After college, my dad and two of his Washington University buddies started an ad agency. By the time I was born, Batz-Hodgson-Neuwoehner was tossing out catchy little ditties like “I’m a meat man, ma’am, and the meat man knows: the finest meats, ma’am, are MAY-rose.” Those were innocent times: consumers were still just customers, and they still trusted advertisers’ claims and smiled at their goofy rhymes and obediently bought their products.

Only eight months old when my dad died, I had zero interest in his art of persuasion. Babies need not be persuaded of anything, except perhaps to hush. Advertising only became mildly interesting when my handsome young uncle went to work at Gardner Advertising and wound up in a photo shoot, posing for a black-and-white photo with a highball glass in his hand. The Scotch ad ran in Playboy, its coolness undeniable. Then I begged for stories, suddenly thirsty for a world I would have seen firsthand if my father had not suffered a stupid heart attack on the golf course.

BHN grew fast, I was told, but the early years were the best, full of practical jokes, frantic brainstorms, three-martini lunches, and hard, tension-spiked work that ended early on Friday when the execs snuck out of the office to, yeah, play golf. All very Mad Men, and hard for me to picture in family-friendly St. Louis. Yet when the show was released, my mom pronounced it accurate—all the way down to the hors d’oeuvres she served at parties.

Persuasion has always run close to propaganda, and all of it is manipulative—as are our friends’ enthusiasms and the habits of those we admire. Creating an ethics of influence would require psychoanalyzing the nation.

How did our bland city become a hot spot for national ad campaigns? Overhead was low, flights were easy in any direction, and smart, creative talent was abundant. Between the two world wars, Winston Churchill himself, speaking at an international advertising conference, pronounced the St. Louis Ad Club “far ahead of other cities.” By midcentury, the Midwest was the obvious place to study middle America.

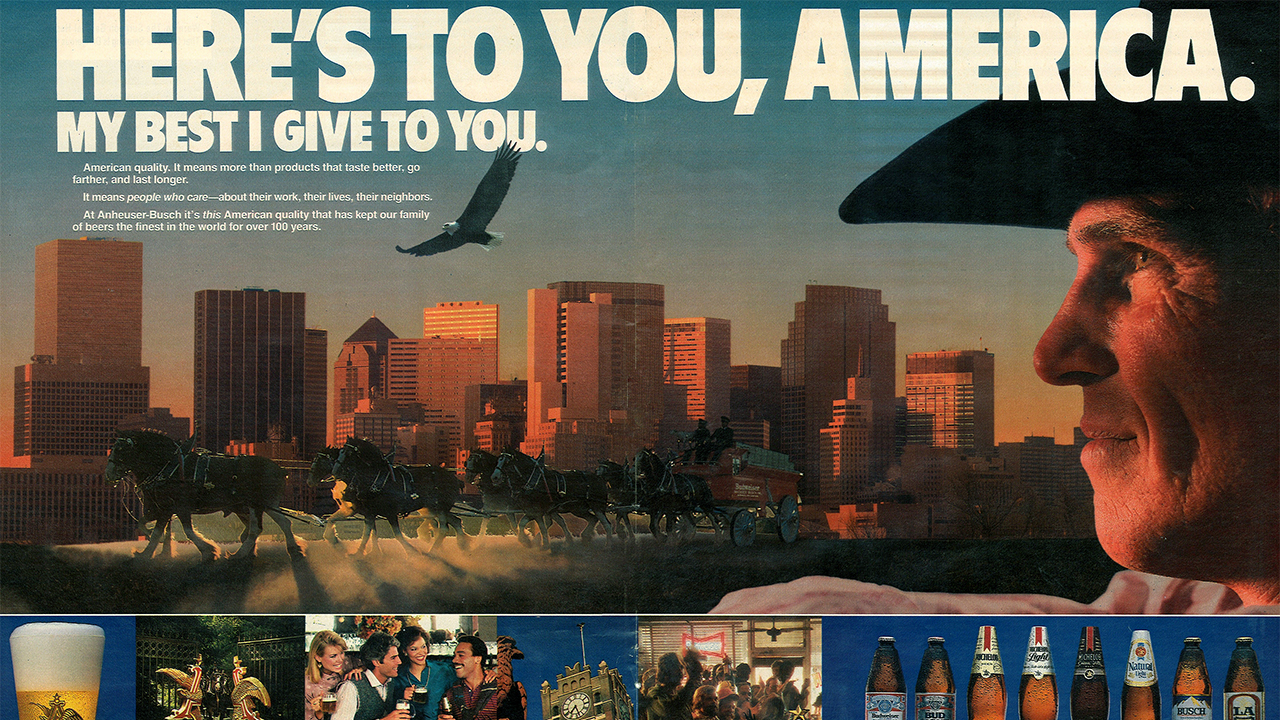

For the city’s two biggest firms, D’Arcy and Gardner, some of the splashiest and most profitable accounts in this golden age (setting Coca-Cola aside) were Jack Daniels and Anheuser-Busch. Clever copy and gorgeous images poured forth, influencing first the nation’s drinking habits, then the world’s. I type that sentence queasily. How many drinking problems did those ads encourage? Were advertisers responsible for the long-term effects of their persuasion?

The qualms are mainly for show—me proving to myself that I have a conscience. The truth is, I drink whiskey and beer, and I love clever ads and would never want them censored. The use of spirits is an ancient temptation; ads only differentiate the brands. Besides, not much is bought and sold without collateral damage—my father’s corny Mayrose meat man probably induced a few heart attacks all by himself. Am I rationalizing? Persuasion has always run close to propaganda, and all of it is manipulative—as are our friends’ enthusiasms and the habits of those we admire. Creating an ethics of influence would require psychoanalyzing the nation.

If we could throw the country on the couch, though, booze ads would be the place to start. They tell quite a story.

What a Country!

In 1880, only gaslight flickers. What shatters nerves is not the flash of digital stimuli but the deafening role of industrial machines. Life’s pace is picking up. The ads in newspapers and magazines are not yet accelerants; instead, they are soothing. Like housewives chatting over the back fence, they list all the wonders of a particular product and thus remind you of the wonders of this young nation. You, the potential customer, pore over long, grandiloquent descriptions and think perhaps you should buy this or that marvelous, miraculous thing. Then you close the newspaper and set it aside.

In the next decade, ads tiptoe off the page. Catchy slogans sneak earworm promises into your brain. Simple pen-and-ink product sketches turn into elaborate illustrations, heavy on the symbolism. Witness a 1908 newspaper ad for Budweiser, slogan: “The king of all bottled beers.” A heavily muscled man, shirtless in overalls, threshes wheat: honest American sweat in the land of plenty. “Six Thousand Men are employed by the Anheuser-Busch Brewery,” the ad reads, adding social capital to machismo. You, the customer, are not even mentioned. But you know that if you buy the beer you will champion the values of your glorious nation.

If we could throw the country on the couch booze ads would be the place to start. They tell quite a story.

Skip ahead to the 1910s. Now the stories are more personal. Happy marriages (those in which the little woman waits on her man) dangle from ad after ad. For Pabst Blue Ribbon, a smiling wife pours “the evening glass of cheer” into her contented husband’s pilsner glass as he reads “his” newspaper. The man of the house must know the goings-on in the larger world. But if you are his wife, Pabst knows you will peek, swipe your hands dry on your apron, and pour him that glass of cheer.

Persuasion ends there—but not for long. If advertising has the power to improve marriages, boost patriotism, and cheer us up, what else might it fix? In 1928, Edward Bernays announces that “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.” Illustrations take on a Norman Rockwell feel—painterly, vividly colored, finely detailed slices of everyday experience. Maybe you tear out a few and frame them. Years later, you will smile at how pleasant the past was.

“If I were starting life over again, I am inclined to think that I would go into the advertising business in preference to almost any other,” Franklin Delano Roosevelt is quoted as saying. “The general raising of standards of modern civilization among all groups of people during the past half-century would have been impossible without that spreading of the knowledge of higher standards by means of advertising.”

In the new ads, you, as both customer and citizen (the roles by now inextricable) are the star. Compliments are strewn to flatter and indulge you. “I see you have excellent taste,” says a fortune-teller in a 1937 ad, gazing into a crystal ball filled with Budweiser. “You deserve a vacation every day,” Anheuser-Busch tells a 1939 businessman dreaming of fishing. Oh, pshaw, you think—yet you want to agree.

If advertising has the power to improve marriages, boost patriotism, and cheer us up, what else might it fix? In 1928, Edward Bernays announces that “the conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society.”

Then the edge sharpens.

In 1943, as war blasts Europe and you struggle with the weeds in your Victory Garden, D’Arcy creates an ad about a wife who could not cook or grow vegetables until “the help left and couldn’t be replaced.” She studied up, and “now her dinners are a delight.” The point, tucked in at the end, is “the added satisfaction coming to all wives who have learned that cold, foaming Budweiser makes all good foods taste better.” But the underlying message—keep your man happy—hits harder than that 1910 “glass of evening cheer.” Over three decades, the approach has grown sly, crafting a full narrative that plays on wives’ insecurities and their husbands’ dreams. You hurry to buy more seeds and pore over recipes, realizing that without concerted effort, you might not measure up.

The same hint shades a 1950 Schlitz ad that shows a husband putting a proprietary arm around his wife, who is weeping over a blackened saucepan. “Don’t worry, darling,” says the condescending bastard, “you didn’t burn the beer.”

Midcentury ads raise male insecurities, too—but soothe them immediately. No inadequacy is suggested, no self-improvement required. A 1952 Budweiser ad shows a bridegroom, a Clark Gable lookalike clad in white tie and tophat. “Just as ‘the right girl’ comes along,” the ad assures men, “sooner or later the right beer comes along.”

Consumerism works best when its audience is unsettled, in need of relief.

For women, advertising seldom reassures. Back in 1929, Middletown was already describing ad copy that “points an accusing finger at the stenographer as she reads her motion picture magazine and makes her acutely conscious of her unpolished finger nails.” Midcentury, a new role solidifies: advertising as the visiting aunt who, in the guise of helping, always manages to slide in a snide remark. You, the customer, have a sour stomach, eat too much, grime a ring around your collar. Certain products will civilize you, make you fit for company again. Marshall McLuhan dryly observes that “democratic freedom very largely consists in ignoring politics and worrying, instead, about the threat of scaly scalp, hairy legs, sluggish bowlers, saggy breasts, receding gums, excess weight, and tired blood.”

The shift in approach is practical as well as Machiavellian: mass production is glutting the market with stuff to buy. It is no longer enough to marvel over a product; you will have trouble distinguishing it from its competitors. But when an ad mortifies you instead, it leaves you desperate to fix your flaws with that now-memorable product. “Buy me and you will overcome the anxieties I have just reminded you of,” sums up Columbia University journalism prof Michael Schudson. Consumerism works best when its audience is unsettled, in need of relief.

Plop, Plop, Fizz, Fizz

By the seventies, peak of the golden age, St. Louis is crammed with geniuses. Gerry Mandel is one of them: he writes extraordinarily effective ad copy at Gardner and D’Arcy. He has only radio, TV, billboards, and print to reach his audience. His ads are straightforward problem-solution, but clever; concept is everything. He and the art director spend hours brainstorming—no tech involved, just a big sketchpad on the art director’s lap to catch the ideas they toss back and forth.

A dozen years later, in 1983, TIME magazine waves aside its “Man of the Year” and puts a computer on the cover: “Machine of the Year.” “This,” mutters Mandel, “will change everything.” Soon the brainstorming sessions take place in front of the art director’s computer. How real can they make the ad look? How eye-catching can it be? As visuals take precedence, concept matters less and less. No longer is the transaction straightforward, either. Advertisers are practicing a new alchemy, one that turns existential longings into concrete desires. Buying this product or service will ease your restlessness and uncertainty, fulfill your secret yearnings. Because what you buy does none of this, the approach works perfectly, each purchase leaving you wanting more.

Ad copy celebrates your dreams. You are not flaky, stinky, and grimy after all. You are wonderful. Your life shines with possibility. Which is a good thing, because the world around you has tarnished. With the Vietnam War lost and cities set on fire, American morale has sunk low. Charlie Claggett, the son of Gardner Advertising’s legendary CEO, works at D’Arcy, where he is determined to make his own mark. He does it with a brilliant slogan: “This Bud’s for you.” Celebratory and patriotic, the new campaign captures the blue-collar market from Miller with heroic montages and stirring music. “To the guys who take all the heat for us,” reads an ad showing members of the military. “For everyone who cuts the big jobs down to size” shows a group of lumberjacks. The subtext is not so different from that 1908 ad about 6,000 men reaping the harvest…except the ad is not about the product, the process, or the nation. This ad recovers the larger context but trains the spotlight on you, the customer, defined as any guy who works hard, drinks beer, and wants to feel proud of himself. A-B shoots past Miller in the 1980s beer wars.

Next, Budweiser switches to a lighthearted approach, using Spuds McKenzie, the original party animal. The sense of fun ratchets up. You look forward to the ads, laugh about them with your friends, wish you had as much fun as A-B thinks you do. By 1999, Bud has the famous “Whassup” commercial, showing friends calling each other and drawling goofy “Whassssssssuuuuuuuup?” greetings as they drink beer and watch the game.

The feel is not so different from a 1946 Budweiser ad that shows boys shucking off their clothes and diving into a swimming hole. Male camaraderie is held up, and if you are a lonely, overworked guy who never sees your friends anymore, the message hits home. Compare a recent Miller Lite commercial: “You could search the ends of the earth and never find a bond so pure.… a thousand shared chicken wings, a million shared memories. No other crew you’d rather spend the rest of your Miller Time with.”

Nostalgia always works. So does sex, especially in the Sexual Revolution’s wake. Seventies ads are demure porn. A 1974 Canadian whisky ad shows a curvy blonde in a black velvet halter dress and asks, “Have you felt Black Velvet? Do it soon. It’s too good a feeling to miss.”

In the eighties, as masculinity frays and clouds, booze ads try to shore it up. Claggett directs a beer commercial with construction workers eyeing an attractive woman as she walks past. Spontaneously, one of the guys hits his forehead and falls backward into the fountain. Perfect! Other ads show prizefighters, farmers, fishermen, rodeo riders. Or women in bikinis lying on Budweiser beach towels.

Seventies ads are demure porn. A 1974 Canadian whisky ad shows a curvy blonde in a black velvet halter dress and asks, “Have you felt Black Velvet? Do it soon. It’s too good a feeling to miss.”

Celebrities join the effort. “Water’s for flowers. Dickel’s for drinkin’,” Claude Akins announces—and in smaller type: “The two don’t mix.” This, then, is how to be a real man, a country-cowboy man: drink your whiskey straight up. John Wayne appears on a Budweiser ad; Sean Connery on whiskey. Jack [Daniel’s] is introduced as “Sinatra’s right hand man.” (Fair enough; he was buried with one of those square bottles cradled in his arms.)

Even when your idols are glossed, though, the ads are really about you. A Modelo commercial talks like the most inspiring coach you ever had: “There’s satisfaction in sacrifice. It is filled with blood, sweat, and tears. Knowing that you left it all on the floor, and never threw in the towel—well, except to clean up the mess. Giving it all up for your team is worth every drop.” The camera follows not the football players but the fans, cheering, sweating, anguished, rejoicing, and jumping up in triumph, beer sloshing out of their cups or cans.

Beer makes you your own hero.

Jack Daniel’s Is America

Jack Daniel’s is the most popular American whiskey of all time. Even in the early 1900s, its ads appealed to tradition, calling it “a pure straight whiskey, the kind your father and your grandfather and his father drank.” Jack, the copy promised, “will stand the test.”

Its campaigns sure do. In the 1950s, after a few hokey ads with men jovially clinking glasses under the words “Man to man, the good word gets around,” Gardner launches Jack Daniel’s now legendary Postcards campaign, which will set a record by lasting four decades. An early creative brief explains that “Jack Daniel’s Country is well-rounded hills, untroubled skies, elm shaded lanes and long shadowed cattle astandin’ in the corners of meadows. It is old families and flowered front porches. Dirt roads. Screen doors. Sunlight slanting on weathered barns. Cowbells that are rung when it’s time for dinner and fresh baked pies simmering in the kitchen.”

Homespun Americana—slow, steady, solid—that is what they are selling.

Ted Simmons starts writing Postcards copy in 1967. He travels often from St. Louis to the Hollow, where he sits by the hardware store’s potbellied stove eavesdropping on farmers and whiskey makers to find out what they would say.

Just before the Postcards begin, a print ad’s antique photo shows ducks, seen from the back, waddling toward the distillery: “Life is leisurely in Lynchburg, Tennessee (pop. 399).” Here is the lyrical Postcard version a few years later: “A squeaky grain wagon bringing a neighbor’s grain to Jack Daniel’s Hollow is about the only thing that ever stirs up our ducks. What attracts ducks to the Hollow is our spillings of fine grain and cool, iron-free water. But what keeps them here is our quiet, unhurried way of life.”

Ducks waddling, cows astandin’, oldtimers playing checkers—the postcard stories emphasize mellowing whiskey “to a sippin’ smoothness,” and the honest patience this requires. Blood pressure drops just reading the fine print. And the type is deliberately small, letting each man think he is one of the rare few who bother to read that little story and get in on the secret.

Ted Simmons starts writing Postcards copy in 1967. He travels often from St. Louis to the Hollow, where he sits by the hardware store’s potbellied stove eavesdropping on farmers and whiskey makers to find out what they would say. His charge is to show that “Jack Daniel’s is America. America is Jack Daniel’s. A magical, mythical place that beckons American men.”

When Gardner is bought, Simmons keeps the Jack Daniel’s account and forms the Simmons Durham agency. The Postcards continue. But in 1995, “a decision is made,” Simmons says, the careful passive voice making it clear this was not his choice, “to do something that’s a shorter, faster read.”

Emphasis shifts from the Hollow to the bottle: easy to focus on, a quick read, a label you will remember when you shop. Copy is shorter and punchier, masculine in a more performative way. “How men bonded—back before they knew they were supposed to,” it might read, or, “At some point you just know who you are. For us, that was 1866.” Soon the ads have shifted from seventy-five-word stories to seven- or eight-word quips. “How the good old days earned their reputation.” “Improving guitar solos since 1866.” “In any bar in America, you know someone by name.” “The shot served round the world.”

The agency is no longer “just making ads,” Simmons realizes. They have jargon now. They ponder “brand essence.” The persuasive marriage of art and words—the twentieth century’s most condensed and compromised art form—is becoming a dubious science, measuring test groups’ sweaty palms, compiling demographics, hunting trends, conducting brand trials.

But there is still cleverness, still a strong and seductive voice. Once the old emphasis on history is brushed aside, the ads focus on the fun places where people drink, the football games and rock concerts and outdoor adventures. Jack is “survival gear for the frozen tundra.” It is “served in fine establishments and questionable joints.” Subtext: it remains quintessentially American, aspirational yet scornful of snobs.

A 2002 commercial of short-story caliber, shot in moody brown tones, shows a band panicking because their bass player has not shown up. A fry cook in the kitchen—older guy, bald, tough looking—hears a band member call out to the crowd, desperate: “Does anyone here play the bass?” He steps out of the kitchen and picks up the guitar, unsmiling. They look startled—and dubious. And then he starts playing, and the sound is amazing, and the drummer grins and gives him a strong beat, and you feel yourself relax and realize your muscles had tensed. In thirty seconds: a refutation of stereotypes. A redemption of unglamorous work. An act of rescue, a salute to risk, a fated coincidence, a fast-forged sense of community.

A brilliantly minimalist 2005 print ad pulls everything together—the Americana, the sense of history, and the new irreverence. Denim overalls hang on a sunlit clothesline, wafted by a breeze. The type reads: “Paris got fashion. We got whiskey. (Sorry, Paris.)”

Fewer words, stronger juxtapositions, instantaneous camaraderie. But why, with a substance so desirable, seducing us with the promise of ease and, drunk in excess, oblivion, do the makers of booze even need to be this brilliant?

Because they have to sell a particular brand, yank it out from the others, raise it up from the mosh pit. People want to be more than “a Scotch man” or a woman who “likes her beer.” They want bartenders to nod at the assurance of their order, loved ones to fondly remember their tipple at the holidays. In short, they want to brand themselves—a practice recently named but not recently invented. Someone who drinks a particular kind of beer or whiskey takes on the attributes of that particular beverage. “Integrity, straightforwardness, respect for tradition, good-naturedness, humility, pride, belief in hard work,” in Jack’s case. Advertising becomes a matching game, aligning attributes with your aspirations. Who do you want to be—one of the six thousand men? The cook who saved the day by playing bass? Their drink can be your identity.

Here is how the Jack Daniel’s consumer is profiled, in-house, in 2015: “Drinking it isn’t about being someone I’m not, it’s about being who I am. And telling others who I am without saying a word. My granddad drinks Jack. So do rockstars. What they have in common is that they don’t fit any mold except the one they made for themselves.” (And, of course, the one being profiled.) “In a way, drinking Jack is like staying true to who I am and moving forward all at once.”

In his [my father’s ] day, mass media was powerful but kept things simple. Then it exploded, and what hits us now is shrapnel.

Which is quite a trick. The profile goes on, making life a grand adventure and its drinker brave and Jack Daniel’s a whiskey strong enough to just be itself. The quality of the product, once an ad’s sole topic, is barely mentioned. Booze advertising is now your bro, urging you to live your best life.

“I’ve always wanted to do that,” says a bartender after sending a glass sliding all the way down an impossibly long bar in Jack’s 2020 Make It Count campaign. “I’ve always wanted to do that,” says a young woman (females are now targeted, too) after ordering “one of everything” at an elegant restaurant. “I’ve always wanted to do that,” says another young woman after seeing that her boss is calling and throwing her phone in the lake. The idea? To “choose boldly and with purpose every day, much like Mr. Jack did throughout his own life.”

These ads are more inspiring than a therapist.

Under the Influence

You know how some friendships can get weird? The bro who always had your back is now stalking you. Mass media is gone, and with it all chance of mass consensus. Advertisers have to capture your data so they can whip up your particular desires. Search for something, and your first results will come from companies who bid for that spot at auction. Scroll down and click, and an ad will pop up or a video will blare. Even if you install an ad blocker or cover your eyes and ears, “you’re being touched hundreds of times a day,” notes Farrell Crowley. Based in St. Louis, she does media planning and buying for the o2kl agency in New York.

“Search is the ultimate converting platform,” Crowley tells me, “because you are actively looking for something,” and all those influencers are out there waiting. If you go looking for, say, “the top influencers on TikTok who teach you how to do your eye makeup, you are already way more engaged.”

Sometimes I search aimlessly just to see what the internet will throw back at me, decorating every page with ads for what I seem to want. What would my father have made of this weirdness? In his day, mass media was powerful but kept things simple. Then it exploded, and what hits us now is shrapnel.

Influence, the word of the decade, is scattered across a billion screens and experiences. Diversification lets marketers dice and sort their audience, but is so much variation diffusing their message’s power? “It all seems kind of thin to me,” remarks Claggett, who was chief creative officer when he left D’Arcy. Ads shapeshift—quick video blips (six to nine seconds is the estimated attention span), influencer demos, Instagrammed events, marketing ploys. Companies host street parties. Odd partnerships form. Why is Progressive Insurance hawking the Barbie film? How did we go from Game of Thrones to Budweiser’s “Dilly Dilly” commercials?

Once, we could turn the page or close the magazine. For TV, the tradeoff was just as clear: sit through commercials, and you could watch for free. Nobody knew who you were or what you looked at or whether you then bought. Now ads live inside your phone, so you carry them with you everywhere. They interrupt your podcasts and light up the sides of buildings and blast from your gas pump or get stuck to your supermarket cart. They are painted on cars, papered all over stadiums, embossed on uniforms. Look down: there are Burger King logos on the escalator steps.

We live in a 360-degree brandscape. A Pabst ad worthy of SNL hawks its new “In-Home Advertising,” promising to pay you to wallpaper and carpet your home with Pabst Blue Ribbon ads. The exaggeration would be only silly, had I not just seen a cow with a web address stamped (branded?) on its flank.

How did we wind up on the set of Idiocracy? First, the sellers lost our trust. You can only entertain so many empty offers of dreams-come-true, so many visions of yourself as sexy and heroic, before you turn cynical. Sellers fought that cynicism by barging in from all directions, which felt even more invasive and even less trustworthy. Soon we were numb. When one of her friends swore she never responded to ads, Crowley raised an eyebrow: “I’ve seen you buy things off Instagram!’”

“Oh,” the friend said. “Right.”

Once, we could turn the page or close the magazine. For TV, the tradeoff was just as clear: sit through commercials, and you could watch for free. Nobody knew who you were or what you looked at or whether you then bought. Now ads live inside your phone, so you carry them with you everywhere.

The behavior is easy to lose track of because it feels less like shopping than self-improvement. The blurred, impulsive acquisition of stuff is just an action step toward our real goal. Ads are now in charge of reshaping our lives. They asked for it, manipulating themselves into a corner by convincing us that products had magical qualities that could change our lives. We stopped wanting to know about the products and wanted to hear more about ourselves instead. Now, says Simmons, “the general belief in corporate America is that everyone is more interested in their own life” than in any particular product. But how is an ad campaign supposed to overlap with the dreams of a million different personalities? All Johnnie Walker can say is “Keep walking”—move forward, better yourself, push your boundaries. The slogans and concepts are as big, vague, and schmaltzy as motivational posters.

Simmons, Claggett, and Mandel were gods of the golden age. They dealt out ideas like poker hands, wrote lines that stuck and jingles people can still sing half a century later. Today’s ads disappoint them. Either they are aimed at the young and so fast-cut and abstract that their message is insubstantial or incoherent, Mandel grumbles, or they are “old people holding hands in the sunset because of the pharmaceuticals, and all you’re hearing are medical disclaimers about how this product could kill you.” Radio ads, once the test of cleverness, are just “boring and shouty.” Visually, “it’s nearly impossible nowadays to wow people,” remarks Elliot Wilson of The Cabinet, “because we’re just overrun with visual stimuli.”

Once you strip off the tech, though, how much has changed? Capitalist markets operate the same way they did three centuries ago, right?

“Not in terms of penetrating every nook and cranny of the culture,” says Cornel West. “Not in terms of penetrating every nook and cranny of the psyche. Not in terms of penetrating every nook and cranny of the soul. We’re dealing with commodification on steroids.”

How does inhaling influence 24/7 affect us? All this custom attention, invisible eyes trained on who we are and what we want. I wish I felt flattered, but more often, I feel besieged. Numbed. Sick of swatting it all away. I know that, like Crowley’s friend on Insta, I am often swayed in spite of myself. But I am also becoming, as are you, “ad blind.” Our overloaded brains block the ads’ very existence. Ask me if an online publication I visit often has display ads, and I will hesitate. I have stopped consciously registering them.

“You are more likely to complete Navy SEAL training than click a banner ad,” notes Adpushup. One research team logged a click-through of now less than 0.1 percent. And yet, like the old obnoxious direct mail and absurd telephone and door-to-door solicitations, banners and pop-ups and TV commercials persist, outlasting both their welcome and their efficacy.

We do still register the most creative ads. And Bernays was right: they remind us of the values of our time. Or they negotiate those values. After this spring’s kerfuffle over transgender influencer Dylan Mulvaney drinking a custom can of Bud Light, the creatives for Anheuser-Busch InBev (who are no longer St. Louisans) threw together a new ad in two weeks: a Clydesdale galloping past the Arch, through a downtown where two guys clasp hands in a macho way, then across fertile farm fields and through pounding surf. American maleness, restored.

Clichés, it seems, still resonate. But do they lure customers or just reinforce ideology? Has the evolving, ever more sophisticated art of influence changed our drinking habits?

“You are more likely to complete Navy SEAL training than click a banner ad,” notes Adpushup. One research team logged a click-through of now less than 0.1 percent. And yet, like the old obnoxious direct mail and absurd telephone and door-to-door solicitations, banners and pop-ups and TV commercials persist, outlasting both their welcome and their efficacy.

The ads of yesteryear spoke to customers who had settled down and made some money. Now, a lot of advertising is “cradle to grave,” and booze ads aim hard at the young, who somehow already have money in their digital wallets. The plan is to convert these young drinkers, dazzled by choice, to brand loyalty. Studies do show that young people, who are especially vulnerable to influence, think more about drinking and consume more alcohol after being exposed to ads and marketing. But here is the irony: with so many choices thrown at them, these young drinkers switch brands freely. Maybe for different occasions; maybe because they feel like a different lifestyle that day. That old-school emphasis on product quality was far less fickle. When we are the brand, advertisers have to try harder, sparkling or flavoring dozens of different versions of booze and marketing them with fireworks and circus tricks. Anheuser-Busch InBev just bought a pickleball franchise. Bud Light has entered the metaverse.

Advertising now wallpapers the world, hijacking space and sound, and even the quiet inside our heads. It paws at us until it finds where we are vulnerable, then pounces. Yet according to documents exhibited at the National Archives, “in the early republic, Americans drank quantities we would consider astounding today.” In 1830, 7.1 gallons of alcohol a year for each person of drinking age—compared to today’s average of 2.3 gallons.

So much for influence.

Warm thanks to the St. Louis Media History Foundation. Its archives preserve more than a century of locally created print, radio, and TV, documenting the social history of the region—and the nation.

Read more by Jeannette Cooperman here.