days reviewing texts. On the morning of the interview I dropped a beta-blocker and drove to the studio in St. Louis, thinking of Ruby and the rest of my family, and the town I grew up in.

• • •

The studio engineer put me in a dirty booth by myself. I would hear Phoebe Judge over my headphones, through a crackling phone line, but the microphone would record my voice cleanly, he said.

When Phoebe came on, I did not know it was her. She was irritated with the connection, and I thought she snapped at her staff and at the engineer on my end. Trying to lighten things, I made a joke about how I might need her help and patience to get through this. She ignored me. (Criminal’s Executive Producer told me later I read the tenor of the interview wrong. I told her I would welcome hearing it in order to correct my impressions, but it was never sent.)

Phoebe asked basic questions, sometimes more than once, as if trying to get me to say things a different way, perhaps more graphically. I am not going to elaborate here on the violence; Bloody Williamson describes it in detail, and Criminal uses it sensuously. It included the humiliation, wounding, and murder, by gun, rope, and knife, of unarmed men. Like the actions of any mob, it was irrational and grotesque, and there can be no defense of it. But there are better and lesser ways of telling stories. I have come to think of the Massacre as an American tragedy, in which two old but opposed visions of our country were the seeds of conflict that may yet be our downfall.

I had chosen short, concise passages from my book for context, but Phoebe stopped me and said she did not want that. Sometimes I felt I could only answer yes or no, as if on the stand. I felt she tried to make me share in simplifications—using the town’s name as shorthand for brutality, or implying that all of Herrin’s people, and they alone, acted with one mind. (Hundreds, probably thousands, of union sympathizers flooded in from around the region.)

For context, I brought up the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, in which the Colorado National Guard and John D. Rockefeller’s private guards attacked, with machine-gun and rifle fire, a tent village of 1,200 striking miners and their families, who had been pushed out of their homes in the company town. Anti-union forces murdered 22. Two women and 10 of the 11 children who died suffocated in a “death pit” under one of the tents the Guard torched.

The brutality of detectives, mine guards, deputy sheriffs, and state militias in those years earned them a deep hatred that even in our divided time is hard to grasp. I told Phoebe West Virginia miners claimed guards “had cut the breasts off” a miner’s wife. Just before the Herrin Massacre, a miner said in a speech, “We must show the world this ain’t West Virginia.”

Mere months before the Herrin Massacre, the Battle of Blair Mountain raged in West Virginia. After years of conflict between capital and labor, the murder of the Mayor of Matewan by private “detectives” touched off “the largest labor uprising in US history.” Fifty to 100 miners, and maybe 30 coal operators’ guards, died. Later, some tried to dismiss the significance of the event by saying the miners were just “gun-totin’, moonshining, and feuding” hillbillies. But as scholar David Corbin says, “A sizable proportion of these marchers were from out of state, approximately 2,000 of them were World War I veterans, and all of them were from industrialized backgrounds.” They had discipline, bivouac colonies, and doctors and nurses.

The brutality of detectives, mine guards, deputy sheriffs, and state militias in those years earned them a deep hatred that even in our divided time is hard to grasp. I told Phoebe West Virginia miners claimed guards “had cut the breasts off” a miner’s wife. Just before the Herrin Massacre, a miner said in a speech, “We must show the world this ain’t West Virginia.” I thought Phoebe gave a little squeak of displeasure.

By the end of the interview Phoebe seemed irritated with me, or angry. I felt she wanted me to say that no one now would ever do such awful things. I said that with my age, education, and hindsight I like to think I would never have watched the terrible violence happen without intervening, as many did, let alone have participated. But if I was 19 years old in 1922, and that community and what it stood for was all I had ever known, I might have been ambivalent. After all, no one did stop it, a point she leans on hard in the episode. She did not seem to like that either, as if I was implicating her.

• • •

I brought up one of my book’s points—that there is something raw and elemental in the Herrin Massacre story that resists the commodification of, say, Al Capone, who gets themed restaurants and “bang-bang” tours in Chicago—and Judge, who is from Chicago, said Capone’s violence was just one grain of sand in the mighty beach that was a great city.

Chicago is one of my favorite places, but what an odd notion: if you have skyscrapers and great museums, some historical violence is negligible? Who decides what is negligible?

Writer Jeff Biggers is from Southern Illinois too. His Reckoning at Eagle Creek “is ultimately an exposé of ‘historicide,’ one that traces coal’s harrowing legacy through the great American family saga of sacrifice and resiliency and the extraordinary process of recovering our nation’s memory.” He told me:

“There was a toxic brew stewing in 1922—unaddressed trauma and post-war displacement, rise of mechanization … race-baiting strikebreaking tactics to polarize the communities—that led to the unconscionable. That massacre was truly barbaric, but it speaks more of the times than southern Illinois, in many ways. But this is the question I always ask the media, when … confronted with the horror of the massacre: Between 1903-1930, over 5,000 miners died in Illinois mines alone—have you ever reported on these …?”

In Reckoning he says, “[G]ruesome mining disasters rarely evoke more than a state of sadness,” despite 104,000 people having died in the mines. “Many, if not a majority of those ‘accidents’ should not be considered mishaps, but acts of negligent homicide.”

The beliefs that contributed to the Herrin Massacre are mostly long gone from the region. Accused in the first Red Scares of being “bolsheviki,” for their progressive views, the people of Southern Illinois went red with Reagan and never looked back. The coal economy collapsed before the Great Depression. Even if you were a reactionary, why condemn the entire, present-day town of Herrin?

• • •

In her “grain of sand” comment Judge also implies that all Herrin ever had was this one thing. But Southern Illinois’ mines fueled America’s factories, railroads, power plants, and homes, and our military in two World Wars.

The United States Coal Commission report after the Massacre said, “When mining began … it was upon a ruinously competitive basis. Profit was the sole objective; the life and health of the employees was of no moment.” The labor movement changed that, and not just for miners.

Herrin was, at the time of the Massacre, (one) vision of the American dream (for some). Banks and real estate boomed. It had the sort of bustling downtown we claim to pine for now. So many shoppers’ cars choked Park Avenue it was hard to cross the street. The town had an electric trolley, opera house, theaters, and good hotels. Benny Goodman and Duke Ellington played the dance hall of its amusement park, which also had an enormous saltwater swimming pool. One Herrin newspaperman (who aided Angle) ran what was said to be America’s oldest continuously-running private press.

The Criminal interview seemed to end abruptly at about an hour. The engineer said it had been interesting and that everybody did great. By the time I got into my car, I called a friend and said I was going to live to regret that. He asked why, and I said I feared Criminal was planning use my voice to re-condemn the city of Herrin. I felt sick at the thought.

That night I wrote a draft of an email to Nadia Wilson asking they not use my interview. The same friend convinced me not to send it. Instead, I wrote, “Was that usable, Nadia? Will I hear it once edited, before it posts?”

Herrin was, at the time of the Massacre, (one) vision of the American dream (for some). Banks and real estate boomed. It had the sort of bustling downtown we claim to pine for now. So many shoppers’ cars choked Park Avenue it was hard to cross the street. The town had an electric trolley, opera house, theaters, and good hotels.

Nadia replied, “Thanks so much for taking the time to speak with Phoebe yesterday! You were great. I’m afraid I won’t be able to share it with you before it posts—it’s not our usual policy, and we’re on a very tight deadline for this episode. I will, of course, share the episode with you once it’s up!”

Nine days later, Nadia emailed, “I hope you’re well. Thank you so much again for taking the time to speak to me and Phoebe about the Herrin Massacre. I wanted to write to let you know that we didn’t end up using your recording in the actual episode.

“Episodes about historical events are tough for us. We are always worried about them being too long and crossing the line into feeling like homework. We started with a very long draft, and had to make the extremely difficult decision to cut your section. Upon listening to it, we felt worried that especially the younger demographic might start to get lost in all the details.”

• • •

I did not hear the episode when it posted. A friend who is an actor said he was struck first by Judge’s voice, which he thought was overwrought. She over-pronunciated and emphasized the sibilance of “ssslitt their throatssss.”

Another friend, who taught history in Illinois, said he thought the episode “gave the barest amount of context about the Herrin massacre to smear unions as thuggish criminal enterprises.” He thought it was “bootlicking.”

Listeners’ tweets were mixed. Some expressed confusion over whether it was a racial incident (it was not). Several took the chance to condemn organized labor.

“Union workers murdering people because they want 5 dollars more a week. Lining up men and shooting them, slitting their throats if they survived the shot. Just despicable.”

“Striking doesn’t justify violence against willing workers. This was simple murder but at the end you seem to want to justify it. Disgusting.”

The world’s most insulated listener tweeted at Phoebe, “I was furious listening to this episode. It needed a warning for disturbing content. I had to turn it off, too distraught to keep listening. It’s the only episode I wish I never heard. Taking a break from you now … feel betrayed.”

I asked my first friend who the interviewee was for the episode.

“Some guy named Scott Doody,” he said.

• • •

Scott Doody’s Twitter account lists his home as Herrin. But in a region where microgeographies are important, it has often been noted (including by a former mayor of Herrin, who wanted him out of town, Doody says) that Doody is not from Herrin. One Herrinite told me Doody is “from down around the town of Anna,” known for its orchards and mental hospital, but that he did a talk-radio show for a decade at WXAN, “the home of Southern Gospetality,” in Ava, Illinois.

His show is where Doody says he discovered his passion for the Herrin Massacre. That passion would earn him notoriety and enmity in Herrin, after he launched a “quest”—“crusade I think is probably the correct word,” he says on the air—to find and dig up the Massacre victims in the Herrin City Cemetery, so he could honor the veterans among them. Despite heavy resistance in Herrin, Doody assembled a “team” for his crusade.

After a fellow history enthusiast from Herrin criticized the methods of Doody’s team, Doody said on-air, “I need to calm down and not do like I used to and drive over there and find the guy and stomp his hand ‘til it’s flat, so he can’t type anything.” He said he decided instead to demand the man retract a social media post, or he would force him to do it.

“He could figure out what he wanted to, what force it would be. I meant legally, of course,” Doody said.

“Of course,” fellow radio host Will Stephens said.

I called Will Stephens, now WXAN General Manager, and the Mayor of Murphysboro, Illinois, to get Doody’s number. Stephens told me Doody would not answer, but I might try texting him to set up a call. Doody’s website, herrinmassacre.com, has been allowed to lapse. His Twitter page, mostly unused, says, “I’m nobody.” There are Scott Doodys on Facebook, but no way to know if he is among them.

Doody does not like his old radio shows heard. “Anytime that people wanted to intimidate a talk show host, they would always ask for a ‘copy’ of your show,” he once wrote. When I asked Will Stephens if Doody’s shows were archived, Stephens told me they were all lost to “digital rot.”

It does not matter, of course, to Doody’s right or ability to write about the Herrin Massacre if he is from Herrin. Paul Angle was not from Herrin either. (Angle was a noted Lincoln scholar and author; historian of what is now the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library; and director of the Chicago Historical Society.) What does matter is that those who claim authority on historical matters are not “rascals”—what Illinois historian John Simon called unserious dealers in historical narratives, who were less than professional or ethical.

In 2013, Scott Doody self-published his book, Herrin Massacre, from “Dick’s Chicken Shack Productions.” The first half, a sort of narrative nonfiction history of the Massacre, is what your kooky uncle might write because “nobody knows” these things and “people don’t realize.”

The book has no citations, no end- or footnotes, no works cited, no bibliography, no index, and no photo credits. As a result it plagiarizes nearly everything in its first half, even if unintentionally. (The second half is more valuable, as a first-person account of finding the graves, which time had forgotten—aided, in Doody’s belief, by a hundred-year conspiracy in Herrin.)

It does not matter, of course, to Doody’s right or ability to write about the Herrin Massacre if he is from Herrin. Paul Angle was not from Herrin either. … What does matter is that those who claim authority on historical matters are not “rascals”—what Illinois historian John Simon called unserious dealers in historical narratives, who were less than professional or ethical.

The photos in his book are stretched, distorted, and printed at low resolution. The book is rife with misspellings and spells names different ways. Verb tenses go awry; his dangling modifiers put a murdered man on trial for his own death. He does not mention the national coal strike, the main basis for the Massacre, until page 49.

Worse, Doody confuses titles and roles of UMWA officers and administrators. A man named Hugh Willis is called, by Angle and most contemporaneous accounts, a UMWA State Board Member. My grandfather says in testimony that “Willis reports to [Frank] Farrington,” the District President. But Doody calls Willis the “U.M.W.A. President” and “the union president,” who “order[s] his union miners to commit mass murder.” I cannot confirm Willis was not President of the Herrin local, but Doody’s phrasing could be confused with national union President John Lewis, Farrington, or even my grandfather.

“When the United Mine Workers of America murdered the twenty one men …” Doody says elsewhere. Current scholarship has never shown the Massacre was planned by the union, or planned at all.

Doody says the victims were marched right through downtown Herrin, which is false. He says that after the Massacre, “Herrin now had two factions ready to do battle for control of the city. The U.M.W.A. and the Klan. All that was missing…. the men each side would need to lead them into battle.” This is ridiculous. The “two factions” are more accurately described as “wet and dry,” and the union had little to do with it, since its membership included both.

To pump up drama, he invents interior monologues and motives for historical persons (my grandfather among them). He uses false superlatives, calling the Massacre the “deadliest attack in American history of union verses non union labor” (sic; see Blair Mountain), and “one of the largest mass murders in American history.” (See Wounded Knee, Fort Pillow, or this long list of labor violence.)

While he does occasionally admit union miners had reason to be upset, the overwhelming impression is that the union and town are bad.

In short, Scott Doody’s writing about the Herrin Massacre is useless as history.

Doody would not care about my or anyone else’s objections. On the copyright page he writes, “If this book offends anyone…. Well, into every life a little rain must fall…. ”

But it seemed to me Criminal had adopted these stances for a huge audience, for as long as digital media lasts. Theirs is a platform the Coal Operators Association could only have dreamed of in 1922. Doody’s book is how many will learn of the event, including locals looking to know their own history.

Later, I asked Criminal Executive Producer Lauren Spohrer if they had bothered to read Doody’s book. She got angry. They had read “all the books,” she said, and spent “months” doing prep and winnowing out what could not be verified. She said they always used an independent fact-checker. She shouted that I was questioning their “journalistic integrity.” She listed the number of years each of them had been working in radio. She challenged me to name what they got wrong.

As for the quality of Doody’s book and his authority on the event, Spohrer made her voice icy.

“Do you have a PhD in history?” she said.

She had me there.

• • •

The podcast episode does have errors. It says “23 people were murdered,” which implies the strikebreaker victims, when actually three were union men killed in the opening salvos. Judge echoes Doody’s confusion over roles and titles. For heightened effect, she says “they marched the men through town, near restaurants and candy stores,” a fabrication that builds on Doody’s mistake that the grade school is “right [in] downtown Herrin.”

Judge seems to think most of Herrin worked at that little strip mine. In reality it was hardly a source of employment at all; the important thing is that it symbolized an attempt to break a national strike. She paints a dramatic picture of Herrin men sitting around watching the strikebreakers roll into town on trains to replace them, when they probably went to Marion. She confuses details of who negotiated a cease-fire for the mine and accepted its surrender, implying the union officially caused the mob action. She and Doody repeat a common story that the union intended to pay for the stolen guns, when it was just Hugh Willis talking trash, as far as we know.

The episode condemns the town by name. Judge says, for instance, some of the men imported from Chicago were workers, and others were guards who “would protect those workers from the people of Herrin”—the standard line of chambers of commerce after the Massacre, who did not mention reports of the guards bullying locals, and used the name of the town as shorthand for the region. Judge says that “all over town” people broke into hardware stores for weapons, but it happened around the region.

Judge says State’s Attorney Delos Duty—she allows it to resonate with “Doody”—believed “Herrin jurors were going to come back with a not-guilty verdict no matter what evidence he presented.

“‘It is a hopeless proposition,’ he said,” Judge repeats with all possible drama. The trials were held in the town of Marion, the county seat, and the jurors were from around Williamson County.

She reports that the Coal Commission said the town “really believed in the union,” so obvious a fact it sounds like snark. This chimes with archival tape of an old guy saying, “I don’t know who around here would condemn the coal miners. I certainly don’t. That’s what makes you union, is believing in it and willing to fight for it, it’s just like fighting for your country.” This was a common sentiment across the country, but Criminal makes no attempt to understand its importance, which is vital to an understanding of the failed trials.

By my count, about a minute and 40 seconds in the episode are devoted to context, as opposed to mere recitation of the event.

There are stories and mysteries everywhere in the Massacre, enough for a dozen podcast episodes and more than one dissertation. Who was that woman, and are contemporary accounts of miners’ wives calling for their men to kill the scabs true? How do they fit into the history of committed and sometimes violent women in the early labor movement? Who was the man (or men) who tried to calm the mob and got heckled away?

Because Doody is an unreliable narrator, and the episode is prone to sensationalism—even the music aids in it—I start to wonder about other things. Doody vividly describes a woman who did, according to an eyewitness reporter, step on a wounded man during the final hour of the Massacre, as she held a baby in her arms. In telling the story, Doody mistakes where the reporter was from and perhaps embellishes details of her appearance, which are not all in Angle’s book (though they could be in his letters, 30 years after the event, with the reporter, which are not digitized).

There are stories and mysteries everywhere in the Massacre, enough for a dozen podcast episodes and more than one dissertation. Who was that woman, and are contemporary accounts of miners’ wives calling for their men to kill the scabs true? How do they fit into the history of committed and sometimes violent women in the early labor movement? Who was the man (or men) who tried to calm the mob and got heckled away? What was the role of conspiracy theories afterward: that the national union planned the Massacre as a military action, or the one, with its whiff of anti-Semitism, that communists from Chicago infiltrated Southern Illinois’ Lithuanian population and instigated the Massacre?

Why were there two starkly contrasting Herrins at the same time—one a thriving community for families, the other violent and vice-ridden?

How did one of the most progressive regions in the country—which believed in something similar to Libertarian Socialism—shift to the libertarianism that claims to be above party politics but praises demagoguery, pushes for unbridled corporatism, and calls for the elimination of all mutual-aid services as “socialism”?

I understand Criminal is a brief entertainment. But my strongest objection to the episode is that it takes on the burden of an important and still-emotional event but lazily fails to ask what it meant then or means now, and in the process continues to damage the town’s (and organized labor’s) reputation.

In a time of inequity and destabilization, how (else) might we begin killing each other, especially given the culture of guns?

I understand Criminal is a brief entertainment. But my strongest objection to the episode is that it takes on the burden of an important and still-emotional event but lazily fails to ask what it meant then or means now, and in the process continues to damage the town’s (and organized labor’s) reputation.

The Criminal episode ends with Doody saying that Herrinites “had forgotten their history,” so some were accidentally buried “in and among” the murdered men. Going by his book, that seemed incorrect, said to gin up the story.

The irony of accusations of forgotten history was too rich. I was angry. And I was wrong about the burials.

• • •

About 2010, I noted rumors that somebody was digging in the Herrin cemetery, looking for the “scab” bodies, and that National Geographic was interested in a documentary. I eventually heard the graves were found, but there seemed to be no consequence.

As I began to write this piece, I learned more. Because the Criminal episode irritated me, I tied its failures, and those of Doody’s book as a history of the Massacre, to the dig project.

In his book, Doody shows he bulled through objections in the town to be allowed to dig—but why? “Honoring veterans” was undercut by his own mention of a VFW Commander from Chicago who went to Herrin after the Massacre and “came to the conclusion that Molkovich [the main vet Doody was interested in] had received a proper burial [and] that it was unnecessary to exhume his body and take him back up north.”

Doody claims his team wanted to give the dead a decent burial so they could rest in peace, but he admits the 16 men were embalmed, put in “ornate” vaults and caskets, and buried in orderly rows by multiple clergy. Five were soon exhumed, for families who claimed them, but no one came for the others.

Other graves in the former potter’s field were dug up too, in the search for the strikebreakers, including at least one child’s, in Doody’s account. Was it worth it?

The lead scientist on the team was referred to constantly in Doody’s book and in media as “Dr.,” though he was ABD, and as a professor, when he was non-tenure stream. Since the dig, his employment had ended with his university. His curriculum vitae included non-peer-reviewed publications, including something he wrote for Doody’s book from Dick’s Chicken Shack Productions.

Herrin native Gordon Pruett worked on regional history at SIU Press. He runs his own history press and is Program Manager of the Herrin Area Historical Society. He told me many people looking to revisit the Herrin Massacre “did not have the sensibility of the burden of being from Herrin.”

One promotional site calls Scott Doody “a Williamson County historian and principal investigator of the project,” and a retired sheriff from another county, whose rambling, unsourced biographies of victims are in Doody’s book, a “genealogist and research scientist.” Their “geologist” was, by Doody’s account, a young master’s -degree student. Excavations were by backhoe. There were accusations locally of “plundering,” “desecration,” and “junk science.” (This is what Doody, who is fiercely protective of the other members of his team, wanted to hurt someone for.)

Doody crowed, “History was made here in ’22 and then history was made here again in ’13. A group of us have made history by finding these guys.”

This seemed to be shaping up to be a story of a confederacy of rascals who used history for their own ends: The podcast had to feed its beast; Doody wanted notice; and his team saw it as an opportunity to exercise skills and technology. All around, it looked like a story about poor stories lacking in empathy and complexity.

Herrin native Gordon Pruett worked on regional history at SIU Press. He runs his own history press and is Program Manager of the Herrin Area Historical Society. He told me many people looking to revisit the Herrin Massacre “did not have the sensibility of the burden of being from Herrin.”

“Soon it will be the 100th anniversary of the Massacre,” he said. “Those unfamiliar with Herrin history and labor history will be looking for scapegoats, looking to slake their editing and broadcast thirst. Who [else] is going to pop up on the landscape?”

• • •

But it seems as if I was wrong again. Dr. Steven DiNaso did in fact defend his dissertation at Indiana State (in 2018), and now works for a private company. He is also a research affiliate at ISU, with the titles of geospatial scientist and geoarchaeologist.

DiNaso spoke with me about the science behind the Massacre dig. It is highly technical and interesting. He met Scott Doody in 2010, through a colleague at SIUC, who had invited DiNaso to Southern Illinois to do some field mapping. Doody had hired his colleague to do EMI, a noninvasive Geographic Information System (GIS) application, to find the strikebreakers’ graves, but DiNaso saw the technique would not work in Herrin’s clay-heavy soil, which is also acidic and has a high water-table.

DiNaso thought the approach should be spatiotemporal or sociostatistical. He told Doody he would need to map all of the cemetery’s 10,000 grave spaces and headstones, which is what eventually happened. Doody and DiNaso worked with Dr. Robert Corruccini, a forensic anthropologist from SIUC and former Smithsonian Research Fellow; Dr. Vincent Gutowski, a geographer who taught at EIU for nearly 30 years; grad student Grant Woods, who was actually in his 30s and a Marine; and John Foster, a former UMWA coal miner and retired Washington County Sheriff.

DiNaso spoke with me about the science behind the Massacre dig. It is highly technical and interesting.

DiNaso told me, “[T]he preliminary research we conducted in the Herrin City Cemetery was nothing out of the ordinary. Dr. Gutowski (deceased) and I had done research in at least twenty five cemeteries prior to this endeavor (since about 1990) and we knew we could locate a Potter’s Field with relative ease. […] I have over three decades of experience in archaeology, geodesy, geophysics, and applied GISci and specialize in the use of state-of-the-art technology (collectively a field known as archaeometry) where we apply the physical sciences to solve problems in archaeology.”

He said they got some “mild criticism about having to use a backhoe (ABSOLUTELY not a supporter of this) but we had specific instructions on how the work was to be carried out.”

Together, for three years, they read thousands of periodical articles and city and county records, and “produced the first accurate map of the 25-acre cemetery: sections, blocks, lots, spaces, headstones and associated interment records, some 9,600 records and counting.” This let them build “the first relational database and GIS model of the Herrin City Cemetery [with] data collected using GPS, TPS, and high-definition scanning methodologies, along with aerial photogrammetry from 1938 to present [and] made more than 260 maps and various animations.”

In the end they were able to predict where the murdered men would be and found the graves. In the process they did the City of Herrin a favor by mapping the former potter’s field and showing that families had been sold occupied plots in recent decades, so their loved ones were starting to be buried on top of, or among, what was left of Massacre victims and indigents of long ago.

DiNaso told me Doody’s book had been understandably ridiculed for lacking in conventions. He said he encouraged Doody to rework it, but he had no interest. DiNaso insisted, though, that Doody’s book was “one of the driving forces in all this.” An early version had circulated among Herrin city council members and changed the mood.

DiNaso said that as the professional who came in after Doody ruffled feathers, he worked amicably with lawyers, the state, the mayor, and even “Jumbo” Cravens, the former Sexton of the cemetery, whom Doody portrays as his main nemesis. DiNaso’s main selling point was no longer honoring the dead, but that more spaces had been sold for interments in Block 15, the former potter’s field, than there were spaces left. That was really when people in the community began to support the project, DiNaso said.

DiNaso explained to me they did 18 excavations in all. Because of the acidic soil and water, there was little left of burials from the ‘20s—a few bones, but mostly only “dentition,” some oak from vaults, or iron-staining from dissolved coffin nails. It turned out 68 percent of the plots in Block 15, an area two-thirds the size of a football field, were previously occupied. Families are now given the option to bury on top of or alongside these plots, or to receive plots in the new part of the cemetery.

He said the team, through records and genealogical work, were able to find distant living relatives of some of the strikebreakers. He said they found the grave of Antonio Molkovich, the WWI veteran for whom Doody launched his crusade, and that they have a military marker for him. He wanted me to know they had no grants or other support for the project.

Most of all, he said, “Very early on, the story and our search for the massacre victims … developed into something that was well-beyond the story of the victims. It became the story of hundreds [of] individuals who went ‘lost’ in Block 15 – mostly residents of Herrin of days long since passed….”

He said there was some interest from National Geographic along the way, but they did not want to get involved with a union/nonunion issue. The team is still considering their own documentary.

Steven DiNaso had not heard the Criminal podcast but said Doody was disappointed with it.

• • •

Scott Doody and I finally spoke by phone. His voice is very Southern Illinois, like some of my oldest friends’. It is hard not to like a rascal sometimes.

“As god is my witness, I wish I’d never gotten involved in it,” he began. He talked for four hours.

Doody said he had done internal investigations for a Fortune 500 company, did 10 years of talk radio, and now restores Pontiacs in his garage and sells them on eBay.

“I don’t like people and they don’t like me,” he said. “That’s why I did talk radio: it was just me and my producer, and the other people were on the end of a phone line. It’s not their fault, it’s mine. It’s why I work on cars.”

He is not a veteran but says said he believes in honoring those who served. He had never been to Herrin until the day he went to see the grave of Molkovich. It not only had no marker; no one seemed to know where the grave was. He went back and discussed it on his show.

When I said I was a veteran and knew no veteran who would have launched his crusade, he admitted his reasons changed quickly.

“I just don’t like being told no,” he said. “None of this would have happened if [the Mayor of Herrin] hadn’t called me at the studio. For that guy to tell me, Don’t come back or I’ll have you arrested…. All I was trying to do was place a marker. It lit a fire under my ass. He told me no, and I’m too stupid for that.”

He had read Paul Angle, which excited him enough to visit archives around the state, including Angle’s papers in the Chicago Historical Society. Doody told me Angle “plagiarized the newspapers of the day, word-for-word verbatim what they said. Angle didn’t know anything. He tried to cash in on Southern Illinois history. Hell, he was from Springfield.”

Doody said he pored over the 800-page State House Hearing report (Herrin Massacre Investigation Proceedings, 1923) but still learned nothing about the location of the Massacre victims, which should have been “the obvious question.”

He said he wrote his book as he would speak on his show. I told him DiNaso said he pushed Doody to edit it. Doody was unrepentant, even defiant.

Doody said he pored over the 800-page State House Hearing report (Herrin Massacre Investigation Proceedings, 1923) but still learned nothing about the location of the Massacre victims, which should have been “the obvious question.”

“I’m an arrogant bastard if I think I’m right,” he said. “I told Steven, ‘I’m not gonna put any notations in there, I’m right. If they [readers] want to know my sources they can go do their own research.’ We agreed to disagree on that. I told Steven, ‘I’m not quoting the New York Times, I’m not plagiarizing anybody. I’m telling a story, and they can pay their own money to read [source material] on library screens.’ I don’t want to call it a novel. But there’s nobody to quote, no notations to make. It’s all from newspaper accounts, and me talking to old people. Most of the first half is the House report.

“I asked Steven, ‘What do you want me to do, cite the House report? People can go find it on their own.’

“I’m not bragging, I’m my own source material. It’s all my own opinion of thousands of newspaper reports I had read, witnesses—old folks in Herrin—and trips to [archives].”

“I’m more of an entertainer than a writer, but I think what I’ve written about the Massacre is right,” he told me. “I will brag that what I wrote about the Massacre is as close as you can get to being there. There are only three people who are experts on the Herrin Massacre: me, DiNaso, and [former Sheriff John] Foster,” he said.

He said he wrote an early version of the book to overcome resistance. “If words are on paper they must be true,” he said. “I wrote the book in a hurry, and it shows it. But right away, [Herrin] Councilman [Bill] Sizemore contacts me.”

• • •

Bill Sizemore told me, “It was a pretty sensitive matter. Think about Herrin and its connections to coal and what was going on in the ‘20s, and the mine out there and what they were trying to do.”

When Doody came to town, “I was an alderman, and Chairman of Public Works, which takes in cemetery issues. I had no idea what had taken place, until a personal friend of mine’s parents were going to be buried on top of others, and my friend called and said, ‘Can you see if this is true?’”

“When I see the scientists, and they have universities that support them…I made it public that it needed to be looked into and needed to be corrected. Vic [the Mayor] and I got loud in a couple of council meetings. The council backed me when I said let’s start exploring to find out.

“It was gratifying we could locate those victims. I was able to get some funding together to have a monument with their names and birthdates. There were some war veterans in that plot. For what it’s worth, I feel pretty proud we were able to get that taken care of.

“My purpose was to make a good thing out of a bad event, and make sure no more burials took place in those areas.”

• • •

Doody told me the team’s passion was “a sickness, like people being on dope.” He spent $2,000 on radar, thousands more in gas, and put in thousands of hours, as did DiNaso.

“I saw things in that cemetery I shouldn’t have seen,” he said. “I’m not traumatized by it, but that’s why I dropped off the radar. I’ve only been to the cemetery twice since we finished.”

Doody said he was not anti-union because of the Massacre. He does not even believe it was a union/non-union issue. To him, the cause was just “anarchy,” though he also said John L. Lewis told Hugh Willis to go kill those men. He could not tell me how he knew that.

“I blame law enforcement,” he said. “It’s hot by-god 1922 in June. I’m law enforcement. When somebody walks a guy up my street with a rope around his neck, I’d say, OK boys, you’ve had your fun, you got your point across. But nobody did anything.”

“I saw things in that cemetery I shouldn’t have seen,” Doody said. “I’m not traumatized by it, but that’s why I dropped off the radar. I’ve only been to the cemetery twice since we finished.” He said he was not anti-union because of the Massacre. He does not even believe it was a union/non-union issue.

He said the mine owner should have hired real Pinkertons, who would have won the conflict, “instead of the chickenshit Hargrave Detective Agency.”

As for the Criminal podcast, “A producer called me, went on and on about it. I avoided them for two months. Now I want to put it behind me. The episode was a damn lie, a dog-and-pony show. They butchered it. I said things she didn’t care for or didn’t run with.

“Something else that burns my ass: I ended with good news to this story. The town came together, erected a huge marker, and embraced their past, as dark as it is. This ended as a good-news story, I told her.”

“Herrin can point to the cemetery now, they did a nice job with it, it is closure. The people of Herrin are good people.”

• • •

Jake Priddy’s family has lived in Herrin for decades. As a child his father was taken to see parts of the Massacre, still in progress.

“People say, How could that happen? For crying out loud, look at the details, they’re still happening today,” he says. “Human nature doesn’t change. Desperate people do desperate things.

“The Information Age is an interesting thing. On the one hand, it sort of exacerbates the tendency to condense everything to something brief and simple. At the same time, for a thoughtful person interested in actually finding something out, we have more info at our disposal than there’s ever been. A two-sided coin there.

“My thing is that history is taught as if this thing happened on this day. But history is a continuum. There’s not a lot of things you can effectively isolate and say they were unrelated to something else.”